Grant Hansen

(RCEP, CHEK Exercise Coach, CHEK Holistic Lifestyle Coach Level 1)

How much impact on the joints is dependent on factors such as the type of arthritis, which joints are affected, and how early the condition is managed.

What is arthritis?

Arthritis is a condition that can cause symptoms like inflammation, pain, swelling and stiffness in the joints.

This condition can vary in its impact on people from some slight symptoms and being manageable to reduced ability to do everyday tasks such as walking or going to work.

Arthritis refers to more than 100 different conditions that affect the joints, causing varying levels of joint damage, restricted movement, and pain.[2]

Arthritis refers to more than 100 different conditions that affect the joints

Globally, the most common form is osteoarthritis (OA), a degenerative joint disease that primarily affects older adults.

Living with arthritis can make everyday tasks more difficult due to pain, stiffness, or reduced mobility. The symptoms of arthritis can vary widely. For some, it has minimal impact and can be managed with medication and lifestyle strategies, while for others, it significantly affects independence and overall quality of life.[3,4,5,6]

In New Zealand, arthritis affects approximately 23.4% of people aged 15–64 and 64.4% of those over 65 years. Less common but still impactful forms include

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (0.4% population)

- Gout at (2.5% population)

- Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) affects approximately 0.12% of the New Zealand population. This estimate is based on around 9% of New Zealanders carrying the HLA-B27 gene, and about 1.3% of those carriers developing AS. While HLA-B27 is strongly associated with AS, a small proportion of people without this gene also develop the condition—estimated to be less than 0.01% of the general population

- Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) (0.2% population)[7]

- Reactive arthritis (0.6-27 per 100,0000)[8]

In the 2002/2003 New Zealand Health Survey found that 13.9% of men and 17.3% of women self-reported arthritis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or spinal disorders.[9]

Arthritis may result in having less strength, flexibility, balance, coordination, and cardiovascular fitness than people that are not active and live sedentary and don’t have arthritis, which negatively impacts their wellbeing and increases health risks.[5]

Despite the different medication options and stages of disease progression, exercise is considered to be a highly recommended part of managing arthritis across all types.[5]

Signs, symptoms and physical impact

Arthritis presents with a range of symptoms:

- Pain (either constant or intermittent) and may be sharp, dull or burning. Can be made worse with movement, not moving for a while or cold weather

- Stiffness (especially in the morning or after rest)

- Joint effusion (swelling)

- Synovitis (joint inflammation)

- Deformity (changes to joint shape due to damage and inflammation such as fingers being knobbly)

- Crepitus (joint noise or cracking)

These symptoms result in functional limitations and disability.[5]

Arthritis affects key physical capacities, including:

- Exercise tolerance (how much exercise/movement you can do before getting tired or sore)

- Muscle strength (reduced ability of your muscles to support your body such as carrying groceries)

- Aerobic capacity (reduced stamina to complete everyday tasks as well as exercise)

- Range of motion (ROM)

- Biomechanical efficiency (changes in movements that make tasks more challenging and potentially increasing fatigue or pain)

- Proprioception (reduced joint awareness increasing risk of losing balance and falling)

Joint pain comes from various sources such as ligament damage, increased intraosseous pressure (too much pressure inside the bone, often caused by swelling that can cause pain and make the joint feel stiff or sore), muscle weakness, or bursitis, and may be worsened by psychological factors like depression.

The damaged articular cartilage (smooth material at the end of your bones that acts like a shock absorber and prevents rubbing together) lacks nerves and blood vessels and doesn’t cause the pain directly.[5]

What are the common types of arthritis

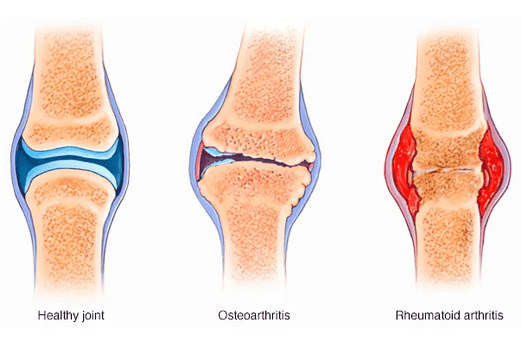

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, affecting approximately 40% of people with arthritis, while rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects approximately 20% of arthritis cases, and gout affects about 2.5% of the population.[7]

Osteoarthritis (OA)

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis and a leading cause of disability.

