Chris Veitch

PhD Physiology, BBiomedSc (Hons)

Power naps are becoming increasingly popular within workplaces and within popular science.

Taking a short 15-20 minute nap is recommended by Waka Kotahi for reducing driver fatigue as a key part of their road safety campaigns, and is even recommended by big name companies such as Google and NASA as a way to improve employee performance.[1,2]

In this article, we will learn more about the impact of short naps on brain health and function.

Cognition, memory and alertness

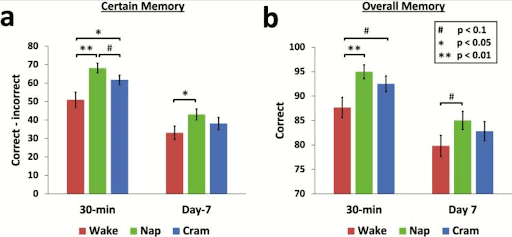

Researchers have found that a nap may aid in the “cramming of knowledge” prior to an exam. Participants were divided into three groups and studied for 90 minutes, following which:

- nap group would have a 60 minute nap

- cram group would continue studying

- wake group would take a 60 minute break[3]

Participants in the nap group were shown to have significantly greater correct answers in both the initial exam and an exam a week later, than participants, in both groups, who stayed awake.[3]

This suggests that napping provides a benefit to memory to a level equivalent, and potentially greater than cramming alone.

Even outside the context of pre-exam cramming, a daytime nap has been shown to be helpful in improving memory. A 2020 study showed that individuals who had a 90 minute midday nap (following a night of normal, unrestricted sleep) had greater recall of learned words in a task compared to individuals who stayed awake following learning these words.[4]

Daytime nap helps in improving memory

These researchers also found that those who napped showed increased activation of a brain area known as the hippocampus, which is known to be involved with learning and memory.[4]

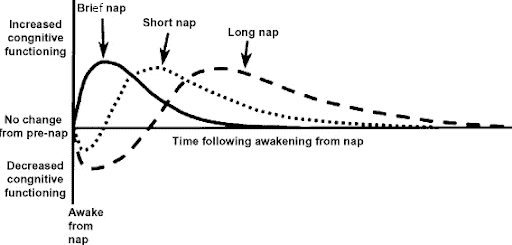

A 2010 review article examining nap duration and cognition collated data on the effects of:

- brief naps (~10 minutes)

- short naps (~30 minutes)

- long naps (~2 hours)

on sleep inertia, which is the poor cognition and lowered alertness that often follows wake from a long sleep.[5]

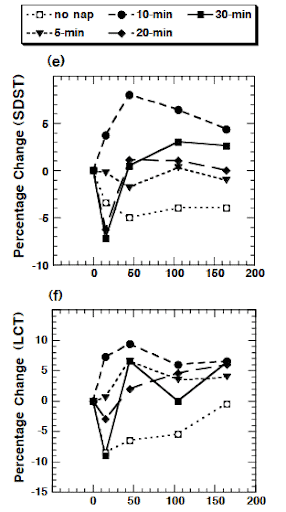

- no nap

- 5-minute nap

- 10-minute nap

- 20-minute nap

- 30-minute nap

Longer naps did still show improvements in the measured outcomes, but showed a drop in performance immediately following the nap lasting around 30 minutes before showing an improvement in the measured tasks.[6]

These longer naps are able to improve cognition late in the day when we often feel tired and less productive, situations when we might otherwise turn to caffeine to help with concentration.

A 2011 study showed that individuals who had a 100-minute nap opportunity performed significantly better in a memory task at 6.00pm compared to individuals who stayed awake during the day.[7]

Neurological conditions

Apart from general cognition, we also may wonder if power naps are able to protect against development of brain disease such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Sleep deprivation is known to increase the accumulation of amyloid-β within the brain, with accumulation and development of these amyloid-β plaques being implicated in Alzheimer’s disease development.[8,9]

There is some debate within the scientific community of whether daytime naps are protective, or may increase the risk of cognitive decline such as Alzheimer’s disease.

