Hannah King

BSc (Human Nutrition)

While the topic of fibre might be only of an interest to many when facing constipation, fibre has several other functions apart from supporting bowel movements.

Fibre can assist with:

- Metabolic health

- Gut microflora

- Cardiovascular health

- Gastrointestinal health

We should also ask ourselves what might be the health risks of not having fibre in our diets?

What is fibre?

Fibre can be defined as carbohydrate chains with ten or more sugar units attached to them that do not react with enzymes in the small intestine.

In more basic terminology, this means a type of carbohydrate that cannot be fully digested in our intestines. In fact, it is mostly unchanged when passing through the tract. We can find it in many plant-based foods like:

- vegetables

- fruit

- legumes

- grains[1]

Fibre has several functions, including supporting bowel movements, adding bulk to the stool, and preventing constipation.

Additionally, it plays a role in the prevention of many chronic diseases such as diabetes, bowel cancer, and cardiovascular disease.[2]

History of fibre

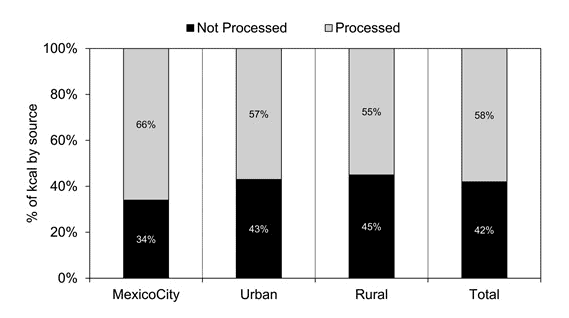

Early human diets were rich in minimally processed foods, consisting of a variety of wild plants and animal proteins. However, following the Industrial Revolution, changes in dietary habits gave way to a significant nutritional shift as food processing became widespread.[3] Though this became most evident post World War II, when convenient and more shelf-stable foods were introduced.[4]

In fact, according to Cordain et al. 2005 food staples and processing methods introduced have been shown to alter seven key nutritional characteristics of ancestral diets, such as:

- glycemic load

- fatty acid composition

- macronutrient profile

- micronutrient density

- acid–base balance

- sodium–potassium ratio

- fibre content[3]

This transition also brought about a rise in the intake of:

- added sugars

- sodium

- saturated fats

all of which contribute to the greater incidence of non-communicable diseases we see today.

RELATED — Health Risks: Trans and Saturated Fats

The current understanding of dietary fibre and its protective role in health was revived in the 1970s by pioneers Dennis Burkitt and Hugh Trowell.

Their recognition of the link between low fibre intake and chronic diseases sparked renewed interest in fibre research. Between 1966 and 1972, Burkitt drew on his observations from Africa and insights from other researchers to propose the idea that a low-fibre diet increased the risk of:

- coronary heart disease

- diabetes

- obesity

- dental caries

- vascular disorders

and large bowel diseases such as:

- diverticulosis

- appendicitis

- colorectal cancer

Then, Burkitt’s hypothesis demonstrated fibre as a protective factor in modern disease prevention.[5]

Different types of fibre

It can get confusing to differentiate between the various types of fibres, with the vast range of recommendations out there that link the various types to particular benefits.

Often, the terms “soluble” and “insoluble” fibre are used where soluble fiber is the type that dissolves in water, forming a gel-like substance, whereas insoluble fiber doesn’t dissolve in water and adds bulk to stool.[6]

Soluble fiber dissolves in water, forming a gel-like substance

However, they aren’t necessarily fully accurate because fibre’s solubility can vary based on its source and processing. Another way we may classify fibres is by:

- fermentability (how easily they are broken down by gut bacteria)

- viscosity (how much they thicken when mixed with fluids)

For example, cellulose (from green plants like algae) is insoluble, non-viscous, and poorly fermented, while pectins (from fruits and vegetables) are highly soluble, viscous, and highly fermentable.[2]

What’s important to understand here is that the different properties of fibres, such as solubility, viscosity, and fermentability, affect our digestive health and overall well-being in their own distinct ways.

Consuming a variety of fibers in your diet allows you to gain the full range of these beneficial effects.

Why is fibre important?

