Bernadeth Atrinindarti

MAppSc (Advanced Nutrition Practice)

If you have just joined us, we suggest first having a read of The Healthiest Herbs and Spices (Part 1). If you have already done that, we can then continue by going into more detail on the differences between organic and non-organic herbs and spices.

Potency — Organic or Non-Organic herbs and spices

Organic herbs and spices are grown as nature intended. This means that they have not been:

- genetically modified

- sprayed with toxic fertilizers and pesticides

- irradiated (use of electromagnetic radiation to control the microbial population. This can cause negative effects and change the chemical composition.)

In organic systems, the use of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers is strictly prohibited. For fertilization, organic fertilizers are widely used.[1]

Spices and herbs contain numerous biologically active compounds from the group of polyphenols and carotenoids. These compounds are called natural pesticides and are used by plants against pests.[1]

A study showed that organic herbs contained higher levels of total polyphenols, flavonoids, and phenolic acid compared to non-organic herbs. This experiment showed that the total polyphenols in organic herbs are 1769.9 mg/100 g compared to conventional herbs with 1175 mg/100 g.[1]

Organic herbs contain nearly 40% more polyphenols than non-organic herbs

In organic systems, the biological activity of the soil is greater than in conventional farming thus making organic herbs have a higher level of bioactive compounds than the conventional systems.[1]

Clove

Cloves are dried flower buds derived from the clove tree.

Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) originated in Indonesia and has usually been used in cooking and traditional medicine for many years. Cloves contain a variety of bioactive components such as:

- sesquiterpenes

- eugenol (volatile oil)

- caryophyllene

- tannins

- gum

Eugenol has been known to have a dual effect, antioxidant and prooxidant, which is beneficial in both cancer prevention and treatment.[2,3]

A research study by Liu et al. found that clove extract could suppress growth and induce cell death in colon cancer cells. The mice used in the study were administered 50 mg/kg of ethyl acetate extract from cloves, which are the potential bioactive components responsible for their antitumor activity.[4]

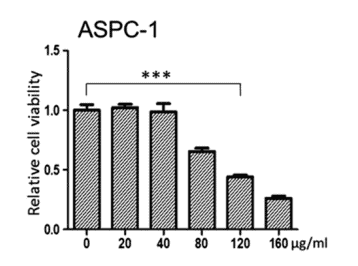

A study in human cancer cell lines showed that an aqueous extract of cloves could inhibit cancer growth significantly. Furthermore, the study confirmed that the cloves’ extract inhibits cancer cell growth in a dose-dependent manner.

Source: Lin, X. Aqueous extract of clove inhibits tumor growth by inducing autophagy through AMPK/ULK pathway. (2019)

The human pancreatic cells treated with 160 μg/ml aqueous cloves extract had a more significant effect compared to the others treated with low doses.[5]

In addition, clove may improve the ability of selected tissues to inhibit foreign compounds that might lead to the initiation of cancer cell formation.[3]

Coriander

Coriander (Coriandrum sativum), also known as cilantro or Chinese parsley, is a spice originating from the Mediterranean.

Either whole coriander leaves or dried/ground seeds are used. Coriander contains bioactive compounds such as:

- terpinene

- quercetin

- tocopherols

which are known to have anti-cancer and neuroprotective effects.

Coriander is one of the oldest recorded herbs used by humans

A few studies have been conducted to observe the effects of tocopherol in coriander in cancer cells. These studies showed that tocopherol might induce cell death and significantly suppress the growth of multiple types of cancer cells.[6]

A study by Zhang et al. indicated that the bioactive compounds from roasted coriander seeds extracts (100 μg/ml) may inhibit by 4-43% the growth of various human tumor cells including gastric carcinoma, prostate carcinoma, colon carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and lung carcinoma.[7]

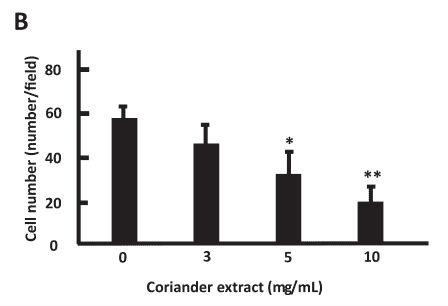

Another study in the human hepatocellular cancer cell line showed that coriander extract could inhibit cancer cells’ migration and invasion ability. See the charts below.

