Joyce Leung

(Research Assistant, BFoodTech)

Food colours and intense sweeteners, like all other food additives are Generally Recognised as Safe (GRAS) and if within “acceptable exposure” have no detrimental effects on our health.

Does this statement instil enough confidence regarding long-term consumption of processed foods, especially in children who are still growing and developing?

If not, we suggest reading the rest of this 2-part article.

Intense sweeteners

Intense sweeteners, also known as artificial sweeteners, are used in small quantities to replace regular refined sugar and provide a lower calorie replacement.[1]

RELATED — Artificial Sweeteners: Are they a Healthy Substitute to Sugar?

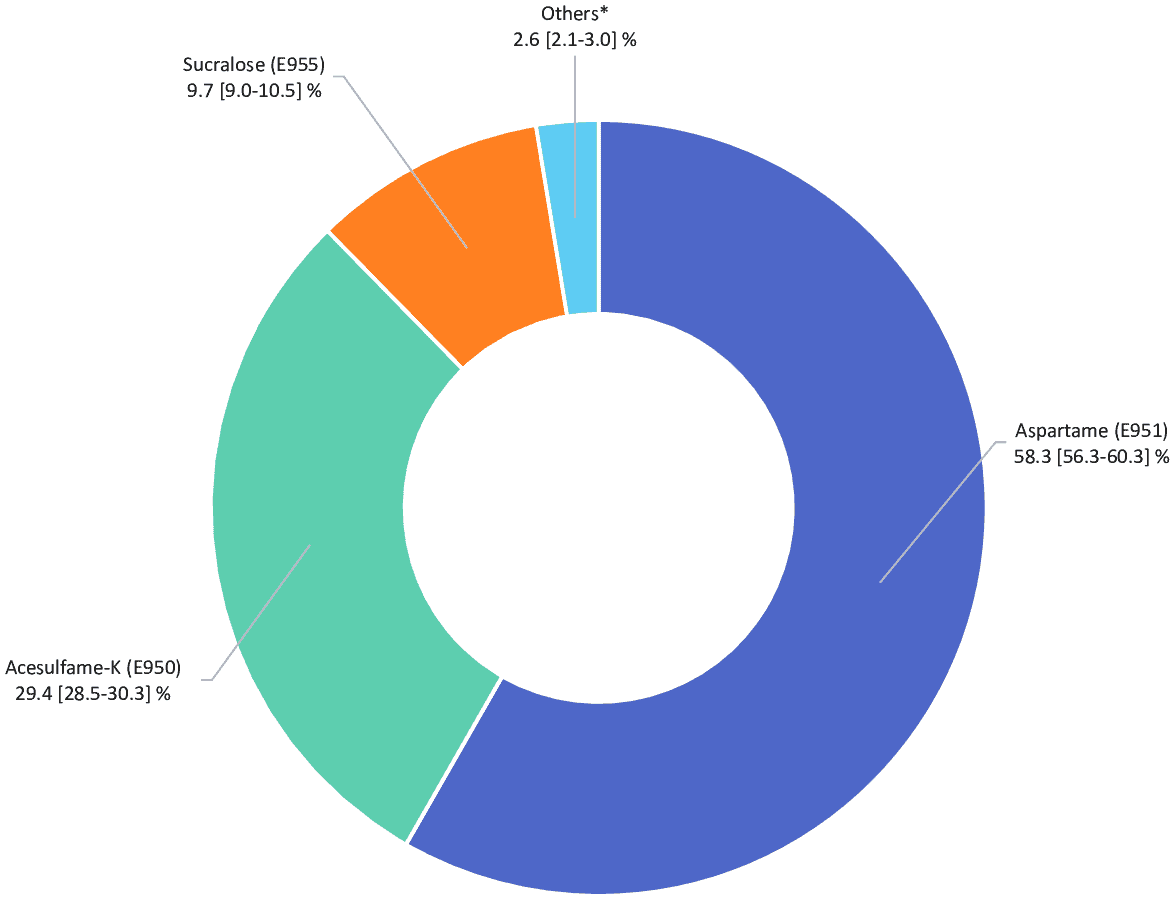

