Carly Hanna

BSc (Human Nutrition and Psychology)

Note — The article was checked and updated April 2023.

Jump to:

Many of us find that we sometimes overeat, because there’s “always room for that dessert”. While we may have eaten more than we usually would in one sitting, is this considered a binge?

Binge eating disorder involves regularly consuming large quantities of food in a short amount of time and not being able to control this eating behavior. It is the most common eating disorder in New Zealand and worldwide.

How do we know when eating patterns like binge eating start to interfere with our daily lives, and how do we know if it’s a disorder or if it’s all in our head?

There are several personal, genetic and environmental factors that contribute to the risk of developing a binge eating disorder.

Let’s take a bite into it, and see how to recognise binge eating and tips to control it.

What is a binge eating disorder?

Binge eating, or compulsive eating, is an eating disorder characterized by eating a large portion of food in a discrete period of time as well as having a lack of self control over eating during the episode.

Binge eating disorder also has a high prevalence of comorbid anxiety and/or depression and feelings of shame and guilt.

It can also include symptoms such as

- Compulsions over the urge to eat (which can’t be controlled)

- Anosognosia (being unaware or “in denial” of an illness)

- Yo-yo dieting (cycling between restricting food and then binging food)

Diet culture contributes to the increase of eating disorders

There are many misconceptions about eating disorders, a few that will be addressed in this article.

Anyone can develop an eating disorder, regardless of age, gender, health, weight, socio-economic and cultural groups.[1]

RELATED — Understanding Eating Disorders: History, Types and Statistics

Eating disorders can occur from a variety of factors such as psychological (how we think), biological (body anatomy), genetic (hereditary factors), cultural (values and beliefs), and social (relationships with others).[2]

History of binge eating disorder

Binge eating was first recognised in literature in 1959. It was referred to as night eating syndrome as people would often binge eat in the middle of the night. However, it was soon realized that this eating behavior can occur at any time of day.[3]

In the 1980’s, binge eating was mentioned in the features of bulimia nervosa in the DSM-III, but not yet as its own classification. This raised awareness around the behavior, but not recognition as an eating disorder itself.

In 1994, binge eating was referred to as EDNOS (eating disorder not otherwise specified) which meant people struggled to get treatment as it wasn’t recognised as an independent disorder. This was different to anorexia nervosa, which was considered a psychological disorder in the DSM-I.[4]

A nonprofit organization called BEDA (binge eating disorder association) was formed in 2008 in support and advocacy for the binge eating community.

Binge eating disorder finally received diagnostic criteria in the DSM-V (diagnostic statistics manual, 5th edition) in 2013.

Symptoms and signs of binge eating disorder

DSM-V diagnosis includes five points:

- Recurrent episodes of binge eating (eating a large portion of food in a discrete period of time as well as a lack of self control over eating during the episode)

- Binge eating episodes are associated with 3+ symptoms (explained further)

- Binge eating occurs at least once a week for 3 months, on average

- Binge eating is not associated with compensatory behaviors (i.e. purging, excessive exercise)

- Does not meet criteria for other eating disorders (such as bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa, or other eating conditions not elsewhere classified)

Symptoms of binge eating

Eating faster than normal

Eating food faster than considered normal can look like not chewing food as much and potentially scoffing it down.[5]

RELATED — A Guide to Mindful Eating

Eating until uncomfortably full

We are all born with innate hunger/satiety cues, though these can be disrupted in those with eating disorders.

When binge eating, one can receive signals from the body that they are full, but continue to eat past these cues.[5]

Eating large amounts of food when not physically hungry

Like satiety, hunger cues can also be dampened or ignored. In terms of binge eating, people will eat regardless of whether they are hungry or not.[6]

RELATED — The Ultimate Guide to Intuitive Eating (with steps)

Eating alone due to embarrassment

During a binge episode a lot more food is eaten in one sitting when compared to the average person.

