James Nelson

(BA (Hons.) PGCE, PGDES, PG Dip. Counselling, Master of Counselling)

Carly Hanna

BSc (Human Nutrition and Psychology)

Depression is on the rise, and recent studies reported an increase of 20-25% following the COVID-19 pandemic and the measurements that many governments put in place as means of precaution.

Our goal in this, and subsequent articles, is to better understand depression, and slowly unravel this condition that many find debilitating.

First, let us start by trying to provide a best description for depression.

How to best describe depression (to your loved ones)?

Depression is an extremely common ‘mood disorder’ that affects hundreds of millions of people globally.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (the ‘DSM-5’) provides a comprehensive summary of how and when depression is diagnosed, usually by speaking to psychiatrists, although GPs often initially screen patients for depression.

Depression is more than the usual ‘ups and downs’ that we all go through

Generally, symptoms have to be present for more than two weeks before an accurate diagnosis can be made.

Signs and symptoms of depression

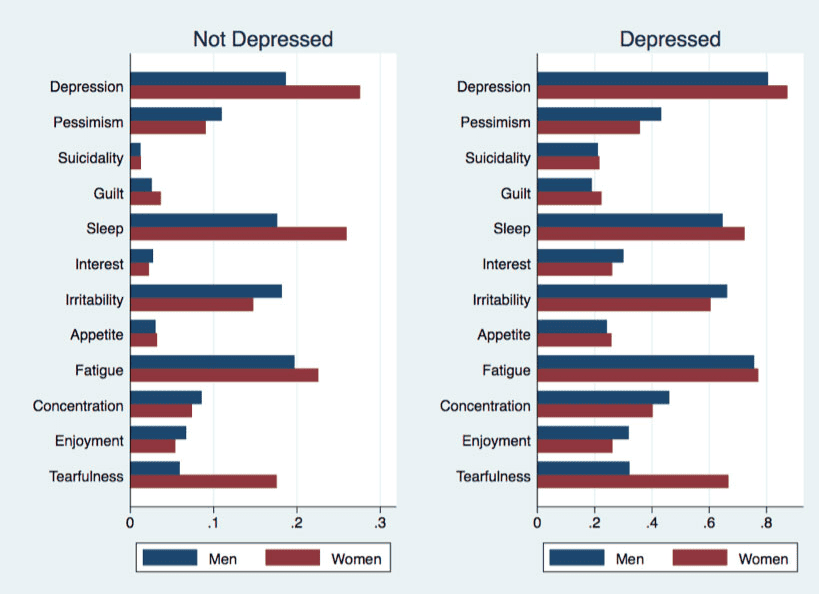

Depression could be said to be a name for a very specific and unique state, with distinct biological signs and specific symptoms such as irregular sleep, exhaustion and extremes of appetite.