Source: Nakamura, T. Effects of Coriandrum sativum on Migration and Invasion Abilities of Cancer Cells. (2020)

The cancer cells were treated with 3, 5, and 10 mg/ml coriander extract and the result indicated a significant difference between the control group and the treated group.[8]

Cumin

Cumin (Cuminum cyminum) is native to Irano-Turanian region and is usually used as a food seasoning and an extract oil for perfumes.

Cumin is widely grown in India, China, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. It’s also known for its medicinal role in many countries, including Southeast Asia and Iran.

Source: Soni @ Unsplash

Thymoquinone (TQ) is the most abundant bioactive component of black cumin seed oil. Thymoquinone has been found to have

- antioxidant

- antimicrobial

- anti-inflammatory

- chemopreventive properties[3]

A few studies have indicated the ability of TQ to suppress tumor cell proliferation, including colorectal carcinoma, breast adenocarcinoma, osteosarcoma, ovarian carcinoma, myeloblastic leukemia, and pancreatic carcinoma.[3]

A study by Lang et al. showed that treatment with 375 mg/kg of TQ for 12 weeks decreased the number of large polyps in the small intestine and induced cell death of colorectal cancer in mice.[9]

Another study showed that the administration of 250 mg/kg for 5 days of black cumin seed ethanolic extract in rats could inhibit liver carcinogenesis.[10]

Dill

Dill (Anethum graveolens) is an essential oil-bearing plant grown in Eurasia and is used in many traditional medicines.

People in the Saudi Arabia region used dill seeds for the treatment of jaundice in the liver, spleen, rheumatism disorders, and other inflammatory gout diseases.

Dill seeds and leaves have been found to have a high amount of antioxidant properties including flavonoids, terpenoids, and tannins.

The essential oil in dill contains a compound called D-limonene, which is a type of monoterpene that has been shown to help prevent and treat various types of cancer.

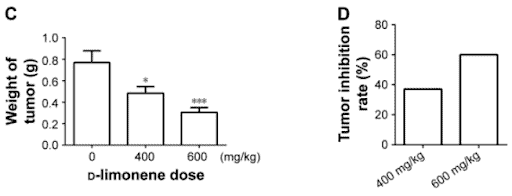

A study by Yu et al. showed that d-limonene (400 or 600 mg/kg) helped inhibit the growth of lung cancer cells and suppressed the growth of transplanted tumors in mice after 4 weeks of treatment.[11]

Source: Wang, Y. d-limonene exhibits antitumor activity by inducing autophagy and apoptosis in lung cancer. (2018)

Another study by Mohammed et al. observed the effect of the ethyl acetate fraction of dill seeds (EAFD) on human hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

The cells were treated with different concentrations (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 mg/ml) of EAFD. After 24 h of treatment, results showed a significant increase in inhibition of cancer cell growth.[12]

Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi)

Ganoderma lucidum (Fr.) Karst has been widely known as medicinal fungi in China, Korea, and Japan for centuries.

These fungi are known to maintain human vitality and promote longevity.

Source: Freepik

The edible mushroom also has been used to treat various human diseases, including allergy, arthritis, hypertension, inflammation, and cancer.

RELATED — The health benefits of mushrooms and fungi

A study by Feng et al. observed the inhibitory effect of triterpenes of G. lucidum on tumor weight in tumor-bearing mice. The tumor-bearing mice were given 30, 60 and 120 mg/kg of triterpenes of G. lucidum and showed significantly inhibited tumor weights by 38-63%.[13]

Barbieri et al. observed the effect of Ganoderma lucidum extracts in melanoma and triple-negative human breast cancer cell lines. The study showed significant inhibition of cancer cell migration at 250 μg/ml G. lucidum extracts.[14]

RELATED — How common is Breast Cancer and what are the Risk Factors?

Ginger

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) is a well-known spice that has been used in many Asian countries.

India and China have used ginger as medicine since ancient times. It is known to help reduce nausea and help the gastrointestinal system.[15]

Furthermore, ginger is also used to help with various issues such as morning sickness, colic, upset stomach, gas, bloating, heartburn, loss of appetite, and diarrhea.[15]

Ginger is a part of the same family as Turmeric

Some phenolic substances present in ginger are known to have anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties and exert substantial anti-carcinogenic and anti-mutagenic activities.

Ginger contains active compounds including:

- gingerol

- paradol

- shogoal

These compounds have anti-cancer properties and help inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines called TNF-α that have been associated with tumor promotion.

