Tiana Hape-Cramond

(Associate Registered Nutritionist)

Note — The article was checked and updated August 2023.

We all have a different relationship with food – it can provide us with comfort, sustenance or joy. On the other hand, for some, food can have a negative effect on their mental health.

Eating disorders are a mental health problem which can cause serious physical health issues.

Eating disorders have been present throughout history including anorexia and bulimia, and later on we have recognised new disorders such as pica, rumination disorder, purging, Prader-Willi syndrome, orthorexia and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID).

The cause of eating disorders is still unknown but thought to be influenced by many factors, which we have explained in more detail below.

To begin to understand eating disorders, we have to go back and see the origins and developments in eating disorders.

History behind Eating Disorders

Eating disorders have been around for hundreds of years dating back to roughly the 12th or 13th century. Saint Catherine of Sienna was one of the most well known women who starved herself as a religious practice. This practice comes from the belief that food was a sin and starving was a sign of their devotion to God.

From the 17th to the 19th century there were several clinical diagnoses of “wasting disease” which was given to those who showed anorexia symptoms. In 1873, Sir William Gull established the term “anorexia”. During this time period, anorexia had started to move from devotion to God to fields of medicine and psychiatry.[1]

In 1973, Hilde Bruch published a book that included a number of case studies on obesity and anorexia which increased public awareness, increased cases and the condition spread beyond the upper class.[2]

Bulimia nervosa had its first clinical paper published in 1979

The cases of anorexia and bulimia increased and peaked in the 1970’s and 1980’s. The trend of cultural pressures for thinness and increases in depression and obsessive compulsive behaviours competed for the rise of obesity in America and low fat diets became mainstream.

RELATED — What is HAES: Does it promote obesity and is it healthy?

Until this time, the two main eating disorders being discussed were anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. However, binge eating has also been around for centuries but seems to have escalated in numbers recently.

Binge eating first appeared in literature in 1959 who called it Night Eating Syndrome but later specified that binge eating can occur outside of nocturnal hours.[3]

Moving into the 90’s and 2000’s both anorexia and bulimia had a clear decrease in females ages 20 to 39 years. In 1993 the incidence rate for women aged 20 – 39 was 56.7 per 100,000 which decreased in 2000 to 28.6 per 100,000.[4]

Understanding these illnesses allows for expansion and evolution of our knowledge on the causes of these illnesses and ways we treat them.

Causes and symptoms of Eating Disorders

Symptoms of eating disorders vary between the types of eating disorders.

Common symptoms of (all) eating disorders are:

- Extreme concern about being “too fat” and thinking about food and dieting all the time

- Secret eating and purging

- Spending long periods of time in the toilet immediately after meals

- Strenuous exercise routine

- Severe weight changes

- Poor concentration and feeling unusually tired

- Obsessed with body image and the pursuit of thinness

- Sudden mood changes, depression, sadness, or anger

RELATED — Introduction to: Depression

The direct causes of eating disorders are unknown, but like other mental illnesses there can by man contributing factors such as:

Genetic and biology

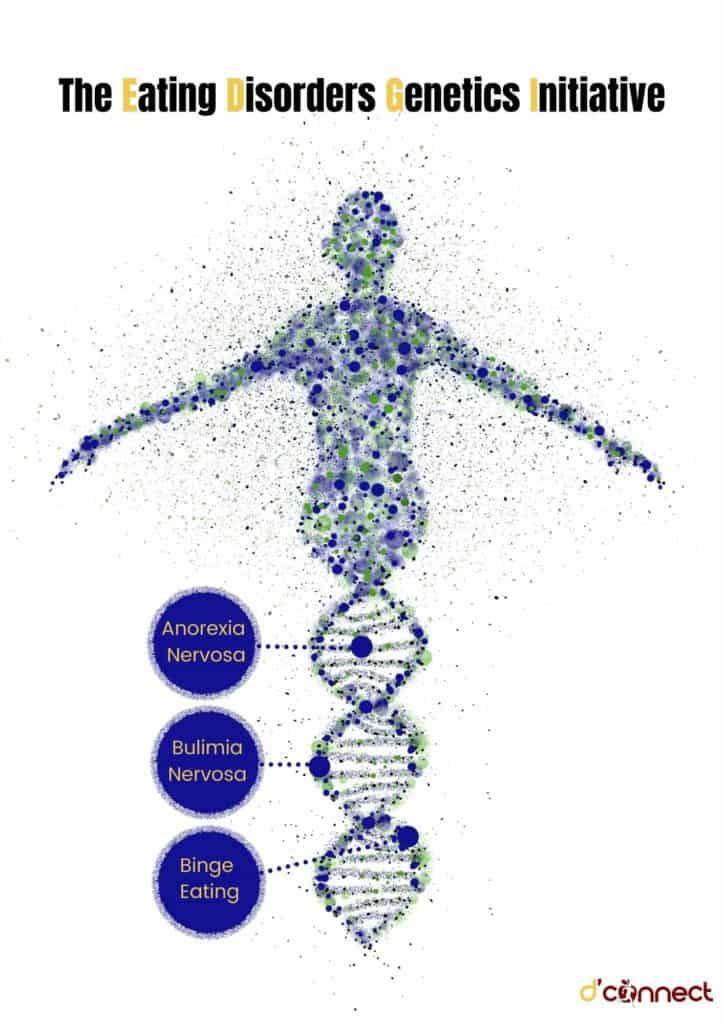

Eat Disorders Genetics Initiative is an organisation that is working towards investigating the genes that may increase the risk of developing eating disorders. Biological factors such as a chemical change in the brain may have a role in developing an eating disorder.

Psychological and emotional health

Psychological and emotional health may contribute to the development of eating disorders. Individuals may have low self-esteem, perfectionism, impulsive behaviour or troubled relationships.

Family history

People who have parents or siblings who’ve had an eating disorder are more likely to develop eating disorders.

Other mental health disorders

People with a history of anxiety disorder, depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder have a greater risk of developing disordered eating.

RELATED — Increase in Anxiety: Are we “The Anxious Generation”

Dieting or starvation

Dieting is a risk factor for developing an eating disorder as it induces restrictive eating behaviours. Starvation is a risk factor as it affects the brain and can influence mood, thinking, anxiety and a reduction in appetite.

Starvation and weight loss may influence the way the brain works in vulnerable people which can lead to restrictive eating behaviours that can make it difficult to return to normal eating habits.

Stress

Changes in stress can increase the risk of developing an eating disorder as people may crave control in their own lives which leads to restrictive eating behaviours or stress can decrease appetite which is a risk for developing disordered eating.[5]

RELATED — Understanding Stress: The Silent Killer

The Eating Disorders Genetics Initiative

Eating Disorders Genetic Initiative (EDGI) is the world’s largest investigation on the genetics involved in eating disorders. EDGI aims to build on the research of the genome-wide association study by the Eating Disorders Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium.

They identified 8 significant loci associated with anorexia nervosa and genetic correlations with both psychiatric and metabolic trains. This suggests that anorexia nervosa is a metabo-psychiatric disorder.[6]

Despite decades of work investigating the heritability, burden, mortality and morbidity that is associated with Bulimia Nervosa and binge-eating disorder there has been no genome-wide association study of those disorders.

Eating Disorders Genetics Initiative is designed to determine phenotype and genotype of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in samples taken from the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Denmark. Currently there are 14,500 individuals with eating disorders included in this study with 1500 controls over these four countries.

In the United States, Australian and New Zealand, participants will complete a comprehensive online phenotyping and submit a saliva sample for genotyping. In Denmark, individuals are identified with eating disorders using the National Patient Register, and genotyping will occur using blood spots collected at birth.[6]

The New Zealand arm of the EDGI aims to identify the genes that predispose individuals to developing anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder in order to improve treatments.

