Craig Ballard

(MSc (Sports & Exercise Nutrition), BSc, BTEC (Sports & Exercise Sciences), CYQ/QCF (Personal training and Instruction))

Jump to:

What if we told you that our triceps account for 60-70% of the arm’s size? Would that make you rethink your exercise choices?

A standard training split that dedicates an entire weekly gym session to arms, often known as “Arm Day”, might not be the most effective approach for achieving optimal results.

As mentioned, given that the triceps contribute to about two-thirds of our arm’s total size we decided to give this muscle group additional attention and create a 2-part article.

Understanding the Basics

While focusing solely on arms may sound appealing, it can interfere with our overall training progress, particularly with compound push and pull exercises like:

- bench presses

- dumbbell presses

- pull-ups

- lat pulldowns

These movements rely heavily on both our triceps and biceps, meaning overloading them in isolation could hinder performance in these essential lifts.

Aesthetically and functionally we want a somewhat balanced physique, so it makes sense to prioritise large muscle group (compound) exercises first before we look at isolation exercises, even if our primary goal is arm development. Why you might ask? We’ll explain later.

Let’s start with the basics before we get into the most effective strategies for targeting our triceps and maximising our growth potential.

The Triceps — function and anatomy

The triceps brachii, commonly known as the triceps, is a large muscle located on the back of the upper arm. In well developed arms, it’s often called the “horseshoe” by bodybuilders due to its distinct shape. The tricep muscle being essential for

- arm strength

- functionality

- overall aesthetics

The triceps are crucial for extending the elbow, which is essential in all pushing movements like bench presses, push-ups, and overhead presses. The triceps are the primary muscle responsible for elbow extension, otherwise known as straightening the arm.

The triceps are primary muscles responsible for elbow extension

Making up approximately two-thirds of the upper arm’s muscle mass, the triceps are crucial for achieving a fuller and more defined appearance in the arms. Their development is often the cornerstone of increasing arm size and creating a balanced, muscular physique.

Beyond aesthetics, the triceps also

- help stabilise the shoulder joint

- assist in pushing movements

- facilitate forearm extension

making them an important muscle group for both performance and overall arm functionality.

Anatomy of the Triceps

The name ‘Tri’-ceps Brachii refers to the three individual muscle heads that make up the muscle group. These are the long head, lateral head and medial head. This is important to note for exercise selection.

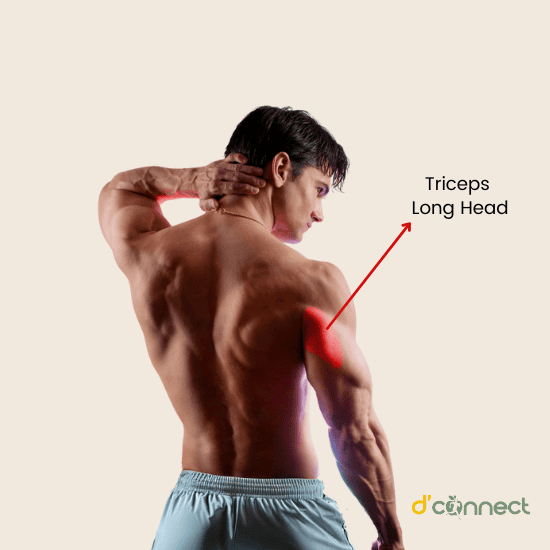

Long Head

The long head is the largest of the three heads, and it originates from the scapula (shoulder blade) and runs down the back of the arm. When we extend the arm straight out to the side, palm facing up, this head makes up most of the mass that hangs down, often referred to as “chicken wings” in less defined arms.

Due to its muscle origin, it plays a role in both elbow extension and shoulder extension (drawing your arm behind your back). Because it crosses the shoulder joint, it also assists in moving the arm overhead, which is why exercises that involve overhead motions (like overhead triceps extensions) effectively target this head over the others.

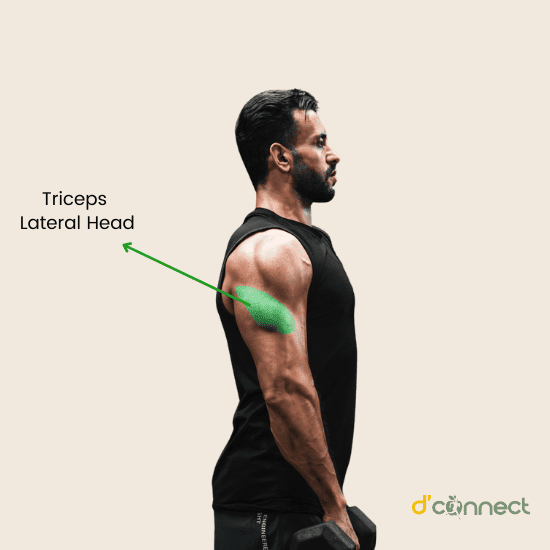

Lateral Head

The lateral head is on the outer side of the arm, originating from the upper part of the humerus (upper arm bone). This part of the triceps is what’s most visible from the front and stands out in t-shirts when the arms are well-developed.

