Margaux M. Tolley

MSc (Neuroscience), PgDipSci (Neuroscience), BSc (Neuroscience)

Neurotransmitters are the body’s chemical messengers that transmit signals from one neuron (nerve cell) to the next target cell across a tiny gap called the synapse. These target cells can be another neuron, a muscle cell, or a gland cell.

Neurotransmitters are essential for all functions of the nervous system, regulating everything from breathing and heartbeat to complex cognitive processes like learning, mood, and memory.

What are neurons?

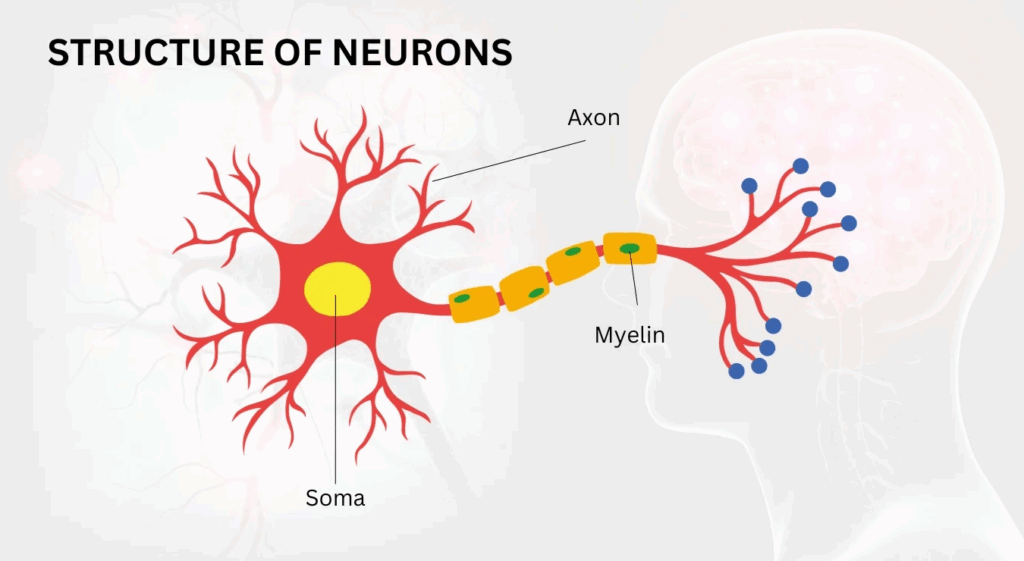

Neurons are excitable cells. Their basic anatomy is optimized to transmit electrical signals along their body. The main parts of the neuron are:

- Dendrites (projections from the soma)

- Soma (cell body)

- Axon (projection from soma that transmits action potentials to nerve terminal)

- Myelin sheath (membrane that wraps around the axon)

- Nerve terminal or ending

At the nerve end, the neuron will either make direct contact or come in close proximity with another cell or other neurons’ dendrites. The region of close proximity is referred to as the synapse.

A neuron is a primary functional unit of the nervous system

Neurons transmit signals to one another either through direct electrical transmission, when they make direct contact with one another, or through chemical transmission via neurotransmitters at the synapse.

For the purpose of this article, we will focus on chemical transmission via neurotransmitters.

What are neurotransmitters?

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that have a variety of roles in the body. Purves et al. (2001) define specific criteria for a molecule to be classed as a neurotransmitter, the molecule must be:

- present in the neuron sending the signal (presynaptic)

- released in response to an action potential

- and must bind to specific receptors present on the neuron receiving the signal (post-synaptic)[1]

Up until the early 20th century, most scientists still believed neurons only communicated with one another through electrical transmission.

Chemical transmission was only a theory until the 1920s, when the researcher, Otto Loewi (1973-1961), demonstrated chemical transmission for the first time in the peripheral nervous system.

Loewi stimulated the vagus nerve of a frog’s heart resulting in a lowered heart rate. He then transferred the fluid from the first heart onto a second heart, with no vagus nerve attached, and found the second heart also slowed its heart rate.

Loewi determined that the vagus nerve from the first heart released a molecule, which he termed “vagusstoff” (German: “vagus stuff”) which slowed down the heart rate in both frog hearts. Today we know vagusstoff was the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

The first to show chemical transmission within the central nervous system was Australian neurophysiologist, Sir John Eccles (1903-1997).

Eccles had been at odds with the chemical transmission theory, and he himself advocated for the electrical transmission theory. With his team, Jack Coombs and Lawrence Brook, at the University of Otago in Dunedin, they designed a highly sensitive microelectrode that both stimulated and measured changes in the internal voltage of a neuron.