New Zealand aims to recruit more than 3,500 individuals diagnosed with an eating disorder and a control group by March 2022.

To be eligible to participate in this study, participants must be 16 years or over and diagnosed with or currently living with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervose or binge eating disorder.[7]

Types of Eating Disorders

There are different types of eating disorders and understanding each one leads to a more effective treatment and increased awareness of signs and symptoms for potential diagnosis of these eating disorders.

The most common eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder.

Anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa, more commonly referred to as anorexia, is a potentially life threatening disorder which is characterized by a low body weight, intense fear of gaining weight and a distorted perception of body shape or weight. People with anorexia have an extreme need to control their body weight and shape.[8]

Common signs of anorexia are:

- Excessively limiting calories

- Excessive exercise

- Diet aids

- Laxatives

- Vomiting after eating

The treatment of anorexia has to address all aspects of the illness including medical, nutritional, psychological and behavioural. For adolescents, family behavioural therapy is recommended as it has the highest evidence to be effective.

In adults, psychological therapy is essential with specialised therapist led treatments. There is no conclusive evidence to support which treatment is the best for each individual.[8]

Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder is similar to anorexia as both disorders have limitations on the amount or types of food that are eaten. ARFID was previously known as selective eating disorder and people with ARFID do not typically consume enough calories to grow and develop properly.

Selective eating disorder may sometimes be used interchangeably with ARFID.[9]

ARFID is different from picky eating

Picky eating is common in children and tends to not persist long term whereas ARFID exhibits the same behaviours but leads to malnutrition and weight loss with medical complications.[9]

RELATED — The Healthy Plate Model: Essentials of Healthy Eating

Signs and symptoms of ARFID include:

- Dramatic weight loss

- Gastrointestinal complaints

- Dizziness

- Dry skin

- Thinning hair

- Muscle weakness

- Impaired immune function

- Sleep problems

RELATED — Different types of sleep: which one do we need the most?

As this disorder is relatively new, there is limited scientific evidence based treatment recommendations. The goal of treatment is to increase weight and correct the nutritional deficiencies that have occurred as a result of ARFID. Treatments are individualised but can include behavioural coaching to manage meal times and introducing new foods.[10]

Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa, commonly called bulimia. Bulimia often has episodes of bingeing on food and then purgings. Many people with bulimia often experience restrictive eating during the day which often leads to more binge eating and purging.

During a binge, people often experience a loss of control and then experience shame and guilt which fuels the need to prevent themselves from gaining weight. This can include vomiting, exercise or using medications such as laxatives.[11]

Common signs of bulimia are:

- Frequent episodes of eating large amounts

- Lack of control over eating

- Fluctuations in weight

- Sore throat, tooth decay, bad breath

- Excessive exercising

- Depressed mood

- Increased social isolation

- Irregular menstrual cycles

The best treatment for bulimia is cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy is aimed at treating mental health issues. In young adults, family based treatment has been found to have better results than cognitive behavioural therapy as including the family gives the adolescent a support system to aid their changes.[11]

Binge Eating

Binge eating, sometimes referred to as compulsive eating, is an eating disorder which has recurring episodes of eating significant amounts of food. During binge eating, episodes are marked by feeling a loss of control.

RELATED — The Ultimate Guide to Intuitive Eating (with steps)

Individuals with binge eating often find themselves in a cycle of restricting food intake or dieting in order to not gain weight.[12]

Common signs of binge eating include:

- Eating unusually large portions of food

- Experiencing the compulsive urge to eat

- Experiencing eating behaviours that are out of their control

- Feeling depressed

- Frequently dieting

- Yo-yo dieting

Treatment most effective for binge eating disorder is also cognitive behaviour therapy.

RELATED — Binge Eating disorder: Is it a mental illness or an excuse to overeat?

Some medications have proven to be useful in treating binge eating disorder. Antidepressants can be used in conjunction with psychological treatment and anti-epileptic drugs have also been shown to be effective treatment.[12]

Pica

Pica is an eating disorder where individuals consume items that are not food and do not contain any significant nutritional value. This condition is common in children and is linked to some types of intellectual disabilities like autism.