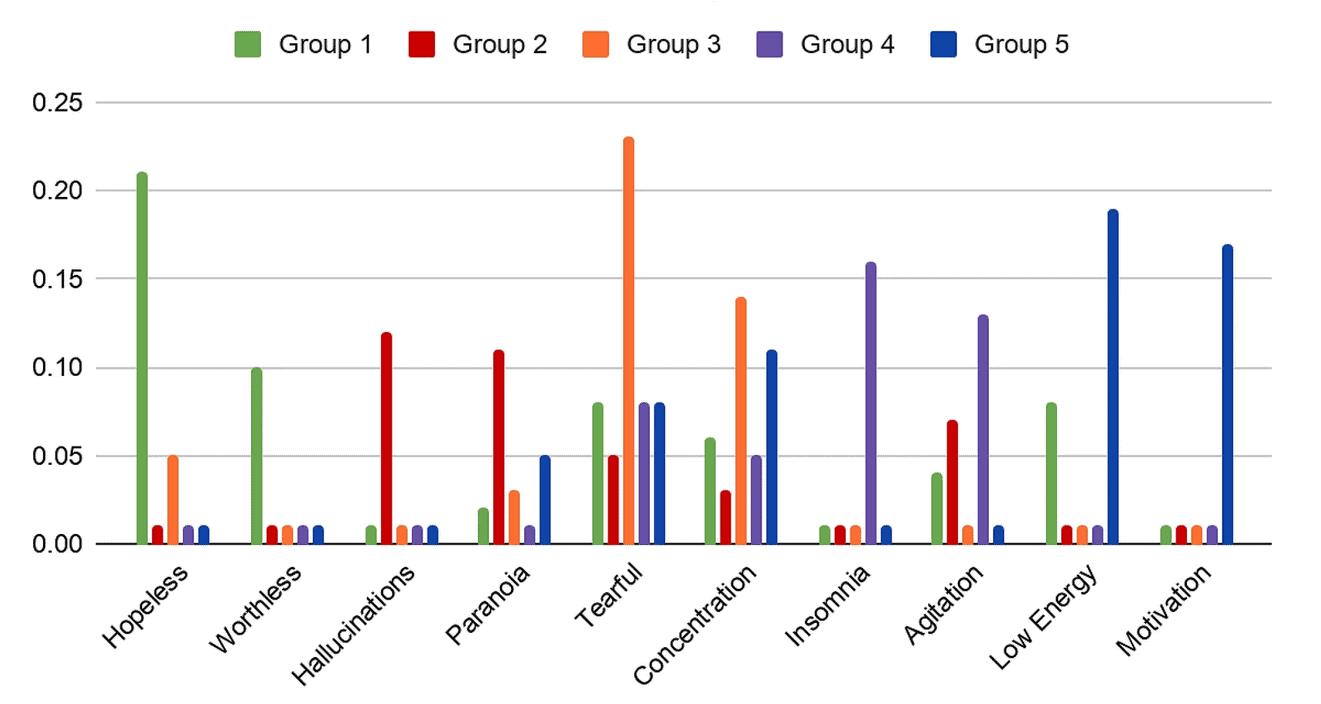

Source: Stewart, R. Identifying subtypes of depression in clinician-annotated text: a retrospective cohort study. (2021)

Appetite

Changes in appetite during a depression can be very varied. Patterns of extreme overeating are very common as are patterns of undereating.

Chronic physical pain

Physical pain may accompany depression, and may vary from vague aches to more chronic pain in the joints and limbs.

Mood

“Moods” are more prolonged than particular or sudden bursts of feeling. They can take longer to ‘come on’, and longer to ‘go away’.

Low or lost interest in activities

During a depression a person often reports an inability to enjoy much, or anything at all. This includes activities that used to bring joy or satisfaction.

Sleep

Insomnia, not unnaturally, in and of itself can lower mood. Prolonged low mood though can also trigger bouts of insomnia, as well as bouts of extreme hyperactivity. Variations of this are many.

RELATED — Different types of sleep: Which one do we need the most?

Feeling guilty

Guilt is a state or feeling often reported during depression. Guilt can be either existential (necessary or functional guilt, for example if behaviours run at odds to values) or neurotic, which has no apparent cause.

People often report feeling guilty for being ‘weak’ or asking for help.

Changes in weight

As mentioned above, prolonged under or overnourishment can lead over time to severe weight loss or gain, which in turn can exacerbate depressive episodes.

Depression can sometimes slow digestion too, which may lead to gastrointestinal problems.

Low energy and fatigue

Even if a person reports getting enough sleep, they may still feel extremely tired or worn out during depressive episodes.

Getting up in the morning, or showering or brushing teeth may seem extremely difficult or impossible. Observers or caregivers often notice these changes, and sometimes find this difficult to bring up.

Focus and concentration

Not unnaturally, and particularly if exhaustion is prevalent, people often report an extreme inability to focus or concentrate on anything for any reasonable length of time during a depressive episode.

Anxiety

Anxiety in various forms is very often the close bed-fellow of depression.

Understandable worry about lack of sleep can lead to poor sleep, which can lead to exhaustion, leading to more depression and exhaustion — the variations of loops and spirals are all quite common.

Thoughts of death and self-harm

These can be very common during depressive episodes. Suicidal ideation (thinking about suicide) is very different and to be distinguished from clear, planned suicidal intent or attempts.

Deliberate self-harm separate from suicidal intent may also co-exist within depressed states.

Libido

In some individuals dealing with depression there may be a complete loss of interest in any sexual activity whatsoever. The reverse may also be true as some people report hypersexuality in depression.

Irritability and frustration

Although many clients lack the capacity for healthy experiences of anger and its expression during depressive episodes, others report feeling angry all the time, often with the depressed state itself.

Source: Gennaro, C. A model-driven approach to better identify older people at risk of depression. Ageing and Society. (2019)

Though these are the main markers of depression, there are also other ones and we’ll cover them in more detail in our next article.

What are the common causes of depression?

Triggers or causes of depression can be many. Some practitioners describe depressive episodes as ‘reactive’ or ‘situational’, suggesting that events such as bereavement and other types of loss and change such as redundancy, can result in depressive episodes.

Traumatic events and experiences

It’s sometimes surprising to recall that the medical world ‘officially’ recognised post-traumatic stress disorder as recently as 1980.

