Michaela Dvorakova

(MFood Tech, R&D Specialist)

More often than not, we read that something that was considered safe for decades is no longer advisable for human consumption, or it’s even banned.

Even the food additives that are approved for human consumption are recommended to be consumed in limited quantities.

What should then be done with GRAS substances, where food companies can introduce new ingredients/substances without undergoing safety assessments or approval from the regulatory bodies?

Should we continue to eat such foods? How can we differentiate on the ingredients list approved food additives for those that are GRAS?

What does GRAS mean?

GRAS is an acronym for “Generally Recognised as Safe”. It’s a United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) designation that a chemical or substance added to food is considered as safe by experts under the specific conditions.[1]

Basically, it’s a system for review and approval of the ingredients for addition to food.

History behind GRAS

Food and drug laws have existed at least since The Code of Hammurabi, dating back to around 1755 BCE.

However, the real breakthrough in food and drug law came with the publication The Jungle by Upton Sinclar in 1906, where he exposed abuses in the Chicago meat-packing industry.[2]

Upton Sinclar worked undercover in the meat-packing industry for seven weeks, gathering information. In his novel he described the dangerous, unsanitary practices of slaughterhouses and meat packers.

This publication convinced Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act (also known as the “Act” or “Statute”) and the Meat Inspection Act, both signed into law in 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt.

These acts defined food and were primarily focused on adulteration, misrepresentation or sale of otherwise unfit products. Before this Act, there was nothing that could be done to the food that was illegal, because there were no food safety laws.

For example, we can find cases such as brick dust sold as cinnamon and tinted corn syrup marketed as honey. In the 1850s, food and milk tainted with formaldehyde caused deaths of 8000 American infants a year. This is known as a Swill milk scandal.[3]

Formaldehyde was used to cover swill milk, which was the tainted result of miasmic dairy cows being fed leftover mash from Manhattan and Brooklyn whiskey distilleries.[3]

The act laid the foundation for the first consumer protection agency in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration, established in 1927.

The laws were periodically updated, but another big change happened in 1938, due to a tragedy called “Elixir of Sulfanilamide”.

The Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster of 1937 was one of the most consequential mass poisonings of the 20th century.[4]

Sulfanilamide is an antibacterial drug, which was being used safely for treatment of streptococcal infections. However, liquid form was required. A new formula with raspberry flavour was prepared with 70 % diethylene glycol.

Its usage can be fatal and since the company did not carry out any toxical studies, soon after its appearance on the market resulted in the death of 105 patients. From that incident, pre-marketing approval of efficacy and safety of drugs was highly demanded.

In 1954, and again in 1958, incidents involving the safety of food forced Congress to act. Chairman James J. Delaney examined 840 food additives and only 420 were considered safe.

The Congress responded with the concept of GRAS. Concept was written into the 1958 Amendment to the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act. They set up new definitions and standards for food additives, created an entirely new class of substances and established a process of approving new substances used for food.

In the 1950s, a series of laws addressing pesticide residues (1954), food additives (1958), and color additives (1960) gave the FDA much tighter control over the growing list of chemicals entering the food supply.

In the 1960s and 1970s the medical device industry grew extensively. In 1977 Bioresearch Monitoring Programme was introduced. This programme focused on preclinical studies on animals and clinical investigations.

In 1962, drug safety was improved. For the first time, drug manufacturers were required to prove effectiveness of their products before marketing them.

In 1990, the Congress passed the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, which completely reformulated the way food product labels convey basic nutritional information. During the past decade, several laws were passed that focus on clarifying the nutritional and safety information on food labels, including the listing of trans fats and allergens.

The agency has also launched initiatives to increase public awareness of the adverse effects of tobacco products.

Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Database

The SCOGS database allows access to opinions and conclusions from 115 SCOGS reports published between 1972-1980 on the safety of over 370 Generally Recognised as Safe (GRAS) food substances. While there isn’t a direct modern equivalent to SCOGS, the FDA continues to evaluate the safety of food ingredients.[5]

The FDA established SCOGS to review safety of GRAS substances in response to a directive from President Nixon.

During the 1960s new scientific information doubted safety of cyclamate salts, substances previously considered as GRAS. As a conclusion, president Nixon asked the FDA to re-evaluate all of GRAS substances.

