Angela Mastronardi

(B.Med., CYT)

The way we breathe changes according to what we are doing and how we are feeling. Our breathing can adjust instantaneously to match our present needs.

The different types of breathing we will look into are:

- Nasal and mouth breathing

- Diaphragmatic breathing

- Costal breathing

- Clavicular breathing

Our breathing can also change based on pace, rhythm, length, depth, lungs engagement (which part of our lungs is working more) and if we breathe in through our nose or mouth.

Nasal & mouth breathing

The mouth is principally related to the digestive system, and it has a place in the respiratory system only as an emergency passage for inhaling air. This means that using it to breathe should be avoided at all cost if nose breathing is possible.

Our nose is specifically designed for breathing

The reasons why nose breathing should be our preferential way to breathe is because our nose:

- filters

- humidifies

- warms up

the air so it reaches our lungs in most available and purest form.

Mouth breathing delivers cold unfiltered air to our lungs, which will have undesirable particles, increasing the risk of lung infections.

Moreover, mouth breathing greatly dehydrates the body.

Consistent mouth breathing will likely lead to the development of:

- Long and narrow faces

- Narrow mouths and high palatal vaults

- Dental malocclusion

- Gummy smiles

On a social and behavioural level, the reduced presence of oxygen and the inappropriate sleep due to mouth breathing can lead to misdiagnosis of attention deficit disorder (ADD) and hyperactivity in many children.[1]

Mouth breathing naturally engages the upper part of the chest, generating breathing rhythms that are shallow and fast. These breathing patterns are linked to an over-activation of the sympathetic nervous system, the branch that responds to arousal, stress and anxiety.

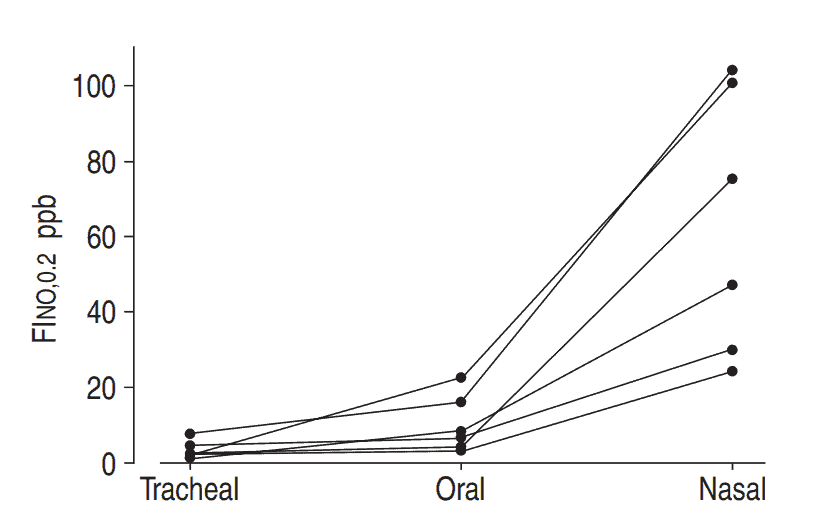

Using nasal breathing increases the levels of nitric oxide (NO), which is mainly produced in the nasal cavity. Nitric Oxide is a pluripotent gas with potent vasodilating and antimicrobial activity.[2] When we breathe through the mouth, we only intake a very small quantity of nitric oxide.

Source: Marteus, H. Nasal and oral contribution to inhaled and exhaled nitric oxide: a study in tracheotomized patients. (2002)

Finally, the brain areas that activate with nasal breathing are different from the ones with mouth breathing.

