Emily Brown

BSc (Human Nutrition)

Jump to:

Exercise, along with diet, is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for our overall well-being, and when performed regularly can reduce our risk of mortality by 35%.

To enjoy a great exercise, workout or even a long walk, and feel great afterwards, it is essential to properly fuel our body.

This is where we can choose to use carbohydrates (from wholefoods) or ketones (from healthy fats) as our preferred source of energy.

The question is, what does our body prefer and what does science and research say about the ever popular high-carb diet and the newly emerging ketogenic diet when it comes to exercise?

What are carbohydrates?

Like protein and fats, carbohydrates are a macronutrient made up of smaller sugar units, called ‘saccharides’.

Carbohydrates are present in most foods, with the highest quantities found in:

- fruit

- starchy vegetables

- bread

- cereals

- rice

- pasta

- legumes

- sugar

- juice

Carbohydrates can be simple or complex

During digestion, carbohydrates are broken down into glucose (a type of saccharide also known as blood sugar) and are either used immediately or stored as glycogen in our liver or muscles.[3]

Carbohydrates and performance

During exercise, our glycogen stores are the primary fuel source for working muscles, particularly as the exercise intensity increases.[4] These glycogen stores are limited and can easily be manipulated via carbohydrate intake.[5]

The effects of a high carbohydrate diet on performance depend on when the carbohydrates are consumed in relation to the time of exercise.

Before exercise, a high carbohydrate diet, also known as ‘carb loading’, is used to supersaturate muscle glycogen stores, and is effective at increasing performance for longer endurance events.[6]

Studies have found that performance can be increased by 7-20% from a high carbohydrate snack 60 min before the event.[7]

Carbohydrates ingested during exercise are shown to help maintain exercise intensity while decreasing the rates of tissue breakdown.[8] This helps delay fatigue and lengthen our workout.[5]

After exercise our glycogen stores are close to being depleted

It is recommended to consume 1 – 1.2 g of carbohydrates per kg of bodyweight every hour during the first 4 to 6 hours after exercise.[5] This helps to refuel our energy stores and helps with post exercise recovery.

Health benefits and health risks of using carbohydrates as fuel

Health benefits

Carbohydrates are an extremely useful source of fuel, and give many benefits, some of which we have shared below.

Carbs are a quality source of energy for our daily needs

Carbohydrates are our body’s main source of fuel. Choosing complex carbohydrates will provide energy for longer to keep us going.[3]

Carbs are the preferred food for the brain

The brain is very selective about what it can use as fuel, and depends on glucose as its main source of energy to function.[9]

RELATED — Diet and the Brain: Our brain on sugar

An important source of fibre

Carbohydrates are our main source of dietary fibre. A diet high in fibre can decrease our hunger cues, increase our digestive health, and reduce our risk of heart attacks.

Carbs help us to have a good night's sleep

Carbohydrate intake causes an increase in insulin, which in turn increases tryptophan production. Higher levels of tryptophan, an amino acid, is shown to improve our sleep quality.

RELATED — Magnesium (for a great night of sleep)

