Hannah King

BSc (Human Nutrition)

Jump to:

- What is Selenium?

- Selenium deficiency

- Different types of Selenium

- Health Benefits

- Health Claims

- Best sources of Selenium

- Daily requirements and intake

- How to take Selenium

- Signs and symptoms of deficiency

- Risks and side effects

- Interactions - herbs and supplements

- Interactions - medication

- Summary

- Related Questions

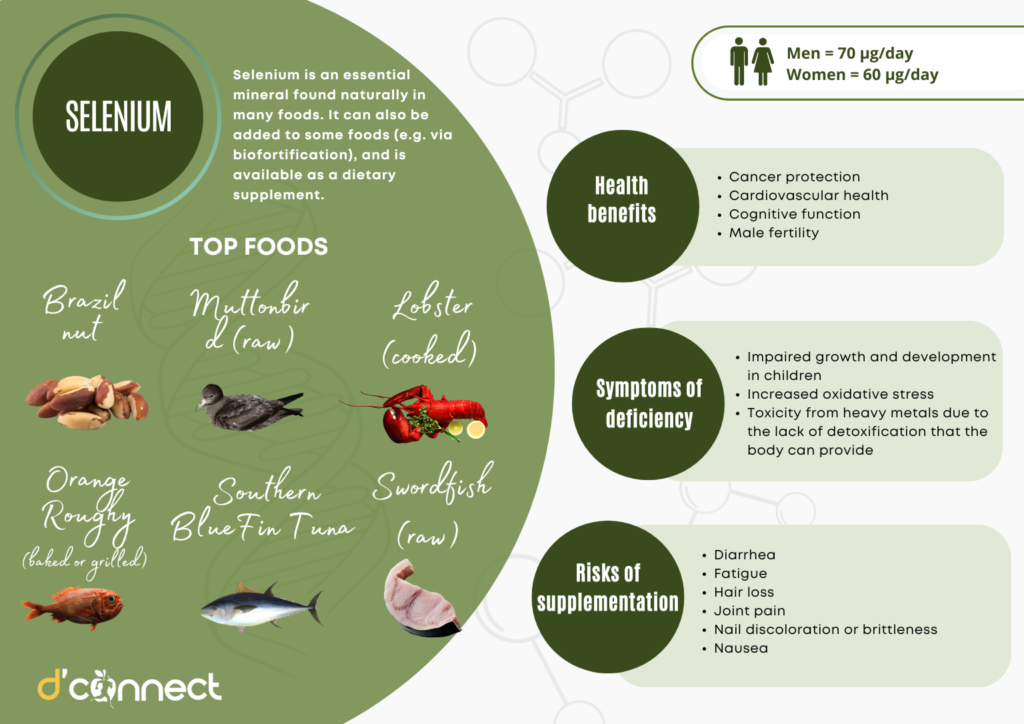

Research done on selenium has concluded that it is an essential mineral. Apart from the importance it has in thyroid and immune health, additional studies suggest that selenium might also assist with

- cancer protection

- cardiovascular health

- cognitive function

- male fertility

The last point might be quite important for men, since rates of male fertility and testosterone levels have been steadily decreasing the last 20 years.

What is Selenium?

Selenium is an essential mineral found naturally in many foods. It can also be added to some foods (e.g. via biofortification), and is available as a dietary supplement.

It plays a vital role in protecting cells from oxidative damage through its involvement in the glutathione peroxidase enzyme system. In foods, selenium is mostly present as the amino acids selenomethionine and selenocysteine.

Additionally, selenium is a key component of 25 selenoproteins. These selenoproteins are crucial for thyroid hormone metabolism, DNA synthesis, reproduction, and immune defence.[1,2]

History behind Selenium

Since its discovery in 1817, knowledge of selenium and its significance in health has evolved. It was previously considered a carcinogen, but is now recognised as a crucial nutrient.

First documented in China, selenium deficiency was associated with Keshan disease (a type of heart disease).

After supplementing individuals in areas with Keshan disease, incidence significantly dropped, providing evidence of selenium’s role in preventing the disease.[3]

Selenium deficiency

Selenium deficiency typically arises from insufficient dietary intake due to soil depletion in specific regions; one of these regions includes New Zealand, hence our history of inadequate selenium intakes.