A study by Habib et al. reported that 100 mg/kg ginger extract treatment in rats with liver cancer significantly suppressed the production of TNF-α and NFκB, which could promote the initial formation of tumors in the body.[16]

A study by Karna et al. showed that 100 mg/kg of ginger extract could inhibit the growth and progression of human prostate cancer cell lines by 56%.[17]

Source: Karna, P. Benefits of whole ginger extract in prostate cancer. (2011)

A study by Lee et al. showed that colon cancer cell lines treated with 150 and 200 μM of 6-gingerol reduced the cancer cell growth rate by 22% and 28%.[18]

Another study also observed the effect of 6-gingerol in human breast cancer cells. The study showed that treatment with 6-gingerol (2.5, 5, and 10 μM) has a significant effect on the decrease of cancer cell migration.[19]

Green Tea

Green tea is derived from the plant Camellia sinensis, which is consumed in different varieties including white, green, black, or Oolong tea.

Among all those teas, green tea has been known to have the most significant health benefits on human health. The process of making green tea preserves natural polyphenols, which have health-promoting properties.

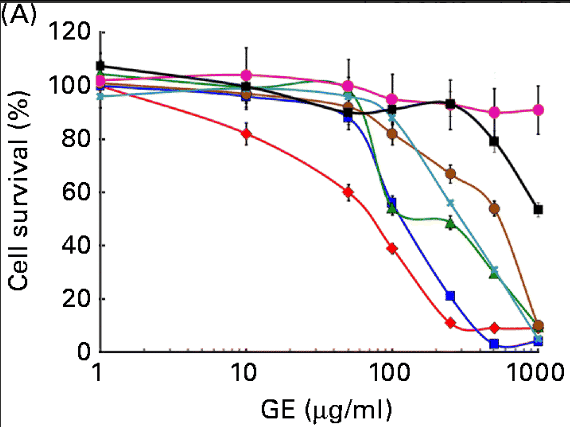

Green tea polyphenols are known to help inhibit cell proliferation and viability and exert a powerful antioxidant activity.[20]

Several studies have been conducted to explain a possible cancer-preventive activity of catechins, including:

- counteraction of tumor growth

- invasion, metastasis, and cell transformation

- inhibiting the interaction of tumor promoters and hormones[20]

Green tea may protect the brain against aging diseases

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is the major component of green tea polyphenols, which is known for its anti-cancer effects.

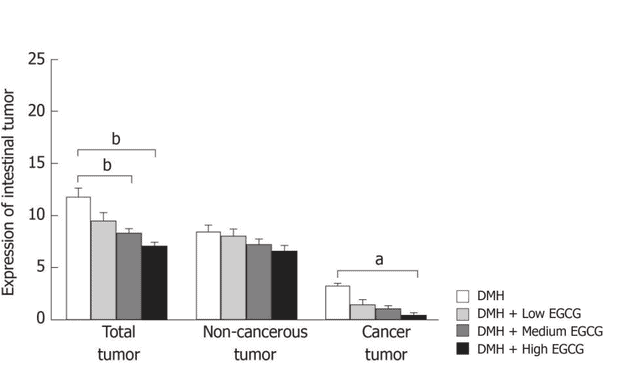

A study by Wang et al. found that after eight weeks of EGCG daily treatment (50, 100, or 200 mg/kg) in rats with colorectal cancer, there is a significantly reduced:

- tumor formation rate

- total number of tumors

- cancerous and non-cancerous tumors

- tumor volume[21]

Source: Wang, Y. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits dimethylhydrazine-induced colorectal cancer in rats. (2020)

In human studies, cancer cells treated with different quantities of EGCG resulted in shrinkage and growth inhibition of urinary bladder carcinoma cells as they were monitored for 24, 48, and 72 h.[22]

Another study observed the effect of daily treatment consisting of three green tea catechins (GTCs) capsules (200 mg each capsule, total 600 mg/day) in men with high-risk of developing prostate cancer.

RELATED — Prostate Cancer: All you need to know and are afraid to ask

Only one tumor was diagnosed among the 30 GTCs-treated men compared to nine found among the placebo-treated group.[23]

Licorice

Licorice (Glycyrrhiza) is a plant that is cultivated in countries such as China, Russia, Spain, Persia, and India.

Licorice extract is used in traditional and herbal medicine for cough and stomach problems.