It is important to understand that children under the age of 2 are not diagnosed with pica because it is common for children that young to explore by putting foreign objects into their mouths.[13]

Symptoms of pica include:

- Persistent eating of substances that aren’t food over a period of at least a month

- Nausea

- Pain in the stomach

- Constipation

- Stomach ulcers

- Intestinal blockages

- Fatigue

- Behavioral problems

- Lead poisoning or poor nutrition

As pica behaviour has similar features to bulimia and obsessive compulsive disorder, treatment includes behaviour modification and behavioural managing medications which may reduce the urges and impulses to eat nonfood items.[13]

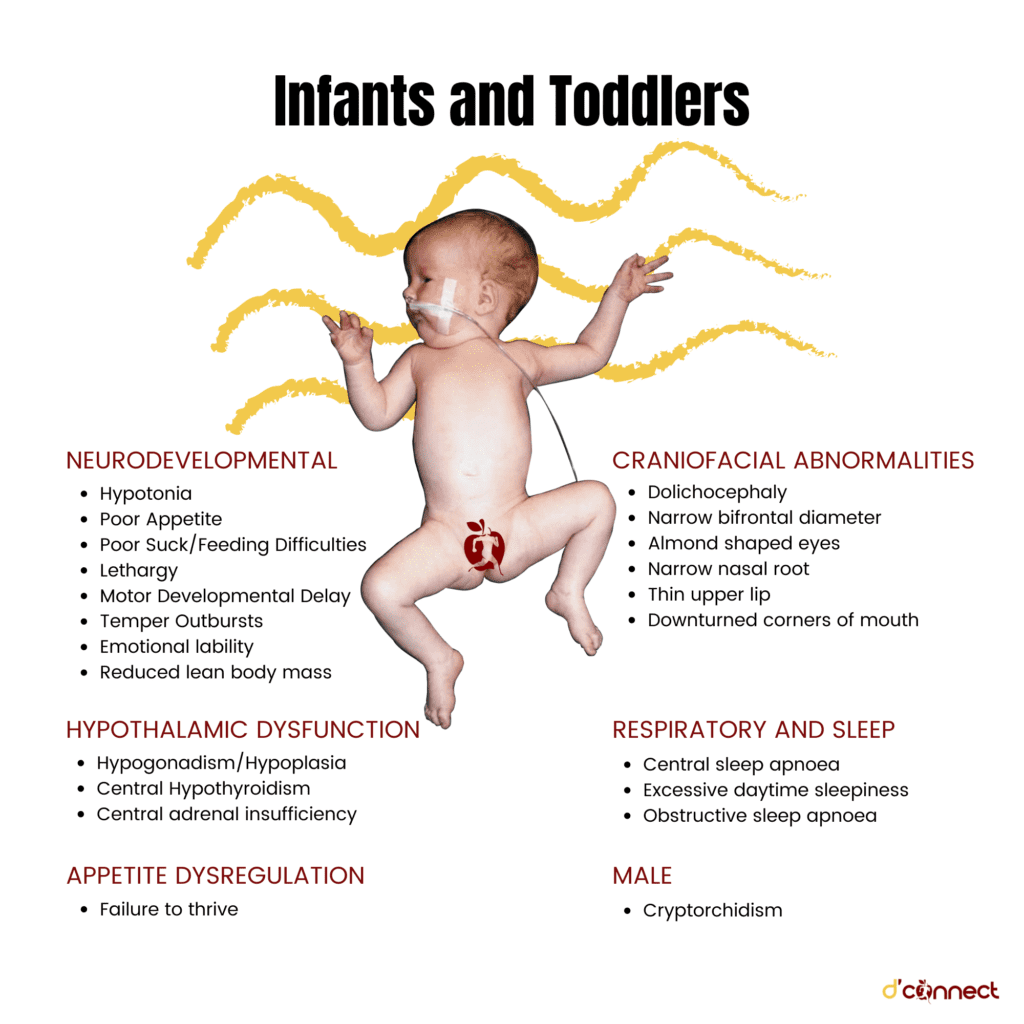

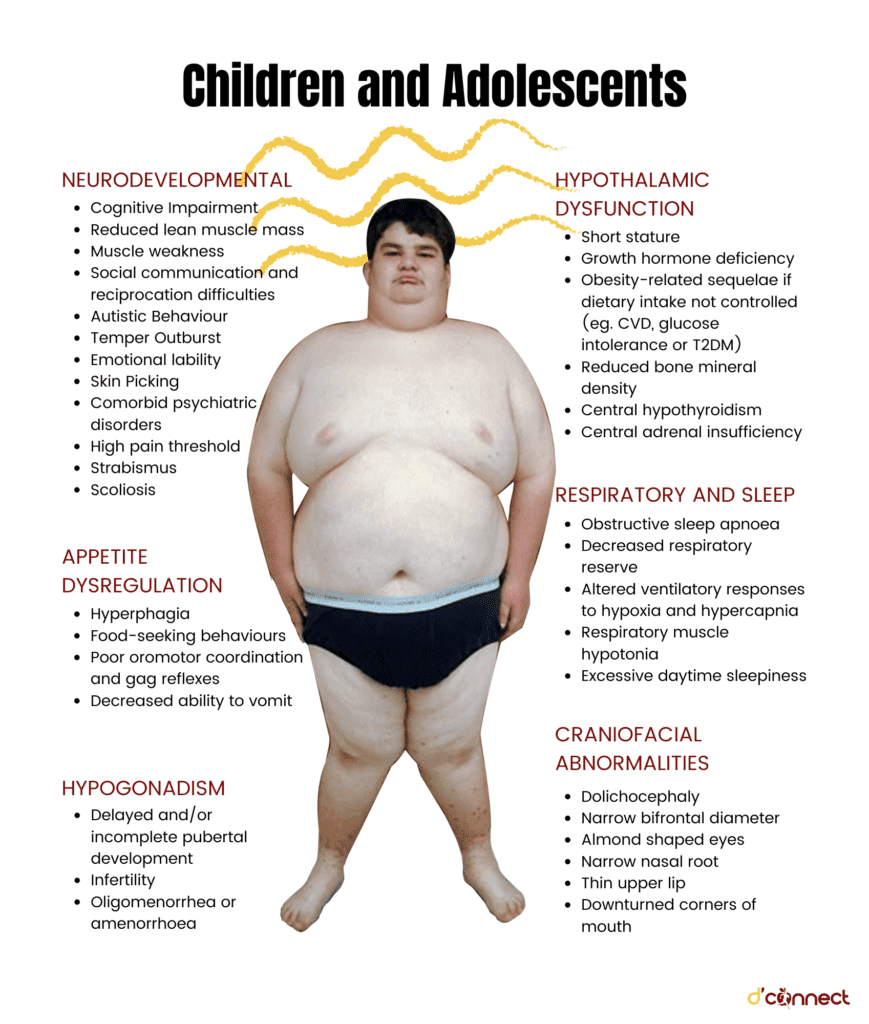

Prader-Willi syndrome

Prader-Willi syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that causes physical, mental and behavioural problems. A person with Prader-Willi syndrome has difficulty in controlling their body weight because they have a compulsion to eat as much food as possible.

Prader-Willi syndrome is the most common genetic cause of obesity in children

People with Prader-Willi syndrome have seven genes on chromosome 15 that are either deleted or inactive.[14]

Symptoms of Prader-Willi syndrome develop in two stages. The first stage is usually during the first year of life and the second stage symptoms develop between 1 and 6 years old.

Symptoms in the first year include:

- Poor muscle tone

- Special facial features

- Reduced physical development.