Health risks

Under-fuelling with carbs causes issues

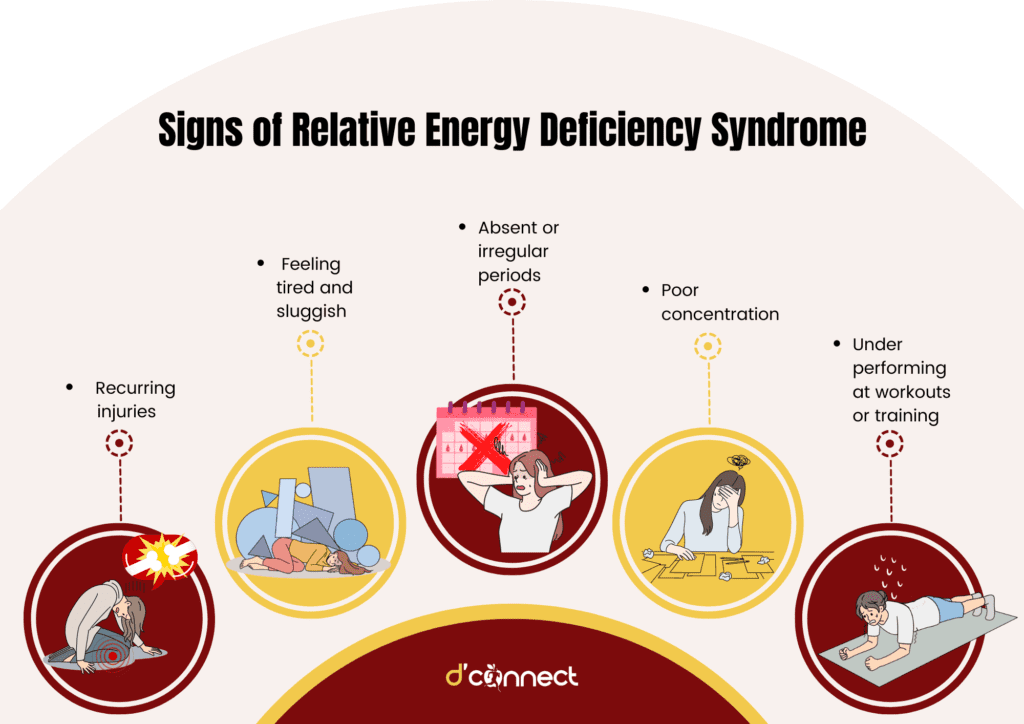

Under-fuelling with carbohydrates can put us at risk of developing Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome (RED-S).

Some symptoms of this syndrome include

- Recurring injuries that do not heal (e.g. stress fractures)

- Being tired, sluggish, and not recovering from workouts

- Absent or irregular menstrual periods

- Poor concentration, reduced interest, low mood

- Under performing in training and competition[2]

As a result of exercising on depleted glycogen, our body begins to break down muscle tissue to use as energy for the starving body and brain. Over time, this results in weakened tissues, psychological dysfunction, and hormonal irregularities.[2]

Problems that occur when consuming too many carbs

Gastrointestinal dysfunction

Significant number of endurance athletes (30-50%) experience stomach problems, such as diarrhoea or vomiting, and this can commonly be due to overconsumption of carbohydrates.[10]

Source: Parnell, J. Dietary restrictions in endurance runners to mitigate exercise-induced gastrointestinal symptoms. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. (2020).

However, this can be avoided by slowly increasing our carbohydrate intake over time, known as training our gut.

Water Retention

Excess carbohydrate intake can also lead to bloating and discomfort. When glucose is stored as glycogen, it binds with water molecules and increases water retention.

Weight Gain

Without a proportional increase in physical activity, consuming too much of carbohydrates can lead to a caloric-excess, and overtime cause weight gain. This is especially true with calorie-dense processed carbs, such as chips and sweets.[11]

High Blood Sugar

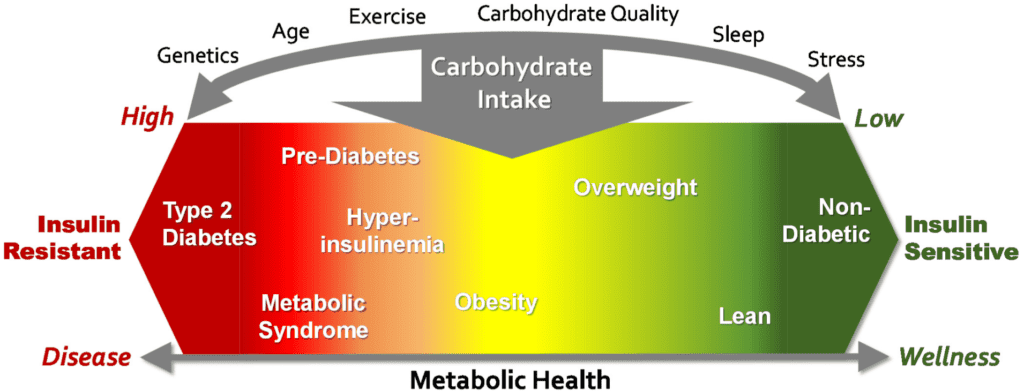

Overtime, an excessive consumption of processed carbohydrates will lead to elevated blood sugar levels, to which the body will then release insulin to counteract.