Bioactive compounds of licorice including glycyrrhizin and its derivatives glycyrrhizic acid are known to have great potential as anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory agents. Furthermore, licorice polyphenols also indicate to help induce apoptosis in cancer cells.[24]

A study that focused on licochalcone A (LicA), a major phenolic component of licorice with antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory properties, showed a significant reduction in tumor formation in mice with colorectal cancer.[25]

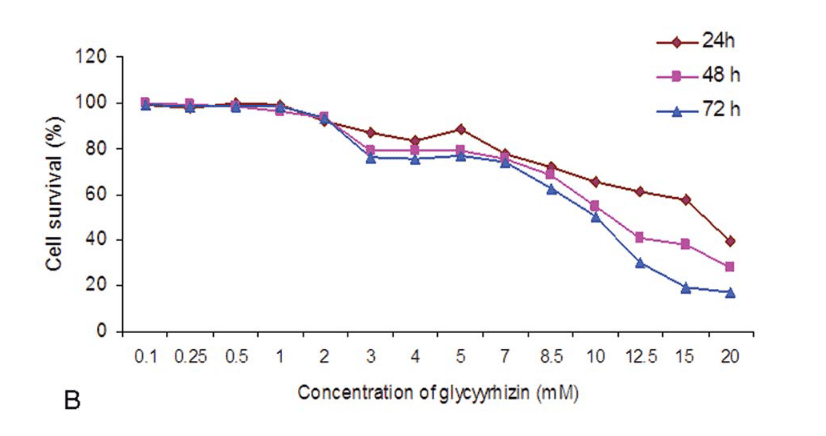

A study found that glycyrrhizin inhibits human prostate cancer cell formation. The cancer cells were treated with a high concentration of glycyrrhizin (5-20 µM) for 48 and 72 h.[26]

Source: Thirugnanam, S. Glycyrrhizin induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines DU-145 and LNCaP. (2008)

An additional study showed that concentrations of 50 and 100 mg/ml from full extracts of licorice root significantly increase cell death in colon cancer cell lines.[27]

Oldenlandia diffusa

Oldenlandia diffusa is a Chinese herbal medicine that has been used to treat various types of conditions such as:

- autoimmune diseases

- rheumatism

- arthritis

- appendicitis

In a mice study, a raw herb of Oldenlandia diffusa extract was given to mice with lung cancer at the dose of 5 g/kg. Results showed that oral administration of the herbal extract significantly reduced cancer cell growth.[28]

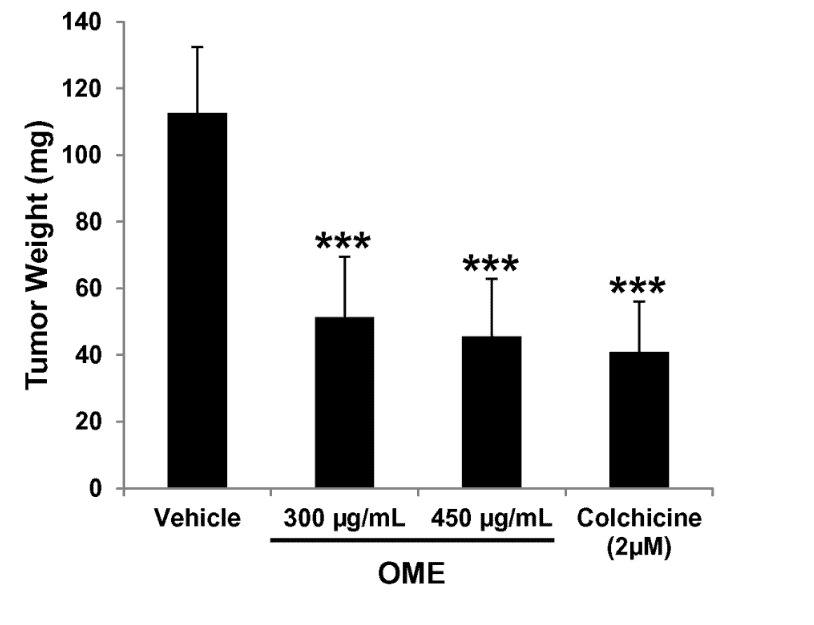

A study done on rats recorded a significant reduction in tumor number and size compared to the control group. The treated group of rats were administered 100 mg/kg or 200 mg/kg of Oldenlandia diffusa.[29]

Human studies observed the efficacy of Oldenlandia diffusa on breast cancer cells, which showed significant inhibition in cell growth and induced cell death in breast cancer cells.[30]

Another human study found that Oldenlandia diffusa extracts (ODE) at 25-200 μg/mL increased the death of colorectal cancer cells and prevented further formation of colorectal cancer lines.[31]

Oregano

Oregano (Origanum vulgare) is a herb native to the Mediterranean region that is rich in phenolic compounds and monoterpenoids.