Symptoms that develop in the second stage are:

- Food cravings

- Gaining weight

- Limited growth and strength

- Limited cognitive development

- Delayed motor and verbal skills

- Sleep disorders

There is no cure for Prader-Willi syndrome. There are, however, therapies that work towards reducing symptoms. Therapies for this condition include nutrition counselling, speech and occupational therapy, sex hormone treatment, growth hormone treatment and specialised care and supervision.[14]

Purging

Purging is an eating disorder where individuals exhibit purging behaviour to lose weight or change their body shape. Purging behaviours can be self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives or medications, excessive exercise and fasting.

RELATED — Intermittent Fasting: The Medicine of Old

Bulimia nervosa and purging share similar purging behaviours. However, the difference is that with bulimia there is a compulsion to binge eat.

Symptoms of purging disorder are similar to those of other eating disorders and include recurring episodes of purging behaviours, emotional distress, fear of gaining weight and self esteem issues.

RELATED — A Guide to Mindful Eating

The treatment of purging disorder is personalised to the individual to make treatment more effective. Treatments can include intensive inpatient treatment, recovery programs, psychotherapy and nutrition counselling.[15]

Rumination disorder

The regular regurgitation of food is an eating disorder known as rumination disorder. This is when food is re-chewed, re-swallowed or spit out.

Rumination disorder is diagnosed when an individual has been regurgitating food for at least one month and the regurgitation is not an effect from an existing medical condition.

Symptoms of rumination disorder are:

- Effortless regurgitation

- Abdominal pain

- Bad breath

- Nausea

- Unintentional weight loss.[16]

Treatment for rumination syndrome is ruling out if there is a physical cause for this regurgitation. Next step to treating rumination syndrome may include a combination of breathing exercises and habit reversal.[17]

Orthorexia

Although orthorexia is not officially recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual the term orthorexia was coined in 1998 to mean the obsession with proper and “healthy” eating.

Being conscious and aware of eating nutritious food isn’t necessarily harmful, but individuals with orthorexia have a fixation on healthy eating to such an extent that they damage their mental and physical wellbeing.

Signs of orthorexia include:

- Compulsively checking nutritional labels

- Concern regarding the healthiness of the ingredients

- Restricting intake of food groups

- Inability to eat anything but foods they have deemed healthy or pure

- Obsessively following food or healthy lifestyle blogs on social media

- Body image issues may or may not be present with this condition.

There is no treatment developed for orthorexia specifically but some eating disorder experts treat orthorexia as a type of anorexia or obsessive compulsive disorder.

Treatment may involve psychotherapy to increase the foods and exposure to anxiety-provoking foods.[18]

Eating Disorders in summary

People all over the world are affected by eating disorders whether it be living with someone who suffers from an eating disorder or having an eating disorder. In New Zealand, eating disorders are prominent with females having a higher risk of developing an eating disorder.

With the increased stress and isolation of COVID-19, there have been changes in the amount of eating disorders.

RELATED — Mental Health: The more we talk about it, the easier it gets

Worldwide Statistics

Eating disorders are a widespread issue with approximately 70 million people living with an eating disorder. The prevalence of eating disorders has increased to 7.8% in 2018 from 3.4% in 2000.[19]

Eating disorders occur more in young women than men

Eating Disorders in New Zealand

In New Zealand, roughly 103,000 struggle with an eating disorder and 70% of people with an eating disorder don’t have access to the help needed. This means that some New Zealanders and Australians consistently travel overseas to seek specialized treatment for their eating disorder.[21]

