Farha Ramzan

Research Fellow

Almost everyone’s favourite snack is nuts, and the main reason for that is probably that we don’t feel guilty when snacking on nuts, unlike cookies or chocolate.

Nuts are a great source of protein and healthy fats, and they contain significant amounts of minerals and vitamins. But apart from tasting great, what else are they good for?

Growing evidence and research has reported that consumption of nuts reduces the incidence and risk of several diseases including cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes and different types of cancers.

Today, we will look more closely into the research on cancer and nut consumption.

Nuts - what are they?

Nuts are dry, single-seeded fruits with high oil content. Usually, they are enclosed in a leathery or solid outer shell with a protective husk.

Based on this botanical definition,

- chestnuts

- hazelnuts

- Brazil nuts

- macadamias

- pistachios

- pecans

- walnuts

are considered as true nuts.[1]

Peanuts (legumes) and almonds don’t meet the botanical definition of a true nut, but are also considered to be nuts.

Peanuts and almonds aren’t nuts

Nuts are widely consumed worldwide, and evidence shows they have been a staple in the human diet since prehistoric times.[2]

For example, a recent archaeological dig in Israel found that seven nuts, including

- wild almonds

- prickly water lily

- water chestnut

- two varieties of acorns and pistachios

formed a significant part of the human diet 780,000 years ago.[3]

In another setting, the oldest walnut discovered in Iraq dates back to 50,000 BC, further confirming the use of nuts since ancient times.[4]

Nuts are nutrient-dense foods with a wide use in healthy diets. In general, nuts are cholesterol-free, a great source of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, and a good source of proteins.

Nuts are also a great source of

- vitamin E

- vitamin K

- Vitamin B1 (Thiamine)

- Vitamin B9 (Folate)

- Magnesium (for a great night of sleep)

- Copper (Heart, Hair and Skin Health)

- Potassium (Blood pressure, heart rhythm, and PH balance)

- selenium

- fibres (soluble and insoluble)

Nuts also contain naturally occurring phytochemicals, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, tannins, stilbenes, lignans and phenolic aldehydes, with recognized benefits to human health.[1]

Potency: Organic or non-organic nuts

Although nuts have substantial nutritional benefits, how the nuts are grown could have a massive impact on these benefits.

Conventionally grown nuts or non-organic nuts are heavily sprayed using pesticides at the time of their picking and shelling. The benefits of spraying the nuts with these pesticides enable more extended shelf life and protection from pests on storage.

The high oil content in the nuts leads to increased absorption of pesticides, causing elevated chemical exposure by humans during consumption.[5]

In contrast, nuts that are grown without the use of these sprayed pesticides are termed organic nuts. The intake of organic nuts is shown to have significant health benefits, such as reduced incidence of

- Infertility

- Congenital disabilities

- Allergic sensitisation

- Metabolic syndrome

- High BMI

- Lymphomas[6]

Important note – it’s always recommended to check where your nuts, or any other food item, are originating from, and also if they are really grown in an organic way.

Nuts and research

With nuts being a valuable source of proteins, fatty acids, vitamins, folic acid, phytochemicals and fibre, it is expected that they have an important role in the reduction and prevention of risk for cancer.

Health benefits of nuts

Inflammation and oxidative stress is known to play a huge role in the development of various cancers, which makes it likely that the antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties of nuts and their components may contribute to anticancer activities.[7]

The impact of nut consumption and benefits on health outcomes have been investigated extensively, particularly due to the complex composition of bioactives present in different nuts, including

- proteins

- fibres

- minerals

- vitamins

- phytochemicals

- antioxidant

- anti-inflammatory compounds

- monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids

RELATED — Types of Fats: Healthy and Unhealthy Dietary Fats

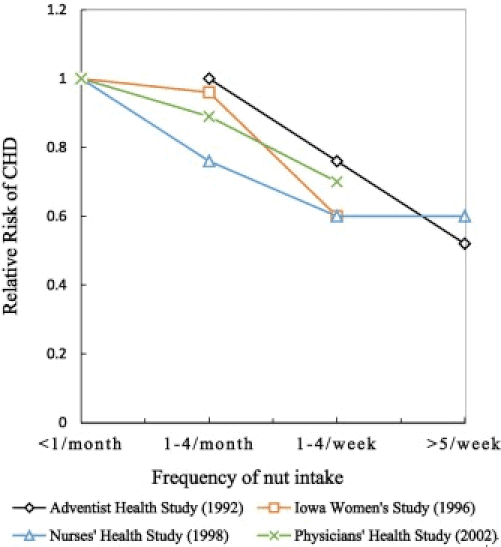

Data from large, well-conducted prospective and meta-analyses studies have suggested potent cardioprotective effects of nut consumption, with higher nut consumption to decrease 15-30% of different cardiovascular disease related mortalities.[7]

