Bernadeth Atrinindarti

MAppSc (Advanced Nutrition Practice)

Blue Zones are areas of the world where residents are of particular interest to scientists due to their extraordinary longevity and vitality.

It has been found that it is not genetics, but instead the lifestyle of Blue Zone residents that is the major influence behind their long lives and low rates of chronic disease.

In this article we take a look at the lifestyle features shared by the long-lived communities of the Blue Zones:

- Japan

- Italy

- Greece

- Costa Rica

- California

- Hong Kong

Through research and studies we can learn, which common behaviours and habits we may embrace in our own lives.

What are Blue Zones?

Blue Zones are defined as areas across the world where a disproportionately high number of people live longer than the expected average. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global average life expectancy is 73 years of age.[1]

The term ‘Blue Zones’ was coined by Dan Buettner, a National Geographic Fellow and journalist, who along with a team of researchers, conducted extensive studies to identify these unique areas.

There are five areas that were originally identified as Blue Zones by Buettner. These are:

- Okinawa, Japan

- Ikaria, Greece

- Sardinia, Italy

- Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica

- Adventist community in Loma Linda, California, USA.[2]

These regions have piqued the interest of scientists, researchers, and health enthusiasts, as they provide valuable insights into what contributes to a long and healthy life.

The ongoing research on the Blue Zones, has found many other areas that have a higher number of people who live longer, such as Hong Kong.

Okinawa, Japan

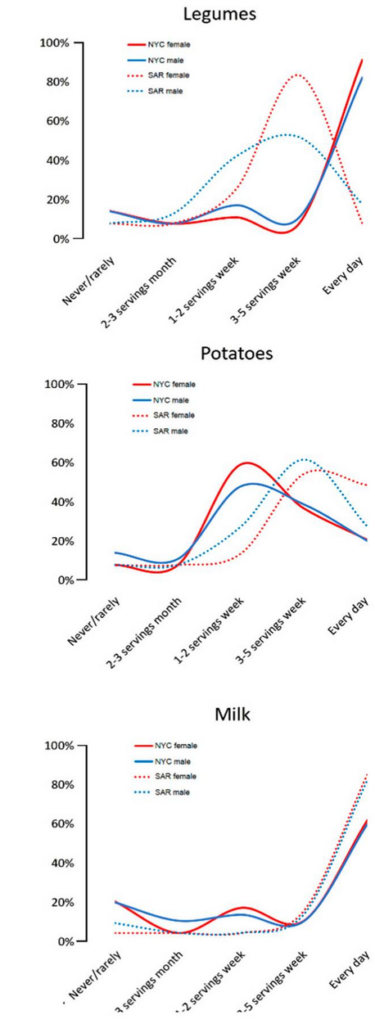

The Okinawa Prefecture, particularly the main island of Okinawa, has one of the highest life expectancies in the world.

It is an isolated island population in the southwesternmost prefecture of Japan with the lowest risk for major age-related chronic disease for most age ranges.[3]

The concept of “Ikigai”, or “reason for being” is prevalent in Okinawa. It embodies a sense of purpose and fulfilment derived from daily activities and maintaining a reason to live.

The Okinawa tradition of forming a moai provides secure social networks. These safety nets lend financial and emotional support in times of need and give their members the stress-shedding security of knowing there is always someone there for them.[4]

The Okinawan diet is deeply rooted in the region’s culture and history and has several distinctive features. A famous practice among Okinawans is “Hara Hachi Bu”, which translates to “eat until you’re 80% full”.

This practice of moderate eating helps in portion control and avoiding overeating. The diet emphasises nutrient-dense, mild caloric restriction (10-15% fewer calories than usually recommended) such as:

- legumes and vegetables,

- moderate consumption of fish, lean meat and fruits.[5]

According to a nutrition survey conducted by the Okinawa prefectural government, Okinawans eat more meat (85.5g) than the average Japanese (74.1g) and more deep-coloured vegetables (106.9g).[6]

Source: Japantimes.co.jp

Okinawans eat more meat and vegetables than the average Japanese

They consume foods that contain compounds that result in fewer cell-damaging radicals, greater insulin sensitivity and activation of the longevity gene.[5]

Sardinia, Italy

The Mediterranean island of Sardinia has been known for its high number of long-lived people over a wide period of time. The prevalence of centenarians (people who reach 100 years of age or more) was higher than in other European countries.

