Chris Veitch

PhD Physiology, BBiomedSc (Hons)

Jump to:

We know that sleep results in reduced:

- heart rate

- blood pressure

- slowing of brain activity

and that a short power nap can improve our mood and reduce tiredness.

But are power naps able to have a measurable impact on the body, such as improving our markers for cardiovascular health?

Biology of naps

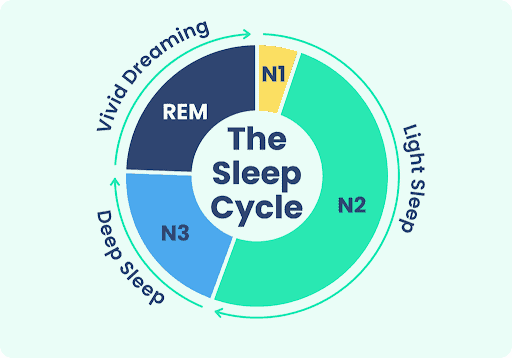

To understand naps, we first need to understand the biology of sleep. Sleep is broken into four stages, N1, N2, N3 and REM sleep, with light sleep comprising the first two stages.

RELATED — Different types of sleep: which one do we need the most?

Sleep stages typically advance sequentially, moving from N1 to N2 to N3 to REM. The first two stages last for a short time period, with N1 sleep lasting anywhere from 1-7 minutes and N2 sleep lasting between 10-25 minutes.[1]

Following light sleep, the body moves into N3 sleep, which is classified as deep sleep. During deep sleep, the body relaxes and it becomes harder to wake up from this stage. Being woken at this point by an alarm or other external stimulus leads to greater sleep inertia (grogginess following wakeup) compared to waking up during light sleep.

Due to the timing of sleep stages, this is why power naps are recommended to be around 10-20 minutes, and no longer than 40 minutes.

Power naps should be shorter than 30 minutes

Naps lasting >40 minutes are much more likely to result in entering into deep sleep, resulting in sleep inertia which can last for 30-60 minutes, and potentially longer.[2]

Sleep inertia presents itself as disorientation, poor motor and cognitive skills and decreased mood.

Heart-rate variability (HRV)

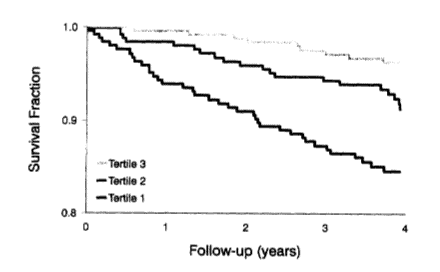

Heart-rate variability (HRV) has been identified in the scientific literature as a protective factor against development of cardiovascular disease. With decreased HRV being shown to increase risk of both cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.[3,4]

The mechanism behind this is thought to involve an imbalance between the two major branches of the nervous system

- parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest)

- sympathetic nervous system (fight and flight)

Nervous system imbalance is associated with negative health in multiple body systems.

HRV changes during sleep, resulting in a shift towards the parasympathetic nervous system. This nervous system branch shifts the body into a restful state, as our body relaxes into sleep.

This shift protects the body by decreasing inflammation, supporting immune function and improving glucose tolerance.[3]

Heart Rate (HR)

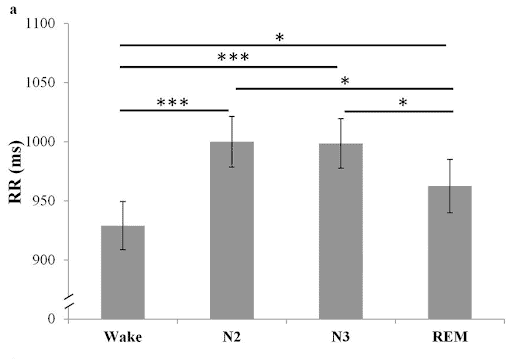

Interestingly, a 2015 study has shown that these changes in HRV and overall HR occur in daytime naps in a similar fashion to night-time sleep.

