Megan Rodden

(BCS, DipNat, MedHerb, NMHNZ)

The gut is a complex system that our body relies on to maintain health. In traditional naturopathic philosophy the gut is referred to as “the seat of health”.

This concept dates back to traditional healing systems like Hippocratic medicine and Ayurvedic medicine, which both recognised the pivotal role of the gut in overall health.[1]

RELATED — Introduction to Ayurveda: Ancient medicinal healing methods

Today science is catching up, with research confirming that a balanced gut microbiome can support everything from mental clarity to reduced inflammation.

Understanding gut health

When we refer to gut health as a whole we are talking about the entire digestive tract or gastrointestinal system. This system begins in the mouth, where food enters and includes the

- oesophagus

- stomach

- intestines

- colon

The liver, gallbladder and pancreas are the accessory organs of this system.

Gastrointestinal system begins in our mouth

The main function of the whole system is to break down food into fuel for the body but gut health also plays a bigger role in our overall health.

Dysfunction in the gut can lead to problems such as

- intestinal permeability

- nutrient malabsorption and deficiencies

- food intolerances

which can widely impact other body systems.

What is the microbiome?

Our gut also houses a very important community of microbes known as the gastrointestinal microbiome. This is like an inner garden made up of different microorganisms and plays a role in

- digestion

- immune and skin health

- mood and energy

and many different areas of our overall health. When our microbiome is healthy and balanced our whole body works better.

Research over the last 15-20 years has begun to show the vast interactions between the gut microbiome and human health. Studies have linked the microbiome to a number of chronic diseases including

- cardiovascular disease

- obesity

- diabetes

- depression

- inflammatory bowel disease[2]

Research also indicates that genetics only have a minor influence on our microbiome whilst our environment and diet can significantly alter the microbiome and its impact on our health.[3]

Why is gut health so important

The gut plays a central role in nearly every aspect of wellbeing – from digestion and nutrient absorption to immune function and mood regulation.

Digestion and nutrient absorption

The health of the gut directly affects our ability to fuel our body with nutrients. We need a healthy gut lining and balanced microbiome to break down food efficiently and absorb nutrients like essential vitamins and minerals.

When the gut is compromised with a poor diet, inflammation, stress or bacteria imbalances, it can be difficult to absorb nutrients even when we are eating enough.[4]

When gut health is compromised it can be difficult to absorb nutrients

For example, one study demonstrated that good gut bacteria are needed for extracting energy and nutrients. Researchers studied 27 adults with obesity or impaired glucose tolerance and measured their nutrient and energy absorption through stool calorie loss.

Microbiome changes were also measured after participants were given a diet phase with reduced calories and an antibiotic phase or placebo.

The antibiotic treatment resulted in significant drops in microbiome diversity and increased stool calorie and nutrient loss compared to placebo. Both diet and antibiotic treatment resulted in higher levels of the bacteria named Akkermansia muciniphila.[5]

Immune system

A whopping 70-80% of the body’s immune cells live in the gut and studies show gut bacteria, mucous and lining all impact our immunity.[6]

For example, studies have identified gut microbes can help regulate immune response and prevent autoimmunity. Gut microbes interact with T cells, educating and modulating their responses, which calm inflammation and control cells that fight infection.[7]

In 2013, animal studies discovered that gut microbes produced short-chain fatty acids (SFCA), which help regulatory T cells with growth and activity affecting the immune system.[8]

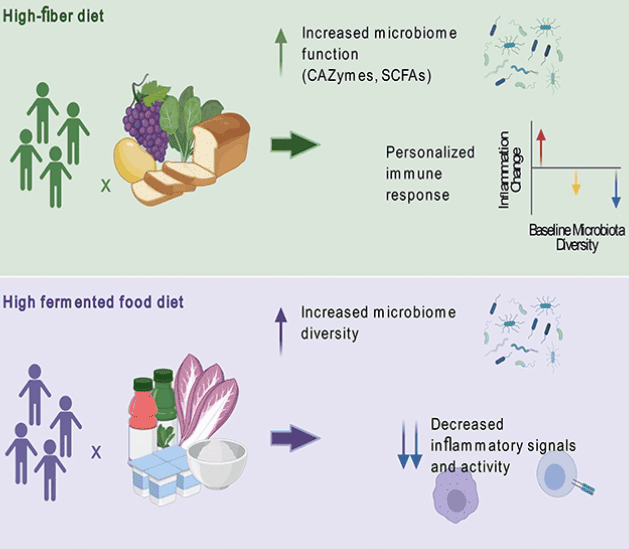

Recent research in humans has shown this link between the microbiome and immune system function. One study found that dietary interventions such as high fibre and high fermented foods altered gut flora and improved immune system function.