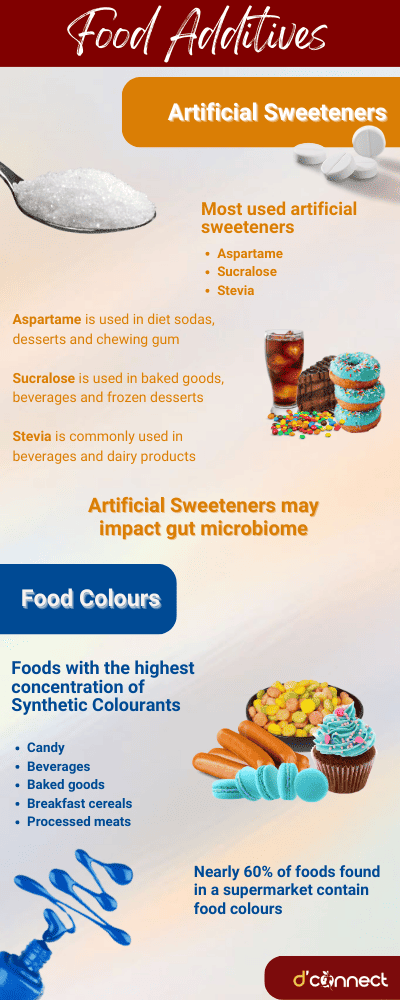

The top three intense sweeteners used in food production are aspartame, sucralose, and stevia.

Source: Debras, C. Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study. (2022)

Aspartame is commonly used in diet sodas, desserts, and chewing gum.[1]

Sucralose is often used in baked goods, beverages, and frozen desserts due to its high heat stability and long shelf life.[2]

Stevia, a natural sweetener derived from the stevia plant, is commonly used in beverages and dairy products due to its non-caloric properties and ability to enhance the flavour of the product.[3]

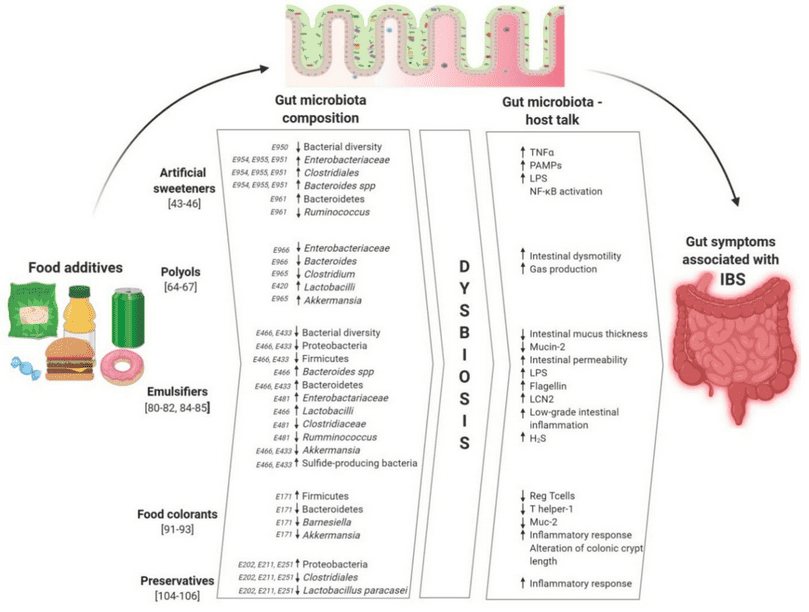

The use of artificial sweeteners has been associated with potential negative effects on human health.