Healthy young adults took an 80–120-minute nap at 1:30pm. Significant changes in the HRV were recorded in participants throughout the nap, which was noted as being similar to the changes seen during night-time sleep.[5]

A significant increase in RR interval is shown below, which represents the time between two heartbeats, signifying a decrease in heart rate with sleep onset during the daytime nap.

Significant changes in heart function were seen in N2 sleep, which as discussed above is often achieved after only 10 minutes of sleep. This suggests that even a short 20 minute power nap may have positive effects on heart health.

A 10 minute power nap can have a positive effect on our heart rate

Another study has shown that having a daytime nap may even be able to reduce the maximum heart rate seen during a game of basketball, following a 40 minute nap opportunity compared to those who did not nap before playing.[6]

Along with this, researchers observed greater shooting performance in players who napped compared to those who did not, suggesting that both sport performance and physiological responses to exercise may be improved following a daytime nap.

Blood Pressure (BP)

Blood pressure naturally dips during the night as you fall asleep, as the parasympathetic nervous system calms the body down from daytime activities.

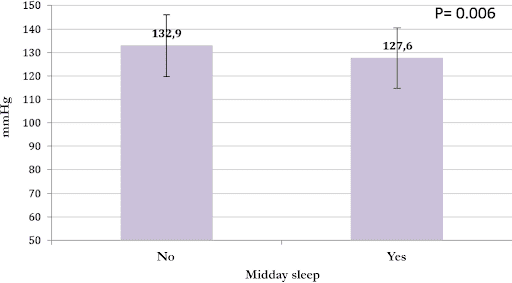

A 2020 study has shown that a midday nap may even help control blood pressure in people suffering from hypertension to an extent similar to other lifestyle changes such as reducing salt intake.[7]

Reducing either salt intake or weight loss is known to reduce blood pressure (BP) by around 3-5 mmHg, and this study showed average systolic BP recorded over 24-hours was reduced by 3 mmHg following a nap.

There are also some studies that purport that a daytime nap increases the risk of developing high blood pressure. UK researchers examined hypertension risk amongst study participants who never napped or usually napped, and found that those who usually napped had a significantly greater risk of hypertension than those who never-napped.[8]

However, this study did not account for conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea affecting this association, which can increase the risk of hypertension and also increase daytime sleepiness.

These two variables by themselves may make someone more likely to have a daytime nap.

Heart Disease Risk

Oftentimes researchers have highlighted the negative effects of daytime napping, with articles suggesting that long daytime naps actually have negative impacts on heart health.

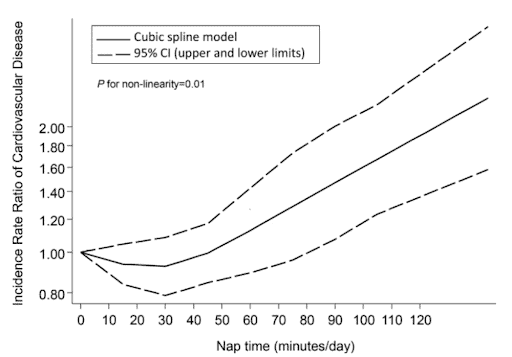

A 2015 meta-analysis of 11 studies showed an interesting relationship between nap length and the risk for developing cardiovascular disease.

Participants who self-reported a nap longer than 60 minutes/day were seen to have a significantly increased risk of developing heart disease compared to those who didn’t nap.[9]

On the other hand, participants who napped for less than 60 minutes per day had no significantly increased risk of developing heart disease compared to non-nappers.[9]

As shown below there may even be a slight protective effect of short daytime naps, with a reduced risk of heart disease seen in naps lasting <45 minutes.

Naps can reduce the risk of heart disease

This increased risk of heart disease has been seen in other studies, with participants who napped longer than 45 minutes per nap in a 2021 study showing a 1.73x higher risk of developing heart failure than those who napped less than 45 minutes per nap.[10]

The effects of underlying conditions do need to be considered when examining the above studies.