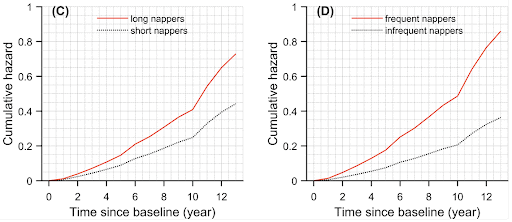

Researchers found that older individuals (~80 years old on average) who napped for >1hr per day (long nappers) were at greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s than short nappers.

Increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s was also associated with being a frequent napper (napping once or more per day).[10]

This result has been echoed in further studies showing that older men who napped for >120 minutes per day were 66% more likely to develop cognitive impairment within 12 years, compared to those who napped <30 minutes per day.[11]

Another research group found in 2012 that any duration of napping was associated with increased cognition, and that simply <6.5 hours of nocturnal sleep and excessive daytime sleepiness was instead associated with cognitive impairment.[12]

It has been noted in previous studies that individuals who had poor quality sleep did not have an increased risk of cognitive decline, so perhaps naps in this case are just making up for an overall lack of sleep?

The research around this topic is still developing, but given the effects of sleep deprivation on amyloid-β accumulation within the brain, it stands to reason that if you are suffering from sleep restriction, a daytime nap could have some benefits to help protect against Alzheimer’s development.

Mental Health

Mental health and sleep disorders often go hand in hand, with 80% of patients who suffer from depression also suffering from insomnia.[13]

Anxiety is also known to impact sleep, with sufferers often being unable to fall asleep due to worry and fear, which in some cases can lead to loss of sleep.[14]

RELATED — Introduction to Anxiety: Know what you are dealing with (Part 1)

Interestingly, daytime napping has been associated with an increased risk of depression, although this may be influenced by the fact that those with depression may be using naps to recover from a poor night-time sleep.[15]

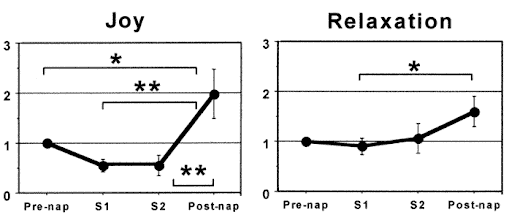

Napping has been shown to improve mood following exposure to stress, and individuals who took a short afternoon nap were noted to exhibit significantly heightened levels of both joy and relaxation.[16,17]

A 2004 study of elderly Japanese individuals examined the effects of a post-lunch nap and moderate evening exercise on general mental health and other metrics.

The researchers found that this intervention of both exercise and a 30-minute nap improved general mental health and nocturnal sleep quality.[18]

Short naps can increase feeling of joy

It is hard to say exactly what proportions the exercise and nap contributed to this effect, but the results do suggest daytime naps could be a useful way to improve mental health.

No such studies as of the time of writing have looked specifically at these conditions, but a short power nap could be a good idea to both help recuperate from poor night-time sleep due to anxiety and depression, and improve daytime mood based on the results from the above studies.

RELATED — Depression Signs and Symptoms: Stop the downward spiral in time (Part 1)

For similar articles, please check our section on Sleep.

Chris is currently working as a clinical physiologist, specialising in sleep medicine. He is also currently studying towards his Postgraduate Diploma in Medical Technology endorsed in sleep medicine…

If you would like to learn more about Chris, see Expert: Chris Veitch.

References

(1) Merkher, Y., Kontareva, E., Alexandrova, A., Javaraiah, R., Pustovalova, M., & Leonov, S. (2023). Anti-Cancer Properties of Flaxseed Proteome. Proteomes, 11(4), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes11040037

(2) Truan, J.S., Chen, J.-M. and Thompson, L.U. (2010), Flaxseed oil reduces the growth of human breast tumors (MCF-7) at high levels of circulating estrogen. Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 54: 1414-1421.

(3) Chen, J., Stavro, P. M., & Thompson, L. U. (2002). Dietary flaxseed inhibits human breast cancer growth and metastasis and downregulates expression of insulin-like growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor. Nutrition and cancer, 43(2), 187–192.