When sustained for a longer period of time, this can increase the risk of vascular blockages and type 2 Diabetes.[12]

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

Carbohydrate intake recommendations for performance

When following a high-carb diet for athletic performance, the American College of Sports Medicine has laid out carbohydrate guidelines to promote optimal performance. These are:

- When exercising less than 1hr a day, we should aim to consume 3-5 g of carbohydrates per kg of bodyweight

- When exercising around 1 hr a day, we should aim to consume 5-7 g of carbohydrates per kg of bodyweight

- When exercising more than 1 hr a day, we should aim to consume 6-12 g of carbohydrates per kg of bodyweight.[5]

Carbohydrate intake should be spread throughout the day, as well as focusing on adequate amounts before and after the workouts.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, there has been an emerging interest in swapping out carbohydrates for another fuel source – fats.

Could fat be the new super fuel for our muscles? We’ll look into this in more detail in the next part of the article.

What are ketones?

A ketogenic diet involves restricting the amount of carbohydrates consumed, which makes the body switch from using glucose as fuel to using ketone bodies.

Ketones are created by our liver from fat stores, via a process called ketosis.[13]

The ketogenic diet requires us to limit our intake of carbohydrates to 20-50g per day.

Intake of carbs should be less than 50g per day

Alternatively, <10% of our calories should come from carbohydrates, meaning that the more food we eat, and the more energy we burn, the more carbs we can consume.[13]

Ketogenic diet the right way (meat & dairy or plant-based keto)

Much of the distrust around the ketogenic diet is due to the misconception that involves increasing our consumption of meat and saturated fats, such as butter. This, then, would be the carnivore diet.

Ketogenic diet is mostly plant-based, and includes

- Healthy fats (avocado, nuts, seeds, coconut, flax, olive oil)

- Plant-based proteins (tofu, tempeh, beans)

- Non-starchy vegetables

- Limited amounts of low-sugar fruits

- Limited amount of animal protein (meat, eggs and dairy).[13]

Ketones and performance

The effects of ketones on exercise and athletic performance is a relatively new area of research.

Interest in the ketogenic diet and athletic performance is based on a theoretical idea of becoming metabolically flexible and adapting our body to be able to utilise whatever fuel is available.[14] So far, however, only a few controlled studies have been able to back this up.

When thinking about a keto diet, it is important to take into account the type of exercise we are doing.

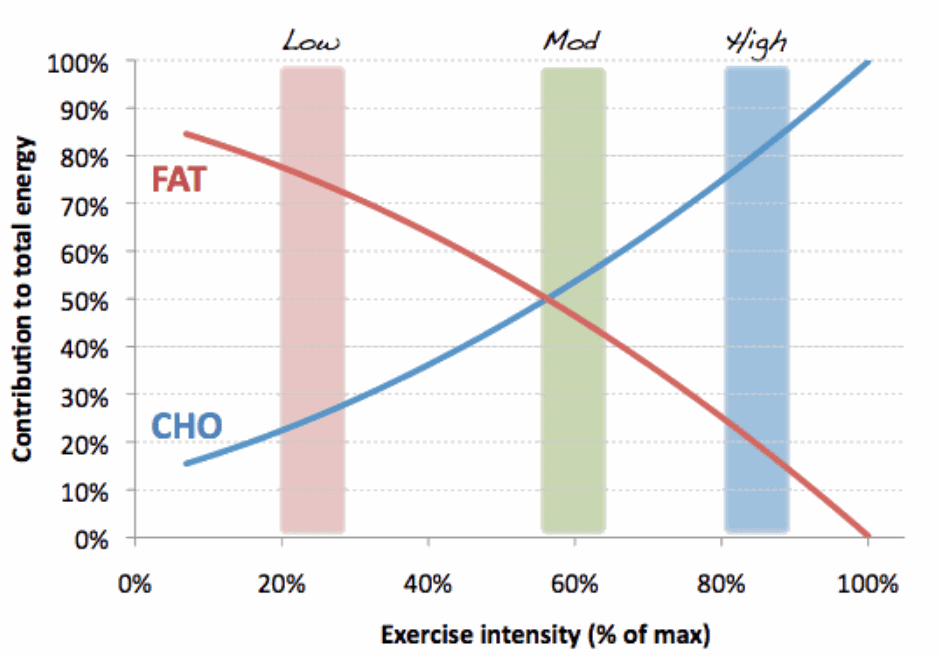

If our workouts are often high intensity, our body will rely more on carbohydrate stores, and a low-carb / high fat diet would be more suitable to those working out at a lower intensity.[15,16]

Source: The Science of Sport. Exercise and weight loss, Part 3: Fat

Ketones as fuel are more suitable for lower-intensity workouts

Endurance performance and ketones

When analysing ketones and their effects on athletic performance, the majority of the literature focuses on its effects on endurance.

