Megan Rodden

(BCS, DipNat, MedHerb, NMHNZ)

Allergy season is in full swing and for some of us sneezing, runny nose, and itchy eyes are on the way.

For those who struggle with allergies, pollen may not be the only issue, since allergies may be triggered by food or other airborne particles like dust or dander.

Natural remedies for allergies can help to manage symptoms but also work on creating a more balanced immune system to dampen down the response.

In this article we will share 5 Natural Remedies for Allergies that you can start using today as a part of your diet and additional supplementation.

Understanding seasonal allergies

The nasal cavity is lined with a layer of cells that make mucus, called mucosa, which is part of the body’s first line of defence against pathogens.

Allergic rhinitis is also known as hay fever

It can be seasonal, flaring mainly in spring and summer or perennial, occurring year round, triggered by indoor particles as well.

In allergic rhinitis, the immune system becomes hypersensitive, reacting to everyday substances that we inhale like pollen and cat hair.

This immune response sets off the release of chemicals like histamine, which plays a major role in hay fever symptoms.[1]

Common hay fever symptoms

- Watery nasal discharge (runny nose)

- Itchy eyes

- Itchy nose

- Sneezing

- Asthma and eczema (often coexist with hay fever)

- Tiredness (if symptoms go on for a long time)

Common hay fever triggers

- Seasonal (plant allergens)

- Spring (tree pollens)

- Summer (grass pollens)

- Winter (weed pollens)

- Perennial (indoor allergens)

- Pet dander (cats or dogs)

- Dust (from dust mites faeces)

- Fungus and moulds (especially black mould).

Natural approach to seasonal allergies

Fortunately, herbal remedies can help reduce the response to allergens and nutrition can be used to support the body in becoming less reactive.

The 5 natural remedies for seasonal allergies that we’ll discuss are herbs

- Albizia

- Baikal Skullcap

- Eyebright

and nutrients

- Quercetin

- Bromelain

Albizia (Albizia lebbeck, Pit Shirish Shirisha)

Albizia is a medium deciduous tree with cream coloured flowers, that grows well in Australia, India, and Thailand and is considered a weed in Queensland.

Source: Lana @ Unsplash

Albizia has been used as a traditional Ayurvedic remedy for centuries.

Albizia has been used as a traditional Ayurvedic remedy for centuries.

Mechanism of action (how it works)

Albizia contains constituents that block signals from chemicals which cause hay fever symptoms. It also stabilises mast cells involved.[2]

These main active constituents are

- Saponins

- Tannins

- Flavonoids

The stem bark is used for its antiallergic properties.

Research

The anti-allergic activity of Albizia has been studied and a number of properties have been documented.[3,4]

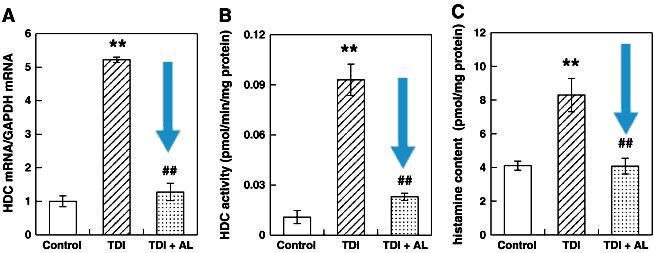

Extracts of the leaf and bark of Albizia have been tested in vitro and in vivo showing similar mast stabilising effects as the allergy drug cromoglycate and demonstrated anti-allergic action against atopic allergy.

Albizia was compared with cromoglycate and prednisolone to assess allergic action on mast cells and Albizia was found to act similarly to the anti allergy drug and to inhibit the early stage of the allergy process in sensitised rats.[5]

Source: Mizuguchi, H. Albizia lebbeck suppresses histamine signaling by the inhibition of histamine H1 receptor and histidine decarboxylase gene transcriptions. Internal Immunopharmacology. (2011)

How to take it

- Dried leaf and bark tea infusion 3–6 gm/day.

- Tincture 3–8 ml per day.

- Tea infusion instructions: Brew 1 teaspoon of dried leaf and bark of albizia in boiling water for 5 minutes and sip while warm.

Safety and risks

Taking Albizia together with antihistamine medications may add to the effects of them and may be a beneficial interaction.

