Zohreh Doborjeh

(PhD (Cognitive Neuroscience), BS and MS (Psychology), Cert (Neuroinformatics), Certified Mindfulness Facilitator)

Mental exercise refers to activities that engage and stimulate the brain, helping to improve brain function and overall mental agility. Similar to physical exercise, which strengthens muscles and enhances physical health, mental exercises

- encourage the growth of neural connections

- enhance mental clarity and vitality

- build cognitive resilience over time[1]

Mental exercises can take various forms, such as puzzles, learning new skills, memory games, problem-solving tasks, creative activities like writing or playing a musical instrument, and others.

The Connection Between Mental Activity and Brain Health

Mental exercises stimulate neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. This process is key to maintaining cognitive function as we age,

- delaying cognitive decline

- enhancing memory

- enhancing attention

- enhancing problem-solving skills[2]

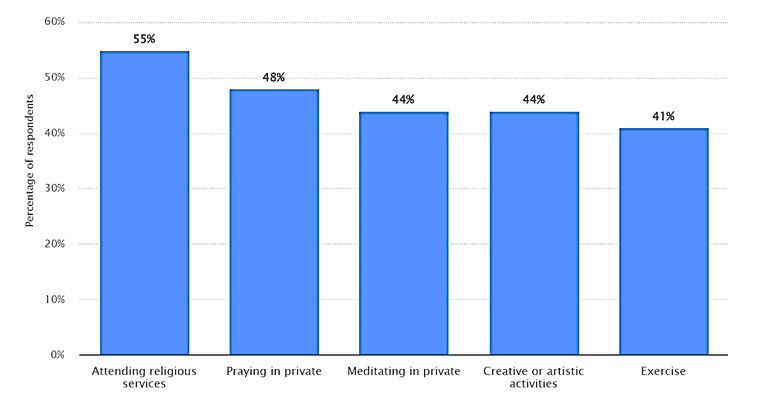

Mental activities can differ widely across individuals and cultures, influenced by personal beliefs, values, and practices. For example, a study conducted in the U.S. found that older adults considered praying to be the most effective activity for maintaining or improving brain health.

This could be because prayer often involves deep reflection, emotional comfort, and a sense of connection, all of which can reduce stress, lift up our mood, and sharpen our mind.

Mental exercises stimulate neuroplasticity

Such calming practices highlight the importance of a serene mind for a healthy brain, demonstrating that mental exercises like mindfulness and meditation can greatly contribute to overall mental resilience and well-being.[3]

In this article, we introduce some of the most effective mental activities that can support a healthy brain, calm the mind, help prevent mental diseases, and slow down cognitive decline over time.

These practices are divided into 3 main categories, which are

- brain stimulating activities

- brain soothing activities

- brain adaptive activities

These benefits are supported by scientific studies, highlighting the crucial role of mental engagement in maintaining cognitive function and overall brain health.

Brain Stimulating Activities

Stimulating brain activities are designed to challenge different brain functions crucial for mental agility and well-being. Stimulating mental exercises go beyond traditional word games to activate various cognitive functions like memory, concentration, and attention.

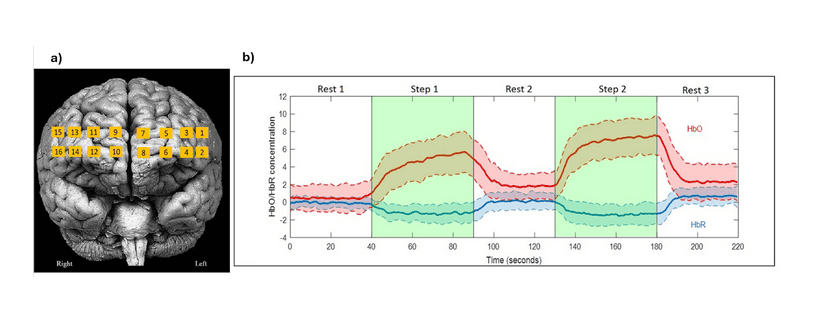

Studies showed that Sudoku and crossword puzzles enhance problem-solving, memory, and cognitive flexibility. A 2020 study found increased prefrontal cortex (PFC) activity during Sudoku, measured via oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and deoxyhemoglobin (HbR) levels.