These numbers were particularly evident in Nuoro, the most remote and mountainous region among the four Sardinian provinces.[7]

Most men in Sardinia build their exercise into daily life through gardening, farming, and walking. They live on steeper slopes in the mountains and walk longer distances to work.[8]

Regarding diet, Sardinians prefer:

- whole, unprocessed foods, such as barley, tomatoes, olives and olive oil

- pecorino cheese made from sheep’s milk

Pecorino cheese is considered the oldest cheese in Italy, and it is used in every single meal in Sardinia.

Source: Escursi.com

A research study observed a dietary pattern evolution in the Sardinian Blue Zone and its association with health indicators.

They found that there has been an increased intake of locally produced meat (especially beef meat, goat and sheep meat) and olive oil, and it seems to be associated with improvement of health indicators.

They suggest that a supply of protein, healthy fats and antioxidants may have been crucial to maintain functional capacity.[9]

Similar to the Okinawans, the Sardinian population as a whole consumes slightly fewer calories than that of mainland Italy.[8]

Ikaria, Greece

The Greek island of Ikaria in the Aegean Sea is known for its residents’ exceptional longevity. They experience 20% less cancer, half the rate of heart disease, and almost no dementia.

Ikarians downshift with a mid-afternoon break. People who nap regularly have up to 35% lower risk of dying from heart disease.

Daily physical activity is embedded in the Ikarian way of life, primarily through gardening, walking and other forms of natural movement.

Daily physical activity appears to promote longevity

Also, the community-oriented nature of Ikarian life contributes to the residents’ sense of belonging and support. Regular social engagement and close-knit relationships are integral to their lifestyle.

Source: dianekochilas.com

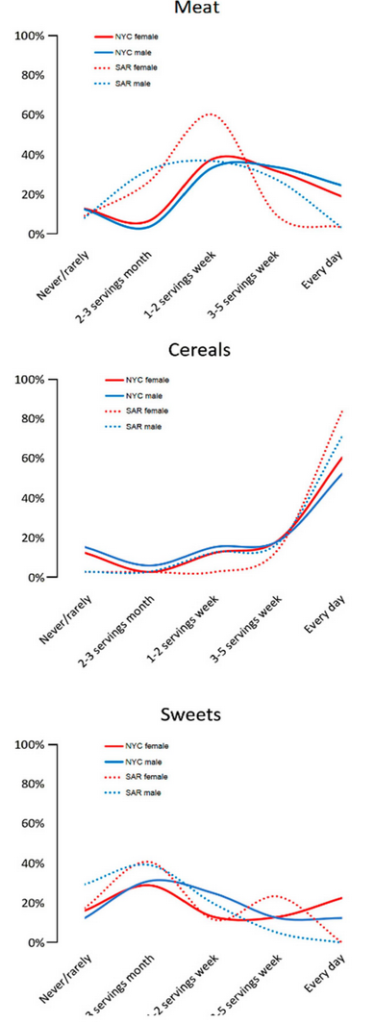

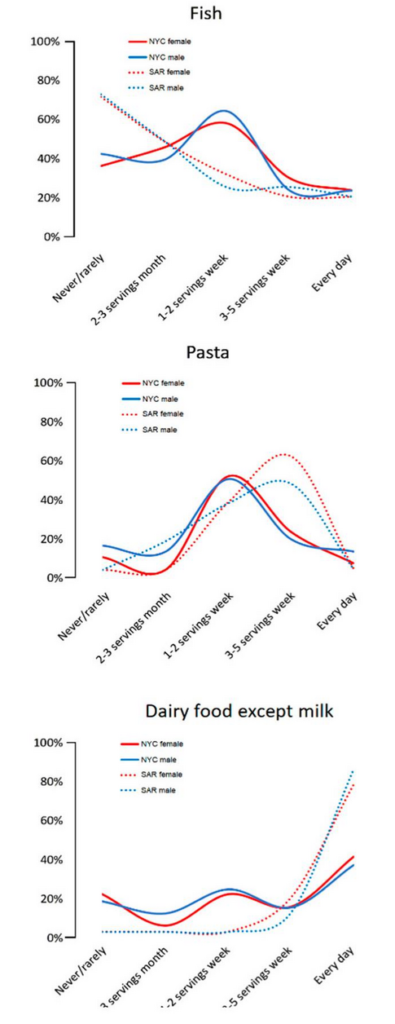

Studies showed that Ikarians display a favourable adherence to the Mediterranean diet, with:

- high consumption of olive oil, fruits, vegetables and salad, potatoes, and

- fish and red meat[10]

