Fletcher Sunde

Certified Meditation Coach, MSc (Biology)

The word meditation comes from Latin “meditatum” which means “to ponder” and prior to the introduction of eastern meditation, this word was used to describe deep, personal, philosophical thought.

In today’s article we will look into:

- history of meditation

- current research on meditation

- health benefits and possible risks

First, we’ll start with understanding what meditation really is, and what are the most commonly used types of meditation in the West.

What is meditation?

Meditation is a practice where an individual uses a technique to focus the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity to train attention and awareness and generate calmness and insight.

By practicing meditation one can achieve greater levels of clarity and higher levels of focus and attention than we naturally achieve in our day-to-day lives.

Meditation is a training regime for our brain

Similarly to how we train the muscles in our body to become stronger, our brain can be conditioned to be more able to tackle the ins and outs of life.

When we meditate, we increase the integration of our brain and make us more resilient to the stresses that we face.

To illustrate this, imagine yourself competing in a marathon. If you did no training and just showed up on the day of the race, it would be very difficult to do well.

However, if you trained every day you would have no problem getting a good result. The same thing goes for the trials of life.

If we exercise our brain daily, we can be sure we’re always at peak performance and when we encounter obstacles, we’re more suited to cope.

Different types of meditation

There are hundreds of different types of meditation. Some of the most common these days are:

- Mindfulness meditation

- Transcendental meditation

- Yoga nidra

- Vipassana meditation

- Guided meditations or visualizations

These types of meditation vary tremendously in their techniques and outcomes, and different forms of meditative practices are associated with different patterns/brain waves of brain activity.

History and origin of meditation

Most scholars agree that meditation, as we know it today, has its roots in ancient India, somewhere between 3000 and 5000 BCE.

Cave drawings from this time show people sitting in meditative postures with their eyes closed, suggesting meditation was well utilised at the time.

It may be that contemplative practices predate this by quite some time and some and really, it depends on how meditation is defined.

Some suggest the Indus Valley Civilisation of ancient India took inspiration for meditation from Egyptians since Egyptian hieroglyphs show people and pharaohs in yogic postures.[1]

Others have even suggested that meditation might be as old as humanity itself. Perhaps even Neanderthals meditated in some form or another.[1]

Meditation and Ancient India

The earliest written records of meditation exist in the Vedic scriptures of the Indus Valley Civilisation, written between 1200 BCE and 1500 BCE.

The Vedas reference “asanas” or positions, which, while used to refer to most yoga positions today, originally referred only to sitting meditation.

RELATED — The Origins of Yoga: History, Development and Modern Times

Meditation and Ancient Asia

While the earliest histories may be a little diffuse, things start to become clearer following the life and time of Siddhartha Gautama, who is also known as Buddha (563 BCE – 480 BCE).

The life of the Buddha, and particularly his enlightenment, mark the start of the Buddhist tradition and the crystallisation of mindfulness meditation as a way to reach enlightenment.

While some techniques such as Vedic meditation and practises giving rise to Kemetic yoga predate traditional mindfulness, in many ways, Buddhist mindfulness, and particularly its focus on awareness, represents the roots of the tree from which most other modern meditative techniques have arisen.

Around the time of the Buddha, meditation was also growing in popularity in China, with the philosopher and teacher Lao-Tze, the founder of Taoism, promoting the value of wisdom in silence.

Meditation and modern times

From before the time of the Buddha, meditation existed in the East in many forms and indeed, new meditation practices continued to be developed for many years.

Vipassana meditation was redeveloped from ancient teachings in Burma in the 18th century. This led to the Vipassana movement of the 20th century.

Transcendental meditation was developed by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in India in the 1950s.

For over 5000 years the East has been a rich fertile ground for connection with the divine and the attainment of tranquility and wisdom through meditation.