Source: Sabate, J. Nuts and Cardiovascular Disease. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases Volume 61. (2018)

Nut consumption is associated with decreased incidence of cancers and the related mortality

Nuts are also reported to have neuroprotective effects and positively impact cognitive function, depression and overall brain health.[8]

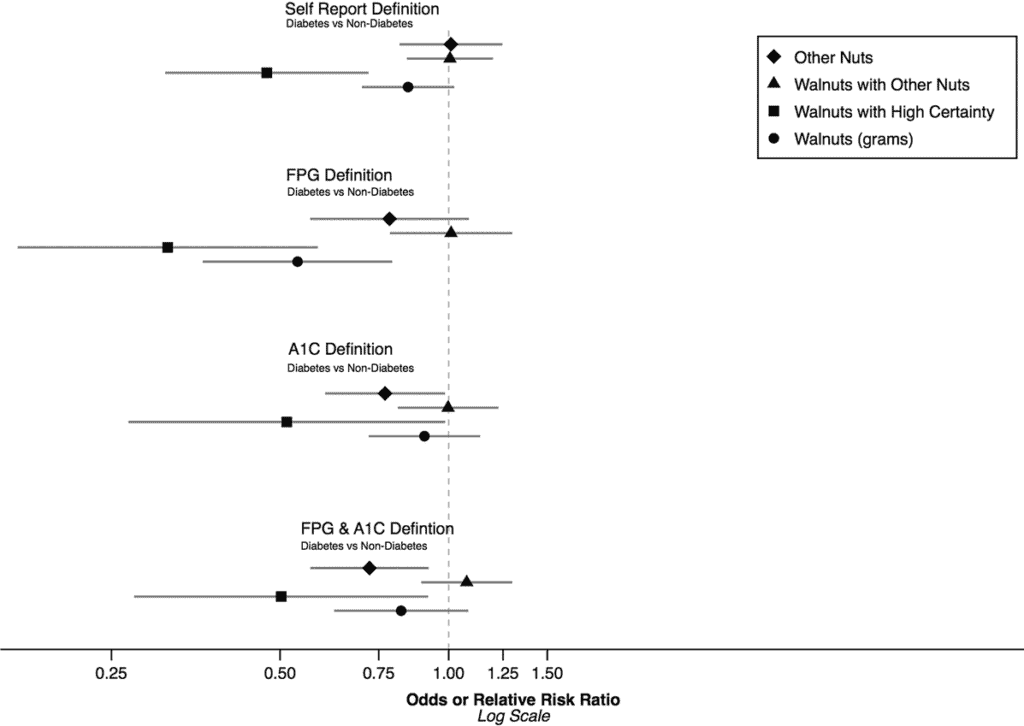

The effects of nut consumption on risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) have mostly been inconclusive, but the consumption of walnuts in particular is shown to have beneficial effects.[9]

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

In a meta-analysis conducted by the NHS, an inverse relationship was shown to exist between the consumption of walnuts and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.[9]

Source: Martin, C. Association between walnut consumption and diabetes risk in NHANES. (2018)

Also, the consumption of nuts may help in weight loss by lowering the BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, as well as fasting concentrations of apolipoprotein B and glucose.

Nuts and potential health risks

Nuts may contain increased levels of one of the most potent carcinogenic substances – the mycotoxin aflatoxin B1.

Produced by moulds, aflatoxins can be present in a range of foods, including nuts.

A study conducted in Swedish residents, increased aflatoxin B1 exposure due to increased nut consumption was shown to increase the estimated zero to three additional cases of liver cancer in the population.[10]

Source: Kooijmans, R. Aflatoxins – how a toxin causes liver cancer.

At the same time, this increased nut consumption was shown to prevent 7680 individuals from developing their first cardiovascular disease (306/100,000 person-year) and could also contribute about 55,000 saved disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for stroke and 22,000 for myocardial infarction (MI).

In this case, the health benefits of nut consumption outweigh the risks associated with aflatoxin B1 exposure. However, it is essential to take efforts for the reduced aflatoxin exposure from nuts.