(4) Pandey, P., Khan, F., Alshammari, N., Saeed, A., Aqil, F., & Saeed, M. (2023). Updates on the anticancer potential of garlic organosulfur compounds and their nanoformulations: Plant therapeutics in cancer management. Frontiers in pharmacology, 14, 1154034. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1154034

(5) Petrovic, V., Nepal, A., Olaisen, C., Bachke, S., Hira, J., Søgaard, C. K., Røst, L. M., Misund, K., Andreassen, T., Melø, T. M., Bartsova, Z., Bruheim, P., & Otterlei, M. (2018). Anti-Cancer Potential of Homemade Fresh Garlic Extract Is Related to Increased Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Nutrients, 10(4), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040450

(6) Modem, S., DiCarlo, S. E., & Reddy, T. R. (2012). Fresh Garlic Extract Induces Growth Arrest and Morphological Differentiation of MCF7 Breast Cancer Cells. Genes & Cancer, 3(2), 177-186. doi:10.1177/1947601912458581

(7) Lučić, D., Pavlović, I., Brkljačić, L., Bogdanović, S., Farkaš, V., Cedilak, A., Nanić, L., Rubelj, I., & Salopek-Sondi, B. (2023). Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Kale (Brassica oleracea L. Var. acephala DC.) and Wild Cabbage (Brassica incana Ten.) Polyphenolic Extracts. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 28(4), 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28041840

(8) Rachwał, K., Niedźwiedź, I., Waśko, A., Laskowski, T., Szczeblewski, P., Kukula-Koch, W., & Polak-Berecka, M. (2023). Red Kale (Brassica oleracea L. ssp. acephala L. var. sabellica) Induces Apoptosis in Human Colorectal Cancer Cells In Vitro. Molecules, 28(19), 6938. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/28/19/6938

(9) Olsen, H., Grimmer, S., Aaby, K., Saha, S., & Borge, G. I. A. (2012). Antiproliferative Effects of Fresh and Thermal Processed Green and Red Cultivars of Curly Kale (Brassica oleracea L. convar. acephala var. sabellica). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 60(30), 7375-7383. doi:10.1021/jf300875f

(10) Medjakovic, S., Hobiger, S., Ardjomand-Woelkart, K., Bucar, F., & Jungbauer, A. (2016). Pumpkin seed extract: Cell growth inhibition of hyperplastic and cancer cells, independent of steroid hormone receptors. Fitoterapia, 110, 150-156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2016.03.010

(11) Rathinavelu, A., Levy, A., Dhandayuthapani, S., Murugan, R., Jornadal, J., Quinonez, Y., Gossell-Williams, M. (2013). CYTOTOXIC EFFECT OF PUMPKIN (CURCURBITA PEPO) SEED EXTRACTS IN LNCAP PROSTATE CANCER CELLS IS MEDIATED THROUGH APOPTOSIS. Current Topics in Nutraceutical Research, 11, 137-144.

(12) El-Keiy, M. , Radwan, A. and Mohamed, T. (2019) Cytotoxic Effect of Soy Bean Saponin against Colon Cancer. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines, 7, 70-86. doi: 10.4236/jbm.2019.77006

(13) Wei, Y., Lv, J., Guo, Y., Bian, Z., Gao, M., Du, H., Yang, L., Chen, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, T., Chen, J., Chen, Z., Yu, C., Huo, D., Li, L., & China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group (2020). Soy intake and breast cancer risk: a prospective study of 300,000 Chinese women and a dose-response meta-analysis. European journal of epidemiology, 35(6), 567–578. https://

(14) Suni, E., & Dimitriu, A. (2024). Anxiety and Sleep. Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/mental-health/anxiety-and-sleep

(15) Li, L., Zhang, Q., Zhu, L., Zeng, G., Huang, H., Zhuge, J., Kuang, X., Yang, S., Yang, D., Chen, Z., Gan, Y., Lu, Z., & Wu, C. (2022). Daytime naps and depression risk: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9798209/

(16) Wofford, N., Ceballos, N., Elkins, G., & Westerberg, C. E. (2022). A brief nap during an acute stressor improves negative affect. Journal of Sleep Research. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9786543/

(17) Luo, Z., Inoué, S. (2001). A short daytime nap modulates levels of emotions objectively evaluated by the emotion spectrum analysis method. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2000.00660.x

(18) Tanaka, H., & Shirakawa, S. (2004). Sleep health, lifestyle and mental health in the Japanese elderly: ensuring sleep to promote a healthy brain and mind. Journal of Psychosomatic Research.