That is why those who binge eat often experience intense embarrassment and don’t like to eat around others.[6]

Feelings of shame, depression, guilt, or disgust

Along with embarrassment and feelings of shame, guilt and disgust can also present in those with a binge eating disorder. These emotions can lead to depressive behavior which can create a vicious cycle of eating in response to strong emotions.[6]

Distress about binge eating behavior

Binge eating episodes can interfere with one’s daily life, especially in terms of social setting. This can cause the affected person immense distress.[5]

Severity (how many binge eating episodes occur per week).[5]

Mild: 1-3 times a week

Moderate: 4-7 times a week

Severe: 8-13 times a week

Extreme: 14+ times a week

RELATED — Understanding Stress: The Silent Killer

Prevalence of binge eating disorder

While there is no binge eating specific NZ data, the prevalence in New Zealand is believed to be slightly higher than 1% of the population – which is higher than bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa and other specified feeding or eating disorders.[1]

Worldwide, approximately 3% of the US adult population have a binge eating disorder.[5]

In the UK, around 1.25 – 3.4 million people are affected by an eating disorder, with about half meeting criteria for a binge eating disorder.[7]

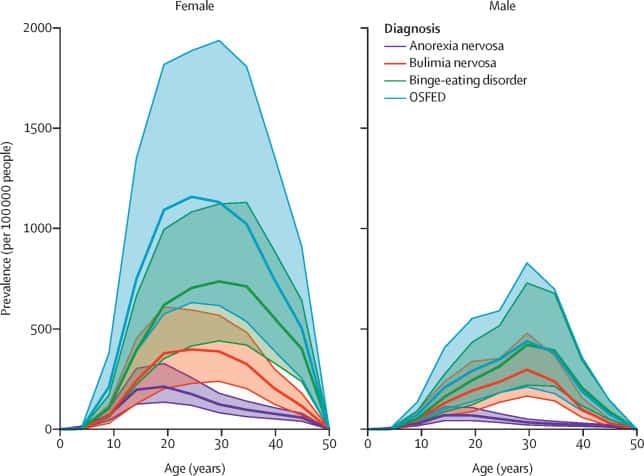

As seen in the graph below, males and females have a more equal prevalence with a binge eating disorder compared to other eating disorders. The age of onset can vary widely, but mainly peaks around 20-30 years of age.[8]

Source: Melen, S., The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (The Lancet 2021).

It is common for people with a binge eating disorder to have mental health comorbidities such as

- Depression

- Anxiety

- OCD

- PTSD

The mortality rate from binge eating disorder is unknown.

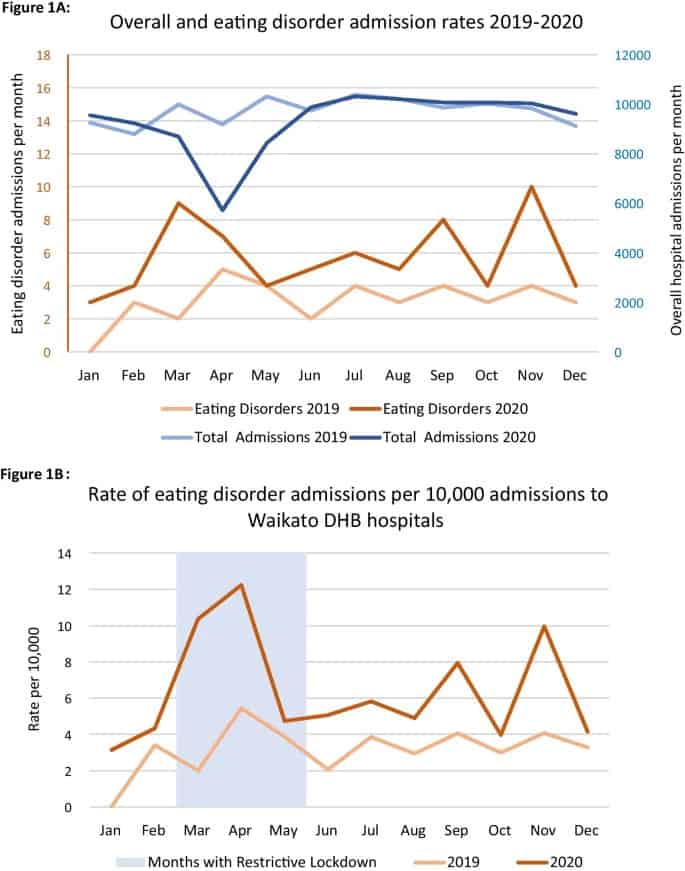

The COVID-19 pandemic has also increased the risk of eating disorders, including a binge eating disorder. Auckland’s Starship Children’s Hospital and Auckland City Hospital’s eating disorder admissions doubled from 2020 to 2021.[9]