In August 1951, they discovered that the level of intracellular inhibition could not be electrically induced. Eccles swiftly changed gears and became an advocate for the chemical transmission theory, altering his career path and his later experiments which awarded him the Nobel prize.

How do neurotransmitters work?

Neurons have a resting membrane potential of -70mV, meaning the inside of the cell is negatively charged compared to the fluid outside the cell.

There is a certain voltage threshold that must be met for an action potential to be activated. When the threshold is met, an action potential is triggered and travels down the axon to the nerve ending, resulting in local depolarization of the nerve terminal and the subsequent release of neurotransmitters.

Neurotransmitters pass through the synapse and bind to receptors on the postsynaptic cell or cells. Depending on the kind of neurotransmitter (excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory), they will have vastly different effects on the target neuron.

In general, neurotransmitters once bound to a receptor, elicit their effects and are then either

- broken down by enzymes

- taken back up by the presynaptic neuron, or

- diffuse in the surrounding fluid

The nerve terminal then repolarises, returns to -70mV, and the neurotransmitters that were taken back up are re-stored for later use.

Function of neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters allow us to think, eat, feel, move, communicate and more. Malfunction of any neurons’ receptors, release of neurotransmitters, or binding capability can have major impacts on our daily function and perception.

Neurotransmitters can be

- excitatory

- inhibitory

- modulatory

When an excitatory neurotransmitter, such as glutamate, binds to receptors on a postsynaptic neuron, it will cause the membrane to become less negatively charged, increasing the likelihood of an action potential to be fired.

Excitatory neurotransmitters allow neurons to communicate and rapidly transmit a signal through a system, like neuronal Chinese whispers. There is a famous saying in neuroscience, “neurons that fire together, wire together” meaning the more a signal is transmitted from one neuron to the next, the more solidified the connection (the synapse) becomes.[2]

This is the process of learning or practicing a skill, like riding a bike. Eventually, you no longer need to focus on how to balance on two wheels and can simply hop on your bike and go.

Inhibitory neurotransmitters, such as GABA, decrease the likelihood of an action potential to be fired. Once they bind to a receptor on the cell membrane, the cell membrane hyperpolarises or becomes more negative than the resting membrane potential, making it harder for the neuron to reach the threshold to fire an action potential.

Inhibitory signals are important to shut off signals and dampen activity. Too much excitement can lead to seizures or anxiety. They can fine tune the signals being sent through the brain, allowing more precision in the timing, quality and balance of the signal.

Lastly, there are modulatory neurotransmitters. Unlike the classic excitatory or inhibitory neurotransmitter, modulatory transmitters, like acetylcholine or dopamine, are much slower acting and can influence the activity of a population of neurons.

Modulatory neurotransmitters alter the responsiveness of the neuron to other neurotransmitters rather than directly causing excitation or inhibition.

These effects are much longer lasting, from a few seconds to hours. They regulate the activity of a system rather than an individual signal. These neurotransmitters are important for forming memories, learning, and motor control.

Types of neurotransmitters

Currently, there are well over 100 distinct neurotransmitters with the exact number unknown. Neurotransmitters are organised into six different categories depending on the functional role and the chemical structure.

These categories are

- amino acid neurotransmitters

- monoamines

- peptide neurotransmitters (neuropeptides)

- purine neurotransmitters

- gasotransmitters

- lipid-derived neurotransmitters

Amino Acid neurotransmitters

Amino acid neurotransmitters are the most abundant within the central nervous system. Structurally, they have both positive (cationic) and negative (anionic) charges at either end of their molecular structure.[3]

There are both excitatory and inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitters.

Examples of excitatory amino acid neurotransmitters are

- glutamate (which is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain)

- aspartate (often co-released with glutamate and fine-tunes circuitry)

Examples of inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitters are

- GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid; which is the main inhibitory transmitter in the brain)

- glycine (which is the main transmitter in the spinal cord)

Monoamines

Monoamine neurotransmitters are classed based on the same chemical structure. They share an aromatic ring connected to an amino group by a carbon-carbon chain.

There are three types of monoamines. These are

- catecholamines (which include adrenaline, noradrenaline, and dopamine)

- imidazolamines (such as histamine)

- indolamines (including serotonin)

Each monoamine neurotransmitter type differs in aromatic ring, precursor amino acid, binding receptor, function in the brain and enzymatic pathway.

For example, catecholamines contain a catechol ring and are synthesized from tyrosine while indolamines contain an indole ring and are synthesized from tryptophan. Lastly, imidazolamines contain an imidazole ring and are synthesized from histidine.

Monoamine neurotransmitters regulate and modify the brain

In general, monoamine neurotransmitters regulate and modify brain systems over longer periods of time, implementing them in motivation, mood, and arousal levels (sleep or wakefulness).