The 17 week randomised trial assigned healthy adults two diets of either high fibre or high fermented foods (yogurt, kimchi, kombucha) and measured changes in both the gut microbiome and immune system, such as immune-cell profiles and inflammation markers.

The high fibre group responded differently based on their pre-study microbiome with some individual improvements. The fermented food group increased their microbial diversity and steadily lowered their levels of inflammation markers and immune profile.[9]

Mental health

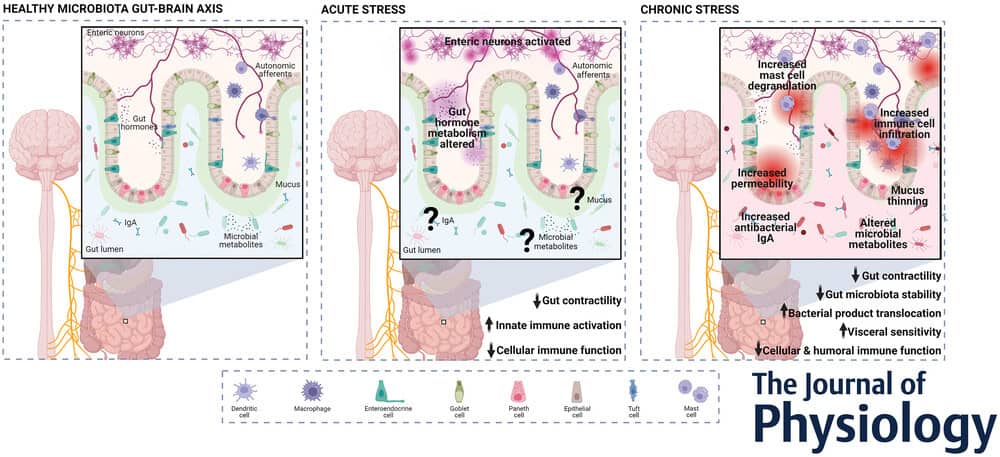

There is an important connection between mental health and our gut; this link is known as the gut brain axis. This involves millions of nerves that send signals to the brain as well as gut bacteria that produce chemicals to help make neurotransmitters, which help with mood balance, like serotonin.[10]

RELATED — Neurotransmitters: Serotonin 5-HT (for mood, sleep and digestion)

Studies have also shown that imbalances in the microbiome are linked to mental health disorders.[11]

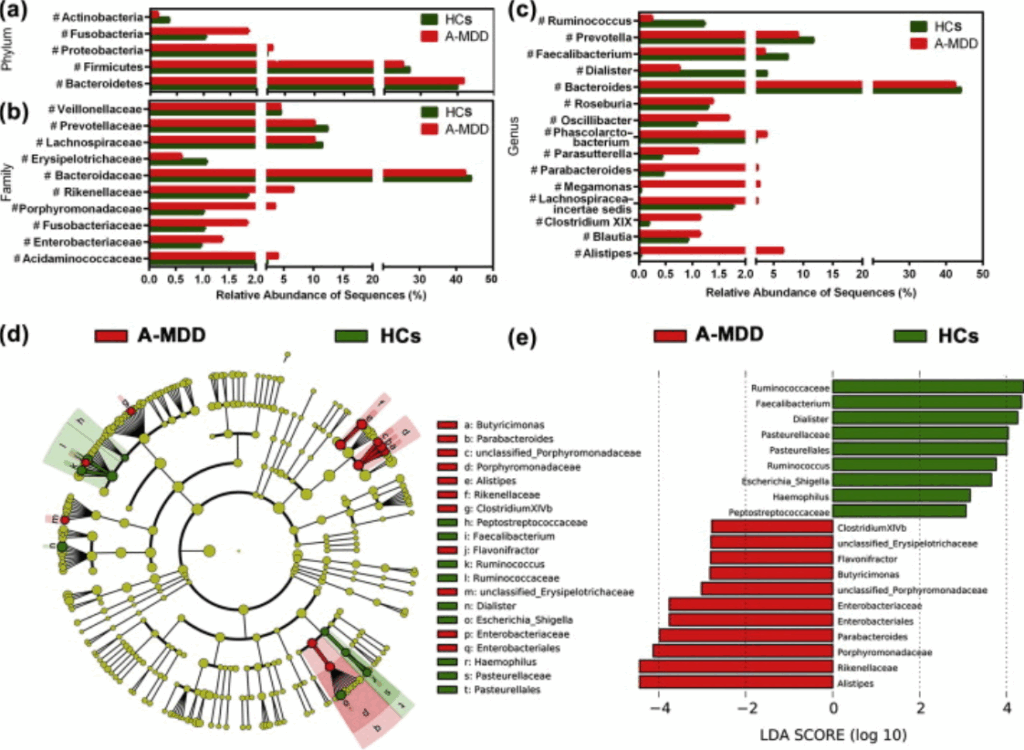

One study found that patients with depression had differences in the composition of their gut microbes. The study looked at fecal samples of people with depression compared to healthy controls. Fecal samples were analysed from 46 patients with major depressive disorder and 30 healthy controls.