It is primarily responsible for elbow extension and is activated most strongly during movements that involve pushing or extending the arms in front of the body, such as in close-grip bench presses or tricep cable pushdowns.

Medial Head

Situated on the inner side of the arm, the medial head also originates from the humerus but lies deeper than the other two heads. This head is primarily involved in elbow extension, especially during exercises that require significant force or when the arm is in a fully extended position. It is also engaged during heavy pushing movements.

Overall, the triceps are essential for both dynamic motion (like extension) and static positions maintaining joint integrity during various upper body exercises and activities.

Though each head is activated to some degree during pressing or pushing movements, we can put more emphasis on certain heads depending on the exercises we select. This is important for balanced development of the arm.

Key Principles of Triceps Training

The Warm-up

Traditional warm-ups, like walking on a treadmill at an incline for 10 minutes, or using a stationary bike, are often overvalued in their ability to prevent injuries, especially if they don’t specifically target the muscles or joints you plan to prioritise in your upcoming session.[4]

While dynamic and active warm-ups, including stretching, may offer some benefits in improving performance and reducing injury risk, the evidence suggests their impact is often overstated.[2]

For example, a general warm-up that raises core body temperature has minimal effect on reducing the risk of a shoulder or elbow injury before an arm-focused workout.

On the other hand, high-load dynamic warm-ups targeting the upper body, such as performing 2–3 sets of resistance exercises involving shoulder and elbow flexion and extension, have been shown to improve power and strength performance.[3]

In contrast, short-duration static stretching has no measurable effect, and methods like passive heating or cooling have been found largely ineffective, according to a systematic review examining upper body warm-ups.[3]

These targeted movements help increase elasticity, mobility, and circulation in the muscles and joints being trained, better preparing them for the demands of the workout. This not only enhances muscle function but also reduces the risk of fatigue-related injuries and supports improved overall performance.

We can optimise our warm-up by tailoring it to match our specific training session. A practical method is to perform the exercises planned for our session using lighter weights, emphasising controlled movements and a full range of motion.

These “warm-up sets” not only prime the exact muscles and joints you’ll be engaging but also help refine our technique, ensuring you’re fully prepared to meet the demands of our workout.

Progressive Overload

To make progress in the gym, incorporating the principles of progressive overload is essential. At its core, progressive overload involves consistently making our exercises more challenging over time to continue achieving results.

To keep it clear and concise there are four primary methods to apply progressive overload:

- Improving technique and form to make movements more effective at recruiting the target muscles

- Increasing load (weight) used in our exercises

- Increasing volume, which includes more repetitions, sets, or overall workload

- Reducing rest time between sets, creating greater metabolic stress in the working muscles

For example, you can track progressive overload for our triceps by logging the number of sets and reps you perform on cable pushdowns each week. Start by gradually adding 1–2 reps to each set within a target rep range (e.g., 10–15).

Once you consistently reach the upper end of that range, increase the weight. This process increases total volume and extends time under tension (TUT), driving muscle adaptation and growth by creating a greater stimulus for change.[4]

Training frequency also plays a key role, allowing you to increase training volume over a set period of time i.e., one week. Muscles typically need 48-72 hours to recover from an intense workout.[5]

Muscles need 48-72 hours to recover from an intense workout

If recovery takes longer, it may indicate that you’re doing too much volume in one session. Meaning, you are doing more work than is necessary to create a growth response, instead leading to more muscle damage. Conversely, faster recovery could mean you can handle more load or volume.[6]

Major muscle groups like our quadriceps or back musculature benefit from being trained at least twice a week for optimal hypertrophy, while smaller muscle groups, like the arms or calves, may recover more quickly and tolerate more volume/frequent sessions. However, recovery rates and training capacity vary individually based on how you respond to a given stimulus.[6]

A range of 12-20 weekly sets per muscle group is suggested as an optimal standard for muscle hypertrophy, with 5-30 repetitions per set providing an adequate stimulus, provided the intensity approaches failure (e.g., 1-3 repetitions in reserve).[8,9]

That’s not to say you have to do a different exercise for every muscle group to reach our weekly set quota. Considering that compound exercises engage multiple muscle groups, any compound pressing movement will also count as sets for the triceps.[8,9]

With that in mind you could theoretically get away with doing as little as 0-6 direct weekly sets for arm growth on top of our main exercises, depending on our training status.[10] Finally, while muscle hypertrophy (growth) is not strictly dependent on heavy loads, improvements in muscle strength are more significant when following high-load resistance training programs.[11]

