Molly Farrell

BSci majoring in Psychology, PGDp in Health Science

Note — The article was checked and updated August 2023.

Anxiety in today’s modern society is becoming more widespread and it is one of the most common mental illnesses in the world with 275 million people or 4% of the total population suffering from it.

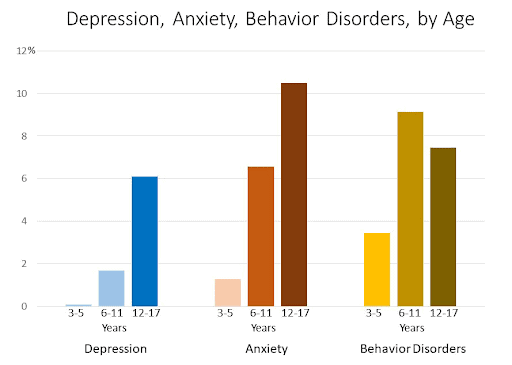

The highest rise in anxiety is among teenagers. Anxiety among children and adolescents has been on the rise for decades and our predisposal has been widely speculated.

What is fueling this generational incline and what can we learn moving forward?

Has anxiety increased overtime?

In simple terms, absolutely. In the early 2000s, pioneering this research, Jean Twenge took this question to the test.

Compiling the results of 170 studies from the 1950’s onwards, Twenge measured the anxiety levels of 50,000 children and college students.[1] The linkages between social change and mental health are substantial and the results speak volumes.

In fact, the differences are so significant that the average level of anxiety among a child in the 90’s was similar to the average psychiatric patient in the 50’s.

As Twenge indicates, high stress levels have become a rite of passage among school students and young adults.[1]

What are the reasons for growth in anxiety?

We know our social fabric is forever changing. Twenge’s analysis captured these changes, evidently unpacking the causes and effects of anxiety through a socio-cultural lens. The data shows that social connectedness and high environmental threats are the largest influences on anxiety and can be accountable for 20% of the growth.[1]

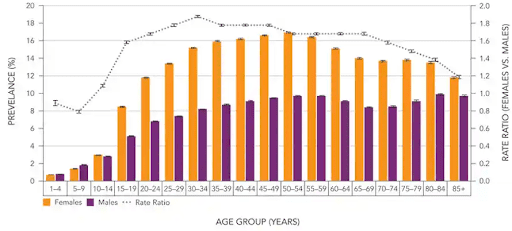

In the chart below we can see the prevalence of anxiety between different age groups and males and females.

This growing force prioritises self-direction and independence, which in itself is not necessarily a negative feature. However, when combined with high divorce rates, the commonality of living alone and the decreased likelihood to join groups or clubs, we are faced with problematic points of influence.[2]

In more recent years these are also exacerbated by our reliance on social media. But unfortunately these platforms are not a viable substitute.[4]

Sure, greater autonomy can achieve greater challenges and generate excitement in our lives. It offers more choices, but it also invites isolation thus increased threat and higher levels of anxiety.[1]

The freedom to decide can be so overbearing to the extent we are paralyzed by those choices.[4]

Stress and anxiety - are they connected?

Interestingly, the potency of stress and anxiety is relative. Humans feel less deprived when others are equally stressed and anxious.[2]

RELATED — Understanding Stress: The Silent Killer

This shows us how our anxiety is heavily influenced by our own perceptions, enabling us to have more control on our thoughts than we may think.

We are living in a time where perceived environmental threats are peaking, but collective protection can balance our anxious thoughts and feelings and promote our sense of safety.[2]

RELATED — Anxiety and Smoking: How it affects our Mental Health

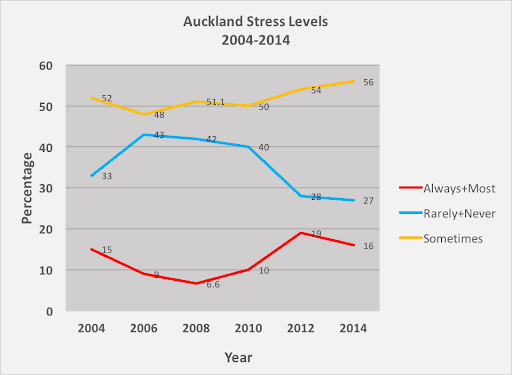

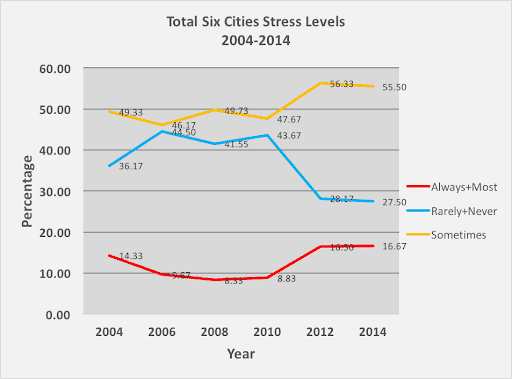

The Quality of Life Project which began in 1999, captured some of these areas in their longitudinal study, describing Ten Years of Stress in New Zealand. In the charts below, we can see the collated data. These results further confirm the growth of stress we continuously accept.[5]

Our brains are most fragile in our developing years and childhood is the time of greatest societal influence. Many of us do not realize we carry our inner child for life. Opportunely, how we nurture a child’s stress will influence their resilience to stress throughout adulthood.[6]

RELATED — Video Game Addiction: “Teenagers” and Gaming

Children and adolescents perceive more danger in the world and without a sense of community protection become prone to panic.

Stress in childhood influences our resilience later in life

To conclude, the mirroring rise of individualism and anxiety poses a great threat to the health of our minds. We need to reframe how we think about our social capital, our human interaction and connectedness; we need to view them as tools of protection. Until people feel both safe and connected to others, anxiety levels are to remain high.

Mental Health and Wellness Advocate

With extensive experience as a mental health support worker, Molly knows first hand the impact our mind can have on our physical, emotional and social wellbeing. She has completed a Bachelor’s of Science, majoring in Psychology, and a postgraduate diploma in Health Science, which gives her an opportunity to combine theoretical knowledge with practice.

Molly’s goal and focus is to provide others with education and awareness on how we can improve our mental wellness and of those around us.

References

(1) Twenge, J.M. (2000). The Age of Anxiety? Birth Cohort Change in Anxiety and Neuroticism, 1952-1993. Journal of Personality and Social Anxiety, 79(6),1007-1020. https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/psp7961007.pdf

(2) Santos, H.C., Varnum, M.E.W & Grossmann,I. (2017). Global Increases in Individualism. Psychological Science,28(9),1228-1239. https://psyarxiv.com/hynwh/

(3) Schwartz, B. (2000). Self-determination: The tyranny of freedom. American Psychologist, 55,79-88. https://www.swarthmore.edu/SocSci/bschwar1/self-determination.pdf

(4) Waszczuk, M.A., Zavos, H.M & Eley, T.C. (2013). Genetic and environmental influences on the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and anxiety subscales in children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(5),475-484. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250924000_Genetic_and_environmental_influences_on_relationship_between_anxiety_sensitivity_and_anxiety_subtypes_in_children

(5) Puddlegum. (2016). Ten years of stress in New Zealand. The Political Scientist. https://www.thepoliticalscientist.org/ten-years-of-stress-in-new-zealand/

(6) Twenge, J.M. (2019). More Time on Technology, Less Happiness? Associations Between Digital-Media Use and Psychological Well-Being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(4):372-379. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0963721419838244