Multiple systematic reviews, a total of 57 separate studies, have been conducted to analyse the impact of a ketogenic diet on endurance performance, all of which were unable to find significant effects on physical performance, aerobic capacity or oxygen consumption.[17]

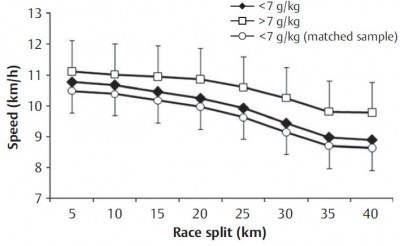

Burke et al., 2016 analysed the effects of a three week keto diet on endurance athletes’ performance, and found that it significantly increased their aerobic capacity (a measure of work intensity).

However, it also increased their oxygen demand during exercise, which negated any performance benefit.[18]

Strength performance and ketones

With regards to strength-based resistance exercises, systematic reviews have found that keto diet had no significant effect on strength and power.[19]

One systematic review found that this diet decreased individuals 1RM (one-rep-max) however this effect was not significant.[20]

Source: Source: Paoli, A., Grimaldi, K., D’Agostino, D., Cenci, L., Moro, T., Bianco, A., & Palma, A. (2012). Ketogenic diet does not affect strength performance in elite artistic gymnasts. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition

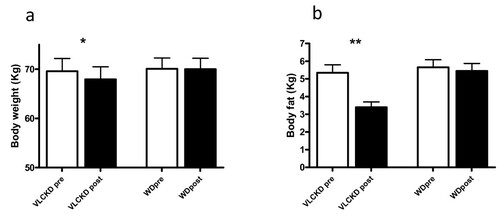

In one study, elite artistic gymnasts following a keto diet for one month reported a significant decrease in fat mass, however showed no change in strength or performance.[21]

Health benefits and health risks of using ketones as fuel

Health benefits of ketogenic diet

Ketogenic diet was first used for therapeutic purposes, some of which we mention below.

Drug-resistant epilepsy and ketones

Since 1920, the ketogenic diet has been used to treat drug-resistant epilepsy, and is still used for this reason today.

The mechanism of work is still disputed, but some possibilities include reduced glucose availability in the brain to fuel seizure activity, and the inhibition of neuron excitability by ketone bodies.[13,22]

RELATED — Diet and the Brain: Fats

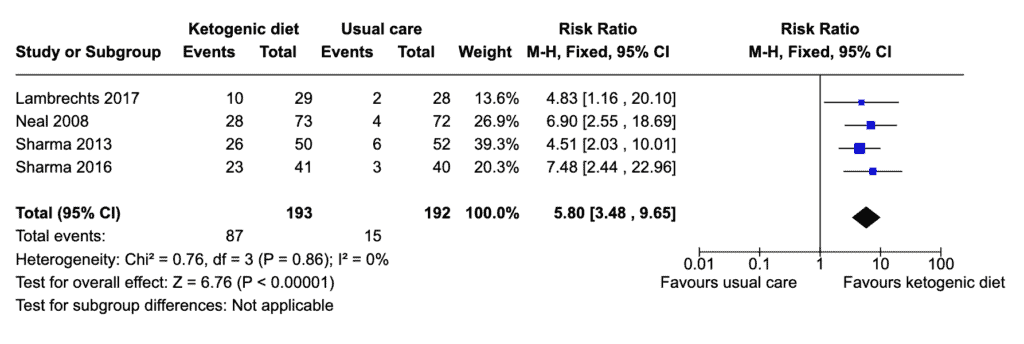

A systematic review found that when compared to a normal diet, a ketogenic diet is 5.8 times more likely to reduce the frequency of seizures by 50% in children with drug-resistant epilepsy.[23]

Source: Martin-McGill, K. J., Bresnahan, R., Levy, R. G., & Cooper, P. N. (2020). Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