The pandemic responses, especially lockdowns, have changed people’s routines/lifestyles and have also increased social isolation and anxiety.

This can be triggering for those who struggle with their eating behaviors, and also put more people at risk of developing a binge eating disorder.[9]

Risk factors for developing a binge eating disorder

There are several risk factors that can contribute to developing an eating disorder. This can include psychological, sociocultural or genetic factors, as explained further below.

Genetics and family history, and binge eating

Much like any physical illness, mental health conditions can also have a genetic component.

If there is a family history of

- Eating disorders

- Depression

- Alcohol / drug misuse

this can increase the risk of developing a binge eating disorder.[10]

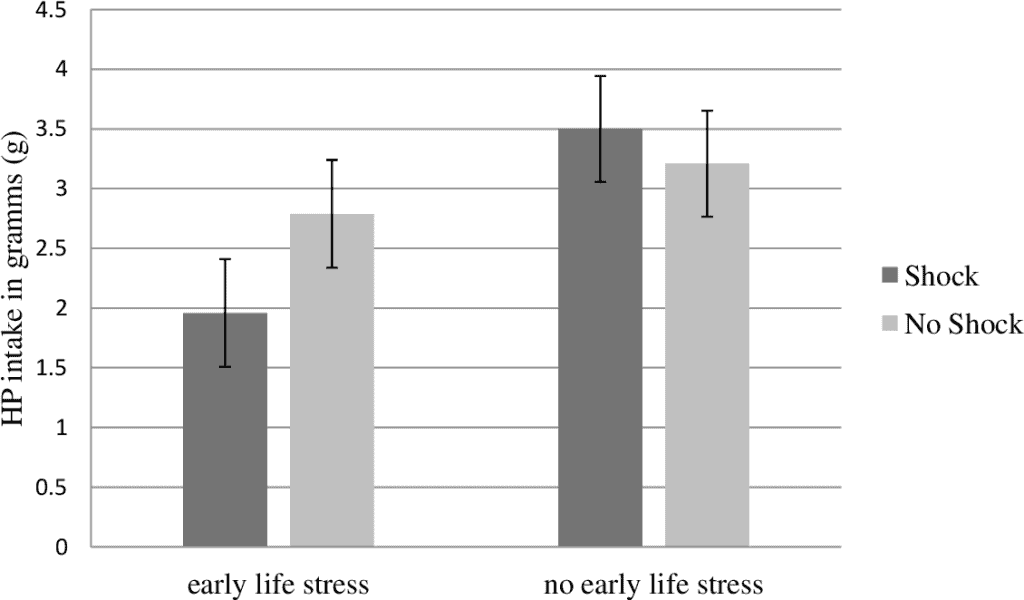

Connection between stress and binge eating

Source: Sinclair, A., The effects of early life stress on stress induced binge eating later in life. (Submitted for the requirement for the degree of Honours Bachelor of Arts in Psychology).

Mental health comorbidities and relation to binge eating

Common mental health comorbidities that often happen with eating disorders are anxiety, depression and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

This is because some symptoms overlap – such as increased anxiety of eating around others, feelings of guilt and shame and compulsions over certain behaviors.[10]

Perfectionistic traits and binge eating

Having high standards and expectations can lead to a high level of self-awareness, which is often accompanied by distress, anxiety, and/or depression.

Those who have aversive self perceptions will focus on one stimulus (eg. food and binge eat to gain a sense of control).[12]

Other psychological causes

Other psychological factors, such as impulsive behavior, low self-esteem, and concern with body shape and weight can increase the risk of a binge eating disorder.[10]

Dieting and food restriction, and how it affects binge eating

Restricting our food intake by dieting / starvation is one of the leading causes of binge eating.