This highlights Sudoku’s potential in cognitive remediation therapy, improving working memory, attention, and decision-making.[4]

a) Brain measurement: 16 optode positions are shown on the brain surface (frontal view).

b) The solid red and blue lines represent the grand average concentrations of HbO (oxygenated hemoglobin) and HbR (deoxygenated hemoglobin) across all optodes during the task, respectively.

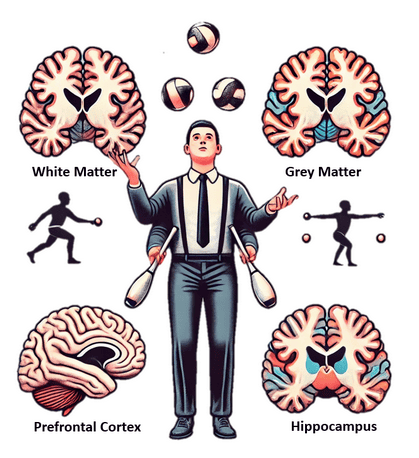

On the other hand, coordination-based activities such as learning to juggle has been shown to enhance brain plasticity and lead to positive structural changes, particularly in the grey matter (GM) of the hMT/V5 area, as well as in white matter (WM) density.

Studies indicate that experienced jugglers demonstrate more developed brain structures compared to non-jugglers, especially in regions associated with motor learning and visual processing.[5]

In this study, Voelcker-Rehage and Willimczik investigated motor plasticity in a juggling task across 1,206 participants aged 6 to 89 years. The study found that older adults significantly improved their juggling performance after just six training sessions.

Their post-training performance levels became comparable to children aged 10–14 years and younger adults aged 30–59 years. Only participants aged 15–29 years had significantly higher baseline and post-training performances. These findings highlight the brain’s lifelong ability to learn new motor skills, emphasising the plasticity of neural networks even in older age through stimulation activities.[5]

Moreover, juggling activates the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampus, both crucial for attention and memory. A recent research showed that longer-duration juggling practice is associated with greater increases in grey matter volume, reinforcing the cognitive benefits of motor skill learning.[6]

The activity engages and strengthens multiple brain areas, including the grey matter (responsible for motor coordination), white matter (enhancing communication between brain regions), prefrontal cortex (supporting decision-making and focus), and hippocampus (boosting memory and spatial awareness).

Another stimulating activity is board games like chess that activate multiple brain regions simultaneously, including those responsible for planning, attention, and visual-spatial abilities.[7]

A neuroimaging study by Hänggi et al. (2014) compared 20 expert chess players with 20 controls, revealing distinct structural adaptations in the brains of experienced players. The chess players had

- 15% reduction in grey matter volume and decreased cortical thickness in the occipitotemporal junction (OTJ), which is a region critical for object recognition and pattern processing

- 10% reduction in the precuneus, an area linked to visual-spatial and attentional control

These findings suggest neural pruning, where unnecessary connections are eliminated to optimise cognitive function.

White matter adaptations were also evident, with a 5% increase in mean diffusivity in the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), a major white matter tract connecting the parietal and frontal lobes.

These structural changes suggest enhanced neural efficiency and faster decision-making, indicating that higher-ranked players exhibit more streamlined neural networks, supporting superior attention, memory, and cognitive flexibility.

The findings suggest that long-term chess practice enhances cognitive efficiency through neuroplasticity rather than increasing brain volume.

Brain Soothing Activities

Brain soothing activities are designed to

- calm the mind

- reduce mental fatigue

- improve emotional resilience

- alleviate stress

- enhance overall cognitive well-being

There are various ways to integrate brain-soothing practices into daily life, but here we highlight three main approaches.

Positivity and affirmation

Engaging in positive self-talk and affirmations can enhance the brain functions. Research by Cascio et al. (2016) shows that future-oriented affirmations (those focused on positive goals and upcoming experiences) activate brain regions related to reward and self-processing, such as the ventral striatum (VS) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC).

These changes were linked to reduced sedentary behaviour and increased motivation. When examining future-oriented value scenarios, affirmed participants showed significantly greater activity in the valuation network (13.3% increase) compared to controls (-2.9%). They also had higher activity in the self-processing network (14.7% vs. 4.8%).