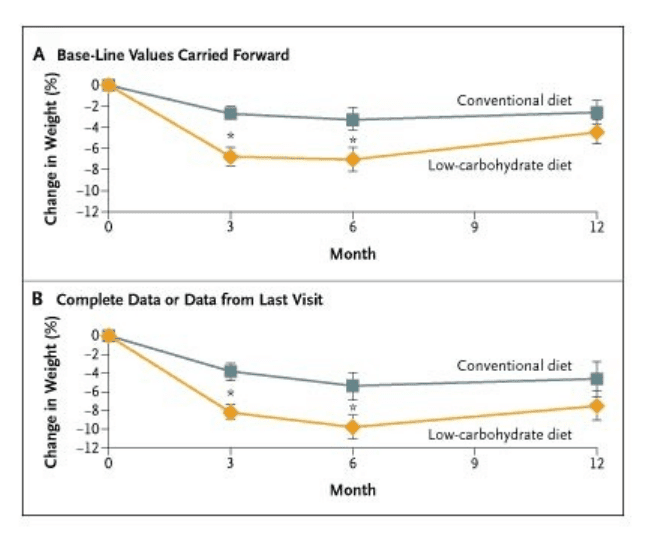

Weight Loss and ketogenic diet

Ketogenic diet has been widely shown to induce weight loss. Research shows that circulating ketones in the blood can reduce hunger signals and our desire to eat.[24]

However, research so far has found that this accelerated weight loss is rarely long-term, with no significant difference in weight loss when compared to an average diet.[25]

Source: Foster, G. D., et al. (2003). A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. New England Journal of Medicine.

Cardiovascular disease and ketogenic diet

When following a plant-based ketogenic diet, studies recorded a marked improvement in triglyceride and cholesterol levels, with

- total cholesterol levels decreasing, and

- HDL (healthy) cholesterol levels increasing

This suggests that a ketogenic diet might decrease the risk of cardiovascular diseases.[26]

Type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance

Research shows that in people with type 2 diabetes, following a keto diet for 56 weeks decreased blood glucose levels by 51% as well as reducing HbA1c.[27,28]

Restricting dietary carbohydrate levels can also improve or even reverse insulin resistance.[26]

Other benefits of ketogenic diet (research still in progress)

There is also new emerging research which shows promising effects of the ketogenic diet on

- reducing acne and skin issues

- treating neurological diseases (Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, sleep disorders, brain cancer, autism and multiple sclerosis)

- PCOS

- cancer[26,29]

However, research on these topics is still ongoing.

Health risks of ketogenic diet

The ketogenic diet has been known to come with certain health risks, and should always be used with caution.

During the adjustment period of starting the keto diet, our body may exhibit what is known as the ‘keto flu’. This is a set of symptoms often reported during the first four weeks.

Keto flu can occur as our body is weaned off sugar

RELATED — Sugar Addiction: Is Sugar “Cheap Cocaine”?

Due to “withdrawal” symptoms, some people experience headaches, fatigue, nausea, dizziness, constipation, decreased energy and heartbeat alterations.[30]

Other health risks that could result from the ketogenic diet include

- Raised LDL cholesterol, which can increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases (check the types of fats you are consuming)

RELATED — Types of Fats: Healthy and Unhealthy Dietary Fats

- Dyslipidemia and increased hypoglycaemic episodes in type 1 Diabetic patients

- Slowed growth, kidney stones, and bone fractures in children

- Irregular menstrual cycles in women

- Hypoproteinemia (low levels of protein in the blood) due to decreased protein intake

- Various vitamin deficiencies such as vitamins A, E, thiamine (vitamin B1), pyridoxine (vitamin B6), and folate (vitamin B9)

RELATED — Thiamine (Vitamin B1)

Source: Krauss, R.M, Alternative Dietary Patterns for Americans: Low-Carbohydrate Diets. Nutrients (2021).

The effects of low-carbohydrate diets on mortality risk are dependent on whether they rely on animal proteins and saturated fat or on plant protein and unsaturated fat, which can decrease the risk of mortality.[37]

Ketone intake recommendations for performance

Certain individuals, such as Dr. Peter Attia, a physician focusing on the “science of longevity”, and Zach Bitter, an ultra-marathoner and holder of the 100-mile American record, are advocates for the keto diet, attributing the diet to their sporting successes.

However, what works for certain individuals might not always work for all, and due to the limited and mixed results from scientific studies, no recommendations can be made as of yet.