If we have restricted our body of energy (calories), it is our body’s intuition to regain enough calories in order to survive. This is why we might have the compulsions to eat, after being restricted of food for certain periods of time.[5,11]

Body-image perception

If we constantly receive messages from others, or even the media, about our weight and health, this is naturally going to lower self-esteem.

This can lead to increased thoughts of our own body shape, weight, or eating habits, which can lead to unhealthy behaviors, such as restricting and binge eating.[10]

Sociocultural factors

As mentioned previously, sociocultural factors such as diet culture and fat phobia can contribute to an increased prevalence of eating disorders.

While several diet-related diseases are associated with obesity, it is important to remember that weight is not an accurate reflection of health.[5,11]

RELATED — What is Health at Every Size (HAES): Does it promote obesity and is it healthy?

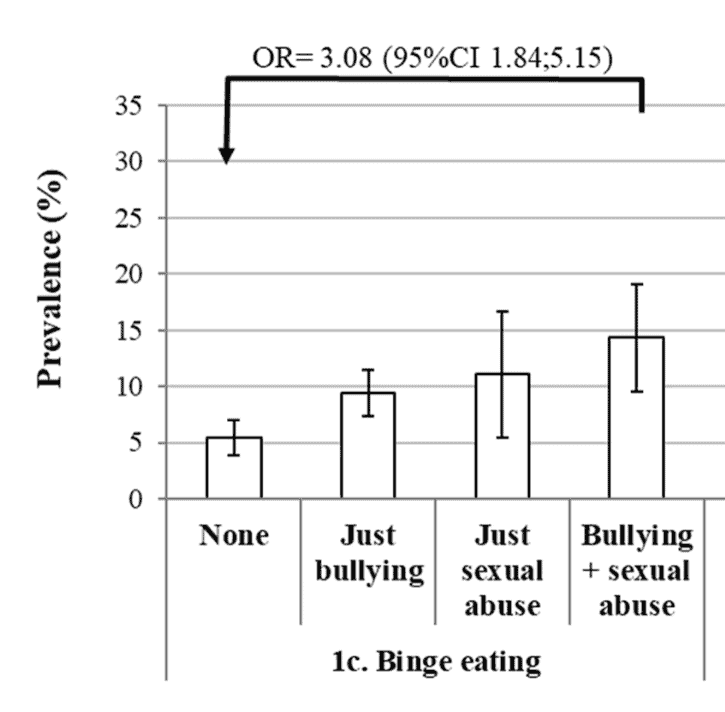

Sexual abuse and binge eating

People with a history of sexual abuse are more likely at risk of developing a binge eating disorder.[10]

Source: Bowden, J., Bullying and sexual abuse and their association with harmful behaviours, antidepressant use and health-related quality of life in adulthood: a population-based study in South Australia (BMC Public Health, 2019)

Effects of binge eating on physical and mental health

Binge eating can impact both our mind and body. Some of these effects are explained below, however, for more information see How Binge Eating affects our mental and physical health (Part 1).

Weight gain and obesity

People often binge eat foods that are high in calories, fat and sugar, which can exaggerate weight gain.[13]

Over 60% of people with a binge eating disorder are overweight

Insulin resistance and Type II diabetes

Binge eating can cause insulin resistance, meaning that the body can’t regulate blood sugar well. Over time, this can increase our chance of developing Type II Diabetes.[4,13,14]

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

Sleep problems

Extreme fullness before going to sleep can cause difficulties falling asleep or staying asleep (insomnia).