However, selenium status has improved in recent years. This is due to the introduction of selenium-rich wheat and cereals from Australia and the use of selenium-fortified animal feeds.

According to the 2009 New Zealand Total Diet Survey, the average selenium intake for males over 25 years was 78 µg/day, exceeding the estimated average requirement. Although, regional soil variability and reliance on imported foods means that we still need to be wary about selenium intake.

A common theme with selenium deficiency is a concurrent vitamin E deficiency. This is most likely due to their closely related biological roles, as they both function as essential antioxidants, protecting cells from oxidative damage.

Different types of Selenium

Selenium exists in both inorganic and organic forms, each playing important roles in biological systems.

Inorganic selenium naturally exists in four oxidation states, which are:

- selenate

- selenite

- elemental selenium

- selenide

Biological systems then convert these forms of selenium into bioavailable organic forms, predominantly selenocysteine and selenomethionine.

Selenomethionine is added to proteins by replacing methionine, while selenocysteine is deliberately built into certain selenoproteins through a genetic mechanism that uses the UGA codon.

Selenocysteine is often found at the active sites of enzymes. Here they play a crucial role in enzyme function, hence selenium’s importance for health and physiological processes.[5]

The different types of selenium are found in various foods. Selenomethionine (the most common in food sources) is found in:

- grains

- nuts (especially Brazil nuts)

- yeast

- meat

- dairy

Then, selenocysteine is found in some animal products and selenite is often seen in supplements.

Another form of selenium called se-methylselenocysteine is specifically found in garlic and onions.[6]

RELATED — Garlic (Allium sativum)

Health benefits of Selenium

Antioxidant properties

Selenium plays a crucial role in the body’s antioxidant defense system, because of its incorporation into selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase (SeGPx). SeGPx is an enzyme that helps break down harmful peroxides.[7]

Research has shown that adequate selenium intake is necessary to optimise SeGPx activity and reduce oxidative stress.

For instance, one study that looked at morbidly obese women consuming selenium-rich Brazil nuts for eight weeks found that selenium status significantly increased, and as a result so did SeGPx activity.

Plasma selenium levels rose by 72.6–85.6 μg/L, and erythrocyte selenium levels increased by 140.0–160.5 μg/L in their participants. As a result, erythrocyte GPx activity rose by 13.8–18.9 U/g Hb, supporting antioxidant defense in the body.[8]

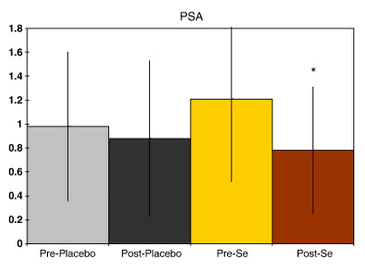

Additionally, a study involving middle-aged men demonstrated that selenium supplementation increased SeGPx activity and lowered prostate-specific antigen levels in 28/30 of their subjects. This finding highlighted a potential role that selenium has in reducing prostate cancer risk.[9]

Overall findings like these show the importance of maintaining sufficient selenium levels for health and its potential role in combating oxidative stress-related conditions.

Before supplementation, the mean PSA concentration was 1.2 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL), which decreased to 0.8 ng/mL following selenium intake.

Thyroid health and hormone metabolism

The thyroid gland produces several selenoproteins, and low selenium levels can increase the risk of thyroid issues. While selenium supplementation may not change thyroid hormone levels in healthy individuals, it could help patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, particularly those who are selenium-deficient.[10]

Low selenium levels can increase the risk of thyroid issues

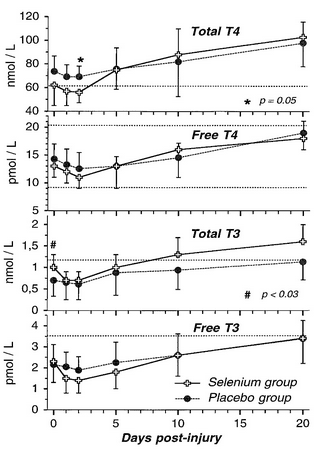

One study explored whether taking selenium supplements early could help prevent a drop in T3 hormone levels after trauma. Compared to placebo, they found supplementation significantly influenced Total T3 recovery and improved the T3/T4 ratio, which is a crucial metabolic pathway of thyroid hormones.