Baikal Skullcap (Scutellaria baicalensis, Chinese skullcap, Haung qin)

Baikal skullcap is a traditional Chinese herb with sweet purple flowers with a cap-shaped top. It is a shrub that belongs to the mint family, Lamiaceae and grows only to around 30cm in height.

Source: Lena @ Pexels

The plant is known in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) as Huang Qin and used for over 2000 years to clear heat and dry dampness.

Mechanism of action (how it works)

The active properties of Baikal skullcap

- Flavones

- Baicalein

- Wogonin

stop the release of allergy chemicals.

The roots are mainly used as they are believed to have the most of these medicinal properties and most studies centre around extracts of the root, however, research has also begun to uncover properties of the aerial parts (leaves, stem, flowers).[8]

Research

The constituent baicalein has been shown to have anti-allergic action, stopping the release of histamine and other chemicals that cause inflammation.[9]

The antiallergic effect of baikal skullcap was demonstrated in human and animal mast cells, and in one of the studies constituent baicalein was found to be more potent than the allergy drug azelastine.

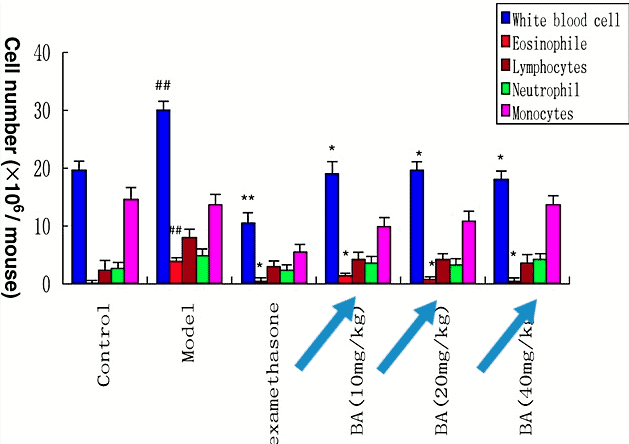

Source: Ma, C. Anti-asthmatic Effects of Baicalin in a Mouse Model of Allergic Asthma. Phytotherapy Research, Volume 28. (2014)

The study looked at 8 different compounds in healthy people and steroid dependent allergic asthmatics and baicalein was 5–10 times more potent than the drug.[10,11]

The water extract of baikal skullcap has been shown to significantly inhibit the production of inflammatory cells.[12]

How to take it

- Dried herb tea 2–3 gm day

- Tincture 3–7 ml per day

- Tea infusion instructions: Brew 1 teaspoon of dried herb in boiling water for 5–10 minutes and sip warm.

Take with a meal as this may help increase the uptake of the active properties.

Safety and risks

Baikal Skullcap is generally well tolerated. However, it’s advisable to avoid it in the first trimester of pregnancy and with antidiabetic drugs as it may further lower blood sugars.

Also, look for sustainable sources as it is an endangered plant.

Eyebright (Euphrasia rostkoviana, Euphrasia, Casse-Lunettes)

Eyebright is a small shrub with small mauvish white flowers that grows with grasses in pastures. Eyebright has been used in Europe for centuries for eye conditions.

Source: Lena @ Pexels

Mechanism of action (how it works)

The anticatarrhal properties of eyebright reduces watery nasal discharge and supports symptoms with anti-allergic activity and mucous membrane tonic properties.

Active constituents of iridoid glycosides and flavonoids. The top parts of the flowering herb are used.