Individuals who have a higher body weight are also more likely to suffer from sleep apnea – a condition where we stop breathing while sleeping as fat builds up around the airways.[13,14]

RELATED — Sleep apnea: How to cure it and get your sleep back

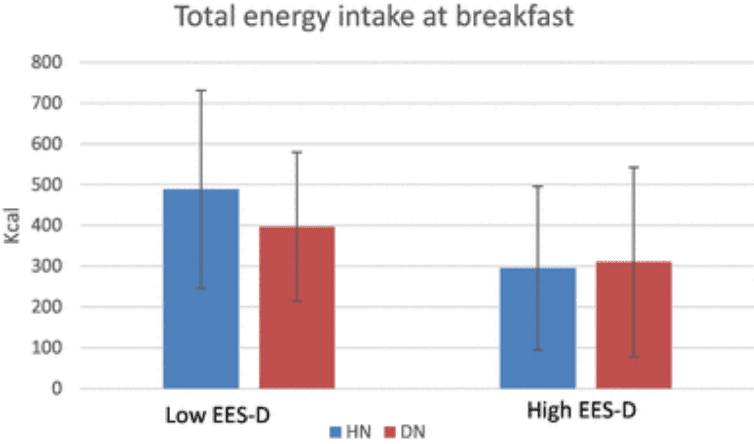

HN - habitual sleep, DN - partial sleep deprivation. Individuals reporting low depressive emotional eating ate less after DN than after HN at breakfast, but then they ate more throughout the day. Source: Rodgers, R., F., Partial sleep deprivation and food intake in participants reporting binge eating symptoms and emotional eating: preliminary results of a quasi-experimental study (Eating and Weight Disorders, 2018).

Malnutrition

The types of foods that people are more likely to binge eat are those that are energy dense and nutrient poor.

For any eating disorder, there is a higher risk of having several vitamin and mineral deficiencies, such as

- B vitamins

- Iron

- Calcium

- (RELATED — Calcium: For healthy bones, teeth and heart)

- Magnesium

- (RELATED — Magnesium: For a great night of sleep)

- Zinc

- (RELATED — Zinc: For immunity, skin health and libido)

- Omega 3’s and 6’s.[15]

Exhaustion and poor concentration

When the body tries to digest large amounts of food in one sitting, this takes a lot of energy which is why we feel sluggish and tired after overeating.

Binge eating disorder can cause feelings of fatigue, brain fog and poor concentration.

Anxiety

Being unable to control one’s eating habits can cause stress and anxiety for an individual.

This can also lead to social anxiety, especially in terms of embarrassment and shame when eating around others.[14]

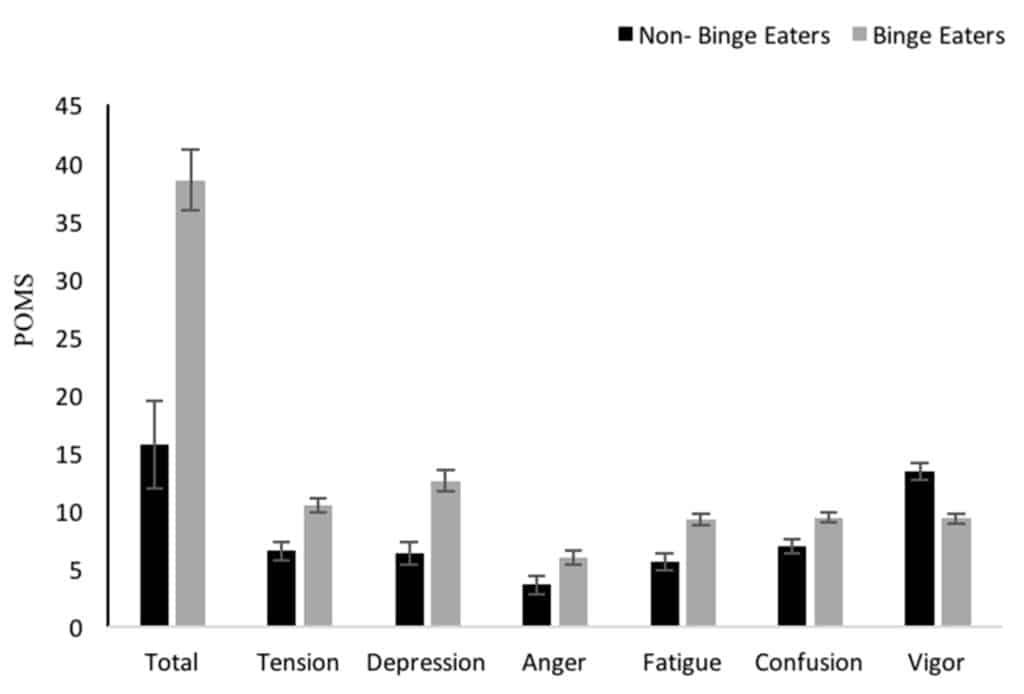

Source: Martyn, K., Mindfulness in Eating Is Inversely Related to Binge Eating and Mood Disturbances in University Students in Health-Related Disciplines (Nutrients 2020).