Artificial sweeteners may impact gut bateria

Source: Rinninella E. Food Additives, Gut Microbiota, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Hidden Track. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. (2020)

This can potentially lead to detrimental effects on blood sugar levels in people with diabetes.[4]

RELATED — Type 1 Diabetes: Autoimmune disease that is on the rise

In addition, aspartame, a common chemical sweetener found in Equal (zero calorie sweetener), has been linked to possible side effects such as headaches, seizures, and mood changes.[5]

Stevia has also been associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer in animal studies, although this has not been confirmed in humans.[6]

Dosage and acceptable daily intake of Intense Sweeteners

The safe quantities of artificial sweeteners can vary depending on the specific type of sweetener.[6]

Artificial Sweetener – ADI (mg/kg of body weight per day)

- Aspartame – 50 mg/kg

- Saccharin – 15 mg/kg

- Sucralose – 5 mg/kg

- Steviol glycosides – 4 mg/kg

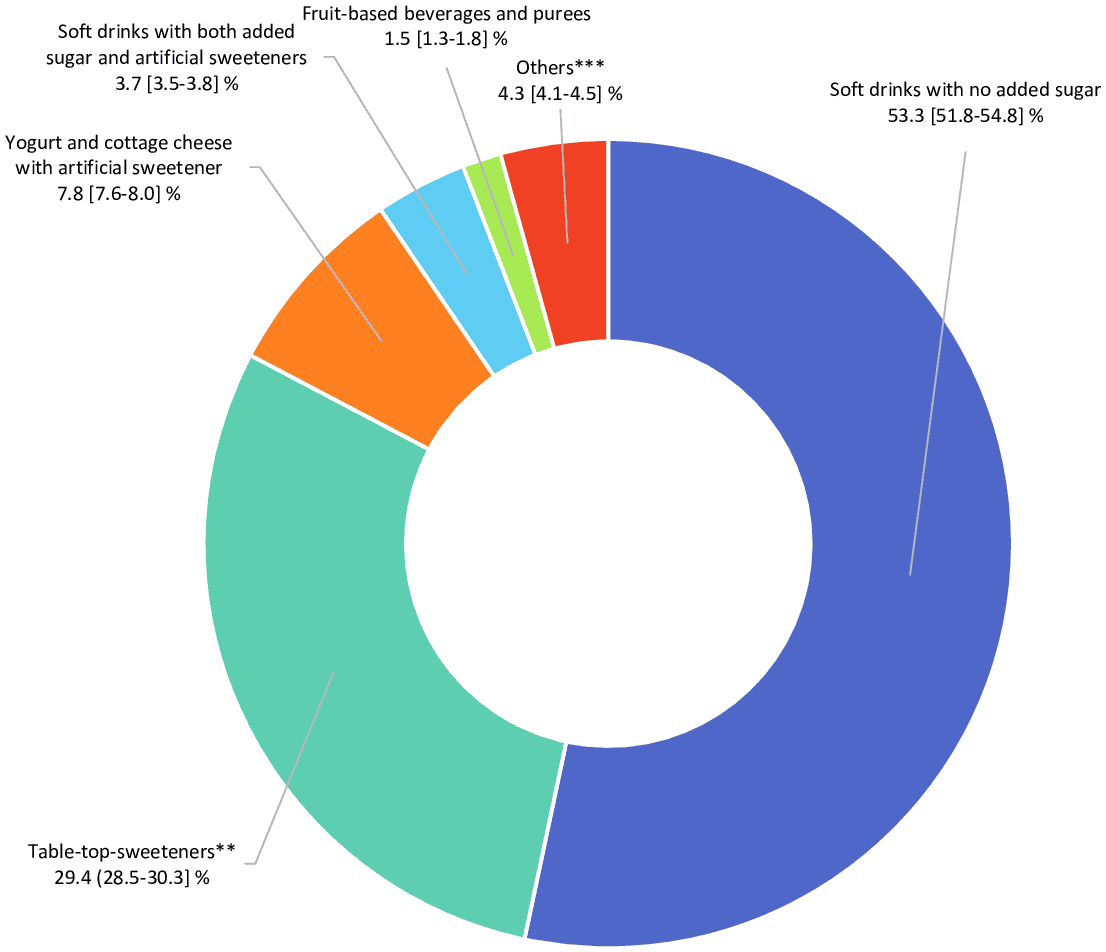

Foods with the highest concentration of Intense Sweeteners

- Soft drinks and other carbonated beverages

- Sugar-free or low-calorie flavoured waters and sports drinks

- Chewing gum and other confectionery products

- Baked goods (cakes, cookies, and pastries)

