Kim Hoffmann

NASM CES (Corrective Exercise Specialist) and Certified Personal Trainer

As many of us will find out, ageing is not fun. Apart from our physical appearance going south, our ability to move and do things we used to take for granted diminishes with each passing year.

In this article, we’ll discuss how ageing leads to sarcopenia and muscle loss, and how through exercise we can reverse the muscle loss and delay ageing.

Ageing and our body

Muscles grow and are broken down throughout our lives. This is a normal process and when everything is in balance, we keep our strength, or are at least able to build it back up.

However, as we age, our body becomes resistant to the normal growth signals and starts to normalise breaking down muscle. This is often accelerated by inflammation and the body’s inability to fight this.

Other physical factors are denervation and loss of type II muscle fibres. Then there are a few environmental factors such as:

- becoming more and more sedentary (after retirement, for example)

- chronic diseases

- inflammation

- insulin resistance

- lack of good and sufficient nutrition

- changes in endocrine function (for example menopause)

When this is combined with a weakened immunity, we are putting ourselves at risk from many different diseases.[1]

What is sarcopenia?

Sarcopenia is age-related muscle loss and function. As we age, usually after we turn 50, we lose about 0.5 – 1% of skeletal muscle per year.[2] It’s natural to lose muscle size and strength.

Sarcopenia is estimated to affect 5-13% of people 60 years and over, and 11-50% of people 80 years and above and it affects both sexes equally.[3]

People are considered to have sarcopenia if they are:

- bed-ridden

- can’t stand up from a chair independently

- have a walking pace of less than 1 meter per second[4]

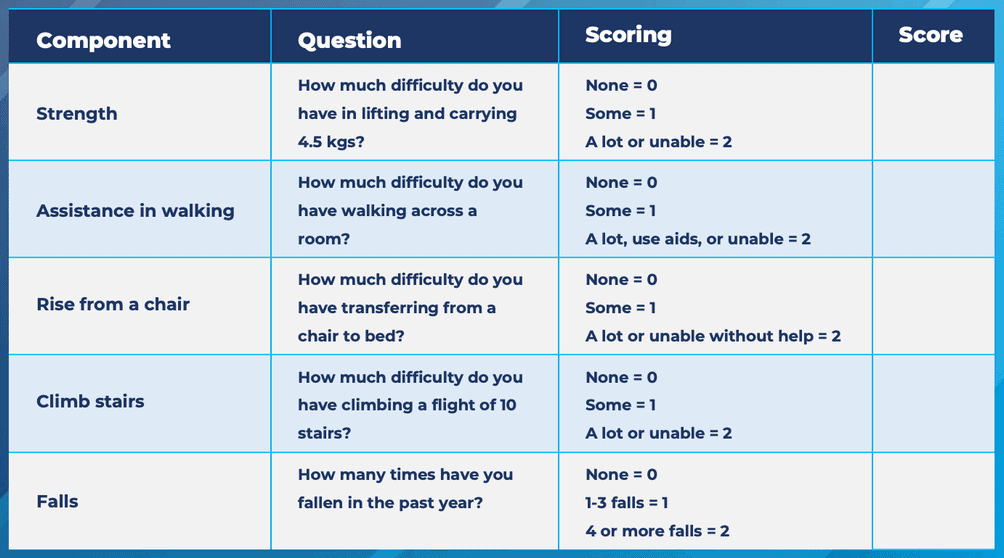

Sarcopenia is diagnosed through the SARC-F questionnaire. This determines how much of a risk of sarcopenia we’re having based on the scores of the questions:

The higher the score, the higher our risk of sarcopenia.

People with the following conditions have a greater chance of developing sarcopenia:

- COPD

- Chronic Heart Failure

- HIV

- Cancer

- Diabetes

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

People with these conditions can’t exercise like a healthy person can, so losing muscle strength is a consequence of this condition. This doesn’t mean they shouldn’t do strength training. They only need to adapt their training and work with their abilities.

Why is good muscle strength important?

Having good muscle strength is important for many reasons, such as:

- healthy metabolic rate

- being able to perform daily activities and chores

- good balance and healthy bones and joints

- reduced risk of chronic diseases

- better endurance

When we lose muscle strength, we will lose all of the aforementioned benefits.

A healthy metabolism is important because this is what burns calories. Muscles are more metabolically active than fat, which means that having strong muscles burns more calories at rest.

This helps to keep us at a healthy weight which is good for our joints. It also fights off chronic diseases because it lowers blood sugar levels and blood pressure.

Strong muscles also make sure that if we stumble or trip, we don’t lose our balance and break a bone. As we age, our balance can get affected by muscle loss, loss of coordination and slower reaction time. It may seem like a simple stumble or slip, but if we break a bone, it could be the start of a long-term disability.