Comparison of relative abundance at the bacterial phylum (a), family (b) and genus (c) levels between HC and A-MDD groups.

Results showed two bacteria in excess in patients with depression – Enterobacteriaceae and Alistipes and one bacteria in significantly higher abundance in healthy controls – Faecalibacterium. People with more severe depression also tended to have lower levels of Faecalibacterium.[12]

Signs and symptoms of poor gut health

Poor gut health may show up in a number of different ways. Common digestive symptoms include:

- bloating and excess or foul smelling gas

- constipation or diarrhea

- reflux and heartburn

- abdominal discomfort

The effects of an imbalanced gut may also go much further.

Other possible symptoms include: skin issues like acne or eczema as well as bodywide symptoms like fatigue, frequent infections, or multiple food sensitivities.[12]

How to improve our gut health

There are a number of things we can do to improve our gut health with our diet, lifestyle and environment being very impactful.

Diet

What to include

We need to feed our microbiome. It likes wholefoods, fibre and variety. To encourage a healthy diversity of gut bacteria we need to include lots of plant variety and 30 different types per week is the recommended goal, based on research.

The largest study on the human microbiome, The American Gut Project, found that people who ate more than 30 different plant foods per week had the most diverse and healthy gut microbiomes.[13,14]

What to Avoid

In order to keep our gut happy and healthy we also need to avoid things that create inflammation in the gut and feed harmful bacteria. Inflammatory foods include highly processed sugary foods, pesticides, chemical additives and preservatives.[15]

Optimise Digestion

Digestion begins in the mouth so simple habits like chewing food properly and timing our hydration can help optimise digestion. Chewing well helps break down food and signals our digestive system to release the right enzymes to easily absorb nutrients.

Drinking water between meals, rather than during supports natural stomach acid levels and prevents dilution of those important enzymes.

Avoid processed foods

Probiotics and fermented foods

Research indicates that supplementing with probiotics and fermented foods can help support a healthy gut microbiome.[16]

Fermented foods are prepared with salt and sometimes vinegar and left to ferment and contain beneficial bacteria. This is a way of preserving foods to extend their usability that has been around for centuries and societies all over the world included them in their diet.

Research now shows there are a number of benefits to including fermented foods in our daily diet, such as supporting gut, brain and immune health.[17]

Small consistent changes in these areas can lead to noticeable improvements in digestion and overall wellbeing.

Lifestyle

Daily habits can have a powerful impact on our gut health, including exercise, sleep and stress management.

Regular Exercise

Movement helps stimulate digestion and research shows regular exercise can positively modify the gut microbiome, increasing beneficial microbes.[18]

Quality Sleep

Quality sleep is needed for overall health and wellbeing as deep sleep is needed for important functions like tissue repair and inflammation regulation. Sleep quality and gut health are closely linked with studies suggesting that people with sleep disorders are at an increased risk of also having gastrointestinal disorders.[19]

RELATED — Great Sleep means Great Health: 17 Health Benefits of Good Sleep

Stress Management

Managing stress is important as high stress levels can disrupt the gut-brain connection, promote gut bacteria imbalances and contribute to symptoms like bloating or discomfort. Stress hormones also impact digestion and chronic stress can cause altered secretion of digestive juices.[20]

Stress management strategies, such as mindfulness meditation have been found to have a positive impact on chronic gut conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Megan helps her clients to rebalance their bodies through holistic nutrition, herbal medicine and a naturopathic lifestyle. Her personal health journey transitioned her from a communications consultant to a naturopath, sparked by struggles with chronic health issues, particularly after having children and finding vital support from natural therapies…

If you would like to learn more about Megan, see Expert: Megan Rodden.

References

(1) Chouhan, Poona & Rajpurohit, Hemant. (2024). Exploring The Ayurvedic Perspective of Gut Health and Its Correlation with Mental Well-Being. African Journal of Biomedical Research. 6601-6607. 10.53555/AJBR.v27i3S.5626. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387854520_Exploring_The_Ayurvedic_Perspective_of_Gut_Health_and_Its_Correlation_with_Mental_Well-Being

(2) Hills RD Jr, Pontefract BA, Mishcon HR, Black CA, Sutton SC, Theberge CR. (2019). Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients. doi: 10.3390/nu11071613. PMID: 31315227; PMCID: PMC6682904.