It also has high antioxidant properties and antimicrobial activity.[32]

A study on chick embryos confirmed the anticancer activities of oregano where there was a significant reduction in tumor growth compared to the control group. Furthermore, oregano reduced tumor growth by 55 and 60% respectively.[33]

Source: Attoub, S. Anti-Metastatic and Anti-Tumor Growth Effects of Origanum majorana on Highly Metastatic Human Breast Cancer Cells: Inhibition of NFκB Signaling and Reduction of Nitric Oxide Production. (2013)

In human studies, oregano essential oil-based nanoemulsion (OENE) at 13.82 µg/mL significantly induced cell death by inhibiting cell growth causing cell shrinkage, cell density, and cell shape reduction on prostate cancer cell lines.[34]

There are 36 varieties of oregano

Another study observed the effect of Mexican oregano extract on cell formation in the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line. The study found that after treatment at 200, 300, and 400 μg/mL of Mexican oregano for 48 hr there was a decrease in cell formation by 33-67%.

Interesting fact about Mexican oregano is that it has higher concentrations of total phenolics compared to Mediterranean oregano.[35]

Related Questions

1. What nutrients do cancer patients need?

Cancer patients should eat a variety of foods that include:

- Plant-based proteins such as beans, legumes, nuts and seeds, or lean animal proteins (chicken or fish)

- Healthy fats such as monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats (e.g. avocados, olive oil, grape seed oil and walnuts)

- RELATED — Types of Fats: Healthy and Unhealthy Dietary Fats

- Carbohydrates that are minimally processed such as whole wheat, bran, and oats

- Antioxidants that include vitamins A, C, and E, selenium and zinc, and certain enzymes that absorb and attach to free radicals.

- RELATED — Vitamin C (Immunity and Collagen booster)

Phytonutrients such as carotenoids, lycopene, resveratrol, and phytosterols are also known to have health-protecting properties.

2. What foods should you avoid if you have breast cancer?

It is best to stay away from processed and highly refined foods. Also, fried foods that contain hydrogenated oils which might increase inflammation.

RELATED — Health Risks: Trans and Saturated Fats

Important to mention is that cancer patients should also avoid foods that have a higher risk of foodborne illnesses such as:

- raw fish

- raw or soft-cooked egg

- unpasteurized cheese

- unwashed fruits and vegetables.

3. Does the keto diet starve cancer cells?

Cancer cells feed off carbohydrates or blood glucose in order to multiply and grow. Therefore, the ketogenic diet might starve the cancer cells of fuel.

If you are interested in other anti-cancer foods, apart from herbs and spices, we suggest starting your “journey” with Anti-cancer foods: The Healthiest Nuts (Part 1).

Bernadeth’s passion in cooking, food and health led her to learn more about nutrition and the importance of functional foods. Throughout the years, she gained special interest in sports and performance nutrition, and the varieties of diets around the world. As a nutritionist, Bernadeth’s goal is to encourage a healthy-balanced diet and share the evidence-based nutrition knowledge in order for people to live healthier and longer lives.

Bernadeth is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect.

References

(1) Hallmann, E., & Sabała, P. (2020). Organic and Conventional Herbs Quality Reflected by Their Antioxidant Compounds Concentration. Applied Sciences, 10(10), 3468. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/app10103468

(2) Talib, W. H., AlHur, M. J., Al.Naimat, S., Ahmad, R. E., Al-Yasari, A. H., Al-Dalaeen, A., Mahmod, A. I. (2022). Anticancer Effect of Spices Used in Mediterranean Diet: Preventive and Therapeutic Potentials. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.905658

(3) Kaefer CM, Milner JA. Herbs and Spices in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. (2011) Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. 2nd edition. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. Chapter 17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92774/

(4) Liu, H., Schmitz, J. C., Wei, J., Cao, S., Beumer, J. H., Strychor, S., Cheng, L., Liu, M., Wang, C., Wu, N., Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., Liao, J., Chu, E., & Lin, X. (2014). Clove extract inhibits tumor growth and promotes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Oncology research, 21(5), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.3727/096504014X13946388748910