Fibre plays several important roles in supporting processes in the body:

- Metabolic health – Improved insulin sensitivity, glycaemic status, and lipid profile, as well as body weight and abdominal fat management.

- Gut microflora – Improved microbial health and variety, enhanced production of metabolites from gut microflora (like short-chain fatty acids), which are beneficial for health.

- Cardiovascular health – Reducing chronic inflammation and cardiovascular risk.

- Gastrointestinal health – Health and integrity of the colon, colonic motility, and reducing the risk of cancer in the gut.[7]

More recently, evidence suggests that these benefits are partly driven by fiber’s positive influence on the gut microbiome, an area of growing scientific interest.

In contrast, low fibre intake is associated with various health risks, which is why global dietary guidelines consistently promote adequate fibre consumption.

Fibre intake and disease prevention

The benefits that fibre provides, like those listed above, are an integral part of disease prevention. A wide range of evidence supports this.

Heart Disease

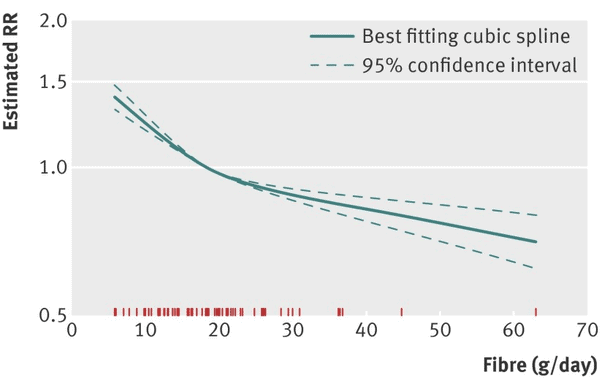

A systematic review and meta-analysis looking at the association between fibre intake, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease found that increased dietary fibre intake is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease.

More specifically, for every 7g of fibre, there was a 9% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Findings from this study support biological mechanisms linking fibre to cardiovascular health.

One of these mechanisms involves soluble fibre, which forms a gel-like substance in the gut and slows the absorption of sugar and fat after meals, helping regulate blood glucose and lipid levels.

Additionally, in the large intestine, soluble fibre and resistant starch are fermented by gut bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids, which may lower cholesterol.

Improved cholesterol, along with hypertension, central obesity, and insulin sensitivity, are all key factors for reducing cardiovascular disease risk and can result from increased fibre intake.[8]

Hypertension

Hypertension, which is linked to the risk of heart disease, can also be prevented through integrating fibre into the diet.

A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials found that higher dietary fibre intake was linked to modest reductions in blood pressure among healthy individuals, with the greatest effects seen in beta-glucan-rich fibres found in oats and barley.

Systolic blood pressure on average lowered by 2.9mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 1.5mmHg for an increase in beta-glucans by just 4g/day.[9]

Type 2 Diabetes

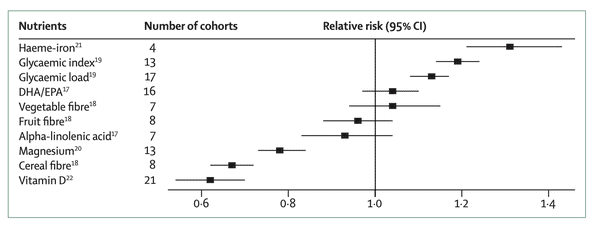

A meta-analysis investigating diet and type 2 diabetes incidence found strong evidence that wholegrains and cereal fibre are protective against the disease.

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

The health benefits of whole grains and cereal fibre that contribute to this protective relationship may be due to higher levels of phytochemicals, vitamins, and minerals they have compared to refined grains that lose this during processing.

High intake appears to improve insulin sensitivity, lower fasting insulin levels, reduce levels of inflammation, and increase levels of adiponectin, a hormone that helps regulate blood sugar. All of which can reduce risk of type 2 diabetes.[10]

The Lancet has also highlighted the preventive benefits of fibre, presenting evidence from long-term studies showing how diet influences blood sugar control.[11]

Colorectal Cancer

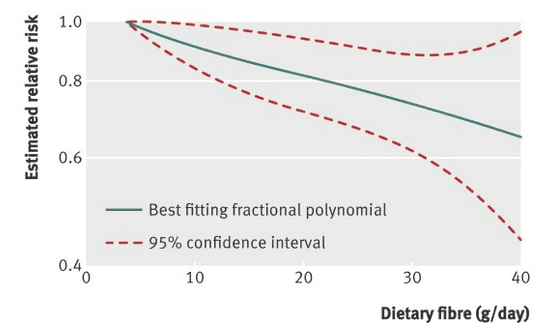

A systematic review and meta-analysis looking at dietary fibre, wholegrains and risk of colorectal cancer also found similar findings to those mentioned above.