Social isolation and depression

As a result of binge eating behavior, people may isolate themselves in fear and shame of being around others when they are eating.

Depression can cause a cyclic trend of binge eating

Higher suicide risk

Having an eating disorder, such as binge eating, can be a risk factor for suicide attempts, especially if there is comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety and/or depression.[1]

RELATED — The Suicide Epidemic

Treatment for binge eating disorder

If your GP suspects that you might have an eating disorder, they are likely to refer you to an eating disorder specialist or a team.

A health professional team involved in eating disorder treatment often includes

- Doctors

- Psychologists

- Psychiatrists

- Dieticians[2]

Most people who have a binge eating disorder can be treated as an outpatient. However, if there are medical or psychiatric issues present, being admitted to hospital is also an option.

Binge eating disorder is the least researched of all eating disorders in terms of interventions

Current therapies that have shown to be useful are

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT)

- Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT)

- Group therapy

Social support from family, friends and health professionals is also important for eating disorder treatment.[16]

Family Based Therapy (FBT) has also shown to be favored among families in New Zealand.[1]

In New Zealand, the limitations of current treatment include

- Difficulty in primary health care to detect eating disorders

- Transition and referral to treatment due to long wait times

- Not enough professionals trained to treat eating disorders

Those who can’t get access to public treatment end up having to pay for private care, which in itself can present with financial difficulties.[1]

Overall, those who do get treatment early for a binge eating disorder often have a good prognosis of returning to healthy eating patterns.[2]

Tips to help control binge eating

Binge eating can be managed through several techniques including health behaviors, psychological treatment and social support.

More tips will be explored in future articles, but for now, here are the three most important tips to help control binge eating.

Keep a food diary and related emotions

Tracking your eating patterns and mood can be an effective way to identify emotional triggers for binge eating behavior. Studies that incorporate a self-help program have shown to reduce episodes of binge eating.[17,18]

Eat regular balanced meals and avoid dieting

Restricting yourself of food will prompt your body to seek the energy it needs in order to survive. Adhering to a regular eating pattern can help reduce the likelihood of binge eating.

Skipping meals can disrupt our blood sugar levels and also our mood.

Make sure you have enough energy in your diet (from protein, carbohydrates and fat). Also, having breakfast, can prevent you from binge eating at the end of the day.[17,18]

Stress relieving activities

Related Questions

1. Why do we binge eat?

There can be multiple reasons that drive binge eating behavior such as

- Yo-yo dieting

- Emotional dysregulation

- Means of coping with such emotions.[19]

2. What is the difference between binge eating disorder and overeating?

The difference between a binge eating disorder and overeating is the lack of control over our eating and associated thoughts, feelings and behaviors.

3. Are eating disorders a choice?

Much like other mental illnesses, eating disorders are stigmatized to believe that they are “all in people’s heads”.

However, no one chooses to have an eating disorder and it is a complex issue that deserves treatment, much like any other health issue.

4. How to get help for yourself or others who have a binge eating disorder?

If you are worried that yourself, or someone else, is dealing with binge eating, seeing a GP is a good first step to getting assessed and treated.

5. Is it possible to recover from an eating disorder?

Recovery from an eating disorder is higher if diagnosed early, however, the chances decrease the longer it goes untreated.

6. Does social media increase the prevalence of a binge eating disorder?

Social media has shown to increase body image issues and prevalence of a binge eating disorder.

However, eating disorders are a multifaceted issue and social media isn’t a sole predictor of eating disorders.