Another risk and a potential health concern of nut consumption would involve allergic reaction to several nuts, including peanuts and tree nuts.

Nut allergic reactions appear to be particularly severe, sometimes even life-threatening, and can be fatal following their ingestion.

Clinically, nut allergy can be represented either as

- primary nut allergy

- pollen food syndrome (PFS)/oral allergy syndrome (OAS).[11]

Children have increased prevalence of nut allergies as compared to adults

Prevalence of nut allergies varies by geographical regions and age.

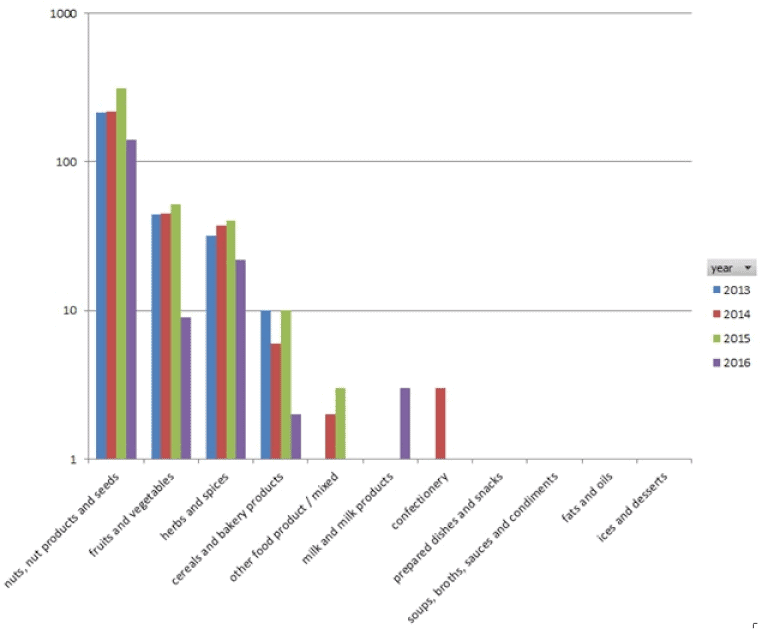

Nuts and cancer

The antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties of nuts are shown to prevent the risk and development of various cancers.

In particular, a dose response relationship between nut consumption and reduced cancer risk is shown to exist in a previously conducted meta-analysis of 29 studies.[12]

The increase in nut consumption meant a lower risk of

- colorectal cancer

- gastric cancer

- pancreatic cancer

- lung cancer

Another example would involve an observational study of 826 patients with stage III colorectal cancer, where diets involving a higher consumption of nuts was shown to be associated with a significantly reduced incidence of cancer recurrence and mortality in patients.[13]