Research

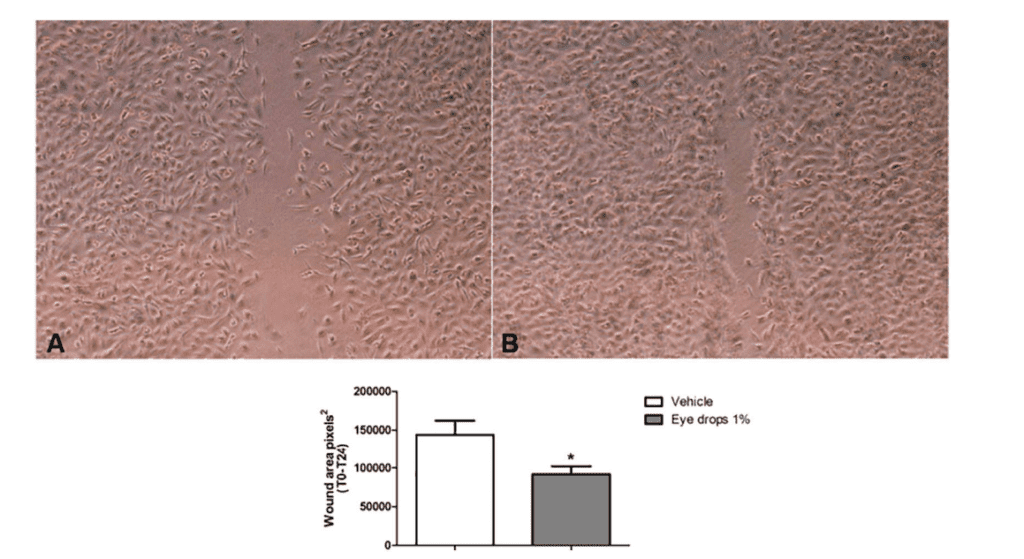

Iridoid glycosides have been thoroughly studied and the traditional use of Eyebright for eye irritation and reactions, known as ocular allergy, have been documented and supported by some clinical trials.[13,14]

Studies on human corneal epithelial cells showed promising effects for the use of both ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of eyebright, which reduced inflammatory cells associated with allergy.[15]

One prospective, multi centred, multinational trial concluded that eyebright eye drops were both safe and effective for treating conditions of inflammation of the conjunctiva (thin outer eye layer).

Source: D'Ambrosio, M. Pharmacological activities of an eye drop containing Matricaria chamomilla and Euphrasia officinalis extracts in UVB-induced oxidative stress and inflammation of human corneal cells. Journal of Photochemistry & Photobiology. (2017)

A complete recovery was seen in 81.5% of patients and it was rated effective and tolerable by 85% of participants.[16]

How to take it

Eyebright tea

One cup three times daily.

The tea is prepared by steeping 2–4 grams of dried eyebright in 150ml of boiling water for 5–10 minutes. Once done, strain it.

Eyebright eye wash

This eye bath can assist us when our eyes are irritated and itchy as a result of hay fever.

Decoction – Place ½ teaspoon of dried or fresh herb in 50ml of water and boil for 10 minutes. Strain, allow to cool, then refrigerate in an airtight sterile container.

Use an eye bath or small sterile eye sized container and place over the eye. Tip the head back and blink 2–3 times, rinsing the eye in the solution.

Discard after two days.

Herbal nasal spray

Baikal skullcap – 2 ml tincture

Eyebright or Chamomile – 2 ml tincture

RELATED — Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla)

When the tinctures are mixed, add sea salt and ½ cup of warm purified water.

Add to a sterilised nasal spray bottle and spray before and after exposure to allergy triggers. This should ease and support your irritated and itchy nose.

Safety and risks

Eyebright is generally well tolerated in the form of teas and topical decoctions. Do not ever use tinctures that contain alcohol directly on the eyes and always ensure everything is sterilised.[7]

Quercetin

Quercetin is a plant pigment (flavonoid), which is an antioxidant with anti-inflammatory properties that occurs naturally in foods and can support hay fever symptoms.

Mechanism of action (how it works)

Quercetin stops chemicals in the inflammatory process and helps mast cells involved in allergic reactions to become more stable.[8]

Good food sources

Quercetin can be found in capers, onions, broccoli, apples, berries, grapes, and green tea.

Herbs that are high in quercetin are Elderberry, Ginkgo biloba and St. John’s Wort.

Food source | Quercetin content (mg/100g) |

Capers | 233 |

Onions | 22 |

Cocoa powder | 20 |

Cranberries | 14 |

Lingonberries | 7.4 |

Asparagus, cooked | 7.61 |

Blueberries | 5.05 |

Apple, Red Delicious | 4.7 |

Cherries | 2.64 |

Broccoli, raw | 2.51 |

Apple, Fuji | 2.02 |

Green tea | 2.69 |

Black tea | 1.99 |

Red grapes | 1.38 |

Research

Quercetins anti-allergic properties have been well studied and research proves the capacity for quercetin to treat allergic conditions.[17]

The structure of quercetin is similar to a drug used for allergy and contact dermatitis (cromoglycate) and it has been shown to be more effective in blocking human mast cells.[18]

Quercetin can help with allergies

One study showed a 46–96% inhibition of histamine release by quercetin in 123 patients with perennial allergic rhinitis.