For instance on day 10, the T3/T4 ratio ranges in the selenium group was 11.5 – 22.5, while the placebo group had a lower ratio range of 6.6-16.3.[11]

Another insightful study investigated the effects of selenium supplementation on patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT).

In patients who had low baseline selenium levels and was in the selenium supplementation group, there was a decrease in

- TPOAb (Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies) by −37.1 IU/ml

- TGAb (Thyroglobulin Antibodies) by −43.3 IU/ml

while the control group showed increases.

Supplementation also appeared to decrease TSH (Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone) in patients with subclinical HT (2.5 mIU/L reduction), compared to the control group. All of which indicate improved thyroid function.[12]

Immune system support

Selenium deficiency can compromise immunity, increasing susceptibility to infections and possibly cancers. It is linked to higher levels of inflammatory cytokines, chronic inflammatory diseases, and inflammation-associated cancers.

But, models and human studies have demonstrated that adequate dietary selenium and its incorporation into selenoproteins are important for immune function.

Selenium supplementation can even boost the immune system by increasing the activity of T cells, NK cells, and other innate immune functions, especially when it raises selenium levels from deficient to adequate.[13]

Selenium deficiency can compromise immunity

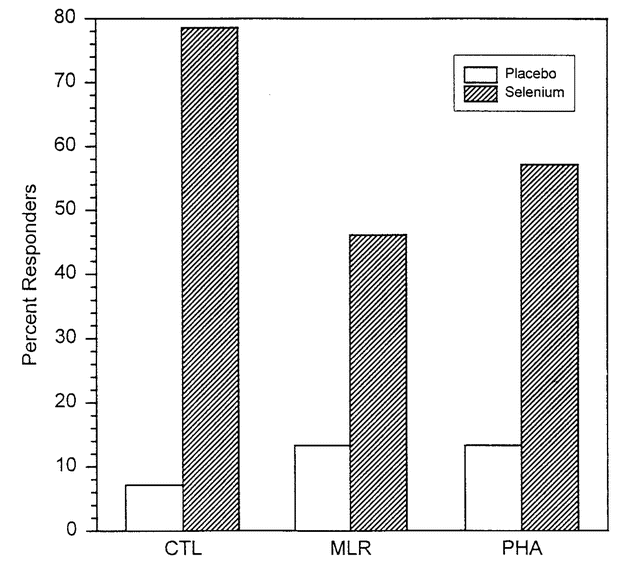

Sparked by previous research that had shown that selenium boosts immune responses, one study looked at selenium and immune function in squamous cell carcinoma patients.

They found that participants with selenium supplementation had improved immune responses, enhancing the ability to respond to stimuli and destroy tumour cells.

Responses were compared to baseline levels, with a positive response defined as a significant increase (three times the standard variation). Results show the percentage of patients in each group who had an enhanced response.

This suggests that selenium supplementation during therapy could potentially reduce morbidity associated with infections and improve tumour control.[14]

Health claims that still need more evidence and research

As outlined above there are several health benefits that selenium can offer. There are also claims around

- cancer protection

- cardiovascular health

- cognitive function

- male fertility

that have been explored but need to be considered with caution.

Cancer protection

Health claims surrounding selenium and cancer can be complex, with mixed results amongst the literature. In observational studies, higher selenium exposure has been linked to a reduced risk of cancer.

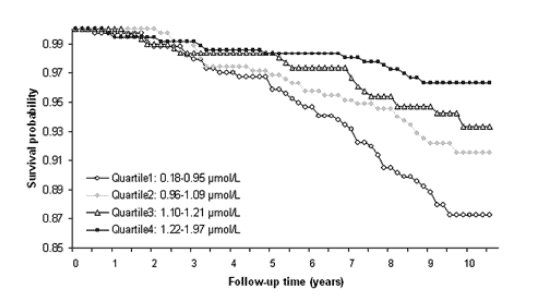

The EVA (Etude du Vieillissement Artériel) study, a 9-year longitudinal study, explored the relationship between plasma selenium levels and mortality in an elderly population.

The results showed that individuals with higher baseline plasma selenium levels had lower mortality rates.[15]

The lowest quartile of plasma selenium concentrations had the poorest survival probability and the highest quartile had the greatest survival probability.

However, many of these studies have looked at men, and evidence for women is less clear. Additionally, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown less promising results.