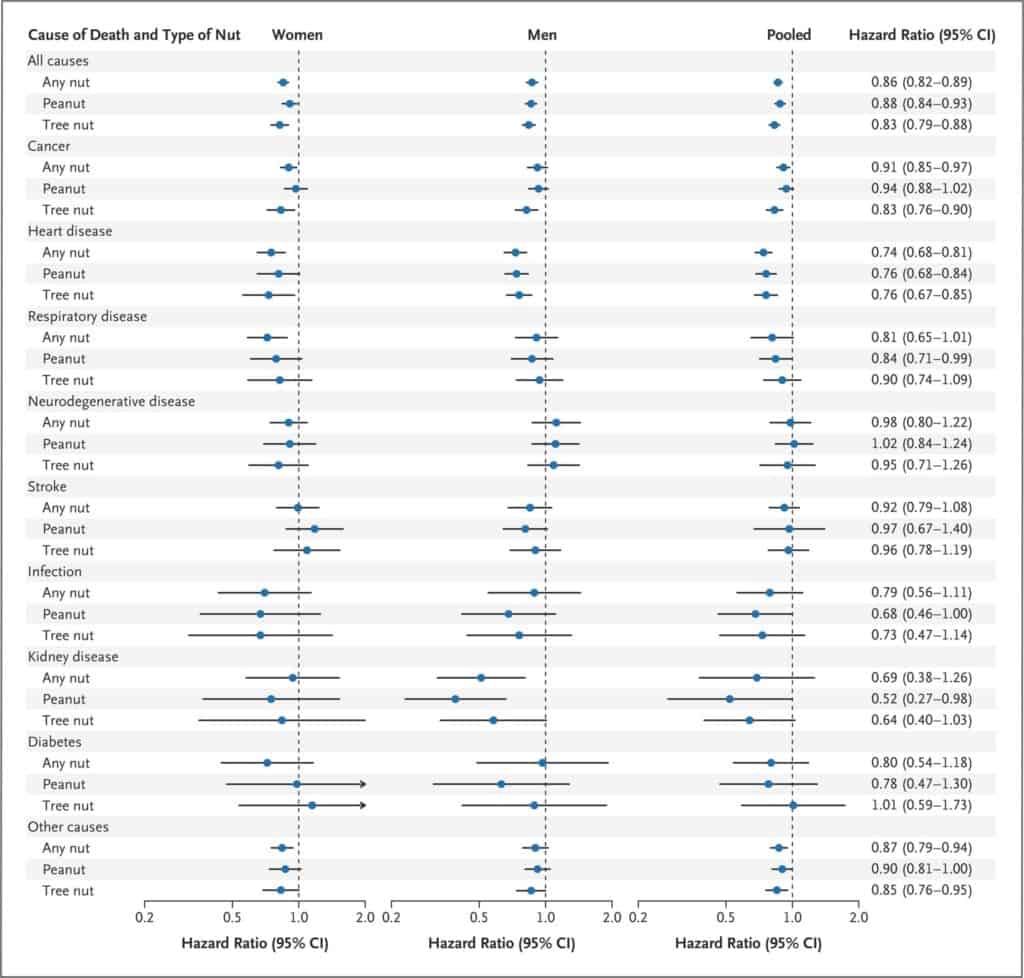

Source: Stampfer, M. Association of Nut Consumption with Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. (2013)

Researchers believe that nuts affect cancers by

- inhibition of tumour growth by blocking agents (e.g., ellagic acid, flavonoids, indole-3-carbinol)[14]

- prevention of tumour progression by suppressing agents (e.g., βcarotene and resveratrol

- changes in the gut microbiota (nut fibre fermentation by the gut microbes produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that promote gut function).[15]

The phytochemicals present in nuts add to their anticancer and antioxidant properties, but the exact mechanisms of action are still under research and debate.

Nuts in an everyday diet

With nuts being rich in unsaturated fats, vitamins, minerals, fibres and a number of phytochemicals, their regular consumption is recommended as part of a number of dietary guidelines around the world.[16]

However, the daily recommended intake of nuts differs based on different authorities.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recommends a regular consumption of 30g per day to provide health benefits.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends a daily intake of around 42.5g of nuts.

In New Zealand, the National Heart Foundation recommends a daily consumption of 30g of nuts.

30g is equivalent to a handful of nuts

Based on this recommendation, children up to 8 years old are recommended to have a 1 ½ serving of daily nuts, and older children and adolescents should have 2 ½ servings of daily nuts.

How to eat and prepare nuts

To maintain the health benefits, consuming nuts in their raw forms is highly recommended.

Consuming nuts raw enables the delivery of their bioactives particularly antioxidants and phenolics in the natural form. However, the taste and texture of raw nuts can make them less palatable by certain individuals.

That is why dry roasting and lightly salted nuts are recommended by health professionals.[17]

Roasting nuts is shown to enhance desired sensory quality along with a favourable healthy nut composition. Roasting at low/medium temperatures (120° to 140°C) has little impact on nutrient composition, except for the loss of antioxidants, particularly phenolic compounds that reside on the outer peel.

Roasting at high temperatures (above 160°C) is shown to reduce the beneficial activity of nuts by changing the bioactive profiles of acrylamide, antioxidant capacity and tocopherols.

For example, roasting pistachios at a high temperature is shown to increase their acrylamides levels, which can have carcinogenic effects in the body.[18]

Related Questions

1. What are the top three healthiest nuts to eat?

Most of the nuts offer diverse health benefits. The top three healthiest nuts would include

- Almonds (high in calcium)

- Brazil nuts (selenium-rich)

- Pecans (fibre-dense)

2. Can I eat Brazil nuts every day?

Yes, but you need to be careful not to eat too many due to their selenium content. Usually 3–5 nuts daily will satisfy your selenium needs.

3. Who should avoid eating nuts?

While nuts provide numerous health benefits, they should be avoided by people who are prone to any allergic reaction to nuts.

In our next article, Anti-cancer foods: The Healthiest Nuts (Part 2), we are looking specifically at certain types of nuts and their anticancer properties.

Farha is a Researcher at Liggins Institute, the University of Auckland. Her research interests involve understanding the complex interplay between the genetics, epigenetics and dietary patterns of an individual and how these interactions predispose an individual to develop metabolic diseases…

If you would like to learn more about Farha, see Expert: Farha Ramzan.