Nasal breathing engages brain circuits that allow better emotional recognition and memory recall, ultimately improving cognitive performance.[3]

Diaphragmatic breathing

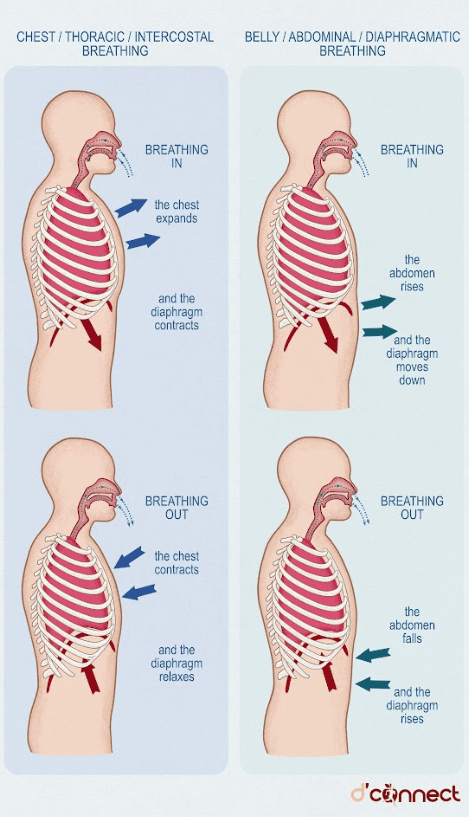

Also called abdominal breathing, this is a type of breath that engages the diaphragmatic muscle.

The diaphragmatic muscle, which is shaped as a dome, is located at the bottom of our ribs, and it contracts as it flattens during inhalation. When we breathe out, the diaphragm relaxes and assumes its dome shape, while the belly contracts gently inward.

Newborn and young children use belly breathing, before learning to breathe also with the upper torso.[4]

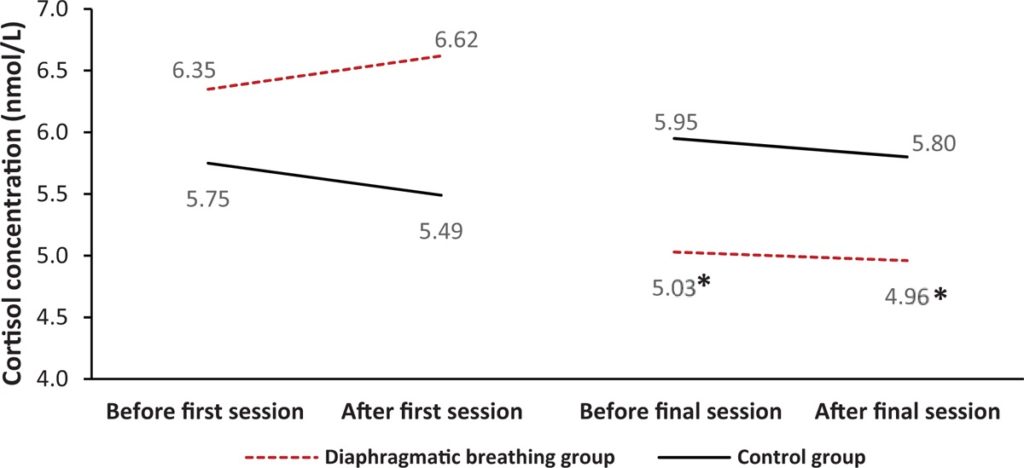

Diaphragmatic breath has been in the eye of the scientific community for a long time now due to its healing capacities. Evidence suggests that diaphragmatic breathing may decrease stress as measured by physiologic biomarkers, as well as psychological self-report tools.[5]

Source: Hopper, Susan I. Effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing for reducing physiological and psychological stress in adults: a quantitative systematic review. (2019)

When we feel stressed, with high levels of anxiety present, this promotes the use of the chest muscles, to the point that in many cases the diaphragm becomes rigid. However, it is easily achievable to retrain the diaphragm through breathwork practice.

An elastic diaphragm and the ability to breath in the tummy and ribs foster the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, allowing the body to be in a space of nurture that supports the balance and health of the whole body-mind system.

Losing the connection to abdominal breathing has the dramatic consequences of keeping us in fight-or-flight mode overtime, which causes physical and psychological issues.

This is where establishing a consistent breathwork practice can bring back a balanced activation of the autonomic nervous system.