Studies like the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Trial (NPCT) and the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Trial (SELECT) both suggested that selenium supplements may not prevent cancer and could even pose risks, particularly for individuals with high baseline selenium levels.[16,17]

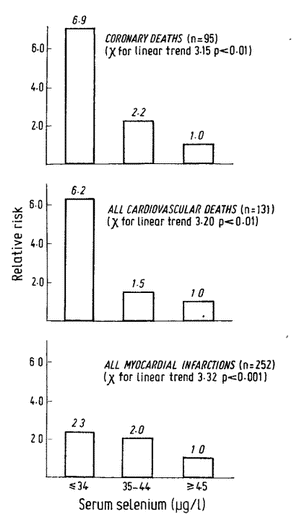

Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

There is evidence for and against the role of selenium in CVD outcomes.

A case-control study in Finland found that lower serum selenium levels were associated with a higher risk of mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD) and myocardial infarction.

In fact, the participants with selenium levels below 45 μg/L had nearly three times the risk of CHD death.[18]

Observational studies like the one above suggest there could be a relationship between selenium levels and coronary heart disease. However, RCTs have yet to confirm this. Though, the ongoing SELECT study will hopefully give us more insight.

Until then, selenium supplementation for CVD prevention is not recommended due to uncertain benefits and toxicity risks.[19]

Cognitive function

Selenium is important for brain function, and as we know helps protect against oxidative stress and inflammation. Low levels have been observed in Alzheimer’s Disease patients, so it could be that supplementation may improve selenium levels, and thus antioxidant activity, and cognitive function.

Some studies have even suggested that there have been mild cognitive improvements with selenium supplementation, particularly in memory and executive function.[20]

Selenium supplementation might assist with brain health

A 12-week randomised control trial found that selenium plus probiotics

- improved cognitive function

- reduced oxidative stress

- enhanced metabolic health in Alzheimer’s patients

Specifically they found on the MMSE score (Mini-Mental State Examination) it improved cognitive function by an average of 1.5 points.[21]

Though it is important to note that scores that improve by greater than or equal to 3 points on an MMSE are generally required to believe the improvement was not due to measurement error. Hence further research is needed in this area.[22]

Male fertility

There remains controversy in the role selenium has in male fertility. Some research suggests that selenium could improve sperm health.

One study tested whether selenium supplements, with or without extra vitamins, could improve sperm quality in men with low motility.

Their results showed that in the selenium-only group sperm movement increased by 40%, and in the selenium + vitamins group 34%. Though sperm count was less affected.

In the end, 11% of men who took selenium were able to conceive compared to none in the placebo group, which provides some evidence to suggest supplementation could be useful. Although not all participants had this outcome and conclusions are unclear.[23]

To make things more unclear, a study found that even with increased selenium levels in blood and semen, sperm quality can remain unchanged. Therefore, the testes may regulate selenium independently of intake.[24]

Best sources of Selenium

Food item | Concentration (µg/100g) |

Brazil nut | 840 |

Muttonbird (raw) | 160 |

Lobster (cooked) | 130 |

Orange Roughy (baked/grilled) | 100 |

Southern BlueFin Tuna | 99 |

Swordfish (raw) | 97 |

Canned Tuna | 90 |

Mackerel Fish | 87 |

Chicken liver (pan fried) | 81 |

Sunflower seeds | 78 |

Mussel (boiled) | 76 |

Canned Shrimp | 75 |

Egg yolk (raw) | 56 |

Lentil (raw) | 55 |

Nutri Grain Cereal | 22 |

As we can see from the table, good dietary sources of selenium include Brazil nuts, seafood, meat, poultry, and organ meats.[25]

But we can also find adequate amounts in cereals, grains, and dairy products. Selenium levels in plant-based foods can vary depending on soil conditions, meaning geographic location is very influential.

Interestingly though, in animal products selenium content remains stable due to homeostatic mechanisms in animals, regardless of variations in soil selenium.