High carbohydrate diet or ketogenic diet

A ketogenic diet focusing on plant proteins and unsaturated fats has shown to be a beneficial tool for

- weight loss

- glycaemic control

- epilepsy

- cholesterol levels

However, limited studies report these benefits in the long run, and with numerous health risks, it is not recommended to self-administer this diet without supervision from a health professional.

In terms of athletic performance, the keto diet showed no significant increases in endurance or strength based performance.

The International Society of Sports Nutrition states that the keto diet can impair both low and high intensity workouts, which suggests that it is best to fuel our workouts with high quality carbohydrates and proteins for now.

Related Questions

1. What to eat before a workout on a keto diet?

Regardless of what diet you are on, you need to fuel your body for exercise. On the keto diet, some options include greek yoghurt, cottage cheese, and keto-friendly protein bars.

Avoid large amounts of fat or protein directly before your workout, as this can cause stomach issues.[5]

2. Does exercise speed up weight loss in ketosis?

Exercise on a keto diet leads to short-term rapid weight loss as our glycogen stores are used.

However, this will be from water weight, as water tightly binds to glycogen, and weight loss will slow down as our glycogen stores are used up.[10]

As we remain in ketosis, our body will use fat stores as energy, and only reach out to glycogen reserves when they are readily available.

3. Can I work out while intermittent fasting?

Yes, you can work out while fasting, assuming your meals provide enough energy over the day. In fact, fasting is occasionally used by elite athletes to promote muscle adaptation during training.

However, if your workouts are high intensity or your energy levels drop, intermittent fasting may not be suitable if you are not properly re-feeding – meaning, consuming an adequate amount of food to sustain such activities.

The summer is slowly approaching and most of us are looking at getting back into shape. With nutrition only one part of having a great workout, it’s important that we are having a great exercise routine and guide as well.

You can find different Exercise Guides on our Activities and Performance page.

Emily is currently pursuing a Masters degree in Advanced Nutrition Practice. Her focus is on the role nutrition plays in physical activity and sport performance, while also gaining a better understanding of the nutritional treatments for Type 2 Diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, which are major contributors to health complications in New Zealand.

Emily’s interest in nutrition stems from her personal experience in sport at an elite level and the importance of diet regarding our performance and capabilities. Upon completion of her postgraduate studies, she intends to gain qualifications as a Registered Nutritionist and progress towards a career of a Sports Nutritionist.

Emily is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect.

References

(1) Samitz, G., Egger, M., & Zwahlen, M. (2011). Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of cohort studies. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(5), 1382-400. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/40/5/1382/658632?login=true

(2) Mountjoy, M., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Burke, L., Ackerman, K. E., Blauwet, C., Constantini, N., Lebrun, C., Lundy, B., Melin, A., & Meyer, N. (2018). International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 28(4), 316-331. Retrieved from https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/11/687

(3) Bagchi, D., Sreejayan, N., & Sen, C. K. (2018). Nutrition and enhanced sports performance: muscle building, endurance, and strength. Academic Press.

(4) Coyle, E. F., Jeukendrup, A. E., Wagenmakers, A. J., & Saris, W. H. (1997). Fatty acid oxidation is directly regulated by carbohydrate metabolism during exercise. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism, 273(2), E268-E275. Retrieved from https://journals.physiology.org/doi/pdf/10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.2.E268

(5) Thomas, D. T., Erdman, K. A., & Burke, L. M. (2016). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: nutrition and athletic performance. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(3), 501-528. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221226721501802X

(6) Karlsson, J., & Saltin, B. (1971). Diet, muscle glycogen, and endurance performance. Journal of applied physiology, 31(2), 203-206. Retrieved from https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/jappl.1971.31.2.203

(7) Hawley, J. A., & Burke, L. M. (1997). Effect of meal frequency and timing on physical performance. British Journal of Nutrition, 77(S1), S91-S103. Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/40EA6EC5BFDBA2BA817A43CF2279D03D/S0007114597000123a.pdf/effect_of_meal_frequency_and_timing_on_physical_performance.pdf

(8) Kerksick, C. M., Arent, S., Schoenfeld, B. J., Stout, J. R., Campbell, B., Wilborn, C. D., Taylor, L., Kalman, D., Smith-Ryan, A.E., Kreider, R.B. & Willoughby, D. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: nutrient timing. Journal of the international society of sports nutrition, 14(1), 33. Retrieved from https://jissn.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12970-017-0189-4#Abs1