Moreover, Ikarians consume more than 150g of fish every week, which is positively associated with improved kidney function among elderly individuals.[11]

Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica

Located on the Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica, this region boasts low rates of heart disease and a remarkable vitality among its population. Recent research examined this high longevity in a population-based sample of elderly Costa Ricans and found that Nicoya indeed has a significantly lower death rate ratio compared to the rest of the country.[12]

Faith and family play a strong role in Nicoyan culture. Also, plan de vida, a reason to live, helps Nicoyan elders maintain a positive outlook and active lifestyle.[13]

Similar to other Blue Zones areas, Nicoyans typically engage in physical activities as part of their daily routines. They tend to do a physically demanding job such as farming and agriculture. A study found that Nicoyans maintained levels of physical activity to be consistent with the WHO recommendations for elderly people.[13]

Source: Mark Wiens - Long Life Food of Costa Rica

Regarding their isolation from large urban populations, Nicoyans are more likely to maintain customs and food traditions. They don’t consume processed foods, which are known to be widely available in the Central Valley of Costa Rica.[13]

The daily intake includes corn tortillas and black beans, which are constituents of the traditional Costa Rican diet. Meat consumption is 2-6 times per week.[13]

In addition, close-knit communities and strong family ties are integral to the Nicoyan way of life. Social interactions and support networks play a significant role in the mental and emotional health of the residents.

Loma Linda, California, USA

Loma Linda, California, is a unique Blue Zone within the United States. It is primarily inhabited by a religious community, Seventh-day Adventists.

The community is the home of over 9,000 people who tend to live up to 10 years longer than the average American.

Strong social connections among Seventh-day Adventists also play a significant role in promoting mental and emotional well-being. They also emphasise health as an essential aspect of their religious beliefs, encouraging practices that support physical, mental and spiritual health.[14]

Physical activity is a crucial part of life in Loma Linda. Residents engage in regular exercise and incorporate movement into their daily routines.[14]

The Seventh-day Adventist diet is mostly plant-based, which avoids caffeine, alcohol and other substances that they consider unclean or harmful listed in the Bible.

They predominantly focus on whole, minimally processed foods while avoiding processed and high-fat foods.

They consume a high number of legumes, whole grains, nuts, fruits, vegetables and sources of vitamin B12.[15]

Hong Kong

Hong Kong is ranked seventh worldwide with the most centenarians for every 100,000 residents according to Lottie.

The number of centenarians in Hong Kong has been increasing steadily due to improvements in healthcare, living standards, and advancement in medical science.

Hong Kong centenarians consider taking a walk as their favourite daily activity. They also manage social interaction with other people, most of them communicate with fellow elderly and initiate conversation with their families, friends and neighbours.

Their diet emphasises balance and variety, incorporating a diverse range of foods, including grains, vegetables, fruits and proteins. A study found that they had good eating habits with a regular diet without preference for any specific foods. They consume meat and vegetables and prefer them light-flavoured.[16]

They also focus on fresh, seasonal and locally sourced ingredients, minimising reliance on processed or heavily preserved foods.

In addition, they drink tea regularly, particularly green tea or other varieties with potential health benefits due to antioxidants.

Characteristics of the Blue Zones

Diet

The diets in Blue Zones are one of the key factors contributing to the exceptional health and longevity of their inhabitants.

While variations are based on cultural preferences and local resources, certain dietary patterns prevail across these regions. These are:

- Eating whole and minimally processed foods

- Portion control

Whole and minimally processed foods

Minimally processed foods are a cornerstone of the dietary habits observed in Blue Zone communities, contributing significantly to their exceptional health and longevity.

A study in the French population researched the association between the degree of food processing and cardiometabolic risk. This study showed that unprocessed/minimally processed foods were associated with lower cardiometabolic risk.[17]

Portion control

Blue Zone communities often practise mindful eating and moderation, avoiding overeating and focusing on stopping when they are 80% full.

RELATED — A Guide to Mindful Eating

This portion control prevents from eating too many calories, which can lead to weight gain and chronic disease.

Blue Zone diets avoid processed foods

A study on Okinawans observed that low-calorie intake coupled with high physical activity appears to contribute to a lifelong low BMI and reduced mortality from age-associated diseases.

Physical activity

Physical activity plays a crucial role in the lifestyle of Blue Zone communities. Blue Zone residents engage in regular physical activity through daily routines that involve natural movements.

These activities include walking, gardening, farming and household chores, which contribute to maintaining their strength, flexibility and overall fitness.