Costal breathing

Costal breathing, also known as thoracic breathing, uses the intercostal muscles of the ribs as primary drive of inhalation and exhalation.

Usually, when breathing with the diaphragm, the lower ribs are also engaged in the breath.

Research points out that subconscious fast costal breathing is a sign of stress and it is unhealthy. We naturally call upon this way of breathing when in fight-or-flight response, and therefore in an autonomic sympathetic activation.

Conscious and voluntary fast costal breathing increases temperature, as well as mental acuity and focus.

When done with awareness, conscious costal breathing can increase the activation of the sympathetic activity without falling into the negative cascade of the stress response.

Clavicular breathing

Clavicular breathing engages the muscles of the upper part of the chest and back, shoulders and neck. The collarbone lifts as the upper part of the lungs expands with the inhalation.

Clavicular breathing is used only under extreme physical exertion and when obstructive airway diseases, such as asthma, are experienced.

Clavicular breathing can be practiced during a breathwork practice when we are aiming to engage the full lung capacity, as well.

Clavicular breathing is seen as dysfunctional

This is because it reduces an adequate intake of oxygen for the body and stimulates an overactive sympathetic nervous system, which leads to increased stress levels.

RELATED — Understanding Stress: The Silent Killer

Normal breathing can be thoraco-abdominal, with the chest mostly used, or abdominal-thoracic, when the abdomen is more used.

Recent studies have observed that men tend to breathe more in an abdominal-thoracic manner, while women prefer thoracho-abdominal breathing.

Related Questions

1. Do breathing nose strips help you breathe better?

Nasal strips are flexible bands that fit along the bridge of the nose. They help to open the nasal passages, improving airflow and therefore make breathing easier.

They also may reduce snoring.

2. Does deep breathing make anxiety worse?

If by “deep breathing” we mean taking deep, fast chest breaths, then yes, it does worsens anxiety.

However, if we take deep, slow abdominal breaths, this counteracts anxiety by activating the calming parasympathetic response.

3. What is a rhinomanometer?

A rhinomanometer is a tool that measures airflow and resistance in the nostrils during breathing.

Objectively measuring the nasal pressure, this test detects possible obstructions in the airways, like inflammation present in the nasal cavity, nasal polyps, hypertrophy in the turbinates, or a deviated septum.

If you have any questions about the article, or different types of breathing, please let us know in the comments. Also, if you would like to read a more in-depth article on breathing, we suggest Introduction to Breathing: Our foundation of health.

Bernadeth’s passion in cooking, food and health led her to learn more about nutrition and the importance of functional foods. Throughout the years, she gained special interest in sports and performance nutrition, and the varieties of diets around the world. As a nutritionist, Bernadeth’s goal is to encourage a healthy-balanced diet and share the evidence-based nutrition knowledge in order for people to live healthier and longer lives.

Bernadeth is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect

References

(1) Jefferson Y. Mouth breathing: adverse effects on facial growth, health, academics, and behavior. Gen Dent. 2010 Jan-Feb;58(1):18-25; quiz 26-7, 79-80. PMID: 20129889

(2) Lundberg JO. Nitric oxide and the paranasal sinuses. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2008 Nov; 291(11): 1479-84. doi: 10.1002/ar.20782. PMID: 18951492.

(3) Zelano C, Jiang H, Zhou G, Arora N, Schuele S, Rosenow J, Gottfried JA. Nasal Respiration Entrains Human Limbic Oscillations and Modulates Cognitive Function. (2016)

(4) Nature.Dassios, T., Vervenioti, A. & Dimitriou, G. Respiratory muscle function in the newborn: a narrative review. Pediatr Res 91, 795–803 (2022). Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41390-021-01529-z#citeas

(5) Hopper SI, Murray SL, Ferrara LR, Singleton JK. Effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing for reducing physiological and psychological stress in adults: a quantitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2019 Sep; 17(9): 1855-1876. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003848. PMID: 31436595.

So informative and easy to understand. Thank you.