(9) Mergenthaler, P., Lindauer, U., Dienel, G. A., & Meisel, A. (2013). Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function. Trends in neurosciences, 36(10), 587-597. Retrieved Aug 16, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900881/

(10) de Oliveira, E. P., Burini, R. C., & Jeukendrup, A. (2014). Gastrointestinal complaints during exercise: prevalence, etiology, and nutritional recommendations. Sports Medicine, 44(1), 79-85. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-014-0153-2#Sec5

(11) Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., Cai, H., Cassimatis, T., Chen, K. Y., Chung, S. T., Costa, E., Courville, A., & Darcey, V. (2019). Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell metabolism, 30(1), 67-77. e63. Retrieved Aug 12, 2022 from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1550413119302487

(12) Groeneveld, Y., Petri, H., Hermans, J., & Springer, M. P. (1999). Relationship between blood glucose level and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetic medicine, 16(1), 2-13. Retrieved Aug 12, 2022 from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00003.x

(13) Hartman, A. L., Gasior, M., Vining, E. P., & Rogawski, M. A. (2007). The neuropharmacology of the ketogenic diet. Pediatric neurology, 36(5), 281-292. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1940242/

(14) Aragon, A.A., Schoenfeld, B.J., Wildman, R., Kleiner, S., VanDusseldorp, T., Taylor, L., Earnest, C.P., Arciero, P.J., Wilborn, C., Kalman, D.S. & Stout, J.R. (2017). International society of sports nutrition position stand: diets and body composition. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1), 16. Retrieved Aug 12, 2022 from https://jissn.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12970-017-0174-y#citeas

(15) van Loon, L. J., Greenhaff, P. L., Constantin-‐Teodosiu, D., Saris, W. H., & Wagenmakers, A. J. (2001). The effects of increasing exercise intensity on muscle fuel utilisation in humans. The Journal of physiology, 536(1), 295-304. Retrieved Aug 12, 2022 from https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00295.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed

(16) Burke, L. M. (2021). Ketogenic low-CHO, high-fat diet: the future of elite endurance sport?. The Journal of physiology, 599(3), 819-843. Retrieved Aug 12, 2022 from https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1113/JP278928

(17) Cao, J., Lei, S., Wang, X., & Cheng, S. (2021). The effect of a ketogenic low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet on aerobic capacity and exercise performance in endurance athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients, 13(8), 2896.

(18) Burke, L. M., Ross, M. L., Garvican‐Lewis, L. A., Welvaert, M., Heikura, I. A., Forbes, S. G., & Hawley, J. A. (2017). Low carbohydrate, high fat diet impairs exercise economy and negates the performance benefit from intensified training in elite race walkers. The Journal of physiology, 595(9), 2785-2807. Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1113/JP273230

(19) Kang, J., Ratamess, N. A., Faigenbaum, A. D., & Bush, J. A. (2020). Ergogenic properties of ketogenic diets in normal-weight individuals: A systematic review. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 39(7), 665-675. Retrieved Jul 16, 2022 from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07315724.2020.1725686

(20) Koerich, A. C. C., Borszcz, F. K., Thives Mello, A., de Lucas, R. D., & Hansen, F. (2022). Effects of the ketogenic diet on performance and body composition in athletes and trained adults: a systematic review and Bayesian multivariate multilevel meta-analysis and meta-regression. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 1-26.

(21) Paoli, A., Grimaldi, K., D’Agostino, D., Cenci, L., Moro, T., Bianco, A., & Palma, A. (2012). Ketogenic diet does not affect strength performance in elite artistic gymnasts. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 9(1), 34. Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1186/1550-2783-9-34

(22) D’Andrea Meira I, Romão TT, Pires do Prado HJ, Krüger LT, Pires MEP, da Conceição PO. Ketogenic Diet and Epilepsy: What We Know So Far. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:5. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6361831/

(23) Martin-McGill, K. J., Bresnahan, R., Levy, R. G., & Cooper, P. N. (2020). Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (6). Retrieved from https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001903.pub5/pdf/full