Daily requirements and recommended intake

Age Group | Male RDI (µg/day) | Female RDI (µg/day) |

Infants (7–12 months) | 15 | 15 |

Children (1–3 years) | 25 | 25 |

Children (4–8 years) | 30 | 30 |

Children (9–13 years) | 50 | 50 |

Adolescents (14–18 years) | 70 | 60 |

Adults (19–70+ years) | 70 | 60 |

Pregnant Women (14–50 years) | – | 65 |

Breastfeeding Women (14–50 years) | – | 75 |

Nutrient Reference Values only tell us a part of the information we need.[26]

For instance in New Zealand selenium soil concentrations are lower, therefore being wary of selenium intake in the population’s diet is important.

How to take Selenium as a supplement

The recommended daily dose for selenium supplements typically ranges from 50-200 µg, with a maximum safe intake of 400 µg per day.

However, according to the Dietary Supplements Regulations 1985, selenium supplements must be manufactured and labeled with a recommended daily dose no higher than 150 µg.

For treating deficiencies, dosage should be determined by a healthcare provider.

Selenium should also be stored at room temperature, away from heat and light.

Ultimately, the how, what, when, and why of taking selenium should be determined by a healthcare professional to avoid more harm than good.[27]

Common signs and symptoms of Selenium deficiency

Selenium deficiency can cause a variety of symptoms that we can look out for. General symptoms include

- impaired growth and development in children

- increased oxidative stress

- toxicity from heavy metals due to the lack of detoxification that the body can provide

However, there are also more organ specific signs and symptoms that we may see. Some of which are expressed as a disease, for example:

- Keshan disease characterised by heart failure, cardiac enlargement, ECG irregularities, gallop rhythm, and cardiogenic shock.

- Hypothyroidism due to impaired thyroid and symptoms such as fatigue, weight gain, and cold intolerance.

- Weakened immunity increases the risk of viral infections, worsens HIV progression, raises the chance of hepatitis B or C leading to cancer, and reduces the body’s ability to fight infections.

- Kashin-Beck disease results in bone, cartilage, and joint deformities, joint enlargement, restricted mobility, and muscle pain.

- Neurological effects such as depressed mood, increased anxiety, hostile behaviour, and neurological disorders.

- Potential infertility in males due to impaired sperm health, and for females the impact of menstrual regularity.

Selenium risk and side effects

Excessive intake of selenium can lead to toxicity. A study investigating an outbreak of selenium poisoning, found that individuals who were affected endured side effects such as

- diarrhea

- fatigue

- hair loss

- joint pain

- nail discoloration or brittleness

- nausea

Although doses were extremely high (41749 μg/d).[28]

Other research in China and Venezuela have shown that prolonged exposure can impair liver function, as shown by decreased prothrombin synthesis (blood clotting protein production) and altered liver enzyme activity.[29]

The tolerable upper intake level (UL) for selenium is 400 μg/day, but toxicity symptoms won’t normally emerge till the 750–850 μg/day range.

As discussed earlier, the Dietary Supplements Regulations 1985, ensures that selenium supplements do not exceed 150 μg per daily dose, therefore preventing any toxicity risks.

Possible interactions with herbs and supplements

Selenium can interact with various supplements in both positive and negative ways. For instance the mineral works well with

- Vitamin C (Immunity and Collagen booster)

- Vitamin E

- Ergothioneine

to support antioxidant activity.

Vitamin E helps stop harmful lipid oxidation, while selenium-dependent enzymes convert these oxidized fats into safer forms. Vitamin C restores vitamin E, and selenium helps recycle vitamin C for continued use.[30]

Herbs can also interact with selenium. Astragalus, for example, that is grown in selenium rich soil can accumulate high levels of selenium.

Therefore, if it is taken alongside selenium supplements, this may increase risk of toxicity.

Selenium can slow blood clotting

Additionally, selenium can slow blood clotting, so having it with herbs that have similar effects like ginkgo may increase risk of excessive bleeding.

RELATED — Ginkgo (Ginkgo Biloba)

With that said, it is best to check with your GP or herbalist on this.[31]

Selenium and vitamin C work synergistically

In contrast to this, selenium may interfere with the B vitamin niacin in a negative way. Niacin and simvastatin (cholesterol lowering medication) can work together to improve good cholesterol (HDL) levels.

RELATED — Vitamin B3 (Niacin)

However, when taken with selenium and other antioxidants, this effect is reduced.[32]

It is unclear whether selenium alone causes this interference, but nonetheless individuals taking niacin alongside their cholesterol-lowering medications should be cautious with selenium supplementation.