- Dairy products (yogurt and ice cream)[6]

As we can see from this image, a large majority of artificial sweeteners are placed in soft drinks and sugar-replacement sweeteners.

Food colours

Food colours can either be synthetic or naturally derived. They are used in the food industry to enhance the appearance and appeal of food products.

Like all food additives, the safety of food colours has been assessed and approved by FSANZ, EFSA, and US FDA.[6]

While both types of food colours are used in the industry, there has been a shift towards natural colours due to consumer concerns about the safety of artificial food dyes and the possible health benefits of natural pigments.[7,8]

It is important to note that synthetic food colours that have a numeric code of E have been proved to have no detrimental effects on human health at acceptable exposures.[6]

The phrase “acceptable exposure” refers to the levels of exposure to these additives that are considered safe for human consumption based on safety evaluations and risk assessments.

This, however, doesn’t tell us much when it comes to continuous and frequent consumption of processed foods, and if there’s a compounding effect of food colours, that surpasses the “acceptable exposure” limits.

Also, concerns have been raised about the impact of food colours on children’s behaviour.

The possible link between food colours and hyperactivity in children has been studied by various research teams over the years.

Source: Stevens, L. Mechanisms of behavioral, atopic, and other reactions to artificial food colors in children. (2013)

Overall, while some studies have provided strong evidence supporting a link between food colours and hyperactivity in children, others have produced inconclusive results.[9,10]

However, given the potential risks associated with these additives, many experts recommend limiting or avoiding them in the diet of children with hyperactive behaviours.

In particular, The University of Southampton conducted a study that investigated the possible link between food colours and hyperactivity in children.[11]