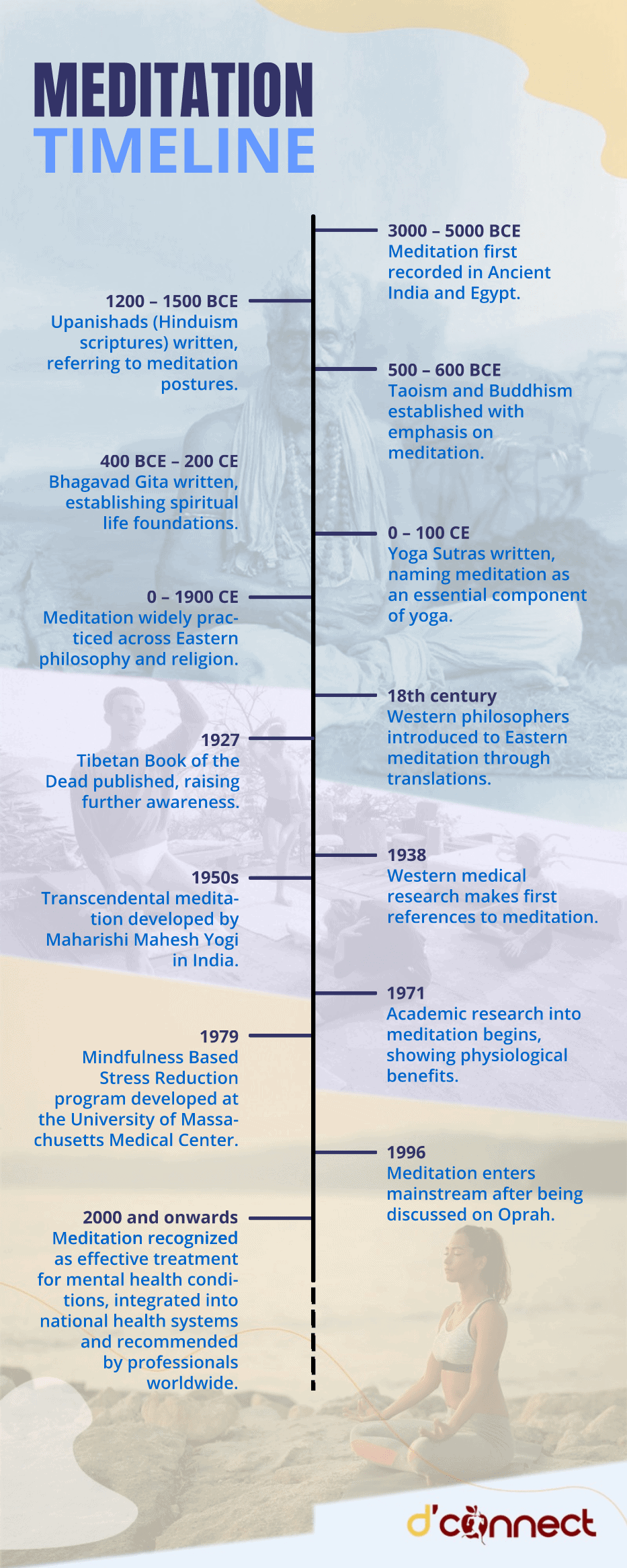

Meditation — timeline

To better understand and visualise the history of meditation, we have also created an illustration (see below).

- 3000 – 5000 BCE: First records of meditation from cave drawings in Ancient India. Hieroglyphs also show forms of meditation practised in Ancient Egypt.

- 1200 – 1500 BCE: The Upanishads (Vedic scriptures providing the basis for Hinduism) are written with various references to “asanas” (meditation postures).

- 500 – 600 BCE: Lao Tzu develops Taoism in China and Sidartha Guttama gains enlightenment in India, establishing Buddhism. Both religions have a heavy emphasis on meditation.

- 400 BCE – 200 CE: The Bhagavad Gita is written, laying out the foundations of how to live a spiritual life.

- 0 – 100 CE: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are written, naming meditation as one of the eight limbs of yoga required to achieve purusha (conscious awareness).

- 0 – 1900 CE: Meditation is almost ubiquitous across eastern philosophy and religion.

- 18th century: Medawi redevelops vipassana meditation from ancient teachings in Burma.

- 18th century: Translations of books such as the Bhagavad Gita and The Upanishads reach western philosophers, giving the West its first impression of eastern meditation.

- 1927: The Tibetan Book of the Dead is published, further raising awareness of eastern meditation.

- 1938: The first references to meditation in western medical research (Walter, 1938).[2]

- 1950s: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi develops transcendental meditation in India and brings the technique to America.

- 1971: Robert Wallace publishes about the physiologically beneficial effects of transcendental meditation in the journal Science, heralding the beginning of decades of academic research into meditation.

- 1979: John Kabit-Zinn opens the Stress Reduction Clinic and develops the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction programme at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center.

- 1996: Depak Chopra is interviewed on Oprah and meditation has fully entered the mainstream.