7. Do you have to be overweight to be diagnosed with a binge eating disorder?

A binge eating disorder can be diagnosed regardless of weight, but 66% of people are classified as obese.

This means that you can be of a healthy weight for your height and still have a binge eating disorder.[4,5]

If you liked the article, or have any questions, please let us know in the comment section below.

Having passion for mental health and nutrition, Carly’s goal is to become a registered psychologist with a focus on self-care – food, exercise, and sleep. She has a special interest in various mental health disorders, plant-based diets, and the relationship between food and mood.

Through evidence-based research, holistic approach to health and personal experience, Carly hopes to empower others’ well-being.

Carly is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect.

References

(1) Eating Disorders Association New Zealand. Submission to the New Zealand Government Mental Health Inquiry. [Internet]. (2018 Jun) [cited 2022 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.ed.org.nz/files/EDANZ_Submission_to_Mental_Health_Inquiry.pdf

(2) Meiklejohn, M. Eating Disorders [Internet]. Health Navigator. [Internet] (2022, Mar 22) [cited 2022, Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/health-a-z/e/eating-disorders/

(3) Muhlheim, L. When Did Eating Disorders First Appear? [Internet]. Verywell Mind. 2019 [cited 2022 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.verywellmind.com/history-of-eating-disorders-4768486

(4) National Eating Disorders Association. Health Consequences. [Internet] (2022) [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/health-consequences

(5) Cohen Marill, M. Binge Eating Disorder [Internet]. WebMD (2021 Oct 31) [cited 2022 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/binge-eating-disorder/binge-eating-disorder-medref

(6) Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA. Binge eating in children and adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;34(S1):S47-57. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/eat.10205

(7) Priory. Eating Disorder Statistics [Internet] (2022) [cited 2022 June 6]. Available from: https://www.priorygroup.com/eating-disorders/eating-disorder-statistics

(8) de Zwaan M. Binge eating disorder and obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2001 May;25(1):S51-5. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/0801699

(9) Strongman, S. Dying for help: eating disorder treatment waiting lists months long [Internet] (2021 Mar 22) [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/in-depth/438868/dying-for-help-eating-disorder-treatment-waiting-lists-months-long

(10) National Health Service UK. Overview: Binge Eating Disorder [Internet]. (2020 Dec 13) [cited 2022 Apr 11]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/binge-eating/overview/

(11) Mathes WF, Brownley KA, Mo X, Bulik CM. The biology of binge eating. Appetite. 2009 Jun 1;52(3):545-53. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666309000506?casa_token=F5Yj45nnuYoAAAAA:C9sd59lDGHjtCoNKwaFEHMR9vuty5_pNJ9203T3Fcp0YcU5sdsCZYAcHoRfKDoFZZPCx5VF1VQ

(12) Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological bulletin. 1991 Jul;110(1):86. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0033-2909.110.1.86

(13) Watson, S. Serious health problems caused by binge eating disorder. [Internet] (2021, Oct 20) [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/binge-eating-disorder/health-problems-binge-eating

(14) The Emily Program. Physical Effects of Binge Eating Disorder. [Internet] (2019, Jan 31) [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.emilyprogram.com/blog/physical-effects-of-binge-eating-disorder/

(15) Eckelkamp, S (2015). 5 super common nutrient deficiencies that are making you overeat [Internet] (2015, Oct 2) [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.prevention.com/food-nutrition/a20481018/nutrient-deficiency-and-overeating/

(16) Dingemans, A. E., Bruna, M. J., & Van Furth, E. F. (2002). Binge eating disorder: a review. International Journal of Obesity, 26(3), 299-307. DOI: https://www.nature.com/articles/0801949

(17) Link, R. 15 Helpful tips to overcome binge eating. [Internet] (2019, Nov 14) [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/how-to-overcome-binge-eating

(18) Axtell, B. The best things you can do to head off a binge. [Internet] (2021, Oct 20) [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/binge-eating-disorder/head-off-binge

(19) Watson, S. Why am I Binge Eating? [Internet] (2021, Mar 8) [cited 2022 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/binge-eating-disorder/why-binge-eating