Strong muscles also help us if we stumble or trip

A study from 2023 showed that people who do lifelong strength training are able to keep their fast twitch muscle fibres at an older age.[5]

Fast twitch muscle fibres are important for

- speed

- strength

- power

In this study they found that men who did strength training throughout their lives showed similar distribution of type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibres compared to the young men in the study.

In comparison, older men who only did endurance training showed signs of muscle atrophy and less distribution of type II muscle fibres than the older men who did strength training.

Osteoporosis, or brittle bone disease, is also a risk when we age, though it mostly affects women. That’s because of the loss of oestrogen during menopause.

RELATED — Menopause: Guide to Signs and Symptoms

Both men and women have oestrogen, but the levels of this hormone are much higher in women. Oestrogen helps build and repair muscles and bones. When we lose it, we lose this ability as well.

Oestrogen helps build and repair muscles and bones

Strength training helps against osteoporosis and falls, because it improves coordination, balance and bone density. So, the stronger and better prepared we are to begin with, the longer we will be able to enjoy good quality of life, even if we stumble or fall.

Many older adults fear falling, even if they haven’t fallen before. This fear can lead to avoiding activities. Staying active is one of the most important things we can do to prevent falls.

Progression of sarcopenia as we age

Over the course of our adult lives we will naturally lose our muscle mass and strength and all the benefits that come with our muscles.

Decline starts in our 50s and accelerates after the age of 75

There is still a lot unknown about sarcopenia, and the rate at which the decline happens depends on how active we are and how well we eat, among other things.

A study done in 2021 researched the progression of sarcopenia over the course of 12 years. They studied more than 3000 men with different stages of sarcopenia:

They found that it’s a two-way dynamic condition that changes dramatically over the long term. In all three groups, there were barely any changes to the condition after one year.

The changes became more pronounced after five and 10 years.

Group A

Participants with no sarcopenia had a 17.1% chance of developing probable sarcopenia, a 5.1% chance to develop sarcopenia and a 40.4% chance of not transitioning at all.

Group B

Those that had probable sarcopenia to begin with had a 10.3% chance to develop sarcopenia over the course of five years and a 10.7% chance to revert it.

Group C

People with sarcopenia had chances to revert to probable sarcopenia ranging from 8.2% (at 5 years) to 4.7% (at 10 years), and a 70.9% chance of dying after 10 years.

Another study, Murphy et al. from 2013, showed that very few people (both men and women) aged 70-79 years who did not have sarcopenia, also did not develop it over the course of the 9-year study.[7]

What both studies found to be contributing factors to developing sarcopenia are

- older age

- higher BMI

- pain

Other factors such as male sex, current smoking habits, and a higher number of chronic diseases all brought a higher risk of sarcopenia progression.

How to slow down sarcopenia?

The most important thing we can do to slow down age-related muscle loss is strength training. Making sure we eat enough protein is another major factor.

We’ll cover this in more detail in the next article.

Exercise and sarcopenia

We covered the benefits and the strength training for the general population in the article How to get back into exercise after a long hiatus.

In this article we’ll focus on strength training for the elderly population. Even though there is no difference in the way we should train, there are a few pointers that can make starting strength training at a later age a bit less daunting.

The general advice is 2 sessions of strength training a week, according to the guidelines of the Ministry of Health NZ.[8] This is separate from any aerobic exercise that the Ministry recommends.

The guidelines for aerobic exercise are to do 30 minutes a day, 5 days per week, of moderate intensity exercise, or 15 minutes of vigorous intensity.

As far as strength training goes, I’d recommend 3-4 times per week, because it gives you better (and faster) results. But, how much you exercise eventually depends on your schedule as well as your abilities and conditions.

Depending on your experience and activity levels, you may need to start at a different stage. People who are very sedentary or have never done exercise before should start with basic exercises and very little or no weight, like standing up from a chair or doing a push-up against the wall. For these people, I would highly recommend hiring a trainer to prevent injuries.

As far as the repetitions and sets go, I would start with 8-12 reps if you’re a beginner with lighter weight and 5-10 if you’re more experienced, with heavier weight.

For strength training workouts, you should aim to use as heavy a weight as possible for very few repetitions (up to 6), but I would not recommend doing this without a professional by your side.

What types of exercises should you do?

As briefly mentioned before, a squat or pushup are good exercises. Deadlifts and any kind of row are good too. I would also recommend doing some overhead pushes and farmer’s/suitcase carry for grip and core.

What all these exercises have in common is that they are functional exercises that translate to movements in everyday life.

You can use the machines as a way to get stronger but ideally you use movements from everyday life. As an example, the squat exercise is the equivalent to getting up from a chair.

The deadlift is similar to picking something up off the floor. Grip strength is important for opening jars or bottles. If you want to build overall strength and/or are short on time, doing exercises like the above-mentioned are a great start.