- 2000 and onwards: Meditation is fully accepted as an effective treatment for numerous mental health conditions including stress, anxiety, depression and PTSD. Meditation is integrated with national health systems and recommended by health professionals across the world.

Note — feel free to download or share this illustration.

Meditation, arrival to the West and notable individuals

The first references to eastern meditation in the West are in the 1700s and come from translations of ancient eastern scripts such as The Upanishads, The Bhagavad-Gita and the Buddhist Pali Canon.

The word meditation comes from Latin “meditatum” which means “to ponder” and prior to the introduction of eastern meditation, this word was used to describe deep, personal, philosophical thought.

To an observer, a state of deep thought would have been what eastern meditation resembled, though we know that this is often not what we are trying to achieve, or at least not in a direct way.

Until the very late 19th and then 20th century, this form of eastern meditation remained the interest of intellectuals, particularly philosophers, and was by no means common practise.

In 1893 the Indian Guru Swami Vivekananda delivered an iconic speech to the World’s Parliament of Religions, where he introduced Hinduism to America and called for tolerance of all religions.

This sparked an interest in Eastern philosophy in the West and by the 1930s, the first references to meditation in academic research were made.

By the 1950s, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi had emigrated to America, bringing his Transcendental meditation practise, which then became popularised, in particular, by The Beatles and other celebrities. At this time meditation was still associated with the counterculture and was not part of the mainstream.

Meditation entered the mainstream through the work of John Kabit-Zinn, who in 1979 opened the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts and developed the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction programme.

Much credit is also given to Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk Thích Nhất Hạnh, who, from his home in France, toured extensively across the west and wrote numerous entry level books on meditation and mindfulness following his exile from Vietnam in 1966.

By the late 1990s Oprah was interviewing Depak Choprah and meditation was well and truly recognised for its benefits to mental health and inner well-being.

Research on meditation

In the past 100 years, academic research on meditation has been vast and varied. Google scholar returns over 100,000 entries, including articles, reviews and books, on the term “meditation”, and we will take a detailed look at this research in our future articles.

What follows is an overview of the last 50 years.

In the early 1970s when meditation research started to gain a footing, the focus was on the physiological aspects of meditation, which showed that meditation:

- slows respiration

- slows down heart rate

- reduces skin electrical conductivity

- reduces blood lactate levels[3]

These effects, coupled with proven variations in neurotransmitter frequency, reduction in body temperature and increases in sense perception suggested the link between meditation and the autonomic nervous system.

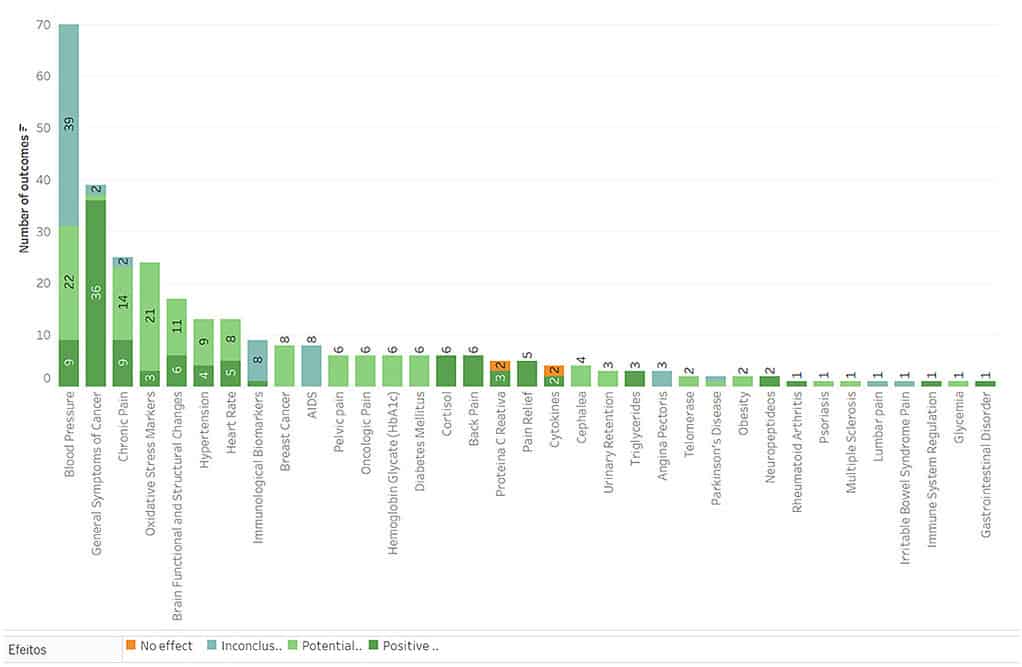

Source: Portella, C. Meditation: Evidence Map of Systematic Reviews. Frontiers. (2021)

In the following decades, research was dominated by examining changes in the brain as a result of meditation. These included changes in brain dynamics, patterns of brain waves and changes in brain structure (which are numerous).