(5) Li, C., Xu, H., Chen, X., Chen, J., Li, X., Qiao, G., Lin, X. (2019). Aqueous extract of clove inhibits tumor growth by inducing autophagy through AMPK/ULK pathway. Phytotherapy Research, 33(7), 1794-1804. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6367

(6) Das Gupta, S., & Suh, N. (2016). Tocopherols in cancer: An update. Molecular nutrition & food research, 60(6), 1354–1363. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201500847

(7) Zhang, C.-R., Dissanayake, A. A., Kevseroğlu, K., & Nair, M. G. (2015). Evaluation of coriander spice as a functional food by using in vitro bioassays. Food Chemistry, 167, 24-29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.120

(8) Huang, H., Nakamura, T., Yasuzawa, T., & Ueshima, S. (2020). Effects of Coriandrum sativum on Migration and Invasion Abilities of Cancer Cells. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology, 66(5), 468–477. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.66.468

(9) Lang, M., Borgmann, M., Oberhuber, G. et al. (2013). Thymoquinone attenuates tumor growth in ApcMin mice by interference with Wnt-signaling. Mol Cancer 12, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-12-41

(10) Fathy, M., & Nikaido, T. (2018). In vivo attenuation of angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by Nigella sativa. Turkish journal of medical sciences, 48(1), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-1701-86

(11) Yu, X., Lin, H., Wang, Y., Lv, W., Zhang, S., Qian, Y., Deng, X., Feng, N., Yu, H., & Qian, B. (2018). d-limonene exhibits antitumor activity by inducing autophagy and apoptosis in lung cancer. OncoTargets and therapy, 11, 1833–1847. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S155716

(12) Mohammed, F. A., Elkady, A. I., Syed, F. Q., Mirza, M. B., Hakeem, K. R., & Alkarim, S. (2018). Anethum graveolens (dill) – A medicinal herb induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 cell line. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 219, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2018.03.008

(13) Cao, Y., Xu, X., Liu, S., Huang, L., & Gu, J. (2018). Ganoderma: A Cancer Immunotherapy Review. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.01217

(14) Barbieri, A., Quagliariello, V., Del Vecchio, V., Falco, M., Luciano, A., Amruthraj, N. J., Nasti, G., Ottaiano, A., Berretta, M., Iaffaioli, R. V., & Arra, C. (2017). Anticancer and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Ganoderma lucidum Extract Effects on Melanoma and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Treatment. Nutrients, 9(3), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9030210

(15) Prasad, S., & Tyagi, A. K. (2015). Ginger and its constituents: role in prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2015, 142979. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/142979

(16) Habib, S. H., Makpol, S., Abdul Hamid, N. A., Das, S., Ngah, W. Z., & Yusof, Y. A. (2008). Ginger extract (Zingiber officinale) has anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory effects on ethionine-induced hepatoma rats. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil), 63(6), 807–813. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1807-59322008000600017

(17) Karna, P., Chagani, S., Gundala, S., Rida, P., Asif, G., Sharma, V., Aneja, R. (2012). Benefits of whole ginger extract in prostate cancer. British Journal of Nutrition, 107(4), 473-484. doi:10.1017/S0007114511003308

(18) Lee, S. H., Cekanova, M., & Baek, S. J. (2008). Multiple mechanisms are involved in 6-gingerol-induced cell growth arrest and apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells. Molecular carcinogenesis, 47(3), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.20374

(19) Lee, H. S., Seo, E. Y., Kang, N. E., & Kim, W. K. (2008). [6]-Gingerol inhibits metastasis of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 19(5), 313-319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.05.008

(20) Filippini, T., Malavolti, M., Borrelli, F., Izzo, A. A., Fairweather-Tait, S. J., Horneber, M., & Vinceti, M. (2020). Green tea (Camellia sinensis) for the prevention of cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 3(3), CD005004. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005004.pub3

(21) Wang, Y., Jin, H. Y., Fang, M. Z., Wang, X. F., Chen, H., Huang, S. L., Kong, D. S., Li, M., Zhang, X., Sun, Y., & Wang, S. M. (2020). Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits dimethylhydrazine-induced colorectal cancer in rats. World journal of gastroenterology, 26(17), 2064–2081. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i17.2064