Research indicates that an early intervention of the eating disorder can lead to a better chance of recovery.[22]

| Symptoms | Anorexia Nervosa | ARFID | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge eating | Pica | Prader-Willi S. | Purging | Rumination Disorder | Orthorexia |

| Excessively limiting calories | ✔ | ||||||||

| Excessive exercise | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Vomiting after eating | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Dramatic weight loss | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal complaints | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Dizziness | ✔ | ||||||||

| Dry skin | ✔ | ||||||||

| Thinning hair | ✔ | ||||||||

| Muscle weakness | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Impaired immune function | ✔ | ||||||||

| Sleep problems | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Frequent episodes of eating large amounts | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| Bad breath | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Sore throat, tooth decay | ✔ | ||||||||

| Depressed mood | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Irregular Menstrual cycles | ✔ | ||||||||

| Feeling depressed | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Persistent eating of substances that aren’t food over a period of at least a month | ✔ | ||||||||

| Constipation | ✔ | ||||||||

| Stomach ulcers | ✔ | ||||||||

| Intestinal blockages | ✔ | ||||||||

| Lead poisoning or poor nutrition | ✔ | ||||||||

| Special facial features | ✔ | ||||||||

| Reduced physical development | ✔ | ||||||||

| Gaining weight | ✔ | ||||||||

| Limited cognitive development | ✔ | ||||||||

| Delayed motor and verbal skills | ✔ | ||||||||

| Purging Behaviour | ✔ | ||||||||

| Effortless regurgitation | ✔ | ||||||||

| Restricting intake of food groups | ✔ | ||||||||

| Inability to eat anything but foods they have deemed healthy or pure | ✔ |

Rise of eating disorders due to COVID-19

During COVID-19 people with eating disorders may be at risk of aggravating symptoms because of the increased levels of anxiety and stress due to self isolation.[23] Major economic and social changes as well as widespread uncertainty can cause stress which can induce disordered eating.

The worsening of eating disorders have been linked to altered routine, lack of control, social media pressures and loss of access to treatments due to pandemic lockdowns.[24]

In New Zealand, there was a confirmed pandemic-related increase in eating disorder services which followed similar trends worldwide.

There was an increased admissions for adults and referrals for children.[24]

Related Questions

1. Which eating disorder is hardest to treat?

Anorexia is one of the most deadly eating disorders due to mental illnesses because some people suffer in silence before seeking treatment.

Anorexia treatment is usually left to psychiatrists but the malnutrition that occurs as a result often requires medical intervention.[25]

2. How are eating disorders diagnosed?

Eating disorders can be diagnosed through many indications from tests such as physical exams which include slow breathing and slow pulse rates, laboratory tests which indicate organ failure due to malnutrition, and psychological evaluation where the mental health professional looks into eating habits and attitudes towards food and body image.[26]

3. Who should I talk to about eating disorders?

If you or a loved one suspect any eating disorder it is encouraged to seek medical advice from a doctor or a counsellor.

Most people with an eating disorder believe that they do not have an eating disorder.[27]

We will be having several more articles on Eating Disorders. So, if you would like to know when similar articles will be coming out, you can Subscribe to our Newsletter and we will let you know well in advance.

Tiana is an Associate Registered Nutritionist who has a passion for public health and education. Working towards a Master’s in Nutrition Practice with a Bachelor’s in Human Nutrition, Tiana has a personal interest in healthy heart nutrition and promoting positive lifestyle behaviours.

Tiana is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest news here at D’Connect.

References

(1) Eating Recovery Center. History of Eating Disorders – Eating Recovery Center [Internet]. Eating Recovery Center 2018 [cited 2021 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.eatingrecoverycenter.com/blog/February-2018/Let%E2%80%99s-Get-Real-About-the-History-of-Eating-Disorders

(2) Deans, E. A History of Eating Disorders [Internet]. Psychology Today. 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/nz/blog/evolutionary-psychiatry/201112/history-eating-disorders

(3) Muhlheim, L. When Did Eating Disorders First Appear? [Internet]. Verywell Mind. 2019 [cited 2021 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.verywellmind.com/history-of-eating-disorders-4768486

(4) Currin L, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Jick H. Time trends in eating disorder incidence. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005 Feb;186(2):132-5. Available from: http://www.brown.uk.com/eatingdisorders/currin.pdf

(5) Eating disorders – Symptoms and causes [Internet]. Mayo Clinic; 2018 [cited 2021 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/symptoms-causes/syc-20353603