These days, significant attention is being paid to an emerging field called Psychoneuroimmunology.

Psychoneuroimmunology is the study of the connection between our state of mind and our immunity and physical health.

It acknowledges there are links between nervous and immune systems and focuses on the relationship between psychological processes and physical health.

Research is beginning to show that we can literally meditate our way to good health, which we’ll discuss in our future articles.

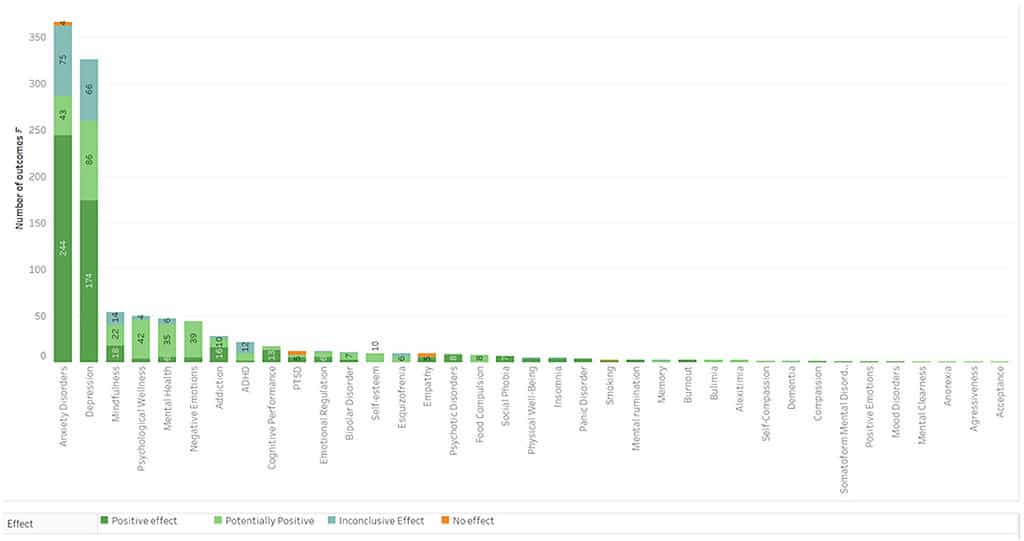

Health benefits of meditation

Numerous scientific studies and peer reviewed articles have been conducted and published on the health benefits of meditation.

These studies ran alongside thousands of articles and research that showed real and concrete changes in physical and mental health, recording positive impacts on:

- decreasing levels of stress and anxiety

- cultivating kindness and compassion

- enhancing self awareness

- helping control addictive behaviours

- helping control physical pain

- allowing and encouraging neuroplasticity

- delaying the onset and reducing the impacts of neurodegenerative diseases

- healing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

- mediating impulse control

- building emotional resilience and promoting emotional health

- improving focus and lengthening our attention span

- improving memory

- improving executive function and cognition

- improving sleep quality[4]

RELATED — Why we sleep: The role of sleep in our healthy life

Source: Portella, C. Meditation: Evidence Map of Systematic Reviews. Frontiers. (2021)

Also, scientists recorded increases in the efficacy of vaccinations and prolonged retention of lymphocytes in HIV patients following meditation sessions.

Side effects and possible risks of meditation

When starting any new practice, it’s important to have an idea of whether negative side effects exist. For the most part, research into meditation has been on its positive effects on mental health.