Nasal scrapings in this study were compared after treatment with quercetin and sodium cromoglycate following exposure to dust mite allergens with quercetin resulting in the greatest inhibition of histamine.[19]

How to take it

Recommended daily dose for adults 400–500mg, twice daily.

Capsules are the most convenient way to receive this therapeutic level of quercetin. Taking quercetin together with bromelain and vitamin C increases absorption.[20]

Safety and risks

Quercetin is generally well tolerated when taken at the recommended dosage.

Quercetin may interact with medications that are used for

- Diabetes

- High blood pressure

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

Also, it may theoretically interfere with the absorption of drugs that are metabolised through a specific pathway in the liver (Cytochrome P450 substrates).

Always check with a health professional if taking any medications.

Bromelain

Bromelain is a proteolytic enzyme found in pineapple that may help support allergies because of its anti-inflammatory effects. It has been studied for over 100 years, when it was first isolated in 1894.

Mechanism of action (how it works)

Bromelain has anti-inflammatory and mucolytic (it thins the mucus) properties, and bromelain enzymes break down proteins, including those that contribute to inflammation in reactions.

Good food sources

When it comes to finding bromelain in foods, we should turn to pineapple as it has the highest quantity of bromelain from all foods.

Bromelain is found in high amounts in pineapple

Bromelain is a proteolytic enzyme and although pineapple is the main natural source that has been studied, trace amounts may be found in kiwi fruit, ginger, asparagus, sauerkraut, kimchi, yoghurt, and kefir. This is why it’s important to eat a diverse range of foods.

RELATED — The Healthy Plate Model: Essentials of Healthy Eating

Research

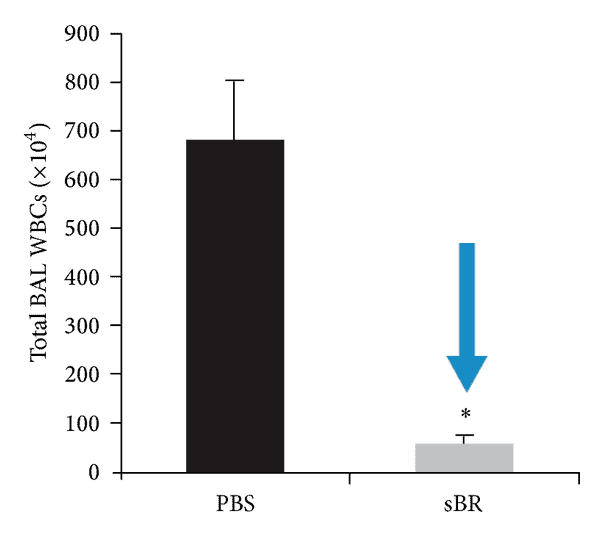

Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of bromelain have been shown and some small studies have highlighted the potential for bromelain to support nasal congestion, helping to breakdown mucus.[21,22,23]

Bromelain reduces inflammation and has a capacity for use as an anti-inflammatory agent in various conditions.[24,25]

A number of studies have shown improvements from bromelain in sinusitis and nasal inflammation. One double blind placebo controlled study of 60 patients observed improvements in inflammation, nasal discharge, breathing, and headache after 3–6 days of treatment with bromelain.[26,27]

Source: Matson, A. Bromelain Inhibits Allergic Sensitization and Murine Asthma via Modulation of Dendritic Cells. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. (2013).

Also, one study in children in Germany with acute sinusitis found bromelain to be both safe and effective, significantly reducing the recovery time from 9 days to 6.[28]

How to take it

It’s best to supplement 500mg a day since it’s difficult to eat enough pineapple to gain the same therapeutic benefits as a specific extract supplement.

Homemade bromelain juice

Making your own pineapple juice can increase the amount of bromelain that you could consume from a pineapple.

Cut 1 pineapple into small pieces making sure to use the whole pineapple, including skin, core, and stem (this is where extra bromelain comes from that you wouldn’t normally be able to eat).

Place everything in a juicer or blender, then sieve through a cheesecloth to extract the juice. Refrigerate the juice and keep in an airtight sterile glass jar or bottle.

Safety and risks

When taken orally or in the diet, pineapple is generally well tolerated. Those with diabetes should avoid excess pineapple consumption because it is high in sugar.