(24) Gibson, A. A., Seimon, R. V., Lee, C. M., Ayre, J., Franklin, J., Markovic, T., Caterson, I., & Sainsbury, A. (2015). Do ketogenic diets really suppress appetite? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews, 16(1), 64-76. Retrieved from https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/handle/2123/16246/Gibson_Obes.Rev_2015.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

(25) Nordmann, A. J., Nordmann, A., Briel, M., Keller, U., Yancy, W. S., Brehm, B. J., & Bucher, H. C. (2006). Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Archives of internal medicine, 166(3), 285-293. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/409791

(26) Paoli, A., Rubini, A., Volek, J. S., & Grimaldi, K. A. (2013). Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. European journal of clinical nutrition, 67(8), 789-796. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3826507/

(27) Dashti, H. M., Al-Zaid, N. S., Mathew, T. C., Al-Mousawi, M., Talib, H., Asfar, S. K., & Behbahani, A. I. (2006). Long term effects of ketogenic diet in obese subjects with high cholesterol level. Molecular and cellular biochemistry, 286(1), 1-9. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sami-Asfar/publication/7129732_Long_Term_Effects_of_Ketogenic_Diet_in_Obese_Subjects_with_High_Cholesterol_Level/links/02bfe5111cfff029c7000000/Long-Term-Effects-of-Ketogenic-Diet-in-Obese-Subjects-with-High-Cholesterol-Level.pdf

(28) O’Neill, B., & Raggi, P. (2020). The ketogenic diet: Pros and cons. Atherosclerosis, 292, 119-126. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021915019315898

(29) Stafstrom, C. E., & Rho, J. M. (2012). The ketogenic diet as a treatment paradigm for diverse neurological disorders. Frontiers in pharmacology, 3, 59. Retrieved Jul 16, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3321471/

(30) Bostock, E., Kirkby, K. C., Taylor, B. V., & Hawrelak, J. A. (2020). Consumer reports of “keto flu” associated with the ketogenic diet. Frontiers in nutrition, 20. Retrieved Jul 16, 2022 from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2020.00020/full?luicode=10000011&lfid=1076037393687925&u=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.frontiersin.org%2Farticles%2F10.3389%2Ffnut.2020.00020%2Ffull

(31) Bueno, N. B., de Melo, I. S. V., de Oliveira, S. L., & da Rocha Ataide, T. (2013). Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Nutrition, 110(7), 1178-1187. Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/verylowcarbohydrate-ketogenic-diet-v-lowfat-diet-for-longterm-weight-loss-a-metaanalysis-of-randomised-controlled-trials/6FD9F975BAFF1D46F84C8BA9CE860783

(32) Leow, Z. Z. X., Guelfi, K. J., Davis, E. A., Jones, T. W., & Fournier, P. A. (2018). The glycaemic benefits of a very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet in adults with Type 1 diabetes mellitus may be opposed by increased hypoglycaemia risk and dyslipidaemia. Diabetic Medicine, 35(9), 1258-1263. Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dme.13663?casa_token=OPbnl4tPi-0AAAAA%3ATzixymvbVzPTmgzYuQfDe3Ft5d45fRi4cYsulUTQ4GRUabqvDtkY0EwxZpTZksnfXica5FnnatyZq4HC

(33) Groesbeck, D. K., Bluml, R. M., & Kossoff, E. H. (2006). Long-term use of the ketogenic diet in the treatment of epilepsy. Developmental medicine and child neurology, 48(12), 978-981. Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2006.tb01269.x

(34) Mady, M. A., Kossoff, E. H., McGregor, A. L., Wheless, J. W., Pyzik, P. L., & Freeman, J. M. (2003). The ketogenic diet: adolescents can do it, too. Epilepsia, 44(6), 847-851. Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.57002.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed

(35) Batch, J. T., Lamsal, S. P., Adkins, M., Sultan, S., & Ramirez, M. N. (2020). Advantages and disadvantages of the ketogenic diet: a review article. Cureus, 12(8). Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://www.cureus.com/articles/37088-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-the-ketogenic-diet-a-review-article

(36) Freedman, M. R., King, J., & Kennedy, E. (2001). Executive Summary. Obesity Research, 9(S3), 1S-5S. Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1038/oby.2001.113

(37) Shan, Z., Guo, Y., Hu, F. B., Liu, L., & Qi, Q. (2020). Association of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets with mortality among US adults. JAMA internal medicine, 180(4), 513-523. Retrieved Jul 21, 2022 from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/2759134