It is a degenerative joint disease characterized by the breakdown of articular cartilage and remodelling of subchondral bone (hard surface under the smooth cartilage).[4,5]

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis

This leads to symptoms such as joint pain, stiffness, crepitus (cracking or popping sounds from when part of the joint rubs together), and deformity.[4,5]

Exercise is very important for supporting OA and is considered the initial treatment option for OA.[10]

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

RA is an autoimmune, inflammatory disorder that primarily affects the synovial joints symmetrically. It causes pain, stiffness, joint deformity, and systemic effects like fatigue, muscle loss, and increased CVD risk.[5]

The most commonly affected joints are hands, feet, wrists, elbows and knees.

RA is more prevalent in women, with typical onset between 40–50 years.[5] It can result in varying degrees of symptoms such as pain and stiffness.

Gout

Gout is a type of arthritis that causes painful joint swelling and can also lead to kidney stones.

Symptoms may include pain, swelling, and redness of the skin over the affected joints. These signs occur when uric acid levels become too high in the blood.

Uric acid is a natural waste product formed when the body breaks down substances called purines, which are found in certain foods and drinks such as red meat, seafood, and alcohol.

Normally, uric acid dissolves in the blood, is filtered by the kidneys, and leaves the body through urine. However, when too much uric acid builds up, that can form sharp crystals in joints or kidneys, leading to either painful gout attacks or kidney stones.

Gout can have long-term effects if left untreated, including permanent joint damage, chronic kidney disease, kidney stones, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[11]

Gout can have long-term effects if left untreated

Gout is treatable, especially with the regular use of urate-lowering medicines.

Acute management

Medications prescribed by general practitioners (GPs) are used to manage gout flares when they occur.

Long-term prevention

Preventative strategies include urate-lowering medications such as allopurinol, which is the preferred choice for most patients. These options are typically discussed once gout is identified by your general practice team.

Lifestyle changes alone are not enough to prevent gout flares. A pharmacological approach is essential and should be supported by healthy habits. These may include:

- Avoiding known dietary or lifestyle triggers

- Maintaining a healthy diet

- Weight loss, if appropriate

Adherence to these urate lowering treatments is key. While it can be challenging, consistent daily use of the medication can prevent flares and reduce long-term complications.

Tracking serum urate levels over time helps to show progress and supports ongoing treatment. People with gout should also receive regular cardiovascular risk assessments and be monitored for other health issues such as chronic kidney disease and diabetes.

In New Zealand there are significant health inequities for Māori and Pacific peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand. In 2019 the prevalence of gout,compared with 4.7% of other New Zealanders, was:

- 8.5% of Māori

- 14.8% of Pacific peoples

These groups experience higher rates of gout, more severe disease, more frequent hospitalisations, and are often under-treated.[12]

Addressing these inequities requires culturally appropriate and accessible care.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS)

AS is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints.

It causes inflammation of ligaments that can lead to new bone formation, potentially in severe cases resulting in the fusing of the vertebrae (small bones that stack on top of each other to make your spine).

Unlike OA and RA, AS is more common in men, typically between 20 and 40 years old.

One of the key features of AS, that sets it apart, is that the symptom of back pain often improves with exercise and worsens at rest. This highlights the importance of physical activity in helping to manage this condition.[5]

The impact of arthritis on function and wellbeing. Arthritis doesn’t just affect joints, it impacts mental health, social connection, and overall quality of life.

Fatigue, reduced mobility, and pain may lead to social isolation, stress, and depression. Exercise plays a crucial role in breaking this cycle by improving physical capacity and enhancing social participation.

Māori women with OA reported that arthritis affected not just physical but also cultural and spiritual wellbeing.[13] This shows the wider impact on our lives and not just our physical health.

Who is at risk of arthritis?

Unmodifiable risks are:

- Older adults

- Female gender

- Maori & Pasifika men

- Previous joint injury

- History of sports

- Family history of arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, AS)

Modifiable risks are:

- Muscle atrophy and joint instability are common with OA, affecting function and independence.[5]

- Overusing our joints can increase our risk of developing arthritis. This is essentially putting more wear and tear which over time can lead to the cartilage being worn down. People at risk are runners or athletes from repetitive use, manual laborers that work with their hands or even musicians due to repetitive movements like lifting, bending or gripping things.[4]

- Being overweight and having a diagnosis of obesity (BMI of 30 kg/m² or higher). This increases the risk of developing arthritis particularly in the joints that weight bear such as knees, hips, and lower back due to additional pressure on these joints. This can result in increased wear and tear on the cartilage which cushions the bones. An example is getting more strain on your knees while walking or standing.[4]

- Smoking

- Not having enough exercise. Joints need appropriate loading for health. Both inactivity and excessive load can worsen symptoms.[5]

Three stages and symptoms of arthritis

Early or acute stage

What is it: This is a sudden increase in pain, stiffness and joint inflammation. Inflammation and mild joint symptoms that can be on and off in occurrence.