RELATED — Diet and the Brain: Our brain on sugar

Caution before taking bromelain as a supplement with medications and check with a health professional first. For example, bromelain slows blood clotting and should be avoided with warfarin.

Conclusion

These natural remedies are just a few ways that could help ease hay fever symptoms. If you are wanting an individualised prescription of natural remedies, a naturopath or trained herbalist will be able to guide you.

Allergies can be a sign that other body systems are out of balance, in particular the digestive system.

Looking at your diet and lifestyle with the guidance of a natural health practitioner can help you find ways to bring things back into balance.

Related Questions

1. What can happen if hay fever is left untreated?

Untreated hay fever can weaken the immune system and can make us more susceptible to infection, and in particular recurring ear infection in children.

If the nasal area is constantly wet from hay fever this can increase the risk of a fungal infection in the sinuses.

Untreated hay fever may also increase the risk of developing asthma.[29]

2. What food makes hay fever worse?

Foods that are high in histamines can make hay fever worse, such as

- alcohol

- processed meat

- aged cheese

- legumes

3. Is hay fever hereditary and can it be passed on?

Hay fever is influenced by our genes and runs in families but other factors are involved, such as environment and lifestyle.

Having a family member with allergies or asthma increases the risk of hay fever.

Do you suffer from hay fever? Have you considered using natural remedies to ease the symptoms, or do you currently use natural remedies? Let us know in the comments below and share the tips and tricks that have worked for you.

Megan is a qualified, registered naturopath and medical herbalist based in Laingholm, Auckland. She is also a trained journalist with a bachelor’s degree in communication studies and a mother of two, with a passion for plant medicine and holistic nutrition.

A personal health journey has directed Megan to develop a specific interest in digestive and respiratory health, allergies, autoimmune conditions and children’s wellness. You can find more about Megan and her practice at Megan Rodden – Naturopath.

References

(1) Min, YG. (2010). The pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. Apr;2(2):65-76. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/42807480_The_Pathophysiology_Diagnosis_and_Treatment_of_Allergic_Rhinitis

(2) Bone, K. (2007). The Ultimate Herbal Compendium. Phytotherapy press.

(3) Venkatesh, P., Mukherjee, P.K., Kumar, N.S., Bandyopadhyay, A., Fukui, H., Mizuguchi, H., & Islam, N. (2010). Anti-allergic activity of standardized extract of Albizia lebbeck with reference to catechin as a phytomarker, Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology, 32:2, 272-276, DOI: 10.3109/08923970903305481

(4) Shashidhara, S., Bhandarkar, A. V., & Deepak, M. (2008). Comparative evaluation of successive extracts of leaf and stem bark of Albizzia lebbeck for mast cell stabilization activity. Fitoterapia, 79(4), 301–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2008.01.006

(5) Tripathi, R. M., Sen, P. C., & Das, P. K. (1979). Studies on the mechanism of action of Albizzia lebbeck, an Indian indigenous drug used in the treatment of atopic allergy. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 1(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-8741(79)80003-3

(6) Nurul, I. M., Mizuguchi, H., Shahriar, M., Venkatesh, P., Maeyama, K., Mukherjee, P. K., Hattori, M., Choudhuri, M. S., Takeda, N., & Fukui, H. (2011). Albizia lebbeck suppresses histamine signaling by the inhibition of histamine H1 receptor and histidine decarboxylase gene transcriptions. International immunopharmacology, 11(11), 1766–1772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2011.07.003

(7) Balkrishna, A., Sakshi, Chauhan, M., Dabas, A., Arya,V. A Comprehensive Insight into the Phytochemical, Pharmacological Potential, and Traditional Medicinal Uses of Albizia lebbeck (L.) Benth., Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2022, Article ID 5359669, 19 pages, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5359669

(8) Makino, T., Hishida, A., Goda, Y., & Mizukami, H. (2008). Comparison of the major flavonoid content of S. baicalensis, S. lateriflora, and their commercial products. Journal of natural medicines, 62(3), 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11418-008-0230-7

(9) Kim, D. S., Son, E. J., Kim, M., Heo, Y. M., Nam, J. B., Ro, J. Y., & Woo, S. S. (2010). Antiallergic herbal composition from Scutellaria baicalensis and Phyllostachys edulis. Planta medica, 76(7), 678–682. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1240649