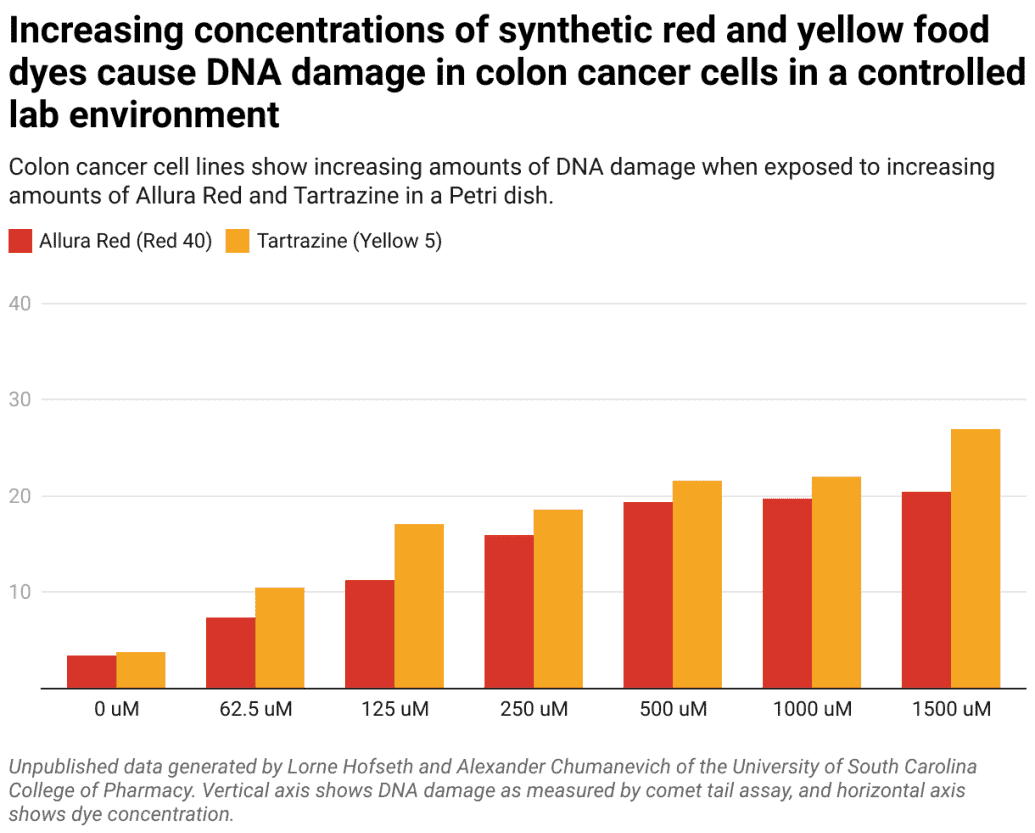

These 6 colours are:

- sunset yellow (E110)

- quinoline yellow (E104)

- carmoisine (E122)

- allura red (E129)

- tartrazine (E102)

- ponceau 4R (E124)

The study found that there may be a link between some food colours and hyperactivity in children, but further research is needed to establish a causal link.[6]

The major concern about food colours with respect to the safety of food is the lack of uniform regulations worldwide regarding the use of food colours.[12,13]

FSANZ, EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and US FDA have all conducted their own investigations on this study and did not find a causal link between consuming food colours and hyperactivity.

However, the European Union has required a warning statement be used on some food colours.[14]

The warning statement reads: “May have an adverse effect on activity and attention in children” or a similar statement to alert consumers about the potential effects of these food colours on children’s behaviour.

Dosage and acceptable daily intake of Food Colours

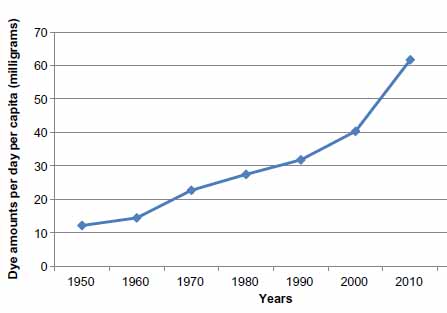

The ADI for artificial/synthetic food colours is 40mg per kilogram of body weight. To exceed these levels, a person weighing 70kg would need to consume over 4 litres of soft drinks.[15]

Considering that certain data states that close to 90% of all processed foods contain food colours, with over 55% being artificial food colours, some individuals could be surpassing the daily allowance.

Nearly 60% of foods found in a supermarket contain food colours

This could be a combination of sweet drinks, candy and sweets, different snacks and chocolate, and fast food.

Foods with the highest concentration of Synthetic Colourants

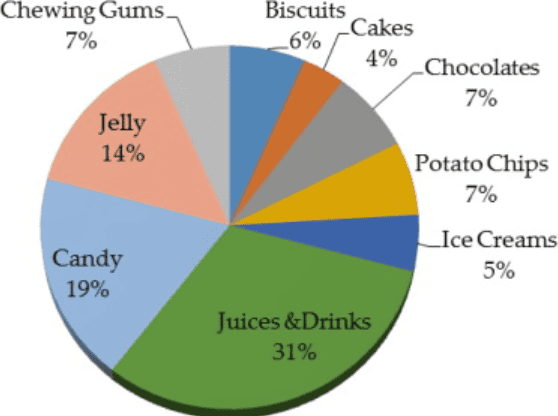

Food colours in different types of food

Source: Ahmed, M. Dietary intake of artificial food color additives containing food products by school-going children. (2021)

The alarming fact is that a large majority of processed foods have food colours added to them. That is why we should have limited amounts of processed foods such as

- candy

- beverages

- baked goods

- breakfast cereals

- processed meats

Natural food colours are commonly used in products marketed as “all-natural” or “organic”.