GRAS, food additives and approval procedure

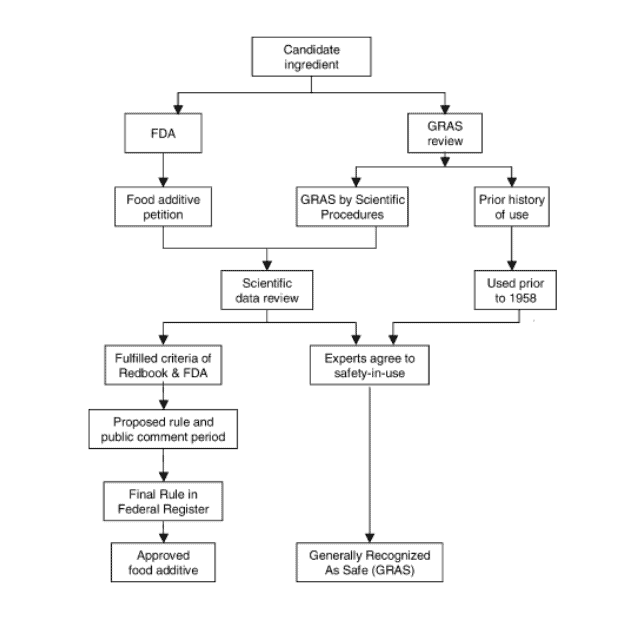

The diagram of the approval process, as shared below, shows us how substances may either enter the route as a candidate for food additive or GRAS substance.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) review

The process is initiated by a Food additive petition. It goes through scientific data review, where only animal testing data are required.

GRAS substances are only tested on animals

For food additives, human testing data are not generally required. Once the substance meets the criteria of acceptance by the FDA (criterias are described in Red Book), a proposed rule is published in the Federal Register, followed by Final Rule and incorporation into the Code of Federal Regulations.

Red Book is a guidance document issued by the FDA and it provides essential information about assessing safety of food additives, colours and substances that are GRAS.

GRAS review

The difference between the FDA approach and the GRAS review is basically just the process.

According to the FDA “…a GRAS substance is neither more safe nor less safe than an approved food additive. Rather, the distinction between a GRAS substance and an approved food additive is that, for a GRAS substance, there is common knowledge of safety within the expert community (Federal Register 62:18937–18964, 1997).”

GRAS petition is submitted to a group of experts to review scientific data to determine eligibility and safety of use, based on scientific procedures or prior use in history.

Because GRAS status may be either affirmed by the FDA or determined independently by qualified experts, FDA’s regulations do not include all GRAS ingredients and the specific uses described in the GRAS regulations may not be comprehensive for the listed ingredients.

New Zealand and GRAS

In New Zealand, the GRAS concept is not explicitly employed as it is in the United States.

In New Zealand, food additives receive approval from Food Standards Australia and New Zealand (FSANZ). Before any food additive can be used, it undergoes a safety assessment process conducted by FSANZ.[6]

RELATED — Food additives: Banned worldwide, but permitted in New Zealand

Additionally, any new additive must obtain approval from government ministers before being used as a food ingredient.

If a New Zealand company wants to sell their products in the USA, they have to receive the FDA approval.

Synlait is the second company in the world to receive a GRAS notice to use lactoferrin in infant formula and toddler formula.

What are the issues with GRAS?

The GRAS designation permits food companies to introduce new ingredients without notifying the FDA or undergoing thorough safety assessments, resulting in a lack of transparency.

Also food companies retain the authority to determine which ingredients meet the GRAS criteria and certain substances labeled as GRAS have concerns due to potential carcinogenic properties.

The most worrying aspect is the inclusion of unknown ingredients that have never been publicly evaluated.

GRAS and animal studies

Media reports occasionally link additives to cancer in animals. However, what affects animals doesn’t always apply to humans due to different biological responses.

For instance, chocolate is toxic to dogs but harmless to humans. Some chemicals cause harm at high doses in animal studies, but their impact at lower food consumption levels may differ significantly. Therefore, animal study results don’t necessarily predict human effects.

Also, conducting specific human testing for GRAS additives is not a typical requirement. The emphasis lies on safety assessments and expert consensus rather than direct human trials. Perhaps this should change?

If you have any questions regarding GRAS, food additives or processed foods you regularly buy in the supermarket, let us know in the comment section below.

Michaela is a qualified food technologist, originally from the Czech Republic, where she successfully graduated and earned a Master’s degree from University of Chemistry and Technology. Michaela’s field of study was chemistry and analysis of food and natural products, and upon finishing her studies she became a part of an R&D team focusing on nutritional plant-based food…

References

(1) Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS). U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/generally-recognized-safe-gras

(2) How Upton Sinclair’s ‘The Jungle’ Led to US Food Safety Reforms. History.com. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/news/upton-sinclair-the-jungle-us-food-safety-reforms

(3) The 19th-Century Swill Milk Scandal That Poisoned Infants With Whiskey Runoff. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/swill-milk-scandal-new-york-city

(4) Wax PM. Elixirs, diluents, and the passage of the 1938 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Mar 15;122(6):456-61. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00009. PMID: 7856995.

(5) GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Database. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/gras-substances-scogs-database

(6) How FSANZ ensures the safety of food additives. Food Standards Australia and New Zealand. Retrieved from https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/additives/additivecontrol