Advanced training methods, such as reducing rest time between sets or increasing intensity with supersets or drop sets, can be effective, time-efficient strategies for enhancing both muscle hypertrophy and metabolic stress.[12]

There is a graded dose-response relationship where increased resistance training volume results in greater muscle hypertrophy over time. Each additional set contributes to a small but cumulative increase in muscle size.[13]

Here is a quick example for how you might program your tricep training:

Beginner

- Volume: 6–8 sets per week

- Split across 2 sessions, with 3–4 sets per session

- Focus on fundamental exercises like cable pushdowns, tricep dips (assisted if necessary), and close-grip bench presses

Intermediate

- Volume: 10–15 sets per week

- Spread over 2–3 sessions, with 4–6 sets per session

- Use a mix of compound lifts (close-grip bench press, dips) and isolation exercises (overhead tricep extensions, rope pushdowns)

Advanced

- Volume: 15–20+ sets per week

- Spread over 3–4 sessions, with 5–7 sets per session

- Incorporate advanced techniques like drop sets, supersets (e.g., close-grip bench press followed by cable pushdowns)

Equipment Options

With flashy new machines and trendy workouts flooding social media, it’s easy to get distracted. However, the fundamentals often outperform many of the newer, gimmicky options. Some equipment is simply more effective because it allows you to apply greater resistance to the target muscle while also providing better stability for the shoulder joint.

Each piece of equipment and exercise selection offers unique benefits and movement patterns, meaning there’s no definitive “right” or “wrong” choice, just alternatives to explore and incorporate into your training program.

To make it easy, you have six main options to choose from:

Bodyweight (push-ups, dips)

Advantages

- Requires no equipment and can be done anywhere

- Utilising our body as resistance

- Scalable with variations (e.g., incline push-ups for beginners, weighted dips for advanced)

- Low injury risk with proper form

Disadvantages

- Limited ability to progressively overload without adding external resistance (e.g., weighted vests/belt)

- It may be difficult to isolate specific muscles (e.g., targeting the triceps versus chest during push-ups)

Dumbbells

Advantages

- Allows a full range of motion, accommodating individual biomechanics and reducing joint stress

- Promotes bilateral balance by targeting each limb independently

- Versatile: Can be used for compound and isolation movements

Disadvantages

- Requires greater stabilisation, which may limit maximum load compared to machines or barbells

- Some exercises may be awkward or uncomfortable due to the fixed grip or hand positioning

Barbells

Advantages

- Ideal for lifting heavier loads

- Excellent for compound lifts (e.g., bench press, squats, deadlifts) that target multiple muscle groups

- Easier to progressively overload compared to other equipment

- Consistent weight distribution makes movements stable and efficient

Disadvantages

- Requires good technique and setup to avoid injury, especially under heavy loads

- Limited range of motion compared to dumbbells (e.g., during pressing or rowing movements)

- May not be ideal for individuals with joint pain or mobility issues due to fixed movement patterns

- Less effective for isolating specific muscles compared to cables or machines

Resistance Bands

Advantages

- Can be used to mimic cable machine exercises at a lower cost

- Provides variable resistance, making certain portions of the movement harder (e.g., the top of a bicep curl)

Disadvantages

- Limited maximum resistance, making them less effective for building significant strength in advanced trainees

- Resistance can be inconsistent due to band elasticity and range of motion

- Difficult to precisely track progressive overload compared to free weights

- Often less stable for compound lifts

Cable Machines

Advantages

- Provides constant tension throughout the entire range of motion

- Highly versatile for both compound and isolation exercises

- Adjustable angles and attachments allow for a wide variety of movement patterns

- Safer for beginners and effective for targeting smaller muscle groups

Disadvantages

- Limited availability

- May not be optimal due to load limitations

- Less stabilisation required compared to free weights, potentially limiting secondary muscle engagement

Resistance Machines (cable & plate loaded)

Advantages

- Beginner-friendly with controlled movement patterns that minimise injury risk

- Excellent for isolating specific muscles

- Eliminates the need for stabilisation, allowing the use of heavier loads for certain muscles

- Accessible for individuals with joint issues or mobility limitations

Disadvantages

- Fixed movement paths may not accommodate individual biomechanics, increasing discomfort for some users

- Less functional, as stabilisation and secondary muscle engagement are minimal

- Limited versatility compared to free weights or cables

For our previous Exercise Guides, see Activities and Performance section.

References

(1) Ushirooka, N., Muratomi, K., Omura, S., & Tanigawa, S. (2023). Does the addition of lower-body aerobic exercise as a warm-up improve upper-body resistance training performance more than a specific warm-up alone? Journal of Trainology, 12(2), 24–28.

(2) Fradkin, A. J., Gabbe, B. J., & Cameron, P. A. (2006). Does warming up prevent injury in sport? Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 9(3), 214–220.