Summary

Note — feel free to download and share this illustration.

Related Questions

1. How many groups of food additives are there?

There are at least 20 groups of food additives categorized based on their function.

RELATED — What are Food Additives and why are they in our food?

2. What are the top 3 food additives that we should avoid?

The top 3 food additives to avoid are

- high fructose corn syrup

- artificial sweeteners

- monosodium glutamate (MSG)

3. Do food additives have any health benefits?

Some food additives like vitamins and minerals can have health benefits, but most are used to enhance the appearance, flavour, or texture of food, rather than providing health benefits.

Are there any particular (processed) foods that you are eating often, and are you now wondering about certain ingredients? Feel free to let us know in the comments, or ask any question that you may have.

If you would like to read the first part of this topic, you can find it here — 5 Most Common Food Additives in our Food (and should we avoid them)? (Part 1).

Joyce is a dedicated and passionate undergraduate with a keen interest in research and development of novel foods. She is currently completing her studies with a focus on becoming a Bachelor of Food Technology with Honors major in Food Product Technology.

Her personal passion is in finding new technologies and processing methodologies that can improve the existing products in the food market.

References

(1) Grenby, T.H. Intense sweeteners for the food industry: an overview. Trends in Food Science & Technology. (1991). Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/092422449190598D

(2) Intense Sweeteners. Food Standards Australia New Zealand. (April 2023). Retrieved from https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/additives/Sweeteners

(3) Sweeteners: Addressing Common Questions and Debunking myths. Eufic. Food facts for healthy choices. (December 2021). Retrieved from https://www.eufic.org/en/whats-in-food/article/sweeteners-addressing-common-questions-and-debunking-myths

(4) Artificial Sweeteners – What Are They and Their Effects. International Nutritional Immunology Association. (April 2021). Retrieved from https://nutritionalimmunology.org/artificial-sweeteners-what-are-they-and-their-effects/

(5) Artificial sweeteners and other sugar substitutes. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/artificial-sweeteners/art-20046936

(6) Amchova, P. Health safety issues of synthetic food colorants. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. Volume 73, Issue 3, December 2015. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0273230015300751

(7) Amaya, D. Natural food pigments and colorants. Current Opinion in Food Science. Volume 7, February 2016. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214799315001046

(8) Noor. N, Valorization of natural colors as health-promoting bioactive compounds: Phytochemical profile, extraction techniques, and pharmacological perspectives. Food Chem. 2021 Nov 15. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34091168/

(9) Food Additives Linked To Hyperactivity In Children, Study Shows. Science News. September 2007. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/09/070909202847.htm

(10) Nigg JT, Lewis K, Edinger T, Falk M. Meta-analysis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, restriction diet, and synthetic food color additives. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012 Jan;51(1):86-97.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.015. PMID: 22176942; PMCID: PMC4321798.

(11) Major study indicates a link between hyperactivity in children and certain food additives. September 2007. University of Southampton. Retrieved from https://www.southampton.ac.uk/news/2007/09/hyperactivity-in-children-and-food-additives.page#:~:text=A%20study%20by%20researchers%20at%20the%20University%20of,artificial%20food%20colours%20and%20the%20preservative%20sodium%20benzoate.

(12) Food Colours. European Food Safety Authority. Retrieved from https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/food-colours

(13) Verma, M. Food colours: the potential sources of food adulterants and their food safety concerns. Biotechnological Approaches in Food Adulterants (pp.79) Publisher: Taylor and Francis group. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342585789_Food_colours_the_potential_sources_of_food_adulterants_and_their_food_safety_concerns

(14) Food Colours. Food Standards Australia New Zealand. (February 2019). Retrieved from https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/additives/foodcolour

(15) Why synthetic colours are used in food. Ministry for Primary Industries. Retrieved from https://www.mpi.govt.nz/food-safety-home/food-additives-preservatives/synthetic-food-colours/