Unlike structured exercise routines common in many societies, they do not typically engage in rigorous workouts. Instead, they rely on constant movement throughout the day as part of their lifestyle.

Furthermore, many physical activities in Blue Zones are communal. For instance, walking groups or community farming activities provide opportunities for social engagement while promoting physical movement.

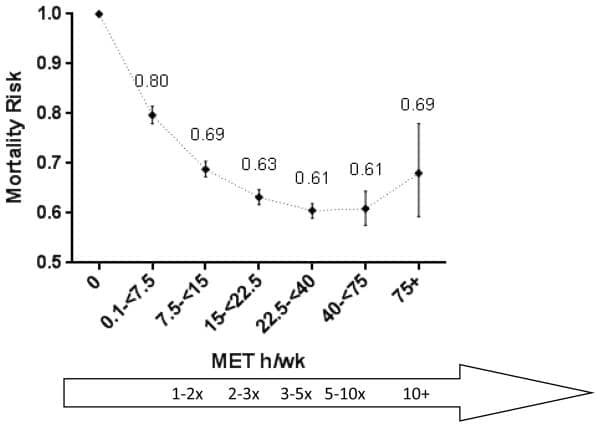

A study reported that individuals who did the recommended amount of exercise had a 20% lower risk of death who did no physical activity.[18]

Sleep

Sleep plays a vital role in overall health and well-being, and it’s an essential factor even in Blue Zone communities where people often enjoy exceptional longevity.

The Blue Zone residents typically prioritise a consistent sleep schedule. They often follow natural sleep cycles, going to bed and waking up in harmony with daylight and natural rhythms.

Some Blue Zone inhabitants have cultural practices, such as afternoon naps or periods of rest during the day, which can contribute to overall rejuvenation and well-being.

A study reported that sleep duration may be associated with the risk factors for cardiovascular disease. This study showed an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in individuals with shorter and longer duration than 8 hours of sleep.[19]

Studies showed that midday napping has no negative effect and might reduce the risk of heart disease and death.[20]

Having a life purpose

Life purpose and sense of meaning are integral components of the lifestyles observed in Blue Zones, contributing significantly to the well-being and longevity of their inhabitants.

They often maintain a strong sense of purpose throughout their lives. Whether through work, family, community engagement, or cultural practices, they find meaning in their daily activities, contributing to a positive outlook on life.

Having a sense of purpose is also associated with better mental health, lower rates of depression and increased overall happiness. This positive mindset contributes to better health outcomes and supports longevity.

A systematic study showed that individuals with a purpose in life have reduced risk for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events.[21]

A purposeful life helps mental health and happiness

Another study reported that early retirement may be a risk factor for mortality and prolonged working life may provide survival benefits among US adults.[22]

Social connection

Social connections are a fundamental aspect of life in Blue Zones playing a pivotal role in the overall health, happiness, and longevity of individuals within these communities.

Blue Zone regions often exhibit close-knit communities where individuals form deep social bonds. Residents support each other, creating a sense of belonging and mutual assistance.