(6) Bulik CM, Thornton LM, Parker R, Kennedy H, Baker JH, MacDermod C, Guintivano J, Cleland L, Miller AL, Harper L, Larsen JT. The Eating Disorders Genetics Initiative (EDGI): study protocol. BMC psychiatry. 2021 Dec;21(1):1-9. Available from: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-021-03212-3

(7) EDGI. About EDGI – EDGI [Internet]. EDGI. 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 18]. Available from: https://edgi.nz/about/

(8) Anorexia Nervosa [Internet]. NZ Eating Disorders Clinic. 2014 [cited 2021 Nov 26]. Available from: https://www.nzeatingdisordersclinic.co.nz/eating-disorders/anorexia-nervosa/

(9) Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID. Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) [Internet]. National Eating Disorders Association. 2017 [cited 2021 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/by-eating-disorder/arfid

(10) Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) [Internet]. NZ Eating Disorders Clinic. 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 26]. Available from: https://www.nzeatingdisordersclinic.co.nz/eating-disorders/arfid/

(11) Bulimia Nervosa [Internet]. NZ Eating Disorders Clinic. 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.nzeatingdisordersclinic.co.nz/eating-disorders/bulimia-nervosa/

(12) Binge Eating Disorder [Internet]. NZ Eating Disorders Clinic. 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.nzeatingdisordersclinic.co.nz/eating-disorders/binge-eating-disorder/

(13) Christiansen, S. What Is Pica? [Internet]. Verywell Health. 2012 [cited 2021 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.verywellhealth.com/pica-5083875

(14) Felman A. What is Prader-Willi syndrome? [Internet]. Medicalnewstoday.com. Medical News Today; 2018 [cited 2021 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/182287#treatment

(15) Sutton, J. Purging Disorder: What Is It? [Internet]. Healthline. Healthline Media; 2019 [cited 2021 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/eating-disorders/purging-disorder#symptoms

(16) Rumination syndrome – Symptoms and causes [Internet]. Mayo Clinic. ; 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/rumination-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20377330

(17) National Eating Disorders. Rumination Disorder [Internet]. National Eating Disorders Association. 2017 [cited 2021 Nov 25].

(18) National Eating Disorders. Orthorexia [Internet]. National Eating Disorders Association. 2017 [cited 2021 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/by-eating-disorder/other/orthorexia

(19) Single Care. Eating disorder statistics 2021 [Internet]. The Checkup. SingleCare; 2020 [cited 2021 Nov 20]. Available from: https://www.singlecare.com/blog/news/eating-disorder-statistics/

(20) ANAD. Eating Disorder Statistics – General & Diversity Stats [Internet]. National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 20]. Available from: https://anad.org/eating-disorders-statistics/

(21) Statistics & Outcome Data – Recovered Living NZ [Internet]. Recovered Living NZ. 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 26].

(22) EDANZ [Internet]. Ed.org.nz. 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 26]. Available from: https://www.ed.org.nz/getting-help/what-to-do/

(23) Touyzs, S., Lacey, H., & Hay, P. (2020). Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8(1), 19.

(24) Hansen SJ, Stephan A, Menkes DB. The impact of COVID-19 on eating disorder referrals and admissions in Waikato, New Zealand. Journal of eating disorders. 2021 Dec;9(1):1-0.

(25) Makris N. Why Severe Anorexia Is so Difficult to Treat [Internet]. Healthline. Healthline Media; 2015 [cited 2021 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health-news/why-severe-anorexia-is-so-different-to-treat-060415#Doctors-Dont-Get-It

(26) Higuera V. Diagnosing an Eating Disorder [Internet]. Healthline. Healthline Media; 2014 [cited 2021 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/eating-disorders-diagnosis#psychological-evaluations

(27) Mental Health Foundation. Eating disorders [Internet]. Mentalhealth.org.nz. 2019 [cited 2021 Nov 25]. Available from: https://mentalhealth.org.nz/conditions/condition/eating-disorders