Will Simcock

BSc (Hons) Neuroscience

Eating disorders are complex mental health conditions characterised by disturbances in eating behaviours and related thoughts and emotions.

Bulimia nervosa can occasionally be mistaken for other eating disorders due to shared symptoms and features, although there are distinct differences.

This article will cover the general presentation of bulimia nervosa, its signs, symptoms, and how to spot it in those around you.

What is Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia Nervosa is an eating disorder that impacts individual eating habits as well as their feelings towards food and their personal image.

Bulimia is characterised by cycling between periods of frequent binge eating, followed by purging and compensatory behaviours in an attempt to avoid weight gain.

Most commonly arising in adolescence and early adulthood bulimia can affect people from all walks of life.[1]

Unfortunately, there is a stereotype that bulimia only impacts young women which can prevent other people from getting the help they need.

Overview of bingeing and compensatory behaviours

Binge eating is generally defined as eating a larger amount of food than would normally be consumed in the same amount of time.

This can look very different from person to person however, dependent on their usual eating habits and how the disorder manifests. Cultural differences can also impact how binge episodes present.

Binge eating episodes are accompanied by a feeling of loss of control over the individuals eating and an inability to stop themselves. For teenagers and young adults binging on high calorie foods that they would typically avoid is common, often consuming low calorie foods and adhering to a “diet” in between episodes.[2]

RELATED — Binge Eating disorder: Is it a mental illness or an excuse to overeat?

This cycle is increasingly common with the rise of fitness culture and ‘fitspiration” content flooding youth social media feeds.

These binge eating episodes are typically followed by purging – behaviours intended to compensate for excessive eating to prevent any weight gain. These are typically represented in the media as self-induced vomiting, although can also include other methods like fasting.[3]

Accompanying the fluctuation between binge eating and purging is a strong focus on weight and shape, as well as low self-esteem.

Many individuals often feel deeply dissatisfied with their body and appearance, frequently thinking or talking about losing weight or fearing gaining weight.[4]

Diagnostic criteria

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V) lists the following diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa.[4]

Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode is characterised by the following:

- Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g., within a 2-hour period), an amount of food that is larger than what most people would eat during a similar period of time under similar circumstances

- Lack of control overeating during the episode (e.g., feeling that you cannot stop eating, or control what or how much you are eating).

Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviour to prevent weight gain, such as but not limited to self-induced vomiting.

The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviours both occur, on average, at least once a week for three months.

Self-evaluation is overly influenced by body shape and weight.

Binging or purging does not occur exclusively during episodes of behaviour that would be common in those with anorexia nervosa.

Distinction from other eating disorders

Bulimia nervosa can occasionally be mistaken for other eating disorders due to shared symptoms and features, although there are distinct differences.

Unlike Anorexia nervosa, where individuals typically have a marked reduction in body weight (compared to normal) due to intense food restriction, people with bulimia nervosa often maintain a relatively stable weight.[5]

This is due to the cycling between bingeing and purging and can make bulimia harder to recognise from the outside due to the stereotype of eating disorders making you underweight.[3]

RELATED — Understanding Eating Disorders: History, Types and Statistics

Binge eating disorder (BED) also involves binge eating episodes and feelings of loss of control overeating habits. Except unlike bulimia, this is not paired with regular purging and compensatory behaviours such as vomiting or excessive exercise.[4]

Due to these overlapping symptoms, if you are concerned about your own health or a loved one, a professional diagnosis is crucial to ensure the correct treatment and support is provided.

Signs and symptoms

Bulimia nervosa is a difficult disorder to identify, as individuals tend to maintain weight within a normal range. The disorder is frequently overlooked, both by those experiencing it and those they are surrounded by.

As aforementioned, a core feature of BN is the repetitive cycle of binge eating

- the consumption of large amounts of food in a short period

- followed by compensatory behaviours like self-induced vomiting or excessive exercise[4]

These behaviours tend to be accompanied by a strong focus and obsession with body shape and weight, combined with feelings of low self-esteem.[2] Many people with BN also feel guilt and shame about their habits and will eat in secret or avoid others, often due to embarrassment.[3]

Physical signs of BN may include

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Digestive disturbances

- Food avoidance

- Compensatory behaviours

These can manifest in different ways in different people and thus it is important to pay attention to even small changes.[3]

These signs are typically not very visible or easily recognised. This makes it crucial to pay close attention to the mood, behaviour, and eating patterns of anyone you think could be dealing with BN.

Early recognition and treatment are critical to ensure access to the necessary support and improve recovery outcomes.