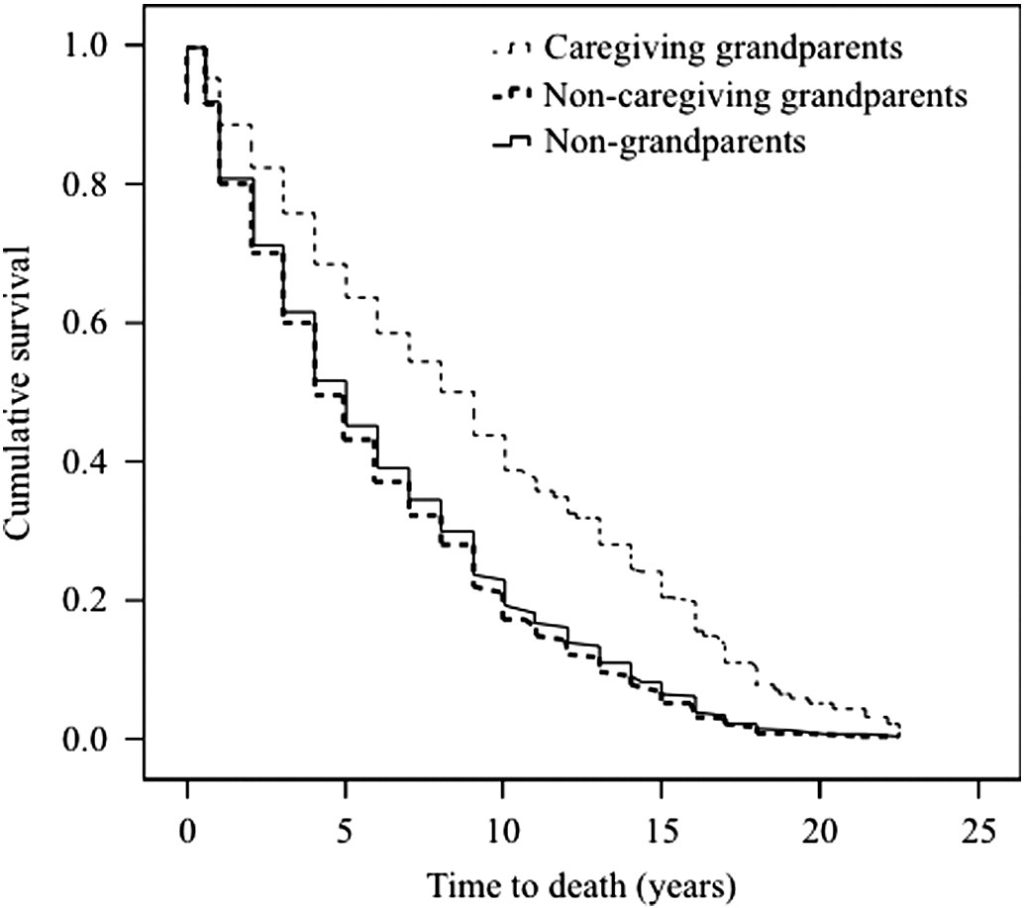

A study showed that grandparents who look after their grandchildren have a lower risk of death.[23]

Intergenerational relationships are prevalent, with respect and support flowing between different age groups. This fosters a sense of purpose, wisdom-sharing, and emotional support.

Related Questions

1. What is the life expectancy in the Blue Zones?

The life expectancy in the Blue Zones is 8-10 years longer than the average global life expectancy, which is 73 years.

2. Do inhabitants of the Blue Zones drink alcohol?

In a few regions of the Blue Zones, inhabitants drink alcohol moderately and regularly as part of their tradition.

Ikarians are known to drink 1-2 glasses of alcohol daily. Sardinians are also famous for their daily consumption of regional red wine.

3. What foods are avoided in the Blue Zones?

They mostly minimise or avoid processed foods including ready-to-eat packaged products, salty snacks, and processed meat.

Bernadeth’s passion in cooking, food and health led her to learn more about nutrition and the importance of functional foods. Throughout the years, she gained special interest in sports and performance nutrition, and the varieties of diets around the world. As a nutritionist, Bernadeth’s goal is to encourage a healthy-balanced diet and share the evidence-based nutrition knowledge in order for people to live healthier and longer lives.

Bernadeth is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect.

References

(1) World Health Organisation (WHO). Life expectancy at birth (years). 2023. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/life-expectancy-at-birth-(years)

(2) Pes, G. M., Dore, M. P., Tsofliou, F., & Poulain, M. (2022). Diet and longevity in the Blue Zones: A set-and-forget issue? Maturitas, 164, 31-37. Retrieved from doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2022.06.004

(3) D. Craig Willcox, Bradley J. Willcox, Qimei He, Nien-chiang Wang, Makoto Suzuki, They Really Are That Old: A Validation Study of Centenarian Prevalence in Okinawa, The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Volume 63, Issue 4, April 2008, Pages 338–349. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/63.4.338

(4) Mishra B. N. (2009). Secret of eternal youth; teaching from the centenarian hot spots (“blue zones”). Indian journal of community medicine : official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 34(4), 273–275. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.58380

(5) Suzuki, M., Willcox, D. C., & Willcox, B. (2015). Okinawa Centenarian Study: Investigating Healthy Aging among the World’s Longest-Lived People. In N. A. Pachana (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Geropsychology (pp. 1-5). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

(6) Shibata H, Nagai H, Haga H, Yasumura S, Suzuki T, Suyama Y. Nutrition for the Japanese Elderly. Nutrition and Health. 1992;8(2-3):165-175. doi:10.1177/026010609200800312

(7) Poulain, M., Pes, G. M., Grasland, C., Carru, C., Ferrucci, L., Baggio, G., . . . Deiana, L. (2004). Identification of a geographic area characterised by extreme longevity in the Sardinia island: the AKEA study. Experimental Gerontology, 39(9), 1423-1429. Retrieved from doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.016

(8) Pes, G. M., Tolu, F., Poulain, M., Errigo, A., Masala, S., Pietrobelli, A., Battistini, N. C., & Maioli, M. (2013). Lifestyle and nutrition related to male longevity in Sardinia: an ecological study. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases : NMCD, 23(3), 212–219.