Future-oriented affirmations engage areas like the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), highlighting their role in enhancing emotional resilience and motivation.[8]

While future-oriented affirmations are powerful for inspiring change, present-moment affirmations also play a crucial role in calming the mind and self-acceptance.

Present-moment affirmations, especially when grounded in mindfulness and self-compassion, engage the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) that are important areas in the default mode network (DMN), which is linked to self-reflection, emotional regulation, and internal awareness.[9]

Journaling and gratitude

Journaling is the practice of regularly writing down thoughts, emotions, and reflections to help process experiences, clarify thoughts, and gain insights into personal growth.

Gratitude journaling, in particular, has been shown to activate the hypothalamus, which regulates stress levels and promotes overall well-being.

Gratitude expression was also linked to activity in the parietal and lateral prefrontal cortex, especially the intraparietal sulcus and inferior frontal gyrus, areas involved in mental arithmetic. The pregenual anterior cingulate cortex also showed increased activity related to gratitude, aligning with empathy and moral cognition.[10]

In this study, Kini et al. (2016) found that participants who completed three sessions of gratitude letter writing reported a significantly greater increase in gratitude levels (+1.27 vs. +0.06; t(40) = 2.25, p = 0.015) compared to a control group. During a “Pay It Forward” task in an fMRI scanner three months later, these participants donated an average of 60.5% of their endowments and showed significantly increased activation in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex.

This finding highlights the lasting effects of gratitude journaling on brain areas involved in empathy, moral reasoning, and emotional regulation.[10]

Meditation and mindfulness

Meditation involves a set of techniques designed to train the mind, often through focused attention, deep breathing, or guided imagery, with the goal of improving calmness, concentration, and self-awareness.

Mindfulness, a key component of meditation, refers to the practice of being fully present and aware of one’s thoughts, feelings, and surroundings without judgment.[11]

One study on mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) found that eight weeks of training led to a 27% reduction in amygdala activation, correlating with lower anxiety and improved emotional stability. Additionally, long-term meditators show a thicker ACC, which is linked to better emotional control and resilience.[12]

RELATED — Introduction to Anxiety: Know what you are dealing with (Part 1)

Furthermore, mindfulness reduces amygdala hyperactivity, dampening the intensity of negative emotions like fear and anxiety.

Another study found a 40% decrease in amygdala reactivity after mindfulness training, indicating its potential to promote emotional balance and psychological well-being.

Brain Adaptive Activities

Brain adaptive activities refer to acquiring new knowledge or mastering new skills that lead to reactivating brain plasticity and supporting slowing the brain decline over time and age.

For example, learning a musical instrument activates multiple brain regions involved in auditory processing, motor control, and memory.[13]

A study by Corbett. et al (2024) analyzed data from over 1,100 adults aged 40+ and found that those who played a musical instrument scored up to 24% higher on working memory tasks and 17% higher on executive function tests compared to non-musicians. The strongest effects were seen in people who continued playing into older age, especially keyboard players.[14]

Also, studying a new language will enhance cognitive abilities such as attention, memory, and multitasking. Studies indicate that bilingualism delays the onset of cognitive decline and improves executive function due to increased neural efficiency and cognitive reserve.[15]

High-proficient bilinguals scored significantly higher on creative thinking tests, 60% better on convergent thinking (p = .003) and over 40% better on cognitive flexibility tasks (p = .017), showing how bilingualism sharpens both focus and flexibility in problem-solving.[16]

Research showed that taking up a new hobby and engaging in activities like painting, gardening, and cooking that require learning new techniques and skills promotes brain health. These activities enhance creativity, problem-solving skills, and can provide a sense of accomplishment, all of which are beneficial for cognitive function.[17,18,19]

If you are just joining us, we suggest reading Brain Health and Exercise: Physical Exercise.

Zohreh is a Senior research fellow and lecturer, holding Master’s and Bachelor’s degrees with Honors in Psychology, and a Ph.D. in Cognitive Neuroscience. She has eight years of research and teaching experience in the subjects of psychology, neuroscience, and Neuroinformatics across different universities in New Zealand, including the University of Auckland, Auckland University of Technology, and The University of Waikato.

If you would like to learn more about Zohreh , see Expert: Zohreh Doborjeh.