If you have access to a gym and you’re comfortable using the equipment (if not, employ a trainer), you can always use the cable machines, barbells and dumbbells to change things up.

Instead of a pushup, you might do a barbell or dumbbell bench press, or the chest press machine. Instead of a bent over row, you could do a cable lat pull down, a cable row or the row machine.

This type of training should be a lifelong commitment, no matter what age you’re starting at.

Diet and Sarcopenia

Along with regular exercise, a balanced healthy diet is important for maintaining muscle mass and preventing the onset of sarcopenia. This includes an adequate intake of energy (total calorie requirements), protein, and various vitamins and minerals.[1]

Important nutrients to protect against age-related muscle mass:

- Protein and amino acids[1,2,3,4,5]

- Antioxidant nutrients (e.g. vitamin C and vitamin E)

- Omega-3 fatty acid

- Mineral and trace elements (e.g. selenium, magnesium, potassium, zinc, iron, and phosphorous)

- Vitamin D[9,10]

Amino acids are the building blocks of protein, and can be found in varying amounts in animal and plant-based sources.

A diet with adequate amounts of protein, along with other essential nutrients listed above, has shown to be protective against sarcopenia.[9,10]

Related Questions

1. Do I need to use weights in order to improve my strength?

The short answer is yes.

At any age, if we want to increase muscle strength or size, we need to challenge our body to create adaptations. Without weights there is no challenge for the body to change.

2. Is sarcopenia reversible?

Yes, it is, but resistance training needs to be part of our exercise routine in order to reverse it. Endurance training alone is not enough.

3. Can I start weight lifting in my 60s or above?

Totally! It’s never too late to start.

4. What is the best way for the elderly to regain muscle mass?

Strength training and a good diet!

5. What vitamins and minerals slow down age-related muscle loss?

Vitamin D is a big one to keep our bones healthy and strong. Omega-3 helps fight inflammation which could be a cause for sarcopenia, according to some research. But the most important thing is to eat enough protein.

RELATED — Vitamin D: The sunshine hormone for stronger bones

Kim Hoffmann is a certified Personal Trainer and Corrective Exercise Specialist based in Auckland. She also specialises in women’s health and fitness by taking into consideration the menstrual cycle and hormones and implementing them in different workout plans. The workout methods and routines include free weights, suspension straps and boxing, as well as strength training and high intensity…

If you would like to learn more about Kim, see Expert: Kim Hoffman.

References

(1) Dupont, J., Dedeyne, L., Dalle, S., Koppo, K., Gielen, E. (2019). The role of omega-3 in the prevention and treatment of sarcopenia. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6583677/

(2) The Australian and New Zealand Society for Sarcopenia and Frailty Research. 2024. https://anzssfr.org/

(3) Ardeljan, A. D., Hurezeanu, R. 2023. Sarcopenia. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560813/

(4) J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2011). Sarcopenia: An Undiagnosed Condition in Older Adults. Current Consensus Definition: Prevalence, Etiology, and Consequences. Doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3377163/

(5) Tøien, T., Lindberg Nielsen, J., Berg, O. K., Forsberg Brobakken, M.,Kwak Nieberg, S., Espedal, L., Malmo, T., Frandsen, U., Aagaard, P., Wang, E. (2023) The impact of life-long strength versus endurance training on muscle fiber morphology and phenotype composition in older men. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10979801/

(6) Trecvisan, C., Vetrano, D. L., Calvani, R., Picca, A., Welmer, A. K. (2021) Twelve‐year sarcopenia trajectories in older adults: results from a population‐based study. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12875 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8818646/#jcsm12875-supitem-0001

(7) Murphy, R. A., Ip, E. H., Zhang, Q., Boudreau, R. M., Cawthon, P. M., Newman, A. B., Tylavsky, F. A., Visser, M., Goodpaster, B. H., Harris, T. B. 2013. Transition to Sarcopenia and Determinants of Transitions in Older Adults: A Population-Based Study. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt131 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4022098/

(8) Ministry of Health. 2013. Guidelines on Physical Activity for Older People (aged 65 years and over). Wellington: Ministry of Health. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/2013-01/guidelines-on-physical-activity-older-people-jan13-v3.pdf)

(9) Papadopoulou SK, Detopoulou P, Voulgaridou G, Tsoumana D, Spanoudaki M, Sadikou F, Papadopoulou VG, Zidrou C, Chatziprodromidou IP, Giaginis C, Nikolaidis P. Mediterranean diet and sarcopenia features in apparently healthy adults over 65 years: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2023 Feb 22;15(5):1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051104

(10) Jang EH, Han YJ, Jang SE, Lee S. Association between diet quality and sarcopenia in older adults: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Life. 2021 Aug 10;11(8):811. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11080811