(9) Pes, G. M., Poulain, M., Errigo, A., & Dore, M. P. (2021). Evolution of the Dietary Patterns Across Nutrition Transition in the Sardinian Longevity Blue Zone and Association with Health Indicators in the Oldest Old. Nutrients, 13(5), 1495. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051495

(10) Panagiotakos, D. B., Chrysohoou, C., Siasos, G., Zisimos, K., Skoumas, J., Pitsavos, C., & Stefanadis, C. (2011). Sociodemographic and lifestyle statistics of oldest old people (>80 years) living in Ikaria island: the Ikaria study. Cardiology research and practice, 2011, 679187. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/679187

(11) Chrysohoou, C., Pitsavos, C., Panagiotakos, D., Skoumas, J., Lazaros, G., Oikonomou, E., Stefanadis, C. (2013). Long-Term Fish Intake Preserves Kidney Function in Elderly Individuals: The Ikaria Study. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 23(4), e75-e82.

(12) Rosero-Bixby, L., Dow, W. H., & Rehkopf, D. H. (2013). The Nicoya region of Costa Rica: a high longevity island for elderly males. Vienna yearbook of population research, 11, 109–136. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2013s109

(13) Momi-Chacón, A., Capitán-Jiménez, C., & Campos, H. (2017). Dietary habits and lifestyle among long-lived residents from the Nicoya Peninsula of Costa Rica. Rev Hisp CienC salud. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7352961/

(14) Orlich, M. J., & Fraser, G. E. (2014). Vegetarian diets in the Adventist Health Study 2: a review of initial published findings 1234. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100, 353S-358S. Retrieved from doi:https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.071233

(15) WebMD Editorial Contributors. (2021). What Is the Seventh-day Adventist Diet? Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/diet/what-is-the-seventh-day-adventist-diet

(16) Li, Y., Bai, Y., Tao, Q. L., Zeng, H., Han, L. L., Luo, M. Y., Zhao, Y. (2014). Lifestyle of Chinese centenarians and their key beneficial factors in Chongqing, China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr, 23(2), 309-314. doi:10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.2.05

(17) Salomé, M., Arrazat, L., Wang, J., Dufour, A., Dubuisson, C., Volatier, J.-L., Mariotti, F. (2021). Contrary to ultra-processed foods, the consumption of unprocessed or minimally processed foods is associated with favourable patterns of protein intake, diet quality and lower cardiometabolic risk in French adults (INCA3). European Journal of Nutrition, 60(7), 4055-4067. doi:10.1007/s00394-021-02576-2

(18) Arem, H., Moore, S. C., Patel, A., Hartge, P., Berrington de Gonzalez, A., Visvanathan, K., Campbell, P. T., Freedman, M., Weiderpass, E., Adami, H. O., Linet, M. S., Lee, I. M., & Matthews, C. E. (2015). Leisure time physical activity and mortality: a detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA internal medicine, 175(6), 959–967. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0533

(19) Fengran Tao, Zhi Cao, Yunwen Jiang, Na Fan, Fusheng Xu, Hongxi Yang, Shu Li, Yuan Zhang, Xinyu Zhang, Li Sun, Yaogang Wang; (2021). Associations of sleep duration and quality with incident cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality: a prospective cohort study of 407,500 UK biobank participants. Sleep Medicine, (), –. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2021.03.015

(20) Naska, A., Oikonomou, E., Trichopoulou, A., Psaltopoulou, T., & Trichopoulos, D. (2007). Siesta in Healthy Adults and Coronary Mortality in the General Population. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167(3), 296-301. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.3.296. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/411678

(21) Cohen, R., Bavishi, C., & Rozanski, A. (2016). Purpose in Life and Its Relationship to All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events: A Meta-Analysis. Psychosomatic medicine, 78(2), 122–133.

(22) Wu, C., Odden, M. C., Fisher, G. G., & Stawski, R. S. (2016). Association of retirement age with mortality: a population-based longitudinal study among older adults in the USA. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 70(9), 917–923.

(23) Hilbrand, S., Coall, D. A., Gerstorf, D., & Hertwig, R. (2017). Caregiving within and beyond the family is associated with lower mortality for the caregiver: A prospective study. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38(3), 397-403. Retrieved from doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.11.010