(3) Rothschild, D., Weissbrod, O., Barkan, E. et al. (2018). Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 555, 210–215

(4) Zuvarox T, Belletieri C.(2023) Malabsorption Syndromes. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553106/

(5) Basolo A, Hohenadel M, Ang QY, Piaggi P, Heinitz S, Walter M, Walter P, Parrington S, Trinidad DD, von Schwartzenberg RJ, Turnbaugh PJ, Krakoff J. (2020). Effects of underfeeding and oral vancomycin on gut microbiome and nutrient absorption in humans. Nat Med. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0801-z. Epub 2020 Mar 23. PMID: 32235930.

(6) Wiertsema SP, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Garssen J, Knippels LMJ. (2021).The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients. doi: 10.3390/nu13030886. PMID: 33803407; PMCID: PMC8001875.

(7) Sharma A, Sharma G, Im SH. Gut microbiota in regulatory T cell generation and function: mechanisms and health implications. (2025). Gut Microbes. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2025.2516702. Epub 2025 Jun 15. PMID: 40517372; PMCID: PMC12169050.

(8) Arpaia, N., Campbell, C., Fan, X. et al.(2013). Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 504

(9) Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D, Dahan D, Merrill BD, Yu FB, Topf M, Gonzalez CG, Van Treuren W, Han S, Robinson JL, Elias JE, Sonnenburg ED, Gardner CD, Sonnenburg JL. (2021). Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.019.

(10) Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol. PMID: 25830558; PMCID: PMC4367209. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4367209/

(11) Rogers GB, Keating DJ, Young RL, Wong ML, Licinio J, Wesselingh S. (2016). From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: mechanisms and pathways. Mol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.50.

(12) Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Mao H, Ma Z, Yin Y, Wang W, Tang W, Tan Z, Shi J, Li L, Ruan B. (2015). Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun.doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016.

(13) Zhang YJ, Li S, Gan RY, Zhou T, Xu DP, Li HB. 920150. Impacts of gut bacteria on human health and diseases. Int J Mol Sci. doi: 10.3390/ijms16047493. PMID: 25849657; PMCID: PMC4425030.

(14) McDonald D, Hyde E, Debelius JW, Morton JT, Gonzalez A, Ackermann G, Aksenov AA, Behsaz B, Brennan C, Chen Y, DeRight Goldasich L, Dorrestein PC, Dunn RR, Fahimipour AK, Gaffney J, Gilbert JA, Gogul G, Green JL, Hugenholtz P, Humphrey G, Huttenhower C, Jackson MA, Janssen S, Jeste DV, Jiang L, Kelley ST, Knights D, Kosciolek T, Ladau J, Leach J, Marotz C, Meleshko D, Melnik AV, Metcalf JL, Mohimani H, Montassier E, Navas-Molina J, Nguyen TT, Peddada S, Pevzner P, Pollard KS, Rahnavard G, Robbins-Pianka A, Sangwan N, Shorenstein J, Smarr L, Song SJ, Spector T, Swafford AD, Thackray VG, Thompson LR, Tripathi A, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Vrbanac A, Wischmeyer P, Wolfe E, Zhu Q; American Gut Consortium; Knight R. (2018). American Gut: an Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research. mSystems. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00031-18. PMID: 29795809; PMCID: PMC5954204. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5954204/

(15) Ma, X., Nan, F., Liang, H., Shu, P., Fan, X., Song, X., … & Zhang, D. (2022). Excessive intake of sugar: An accomplice of inflammation. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 988481.https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.988481

(16) Leigh, S.-J., Uhlig, F., Wilmes, L., Sanchez-Diaz, P., Gheorghe, C.E., Goodson, M.S., Kelley-Loughnane, N., Hyland, N.P., Cryan, J.F. and Clarke, G. (2023). The impact of acute and chronic stress on gastrointestinal physiology and function: a microbiota–gut–brain axis perspective. J Physiol.

(17) Qian, Xiaoqi, and Jianjian Zhang. (2024). Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Psychological Comorbidities in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Actas Españolas De Psiquiatría. doi:10.62641/aep.v52i4.1559.

(18) Monda V, Villano I, Messina A, Valenzano A, Esposito T, Moscatelli F, Viggiano A, Cibelli G, Chieffi S, Monda M, Messina G. (2017). Exercise Modifies the Gut Microbiota with Positive Health Effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev. doi: 10.1155/2017/3831972.

(19) Khanijow V, Prakash P, Emsellem HA, Borum ML, Doman DB. (2015). Sleep Dysfunction and Gastrointestinal Diseases. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). PMID: 27134599; PMCID: PMC4849511. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4849511/

(20) Leigh, S. J., Uhlig, F., Wilmes, L., Clarke, G., & Cryan, J. F. (2023). The impact of acute and chronic stress on gastrointestinal physiology and function: a microbiota–gut–brain axis perspective. The Journal of Physiology, 601(20), 4491–4538. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP281951