References

(1) Churchill, J. D., Galvez, R., Colcombe, S., Swain, R. A., Kramer, A. F., & Greenough, W. T. (2002). Exercise, experience and the aging brain. Neurobiology of aging, 23(5), 941-955.

(2) Kays, J. L., Hurley, R. A., & Taber, K. H. (2012). The dynamic brain: neuroplasticity and mental health. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 24(2), 118-124. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12050109

(3) Vankar, P. (2023, November 29). Older U.S. adults’ most effective brain-stimulating activities 2017. Published by Statista.

(4) Ashlesh, P., Deepak, K. K., & Preet, K. K. (2020). Role of prefrontal cortex during Sudoku task: fNIRS study. Translational neuroscience, 11(1), 419-427. https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/tnsci-2020-0147/html

(5) Voelcker-Rehage, C., & Willimczik, K. (2006). Motor plasticity in a juggling task in older adults—a developmental study. Age and ageing, 35(4), 422-427.

(6) Malik, J., Stemplewski, R., & Maciaszek, J. (2022). The effect of juggling as dual-task activity on human neuroplasticity: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7102. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9222273/

(7) Hänggi, J., Brütsch, K., Siegel, A. M., & Jäncke, L. (2014). The architecture of the chess player׳ s brain. Neuropsychologia, 62, 152-162.

(8) Cascio, C. N., O’Donnell, M. B., Tinney, F. J., Lieberman, M. D., Taylor, S. E., Strecher, V. J., & Falk, E. B. (2016). Self-affirmation activates brain systems associated with self-related processing and reward and is reinforced by future orientation. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 11(4), 621-629. https://academic.oup.com/scan/article/11/4/621/2375054

(9) Farb, N. A., Segal, Z. V., & Anderson, A. K. (2013). Mindfulness meditation training alters cortical representations of interoceptive attention. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 8(1), 15-26. https://academic.oup.com/scan/article/8/1/15/1696050

(10) Kini, P., Wong, J., McInnis, S., Gabana, N., & Brown, J. W. (2016). The effects of gratitude expression on neural activity. NeuroImage, 128, 1-10.

(11) Wheeler, M. S., Arnkoff, D. B., & Glass, C. R. (2017). The neuroscience of mindfulness: How mindfulness alters the brain and facilitates emotion regulation. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1471-1487.

(12) Taren, A. A., Gianaros, P. J., Greco, C. M., Lindsay, E. K., Fairgrieve, A., Brown, K. W., … & Creswell, J. D. (2015). Mindfulness meditation training alters stress-related amygdala resting state functional connectivity: a randomized controlled trial. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 10(12), 1758-1768. https://academic.oup.com/scan/article/10/12/1758/2502572

(13) ENHANCER, M. A. A. M. (2018). Keep your brain young with music: Insights from machine learning and brain imaging. Innovation in Aging, 2(S1), 849.

(14) Vetere, G., Williams, G., Ballard, C., Creese, B., Hampshire, A., Palmer, A., … & Corbett, A. (2024). The relationship between playing musical instruments and cognitive trajectories: Analysis from a UK ageing cohort. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 39(2), e6061. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/gps.6061

(15) Berkes, M., Calvo, N., Anderson, J.A., Bialystok, E., and Initiative, A.s.D.N.: ‘Poorer clinical outcomes for older adult monolinguals when matched to bilinguals on brain health’, Brain Structure and Function, 2021, 226, pp. 415-424

(16) Xia, T., An, Y., & Guo, J. (2022). Bilingualism and creativity: Benefits from cognitive inhibition and cognitive flexibility. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1016777. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1016777/full

(17) Lentoor, A.G.: ‘Effect of gardening physical activity on neuroplasticity and cognitive function’, Exploration of Neuroprotective Therapy, 2024, 4, pp. 251-272. https://www.explorationpub.com/Journals/ent/Article/100481

(18) Saavedra-Macías, F.J., Arias-Sánchez, S., and Rodríguez-Gómez, A.: ‘Painting as a Tool to Promote Health and Well-Being: Rationale and Empirical Evidence’: ‘Painting’ (Emerald Publishing Limited, 2023), pp. 17-35

(19) Farmer, N., Touchton-Leonard, K., and Ross, A.: ‘Psychosocial benefits of cooking interventions: a systematic review’, Health Education & Behavior, 2018, 45, (2), pp. 167-180