Certainly, there have been reports of negative side effects as a result of practising meditation. These include:

- reliving troubling experiences and emotions

- loss of motivation associated with questioning reality

- physical pain

- damage to one’s sense of self

- hallucinations

- hospitalisation for psychosis

That said, a 2020 review of multiple studies covering 2155 participants of Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction programmes concluded that the chances of having a negative experience during a mindfulness programme were no greater than the chances of someone having such an experience outside of a programme.[5]

Similarly, another 2020 review examining 83 studies (a total of 6,703 participants) found that, while negative experiences were reported, the rate was very nearly identical to the chances of having a negative experience from different form of psychotherapy (about 8%).[6]

Meditation may not be suitable for people with psychosis

Some researchers have suggested that individuals with psychosis or other related conditions should avoid meditation due to its mechanism of detaching one from one’s sense of identity and reality.[7,8]

Those dealing with such conditions should seek medical advice before trying meditation.

There is no doubt that meditation can bring up uncomfortable feelings and make us question why and how we do things, but some would say that this is the point.

The best advice I can offer is to learn from a reputable teacher who can give you real time advice and instruction and to take it slowly.

Don’t push yourself to develop too quickly. Spend some time building your foundation before you jump head first into a 10-day vipassana retreat!

Related Questions

1.What type of healing does meditation provide?

Meditation provides healing for our mental and emotional health.

It helps to integrate parts of our brain we don’t access or avoid due to the suffering that we are experiencing. In this way, it has the unique ability to help a practitioner navigate whatever mental health challenges they are going through.

2. Is chanting the same as meditation?

No, chanting is not the same as meditation.

While this field of research is still young, a recent study suggests that chanting produces different brain wave patterns than mindfulness meditation, though may have similar characteristics to other forms of meditation such as transcendental meditation.[9]

Chanting is often about giving reverence, which can help to balance our mind and make it easier to enter meditative states.

3. Can meditation reduce anger?

Yes, absolutely.

Meditation teaches us acceptance and to go with the flow. With practice, reduction in feelings of anger and changes in impulse control can be dramatic.

4. What is the best type of meditation for anxiety?

Almost any meditation will help, though the best are meditations that have a single focus, such as meditations that focus on the breath (as opposed to meditations with changing focuses, like guided meditations and visualisations).

Mindfulness meditation has been scientifically proven to help alleviate anxiety as it increases alpha and decreases beta brain waves.

Anxiety is typically characterised by increased beta and decreased alpha brain activity.

5. Does position matter when meditating?

For most meditations an alert yet relaxed, upright sitting position is desirable.

Sitting in this way allows for:

- airways to be open

- promotes alertness

- provides a comfortable way to sit for the duration of the meditation

RELATED — Introduction to Breathing: Our foundation of health

Some meditations are also done laying down while there are also active meditations such as walking and eating meditation.

RELATED — A Guide to Mindful Eating

If you would like to know when another article on meditation will be coming out, feel free to Subscribe to our Newsletter, and we’ll let you know in advance.

Fletcher Sunde is a qualified meditation coach and founder of Meditate with Fletch. Fletcher first accessed meditation through his own experience with depression and addiction and, after gaining an appreciation for the power of meditation as a tool to help overcome mental health challenges, began teaching in early 2020.

With a university background in science and a depth of knowledge in Buddhist practice, Fletcher straddles the divide between western philosophical thought and traditional eastern teachings.

Fletcher meets people at whatever level they are coming from and has formed a syllabus that is both grounded in our everyday experience and insightful enough to ask meaningful questions of students.

References

(1) Eifring, H., Davanger, S. & Hersoug, A. G. (Eds) (2008) Fighting Stress – Reviews of Meditation Research. ACEM Publishing

(2) Walter, W. G. (1938). Critical Review: The Technique and Application of Electro-Encephalaography. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1088109/pdf/jnpsychiatry00020-0059.pdf

(3) Wallace, R. (1970). Physiological effects of transcendental meditation. Science.

(4) Thomas, J. W. & Cohen, M. (2014). A methodological review of meditation research. Psychiatry. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00074/full

(5) Hirshberg, M., Goldberg, S., Rosenkranz, M., & Davidson, R. (2022). Prevalence of harm in mindfulness-based stress reduction. Psychological Medicine.

(6) Farias, M., Maraldi, E., Wallenkampf, K.C. & Lucchetti, G., (2020). Adverse events in meditation practices and meditation-based therapies: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatry Scandanavia.

(7) Canter, P. H. (2003). The therapeutic effects of meditation. Psychiatry. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1125975/

(8) McGee, M. (2008). Meditation and Psychiatry. BMJ. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2719544/

(9) Gao, J., Leung, H. K., Wu, B. W. Y., Skouras, S. & Sik H. H. (2019). The neurophysiological correlates of religious chanting. Scientific Reports. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-40200-w