They noted that a 10g increase in daily intake of total dietary fibre or cereal fibre was associated with a 10% reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer.

Similarly, the study found that wholegrains were also impactful for reducing the risk of colorectal cancer. This is also an important finding as wholegrains tend to serve as a great source of fibre.[12]

Increase of 10% daily intake of dietary fibre is associated with a 10% reduction in the risk of colorectal cancer

Mechanisms by which fibre could play a role in colorectal cancer risk include increased bulk of stools, dilution of carcinogens in the colon, reduced transit time or amount of time food sits in the gut, and bacterial fermentation of fibre to short-chain fatty acids.[13]

Weight Management

Higher dietary fibre intake is also linked to body weight management, specifically reduction in body weight, which has been shown in randomised controlled trials and prospective cohort studies.

From a biological point of view, fibre enhances satiety through increased chewing and increases the bulk of food. This slows digestion, improving blood glucose and insulin responses, and moderating fat and carbohydrate metabolism.

Additionally, in the large intestine, fibre is fermented and produces short-chain fatty acids, which are important for metabolic health.[14]

One prospective cohort study in Europe found that a 10g/day increase in total dietary fibre intake was associated with a 39g reduction in weight per year and 0.08 cm reduction in waist circumference.

Cereal fibre had the strongest effect, with a 77g reduction in weight per year and a 0.10cm reduction in waist circumference, further highlighting cereal fibre’s beneficial role in chronic disease prevention/management.[15]

Who is at risk of poor fibre intake?

Many New Zealanders are at risk of inadequate fibre mainly due to reasons such as the preference of white or light-grain breads, over whole-grain breads, and only 1 in 11 adults meeting the recommended vegetable intake guidelines.

Unfortunately, among low socioeconomic Māori and Pacific communities, consumption of refined foods is even higher, adding to the disproportionate burden of disease in these groups.[16,17]

Globally, men and older adults are most affected by poor fibre intake and health outcomes. Men due to lower intake and poorer diets, and older adults due to the delayed health effects of long-term low fibre consumption.

Men and older adults usually have poor fibre intake and health outcomes

Populations in low and middle-income socio-demographic regions are also more at risk because of poor access to fibre-rich foods, low awareness, and high food costs.

The burden is most evident in Southern and Central sub-Saharan Africa. Even in countries like the USA, UK, and Japan, low-income groups are at risk due to the increased availability of ultra-processed foods and limited nutrition education.[18]

Particular individuals are at higher risk of low fibre intake due to intentional dietary changes. Low-fibre diets are prescribed in cases such as acute IBD flares, bowel obstructions, or before procedures such as colonoscopies, and while usually temporary, repeated use can lead to chronically low intake.

Restrictive diets like keto or the carnivore diet, often low in fibre, may also increase this risk if followed without professional guidance.

Consulting a healthcare professional, such as a dietitian, is strongly recommended.[19,20]

Related Questions

1. What are foods high in dietary fibre?

Some familiar foods that are rich in dietary fibre and worth implementing into your diet include:

- Psyllium husk

- Wheat bran

- Seeds (especially chiaseeds and linseeds)

- Some breakfast cereals (like All Bran)

- Legumes (especially red kidney beans and chickpeas)[21]

2. Can the consumption of fibre assist with constipation?

Yes, fibre helps to support regular bowel movements and therefore prevent constipation.

For best effects, adequate fluid intake should be maintained.

3. How can I work towards getting 25g of fibre in a day?

Aim to consume the following foods daily:

- 5 servings of vegetables and 2 servings of fruit a day

- Choose wholemeal or wholegrain bread, pasta, and rice

- Choose breakfast cereals high in fibre such as Weetabix, oats, or All-bran

References

(1) Kendall, C. W. C., Esfahani, A., & Jenkins, D. J. A. (2010). The link between dietary fibre and human health. Food Hydrocolloids, 24(1), 42-48.