Untreated obstructive sleep apnea or other medical conditions can often cause daytime fatigue, leading to an increased chance that someone will require a daytime nap, which could be influencing the increased risk of heart disease associated with longer naps seen in the above studies.

Related Questions

1. What is the optimal time of the day to have a power nap?

Power naps should ideally happen between 1pm and 4pm.

This is the time of day when our body experiences the most sleepiness prior to night-time, known as the “post-lunch dip”.[11]

2. What is the latest time in the day I can have a power nap without impacting the quality of my night sleep?

A 20-minute power nap starting around 3:30pm would be best, considering that naps after this time can negatively impact night-time sleep.[11]

3. Can power naps increase the rate of healing?

Most healing processes associated with sleep occur during deep sleep.

If you want to help your body heal, make sure you’re getting a 7+ hours of sleep at night.[12]

Chris is currently working as a clinical physiologist, specialising in sleep medicine. He is also currently studying towards his Postgraduate Diploma in Medical Technology endorsed in sleep medicine…

If you would like to learn more about Chris, see Expert: Chris Veitch.

References

(1) Suni, E., & Singh, A. (2023). Stages of Sleep: What Happens in a Sleep Cycle. Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/stages-of-sleep

(2) National Institute for Occupational and Safety Health (NIOSH). (2020). NIOSH Training for Nurses on Shift Work and Long Work Hours. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/work-hour-training-for-nurses/default.html

(3) Thayer, J. F., Yamamoto, S. S., & Brosschot, J. F. (2010) The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. International Journal of Cardiology.

(4) Tsuji, H., Venditti, F. J. Jr., Manders, E. S., Evans, J, C., Larson, M. G., Feldman, C, L., & Levy, D. (1994) Reduced heart rate variability and mortality risk in an elderly cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation.

(5) Cellini, N., Whitehurst, L. N., McDevitt, E. A., & Mednick, S. C. (2015). Heart rate variability during daytime naps in healthy adults: autonomic profile and short-term reliability. Psychophysiology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4801685/

(6) Souabni, M., Hammouda, O., Souabni, M, J., Romdhani, M., & Driss, T. (2022). 40-min nap opportunity attenuates heart rate and perceived exertion and improves physical specific abilities in elite basketball players. Research in Sports Medicine.

(7) Kallistratos, M. S., Poulimenos, L. E., Tsinivizov, P., Varvarousis, D., Kouremenos, N., Pittaras, A., Triantafyllis, A. S., & Manolis, A. J. (2020). The effect of Mid-Day Sleep on blood pressure levels in patients with arterial hypertension. European Journal of Internal Medicine.

(8) Yang, M-J., Zhang, Z., Wang, Y-J., Li, J-C., Guo, Q-L., Chen, X., & Wang, E. (2022). Association of Nap Frequency With Hypertension or Ischemic Stroke Supported by Prospective Cohort Data and Mendelian Randomization in Predominantly Middle-Aged European Subjects. Hypertension. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19120#abstract

(9) Yamada, T., Hara, K., Shojima, N., Yamauchi, T., & Kadowaki, T. (2015) Daytime Napping and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality: A Prospective Study and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Sleep. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4667384/

(10) Li, P., Gaba, A., Wong, P. M., Cui, L., Yu, L., Bennett, D. A., Buchman, A. S., Gao, L., & Hu, K. (2021). Objective Assessment of Daytime Napping and Incident Heart Failure in 1140 Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8477879/.

(11) Lastella, M., Halson, S. L., Vitale, J. A., Memon, A. R., & Vincent, G. E. (2021). To Nap or Not to Nap? A Systematic Review Evaluating Napping Behavior in Athletes and the Impact on Various Measures of Athletic Performance. Nature and Science of Sleep. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8238550/

(12) Newsom, R., & Singh, A. (2023) Slow-Wave Sleep. Sleep Foundation. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/stages-of-sleep/slow-wave-sleep