(3) McCrary, J. M., Ackermann, B. J., & Halaki, M. (2015). A systematic review of the effects of upper body warm-up on performance and injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(14), 935–942. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094228

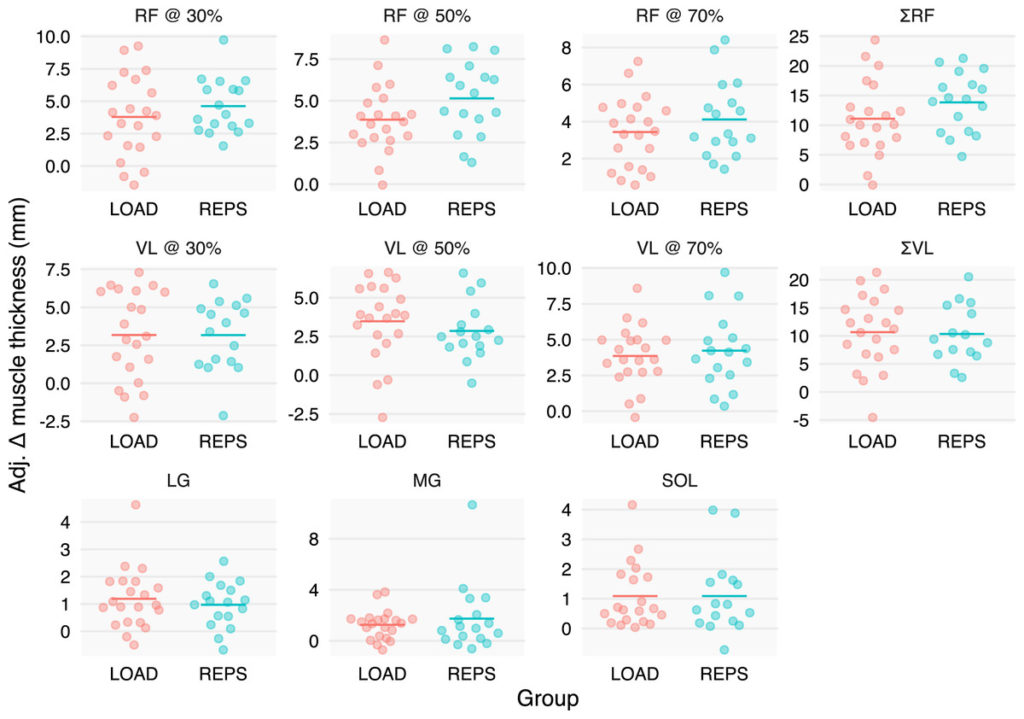

(4) Plotkin, D., Coleman, M., Van Every, D., Maldonado, J., Oberlin, D., Israetel, M., Feather, J., Alto, A., Vigotsky, A. D., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2022). Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations. PeerJ, 10, e14142. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14142

(5) Morán-Navarro, R., Pérez, C., Mora‐Rodriguez, R., Cruz-Sánchez, E., González-Badillo, J., Sánchez-Medina, L., & Pallarés, J. (2017). Time course of recovery following resistance training leading or not to failure. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 117, 2387 – 2399.

(6) Soares, S., Ferreira-Junior, J. B., Pereira, M. C., Cleto, V. A., Castanheira, R. P., Cadore, E. L., Brown, L. E., Gentil, P., Bemben, M. G., & Bottaro, M. (2015). Dissociated time course of muscle damage recovery between single- and multi-joint exercises in highly resistance-trained men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(9), 2594–2599. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000000899

(7) Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2016). Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 46(11), 1689–1697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0543-8

(8) Baz-Valle, E., Fontes-Villalba, M., & Santos-Concejero, J. (2021). Total number of sets as a training volume quantification method for muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 35(3), 870–878. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000002776

(9) Baz-Valle, E., Balsalobre-Fernández, C., Alix-Fages, C., & Santos-Concejero, J. (2022). A systematic review of the effects of different resistance training volumes on muscle hypertrophy. Journal of Human Kinetics, 81, 199–210. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2022-0017

(10) Hammert, W. B., Moreno, E. N., & Buckner, S. L. (2023). The importance of previous resistance training volume on muscle growth in trained individuals. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 46(2), 251–255.

(11) Lopez, P., Radaelli, R., Taaffe, D. R., Newton, R. U., Galvão, D. A., Trajano, G. S., Teodoro, J. L., Kraemer, W. J., Häkkinen, K., & Pinto, R. S. (2020). Resistance training load effects on muscle hypertrophy and strength gain: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53(6), 1206–1216.

(12) Krzysztofik, M., Wilk, M., Wojdała, G., & Gołaś, A. (2019). Maximizing muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review of advanced resistance training techniques and methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244897

(13) Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2016a). Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(11), 1073–1082.