(22) Chen, N. G., Lu, C. C., Lin, Y. H., Shen, W. C., Lai, C. H., Ho, Y. J., Chung, J. G., Lin, T. H., Lin, Y. C., & Yang, J. S. (2011). Proteomic approaches to study epigallocatechin gallate-provoked apoptosis of TSGH-8301 human urinary bladder carcinoma cells: roles of AKT and heat shock protein 27-modulated intrinsic apoptotic pathways. Oncology reports, 26(4), 939–947. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2011.1377

(23) Bettuzzi, S., Brausi, M., Rizzi, F., Castagnetti, G., Peracchia, G., & Corti, A. (2006). Chemoprevention of Human Prostate Cancer by Oral Administration of Green Tea Catechins in Volunteers with High-Grade Prostate Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Preliminary Report from a One-Year Proof-of-Principle Study. Cancer Research, 66(2), 1234-1240. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.Can-05-1145

(24) Wang, Z. Y., & Nixon, D. W. (2001). Licorice and cancer. Nutrition and cancer, 39(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327914nc391_1

(25) Kim, JK., Shin, E.K., Park, J.H. et al. (2010). Antitumor and antimetastatic effects of licochalcone A in mouse models. J Mol Med 88, 829–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-010-0625-2

(26) Thirugnanam, S., Xu, L., Ramaswamy, K., & Gnanasekar, M. (2008). Glycyrrhizin induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines DU-145 and LNCaP. Oncology Reports, 20, 1387-1392. https://doi.org/10.3892/or_00000157

(27) Soheila Khazraei-Moradian, Mazdak Ganjalikhani-Hakemi, Alireza Andalib, Reza Yazdani, Javad Arasteh & Gholam Ali Kardar. (2017). The Effect of Licorice Protein Fractions on Proliferation and Apoptosis of Gastrointestinal Cancer Cell Lines, Nutrition and Cancer, 69:2, 330-339, DOI: 10.1080/01635581.2017.1263347

(28) Gupta, S., Zhang, D., Yi, J., & Shao, J. (2004). Anticancer activities of Oldenlandia diffusa. Journal of herbal pharmacotherapy, 4(1), 21–33.

(29) Sunwoo, Y. Y., Lee, J. H., Jung, H. Y., Jung, Y. J., Park, M. S., Chung, Y. A., Maeng, L. S., Han, Y. M., Shin, H. S., Lee, J., & Park, S. I. (2015). Oldenlandia diffusa Promotes Antiproliferative and Apoptotic Effects in a Rat Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Liver Cirrhosis. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2015, 501508. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/501508

(30) Gu, G., Barone, I., Gelsomino, L., Giordano, C., Bonofiglio, D., Statti, G., Menichini, F., Catalano, S. and Andò, S. (2012), Oldenlandia diffusa extracts exert antiproliferative and apoptotic effects on human breast cancer cells through ERα/Sp1-mediated p53 activation. J. Cell. Physiol., 227: 3363-3372. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.24035

(31) Lu, P. H., Chen, M. B., Ji, C., Li, W. T., Wei, M. X., & Wu, M. H. (2016). Aqueous Oldenlandia diffusa extracts inhibits colorectal cancer cells via activating AMP-activated protein kinase signalings. Oncotarget, 7(29), 45889–45900. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.9969

(32) Kubatka, P., Kello, M., Kajo, K., Kruzliak, P., Výbohová, D., Mojžiš, J., Adamkov, M., Fialová, S., Veizerová, L., Zulli, A., Péč, M., Statelová, D., Grančai, D., & Büsselberg, D. (2017). Oregano demonstrates distinct tumour-suppressive effects in the breast carcinoma model. European journal of nutrition, 56(3), 1303–1316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-016-1181-5

(33) Al Dhaheri Y, Attoub S, Arafat K, AbuQamar S, Viallet J, et al. (2013) Anti-Metastatic and Anti-Tumor Growth Effects of Origanum majorana on Highly Metastatic Human Breast Cancer Cells: Inhibition of NFκB Signaling and Reduction of Nitric Oxide Production. PLOS ONE 8(7): e68808. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068808

(34) Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E., Picos-Salas, M., Leyva-López, N., Criollo-Mendoza, M., Vazquez-Olivo, G., & Heredia, J. (2017). Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids from Oregano: Occurrence, Biological Activity and Health Benefits. Plants, 7(1), 2. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/plants7010002

(35) Lee, S.-O., Ward, P. and Brownmiller, C.R. (2017), Effect of Mexican Oregano on Colon Cancer Cells. The FASEB Journal, 31: 793.13-793.13.