Possible interactions with medication

There are some unfavourable outcomes when combining selenium with certain medications. These are

- Blood Thinners e.g. Anticoagulants/Antiplatelets, Warfarin: Selenium may slow blood clotting, increasing the risk of bruising and bleeding when combined with these medications.

- Sedatives e.g. Barbiturates: Selenium may slow the breakdown of these medications, increasing their effects and side effects.

- Immunosuppressants: Selenium boosts immune activity, potentially reducing the effectiveness of drugs that suppress the immune system.[32]

Summary

Key Takeaway — In this illustration we have outlined the most important information that you should know about Selenium.

Related Questions

1. Is selenium supplementation necessary for everyone?

No, selenium supplementation is not necessary for everyone.

For most people adequate selenium levels can be achieved through a balanced diet. However regions with low soil selenium levels may benefit from supplementation.

2. Do vegetarians or vegans get enough selenium?

Vegans and vegetarians may have a higher risk of having inadequate selenium intake.

A study in the UK found that vegans, vegetarians and omnivores had low selenium intakes, highlighting the importance of mindfulness on these diets, particularly because they avoid selenium-rich animal foods.[33]

3. Who should not take selenium supplements?

People who should avoid selenium supplements include those with autoimmune diseases, hypothyroidism, or a history of skin cancer.

High doses are unsafe, especially for pregnant women, children, and surgical patients.[33]

References

(1) Medsafe. (2000). Selenium. Medsafe. https://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/puarticles/sel.htm

(2) Office of Dietary Supplements. (2024). Selenium Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. National Institutes of Health https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Selenium-HealthProfessional/

(3) Shreenath, A. P., Hashmi, M. F., & Dooley, J. (2023). Selenium deficiency. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482260/

(4) The University of Auckland. (n.d.). Information sheet 6: Selenium. University of Auckland. https://www.fmhs.auckland.ac.nz/assets/fmhs/sms/nutrition/pcd/docs/is6-selenium.pdf

(5) Mangiapane, E., Pessione, A., & Pessione, E. (2025). Selenium and selenoproteins: An overview on different biological functions. Current Protein & Peptide Science, 15(6), Article 10.

(6) Dobrzyńska, M., Drzymała-Czyż, S., Woźniak, D., Drzymała, S., & Przysławski, J. (2023). Natural sources of selenium as functional food products for chemoprevention. Foods, 12(6), 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12061247

(7) Gamble, S. C., Wiseman, A., & Goldfarb, P. S. (1997). Selenium-Dependent Glutathione Peroxidase and other Selenoproteins: Their Synthesis and Biochemical Roles. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 68(2), 123–134.

(8) Cominetti, C., de Bortoli, M. C., Purgatto, E., Ong, T. P., Moreno, F. S., Garrido Jr, A. B., & Cozzolino, S. M. F. (2011). Associations between glutathione peroxidase-1 Pro198Leu polymorphism, selenium status, and DNA damage levels in obese women after consumption of Brazil nuts. Nutrition, 27(9), 891-896.

(9) Zhang, W., Joseph, E., Hitchcock, C., & DiSilvestro, R. A. (2011). Selenium glycinate supplementation increases blood glutathione peroxidase activities and decreases prostate-specific antigen readings in middle-aged US men. Nutrition Research, 31(2), 165–168.

(10) Schomburg, L. (2011). Selenium, selenoproteins and the thyroid gland: interactions in health and disease. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 8(3), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2011.174

(11) Berger, M., Reymond, M., Shenkin, A., Rey, F., Wardle, C., Cayeux, C., Schindler, C., Chioléro, R., (2001). Influence of selenium supplements on the post-traumatic alterations of the thyroid axis: a placebo-controlled trial. Intensive Care Medicine 27, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001340000757

(12) Hu, Y., Feng, W., Chen, H., Shi, H., Jiang, L., Zheng, X., Liu, X., Zhang, W., Ge, Y., Liu, Y., & Cui, D. (2021). Effect of selenium on thyroid autoimmunity and regulatory T cells in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: A prospective randomized-controlled trial. Clinical and translational science, 14(4), 1390–1402.