Neuropeptides

Neuropeptides are small chain amino acids and are some of the most abundant signaling molecules in the nervous system.

Neuropeptides can act as both neurotransmitters or hormones. As a neurotransmitter, neuropeptides are primarily neuromodulators. They are involved in the regulation of

- emotions

- appetite

- stress

- social bonding

- sleep

Dysregulation of neuropeptides has been linked with disorders like depression, obesity, stress, and anxiety.

Examples of neuropeptides include endorphins and oxytocin.

Purine neurotransmitters

Purine neurotransmitters historically have been very difficult to identify. This is due to their presence in all cells and the numerous cellular pathways which produce them.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which you may know as the energy molecule, was the first purine neurotransmitter to be discovered in the central nervous system in the 1950s.

ATP can act as both a rapid excitatory neurotransmitter or a slow neuromodulator.

Other purine neurotransmitters include

- adenosine

- adenosine diphosphate

- guanine-based purines

Unlike standard neurotransmitters which have dedicated signaling roles, purine neurotransmitters when released transmit both the signal and the metabolic state of the presynaptic neuron. They also connect the central nervous system with numerous other systems in the body such as the immune system, and are released from both glia and neurons.

In general, purine neurotransmitters are universal signaling molecules that can directly excite a neuron or act as a neuromodulator, fine-tuning signals.

Gasotransmitters

Gasotransmitters are classed based on specific criteria: they are small, produced endogenously within the cell, and are gaseous molecules which can freely permeate cell membranes. There are three primary gasotransmitters. These are

- nitric oxide

- hydrogen sulfide

- carbon monoxide

Each plays a major physiological, homeostatic role and the balance of each is very important. Gasotransmitters primarily modulate synaptic changes, altering the responsiveness of ion channels and affecting a neuron’s excitability, indirectly influencing the likelihood for a neuron to release neurotransmitters. They play a role in processes such as memory formation and learning.

Lipid-derived neurotransmitters

Lipid-derived neurotransmitters are classed under unconventional messengers along with gaseous neurotransmitters.

Lipid-derived neurotransmitters generally act as modulatory neurotransmitters, adjusting neuronal communication and shaping memory, stress response, and pain.

Endocannabinoids are some of the most studied and best characterized among the lipid-derived neurotransmitters.

They are produced when needed from phospholipid precursors in the postsynaptic membrane and generally work retrogradely. They travel from the postsynaptic cell to the presynaptic terminal to regulate neurotransmitter release.

Hormone vs Neurotransmitter

Neurotransmitters and hormones have similar functions, and molecules can be both a hormone and a neurotransmitter. However, scientifically, neurotransmitters and hormones are distinct from one another.

Hormones control functions like growth, how our body responds to stress and metabolism. Unlike neurotransmitters which affect cells locally and have specific targets, hormones are much slower acting with longer lasting effects; they are released from endocrine glands such as the pituitary, adrenal gland or the gonads.

Hormones are released into the bloodstream and travel to various regions in the body to elicit their effect. After eliciting their action, hormones are broken down by enzymes produced from certain organs, like the liver or the kidneys. This is an essential step for hormonal functioning so hormone concentration levels do not become toxic.

Furthermore, some molecules, like epinephrine (adrenaline) or dopamine, can be a neurotransmitter or a hormone depending where the molecule is released.

For example, as a neurotransmitter, dopamine neurons have vast connections throughout the brain and play roles in motor control, motivation, and executive functioning. As a hormone, dopamine is released from a region called the hypothalamus into the bloodstream and travels to the pituitary gland, constantly reducing the release of prolactin.

Neurotransmitters are pivotal to neuroscience. They are one mechanism for how neurons communicate to one another. Neuronal communication allows us to feel, think, eat, move and much more.

Margaux is a neuroscientist with a strong academic background and hands-on experience in research, specializing in muscle physiology, electrophoresis, and protein analysis. Her Master’s research focused on identifying key protein…

If you would like to learn more about Margaux, see Expert: Margaux M. Tolley.

References

(1) Purves, D., Augustine, G. J., Fitzpatrick, D., Katz, L. C., LaMantia, A.-S., McNamara, J. O., & Williams, S. M. (2001). What Defines a Neurotransmitter? In Neuroscience. 2nd Edition. Sinauer Associates.

(2) Hebb, D. O. (2012). The organization of behavior : a neuropsychological theory. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

(3) Tiedje, K. E., Stevens, K., Barnes, S., & Weaver, D. F. (2010). β-Alanine as a small molecule neurotransmitter. Neurochemistry International.