What it feels like: Pain and stiffness.

What to do: avoid aggravating activities, prioritise rest and gentle mobility exercises.

Intermediate or chronic stage

What is it: Symptoms that are persistent and joint degeneration that is progressive. This can result in loss of joint function.

What it feels like: Ongoing pain and stiffness.

What to do: maintain strength and aerobic capacity.

Late/severe stage with chronic with exacerbation

What is it: Significant joint damage, deformity, loss of mobility and disability.

What it feels like: Chronic pain.

What to do: similar to acute; rest and gentle movement until flare subsides.

Having support from a trained professional at each of these stages requires tailored exercise to maintain safety and maximise benefits. This can be from a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist.[5]

Physical activity in managing arthritis

Understandably people may want to avoid movement and activities that cause pain and fatigue resulting from arthritis. It is important to know that there is evidence that regular tailored exercise can reduce pain, improve function, and slow the progress of conditions such as OA.

When done safely, exercise and maintaining everyday activities is good for our joints and doesn’t cause further damage.[16,17]

Some of the benefits of exercise in arthritis management:

- Improve joint stability by strengthening the muscles around the affected joints

- Help with maintaining bone density as arthritis and inactivity often lead to bone loss

- Helps overall wellbeing and improves quality of life (mood, reducing anxiety and depression)[5]

We need to keep our joints mobile with a combination of aerobic, resistance and range of motion exercises and it is important that the exercise is suited to your level, starts slow and you have the knowledge to adapt exercise during flare ups.

While exercise plays a significant role in both prevention and management of arthritis, making an appointment with your general practice teams to discuss your symptoms can help firstly to identify and support you in managing your condition long term.

Grant is a registered Clinical Exercise Physiologist (CEP) and Holistic Lifestyle Coach. He has over 15 years of experience of working in New Zealand within the primary healthcare sector. After completing a Sports Science degree, Grant started working in the gyms around the North Island and was a Personal Trainer in Sydney…

If you would like to learn more about Grant see Expert: Grant Hansen.

References

(1) Cleveland Clinic. (2023). Arthritis: Overview and More. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/12061-arthritis

(2) Arthritis New Zealand. (n.d.). What is Arthritis? Retrieved from https://www.arthritis.org.nz/what-is-arthritis/

(3) Reveille, J. D. (2011). The genetic basis of ankylosing spondylitis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 23(4), 332–339.

(4) Arthritis Foundation. (n.d.). Understanding Arthritis.

(5) Ehrman, J.K., Godon, P.M., Visich, P.S., & Keteyian, S.J. (2013). Clinical Exercise Physiology (3rd ed.). Human Kinetics.

(6) Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Arthritis: Symptoms and Causes. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/arthritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350772#dialogId56280893

(7) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Arthritis Basics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/index.html

(8) Chakraborty, R. K., Cheeti, A., & Ramphul, K. (2025). Reactive arthritis. In StatPearls. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499831/

(9) Ministry of Health NZ. (2006). A Portrait of Health – Key results of the 2023/2024 New Zealand Health Survey. Retrieved from https://thehub.sia.govt.nz/resources/a-portrait-of-health-key-results-of-the-200203-new-zealand-health-survey?utm_source=chatgpt.com

(10) Płaszewska-Żywko, L., Marcinkiewicz, A., & Płaszewski, M. (2023). Risk factors for osteoarthritis and the impact of early diagnosis and management: A review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4247.

(11) bpacnz. (2025). Managing gout: Best practice for diagnosis and long-term treatment. Retrieved from https://bpac.org.nz/2025/gout.aspx

(12) Te Karu, L., Bryant, L., Elley, C. R., & Garrett, S. (2021). Achieving health equity in gout: The importance of culturally safe care. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 114(9), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X211028007

(13) McGruer, N., Baldwin, J. N., & Ruakere, B. T. (2021). The lived experience of osteoarthritis in Māori and non-Māori older adults in New Zealand. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 36, 171–187.

(14) Deloitte Access Economics & Arthritis New Zealand. (2018, September). The economic cost of arthritis in New Zealand in 2018. Retrieved from https://www.arthritis.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Economic-cost-of-Arthritis-in-New-Zealand-2018.pdf

(15) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Arthritis risk factors. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/risk-factors/index.html

(16) American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). (2020). Exercise and arthritis.

(17) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2022). Osteoarthritis in over 16s: Diagnosis and management (NG226). Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226