(10) Jung, H. S., Kim, M. H., Gwak, N. G., Im, Y. S., Lee, K. Y., Sohn, Y., Choi, H., & Yang, W. M. (2012). Antiallergic effects of Scutellaria baicalensis on inflammation in vivo and in vitro. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 141(1), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2012.02.044

(11) Niitsuma, T., Morita, S., Hayashi, T., Homma, M., & Oka, K. (2001). Effects of absorbed components of saiboku-to on the release of leukotrienes from polymorphonuclear leukocytes of patients with bronchial asthma. Methods and findings in experimental and clinical pharmacology, 23(2), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1358/mf.2001.23.2.627938

(12) Liao, H., Ye, J., Gao, L., & Liu, Y. (2021). The main bioactive compounds of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. for alleviation of inflammatory cytokines: A comprehensive review. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 133, 110917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110917

(13) Mari, A., Ciocarlan, A., Aiello, N., Scartezzini, F., Pizza, C., & D’Ambrosio, M. (2017). Research survey on iridoid and phenylethanoid glycosides among seven populations of Euphrasia rostkoviana Hayne from the Alps. Phytochemistry, 137, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.02.013

(14) Bielory, L., & Heimall, J. (2003). Review of complementary and alternative medicine in treatment of ocular allergies. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology, 3(5), 395–399. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130832-200310000-00013

(15) Paduch, R., Woźniak, A., Niedziela, P., & Rejdak, R. (2014). Assessment of eyebright (euphrasia officinalis L.) extract activity in relation to human corneal cells using in vitro tests. Balkan medical journal, 31(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.5152/balkanmedj.2014.8377

(16) Stoss, M., Michels, C., Peter, E., Beutke, R., & Gorter, R. W. (2000). Prospective cohort trial of Euphrasia single-dose eye drops in conjunctivitis. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.), 6(6), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2000.6.499

(17) Mlcek, J., Jurikova, T., Skrovankova, S., & Sochor, J. (2016). Quercetin and Its Anti-Allergic Immune Response. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 21(5), 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21050623

(18) Weng, Z., Zhang, B., Asadi, S., Sismanopoulos, N., Butcher, A., Fu, X., Katsarou-Katsari, A., Antoniou, C., & Theoharides, T. C. (2012). Quercetin is more effective than cromolyn in blocking human mast cell cytokine release and inhibits contact dermatitis and photosensitivity in humans. PloS one, 7(3), e33805. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033805

(19) Otsuka H, Inaba M, Fujikura T, Kunitomo M. Histochemical and functional characteristics of metachromatic cells in the nasal epithelium in allergic rhinitis: studies of nasal scrapings and their dispersed cells. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1995 Oct;96(4):528-536. DOI: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70297-0. PMID: 7560665.

(20) Horowitz, R.J. (2018). The Allergic Patient. Integrative Medicine, 4th Ed. Elsevier.

(21) Bone, K. & Mills, S. (2013). Principles and Practices of Phytotherapy. Elsevier Ltd.

(22) Hechtman, L. (2016). Clinical Naturopathic Medicine. Elsevier.

(23) Ramji D. Navapara, Devchand N. Avhad & Virendra K. Rathod (2011) Application of Response Surface Methodology for Optimization of Bromelain Extraction in Aqueous Two-Phase System, Separation. Science and Technology, 46:11, 1838-1847, DOI: 10.1080/01496395.2011.578101

(24) Seltzer AP. Adjunctive use of bromelains in sinusitis: a controlled study. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1967;46:1281–1288.

(25) Rathnavelu, V., Alitheen, N. B., Sohila, S., Kanagesan, S., & Ramesh, R. (2016). Potential role of bromelain in clinical and therapeutic applications. Biomedical reports, 5(3), 283–288. https://doi.org/10.3892/br.2016.720

(26) Ryan R.E. (1967). A double-blind clinical evaluation of bromelains in the treatment of acute sinusitis. Headache. 7:13 -7.

(27) Jamison J. (2003) Clinical Guide to Nutrition and Dietary Supplements in Disease Management. Churchill Livingstone.

(28) Braun, J. M., Schneider, B., & Beuth, H. J. (2005). Therapeutic use, efficiency and safety of the proteolytic pineapple enzyme Bromelain-POS in children with acute sinusitis in Germany. In vivo (Athens, Greece), 19(2), 417–421.

(29) Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. (2022). Allergic Rhinitis Clinical Update. www.allergy.org.au