References

(1) Ros, E. (2010, July). Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients, 2(7), 652–682. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu2070652

(2) Eaton, S. B., & Konner, M. (1985). Paleolithic nutrition: A consideration of its nature and current implications New England Journal of Medicine, 312, 283–289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198501313120505

(3) Goren-Inbar, N., Sharon, G., Melamed, Y., & Kislev, M. (2002). Nuts, nut cracking, and pitted stones at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99(4), 2455–2460 https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.032570499

(4) Casas-Agustench, P., Salas-Huetos, A., & Salas-Salvadó, J. (2011). Mediterranean nuts: Origins, ancient medicinal benefits and symbolism. Public Health Nutrition, 14(12A), 2296–2301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011002540

(5) Rodushkin, I., Engström, E., Sörlin, D., & Baxter, D. (2008). Levels of inorganic constituents in raw nuts and seeds on the Swedish market. The Science of the Total Environment, 392(2–3), 290–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.11.024

(6) Crinnion, W. J. (2010). Organic foods contain higher levels of certain nutrients, lower levels of pesticides, and may provide health benefits for the consumer. Alternative Medicine Review: A Journal of Clinical Therapeutic, 15(1), 4–12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20359265/

(7) Ros, E., Singh, A., & O’keefe, J. H. (2021). Nuts: Natural pleiotropic nutraceuticals. Nutrients, 13(9), 3269. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093269

(8) Theodore, L. E., Kellow, N. J., Mcneil, E. A., Close, E. O., Coad, E. G., & Cardoso, B. R. (2021). Nut consumption for cognitive performance: A systematic review. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 12(3), 777–792. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33330927/

(9) Arab, L., Dhaliwal, S. K., Martin, C. J., Larios, A. D., Jackson, N. J., & Elashoff, D. (2018). Association between walnut consumption and diabetes risk in NHANES. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 34(7), e3031. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/dmrr.3031

(10) Eneroth, H., Wallin, S., Leander, K., Sommar, J. N., & Åkesson, A. (2017). Risks and benefits of increased nut consumption: Cardiovascular health benefits outweigh the burden of carcinogenic effects attributed to aflatoxin B1 exposure. Nutrients, 9(12), 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121355

(11) Tagliati, S., Barni, S., Giovannini, M., Liccioli, G., Sarti, L., Alicandro, T., … Mori, F. (2021). Nut allergy: Clinical and allergological features in Italian children. Nutrients, 13(11), 4076. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8623984/

(12) Aune, D., Keum, N. N., Giovannucci, E., Fadnes, L. T., Boffetta, P., Greenwood, D. C., … Norat, T. (2016). Nut consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer, all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMC Medicine, 14(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0730-3

(13) Fadelu, T., Zhang, S., Niedzwiecki, D., Ye, X., Saltz, L. B., Mayer, R. J., … Fuchs, C. S. (2018). Nut consumption and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: Results from CALGB 89803 (Alliance). Journal of Clinical Oncology. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2017.75.5413

(14) Hilbig, J., Policarpi, P. de B., Grinevicius, V. M. A. de S., Mota, N. S. R. S., Toaldo, I. M., Luiz, M. T. B., … Block, J. M. (2018). Aqueous extract from pecan nut [Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh) C. Koch] shell show activity against breast cancer cell line MCF-7 and Ehrlich ascites tumor in Balb-C mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 211, 256-266. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378874117318305?pes=vor

(15) Creedon, A. C., Hung, E. S., Berry, S. E., & Whelan, K. (2020). Nuts and their effect on gut microbiota, gut function and symptoms in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutrients, 12(8), 2347. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7468923/

(16) Brown, R., Gray, A. R., Chua, M. G., Ware, L., Chisholm, A., & Tey, S. L. (2021). Is a handful an effective way to guide nut recommendations? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7812. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/15/7812

(17) Schlörmann, W., Birringer, M., Böhm, V., Löber, K., Jahreis, G., Lorkowski, S., … Glei, M. (2015). Influence of roasting conditions on health-related compounds in different nuts. Food Chemistry, 180, 77-85. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308814615001867?pes=vor

(18) Asadi, S., Aalami, M., Shoeibi, S., Kashaninejad, M., Ghorbani, M., & Delavar, M. (2020). Effects of different roasting methods on formation of acrylamide in pistachio. Food Science & Nutrition, 8(6), 2875–2881. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1588