(13) Avery, J. C., & Hoffmann, P. R. (2018). Selenium, Selenoproteins, and Immunity. Nutrients, 10(9), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091203

(14) Kiremidjian-Schumacher, L., Roy, M., Glickman, R., Schneider, K., Rothstein, S., Cooper, J., Hochster, H., Kim, M., Newman, R., (2000). Selenium and Immunocompetence in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Biological Trace Element Research, 73, 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1385/bter:73:2:97

(15) Akbaraly, N. T., Arnaud, J., Hininger-Favier, I., Gourlet, V., Roussel, A. M., & Berr, C. (2005). Selenium and mortality in the elderly: results from the EVA study. Clinical Chemistry, 51(11), 2117–2123.

(16) Vinceti, M., Filippini, T., Del Giovane, C., Dennert, G., Zwahlen, M., Brinkman, M., Zeegers, M. P., Horneber, M., D’Amico, R., & Crespi, C. M. (2018). Selenium for preventing cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 1(1), CD005195.

(17) Dennert, G., Zwahlen, M., Brinkman, M., Vinceti, M., Zeegers, M. P., & Horneber, M. (2011). Selenium for preventing cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (5), CD005195. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005195.pub2

(18) Salonen, J., Alfthan, G., Huttunen, J., Pikkarainen, J., & Puska, P. (1982). Association between cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction and serum selenium in a matched-pair longitudinal study. The Lancet, 320(8291), 175-179.

(19) Flores-Mateo, G., Navas-Acien, A., Pastor-Barriuso, R., & Guallar, E. (2006). Selenium and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 84(4), 762–773. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/84.4.762

(20) Pereira, M. E., Souza, J. V., Galiciolli, M. E. A., Sare, F., Vieira, G. S., Kruk, I. L., & Oliveira, C. S. (2022). Effects of Selenium Supplementation in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 14(15), 3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153205

(21) Tamtaji, O. R., Heidari-Soureshjani, R., Mirhosseini, N., Kouchaki, E., Bahmani, F., Aghadavod, E., … & Asemi, Z. (2019). Probiotic and selenium co-supplementation, and the effects on clinical, metabolic and genetic status in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clinical Nutrition, 38(6), 2569-2575.

(22) Feeney, J., Savva, G. M., O’Regan, C., King-Kallimanis, B., Cronin, H., & Kenny, R. A. (2016). Measurement Error, Reliability, and Minimum Detectable Change in the Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and Color Trails Test among Community Living Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD, 53(3), 1107–1114.

(23) Scott, R., MacPherson, A., Yates, R. W., Hussain, B., & Dixon, J. (1998). The effect of oral selenium supplementation on human sperm motility. British journal of urology, 82(1), 76–80.

(24) Hawkes, W. C., Alkan, Z., & Wong, K. (2009). Selenium supplementation does not affect testicular selenium status or semen quality in North American men. Journal of andrology, 30(5), 525–533. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2164/jandrol.108.006940

(25) Food Composition New Zealand. (n.d.). Selenium. Food Composition New Zealand. https://www.foodcomposition.co.nz/search/nutrient?code=SE

(26) Eatforhealth.govt.au . (2021). Selenium. https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/nutrient-reference-values/nutrients/selenium

(27) Mayo Clinic. (2025). Selenium supplement (oral route).

(28) MacFarquhar, J. K., Broussard, D. L., Melstrom, P., Hutchinson, R., Wolkin, A., Martin, C., Burk, R. F., Dunn, J. R., Green, A. L., Hammond, R., Schaffner, W., & Jones, T. F. (2010). Acute selenium toxicity associated with a dietary supplement. Archives of internal medicine, 170(3), 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.495

(29) World Health Organization. (2003). Selenium in drinking-water: background document for development of WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality (No. WHO/SDE/WSH/03.04/13). World Health Organization.

(30) Hondal, R. J. (2023). Selenium vitaminology: the connection between selenium, vitamin C, vitamin E, and ergothioneine. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 75, 102328

(31) Susan G. Komen. (2025). Selenium. https://www.komen.org/breast-cancer/survivorship/complementary-therapies/selenium/

(32) WebMD. (n.d.). Selenium: Overview, uses, side effects, precautions, interactions, dosing, and reviews. https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-1003/selenium

(33) Fallon, N., & Dillon, S. A. (2020). Low Intakes of Iodine and Selenium Amongst Vegan and Vegetarian Women Highlight a Potential Nutritional Vulnerability. Frontiers in nutrition, 7, 72. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.00072