Prevalence and demographics

Eating disorders are rather common in New Zealand, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) Mental Health study reporting lifetime rates of Bulimia nervosa at 1.3%.[6,7]

Lifetime rates of Bulimia nervosa are 1.3%

The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (Te Rau Hinengaro) reported similar rates with national prevalence rates of 1.3% and noted higher rates of eating disorders for Māori and Pacific Peoples compared to the rest of the sample.[8,9]

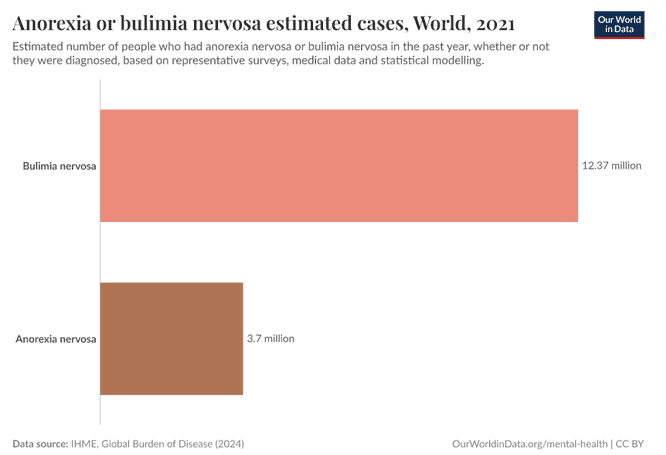

This translates to more than 62,000 people in New Zealand that have experienced Bulimia Nervosa at some stage of their lives, making it more common than Anorexia nervosa.[9]

Both men and women experience disturbances in body image, disordered eating, and unhealthy/obsessive weight-control behaviours.[10]

Importantly, eating disorders are often under-diagnosed in men, partly due to lingering stigma and societal stereotypes.

Research suggests that binge eating, and compensatory behaviours may occur at similar rates in men as in women, and unhealthy weight control practices may be increasing at faster rates among men.[11]

Conclusion

Bulimia nervosa is a complex and often misunderstood eating disorder. Due to its variation in presentation and lack of marked weight change it can easily go amiss by those experiencing it and those around them.

It is important to recognise the signs, including cycles of binge eating and purging behaviours, accompanied by strong concerns about body image and weight. This is an important first step to getting the necessary help.

With early intervention and the correct treatment recovery is very achievable.

In the following parts of this series, we will explore the root causes of bulimia nervosa and the physical and emotional consequences that accompany it when left untreated.

References

(1) EDGI. (2024, December). About eating disorders – EDGI. EDGI. https://edgi.nz/about-eating-disorders/

(2) Brownell, K. D., & Fairburn, C. G. (2002). Eating disorders and obesity : a comprehensive handbook, 2nd ed. The Guilford Press.

(3) What Is Bulimia Nervosa? – Child Mind Institute. (2025, January 31). Child Mind Institute. https://childmind.org/article/what-is-bulimia-nervosa/#symptoms-of-bulimia-nervosa

(4) Feltner, C., Peat, C., Reddy, S., Riley, S., Berkman, N., Middleton, J. C., Balio, C., Manny Coker-Schwimmer, & Jonas, D. E. (2022, March). Appendix A Table 1, Summary of DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders. Nih.gov; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Appendix A Table 1, Summary of DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders

(5) Russell, G. (1979). Bulimia nervosa: an ominous variant of anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 9(3), 429–448.

(6) Anorexia or bulimia nervosa estimated cases. (2025). Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/anorexia-bulimia-nervosa-estimated-cases

(7) Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P. A., Chiu, W. T., Deitz, A. C., Hudson, J. I., Shahly, V., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Benjet, C., Bruffaerts, R., Girolamo, G. de, Graaf, R. de, Haro, J. M., Viviane Kovess-Masfety, O’Neill, S., Posada-Villa, J., Sasu, C., Scott, K., & Viana, M. C. (2013). The Prevalence and Correlates of Binge Eating Disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73(9), 904–914.

(8) Lawson, R., Watterson, R., Kennedy, M. A., Bulik, C. M., & Jordan, J. (2024). Time taken to reach treatment for eating disorders in New Zealand. Australasian Psychiatry.

(9) Oakley, M. A., Wells, J. E., Scott, K. M., & Mcgee, M. A. (2006). Lifetime Prevalence and Projected Lifetime Risk of DSM-IV Disorders in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(10), 865–874.

(10) Mitchison, D., & Mond, J. (2015). Epidemiology of eating disorders, eating disordered behaviour, and body image disturbance in males: a narrative review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0058-y

(11) Strother, E., Lemberg, R., Stanford, S. C., & Turberville, D. (2012). Eating Disorders in Men: Underdiagnosed, Undertreated, and Misunderstood. Eating Disorders, 20(5), 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.715512