(2) British Nutrition Foundation. (2023). Fibre – For Professionals https://www.nutrition.org.uk/nutritional-information/fibre/

(3) Cordain, L., Eaton, S. B., Sebastian, A., Mann, N., Lindeberg, S., Watkins, B. A., O’Keefe, J. H., & Brand-Miller, J. (2005). Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century, 2. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 81(2), 341-354.

(4) Popkin, B. M. (2017). Relationship between shifts in food system dynamics and acceleration of the global nutrition transition. Nutrition Reviews, 75(2), 73-82. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuw064

(5) Cummings, J. H., & Engineer, A. (2018). Denis Burkitt and the origins of the dietary fibre hypothesis. Nutr Res Rev, 31(1), 1-15.

(6) Akbar, A., & Shreenath, A. P. (2023). High Fiber Diet.

(7) Barber, T. M., Kabisch, S., Pfeiffer, A. F. H., & Weickert, M. O. (2020). The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre. Nutrients, 12(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103209

(8) Threapleton, D. E., Greenwood, D. C., Evans, C. E., Cleghorn, C. L., Nykjaer, C., Woodhead, C., Cade, J. E., Gale, C. P., & Burley, V. J. (2013). Dietary fibre intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj, 347, f6879. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6879

(9) Evans, C. E., Greenwood, D. C., Threapleton, D. E., Cleghorn, C. L., Nykjaer, C., Woodhead, C. E., Gale, C. P., & Burley, V. J. (2015). Effects of dietary fibre type on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of healthy individuals. J Hypertens, 33(5), 897-911.

(10) Neuenschwander, M., Ballon, A., Weber, K. S., Norat, T., Aune, D., Schwingshackl, L., & Schlesinger, S. (2019). Role of diet in type 2 diabetes incidence: umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective observational studies. Bmj, 366, l2368. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l2368

(11) Ley, S. H., Hamdy, O., Mohan, V., & Hu, F. B. (2014). Prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: dietary components and nutritional strategies. The Lancet, 383(9933), 1999-2007.

(12) Aune, D., Chan, D. S., Lau, R., Vieira, R., Greenwood, D. C., Kampman, E., & Norat, T. (2011). Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Bmj, 343, d6617. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d6617

(13) Lipkin, M., Reddy, B., Newmark, H., & Lamprecht, S. A. (1999). Dietary factors in human colorectal cancer. Annual review of nutrition, 19(1), 545-586.

(14) Reynolds, A., Mann, J., Cummings, J., Winter, N., Mete, E., & Te Morenga, L. (2019). Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The Lancet, 393(10170), 434-445. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

(15) Du, H., Boshuizen, H. C., Forouhi, N. G., Wareham, N. J., Halkjær, J., Tjønneland, A., Overvad, K., Jakobsen, M. U., Boeing, H., & Buijsse, B. (2010). Dietary fiber and subsequent changes in body weight and waist circumference in European men and women. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 91(2), 329-336.

(16) Ministry of Health. (2024). Annual Update of Key Results 2023/24: New Zealand Health Survey. https://www.health.govt.nz/publications/annual-update-of-key-results-202324-new-zealand-health-survey

(17) Ministry of Health. 2020. Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults: Updated 2020. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

(18) M., Song, X. H., Wang, L. F., Li, Y., Zhang, X. J., Zhu, L., Cai, J., Ye, J. M., Zhou, G., & Zeng, Y. (2023). The global disease burden attributable to a diet low in fibre in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019. Public Health Nutr, 26(4), 854-865. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980022001987

(19) Wajeed Masood, Pavan Annamaraju, Mahammed Z. Khan Suheb, & Kalyan R. Uppaluri. (2023). Ketogenic Diet. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499830/

(20) Amy Richter. (2024). What to eat and avoid on a low-fiber diet.

(21) Food Standards Australia New Zealand. (N/A). Australian Food Composition Database – Release 2.0 (https://afcd.foodstandards.gov.au/foodsbynutrientsearch.aspx?nutrientID=AOACDFTOTW