Understandably, the field of trauma is a complex one. Put briefly, traumatic incidents may be defined as any experiences that are, or are perceived as, life-threatening to oneself or others. For example, witnessing acts of violence, or even hearing or reading about them.

Not surprisingly, exposure to traumatic experiences can often lead to prolonged bouts of depression. Traumatic experiences in childhood may manifest many years later in depressive episodes.

People may experience Type 1 and Type 2 Traumatic events, which can understandably lead to depression.

By Type 1 I am categorising sudden, usually one-off events such as accidents, wars, floods, famines (obviously these can become Type 2 events) sexual assaults and other violent crimes.

Type 2 traumatic events can be more subtle and persistent, such as the impact of bullying, poverty, harassment, discrimination, as well as others. In short any event or events that can ‘threaten’ the sense of a person’s physical, emotional and general psychological safety.

Stressful events and experiences

Moving house, unemployment, bereavement, being displaced from countries can lead to depressive episodes.

These are not to be ignored with existential issues such as lack of purpose or meaning. Poverty, discrimination in all its forms, bullying can also feed or cause depression.

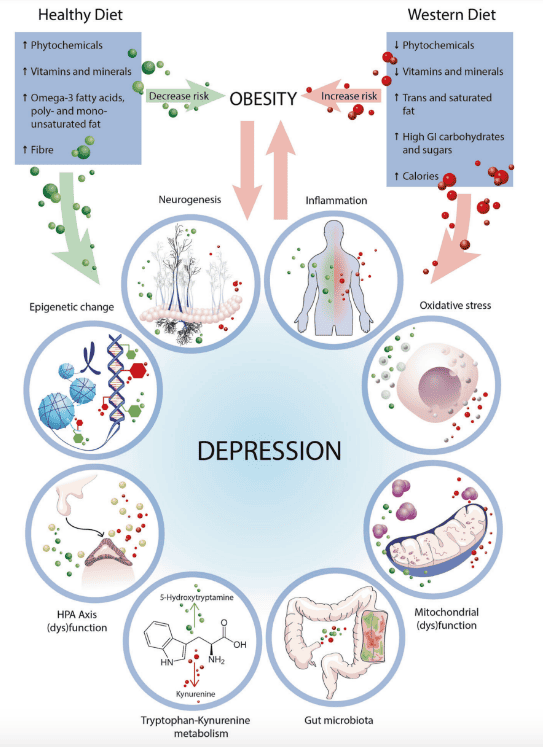

Malnutrition, hunger, illness

Poor nutrition, hunger, illness and disability may lead to depression.

These are all complex fields in themselves, and organic reasons for depression can never be ignored.

Nutrition can play a role in the onset, severity and duration of depression.[1] There are certain vitamins and minerals that are important for our brain health and mental health, including:

- Omega-3 fatty acids

- B-vitamins

- Iron

- Vitamin D: The sunshine hormone for stronger bones

- Zinc: For immunity, skin health and libido

- Vitamin C: Immunity and Collagen booster

However, the link between diet and depression is multifaceted and complex.

Along with not getting enough nutrients in our diet, there are also biological factors influenced by diet, which can contribute to the risk of depression. This can include:

- illness or disability

- inflammation

- oxidative stress

- stress hormones (HPA axis dysfunction)

- bacteria in our gut

Source: Marx, W., Lane, M., Hockey, M. et al. Diet and depression: exploring the biological mechanisms of action. (2020)

Research has shown that malnutrition in people with severe depression can be up to 15.5 times higher than in people without depression.[2]

While malnutrition, hunger and illness can lead to depression, depression can also contribute to malnutrition due to having symptoms such as poor appetite and skipping meals. This can, understandably, make it difficult to meet nutrient requirements.

Medication

Clients sometimes say that taking prescription medication for various ‘mental health conditions’ causes them to feel more depressed (because, for example, of side effects) whereas others say they rely on medication.

Each individual narrative of depression is different

Sometimes, depression is literally, as the word suggests, something ‘pushed down’ so that all common feelings are simply ‘not felt’.

This is often not a conscious decision ‘chosen’ by the sufferer but “imposes itself, turning a once-vibrant emotional landscape into arid desert.”[3]

Who is most at risk of depression?

One could argue that depression is as old as civilization itself. Terrible ‘things’ can and do happen to anyone, so it could be said that anyone can be prone to depression.

Some of the contributors to depression may be based on

- age

- gender

- genetics and family history

- marital status

- medical condition and illness

- medication use

- race

- socioeconomic status

- substance use

- adverse childhood experiences

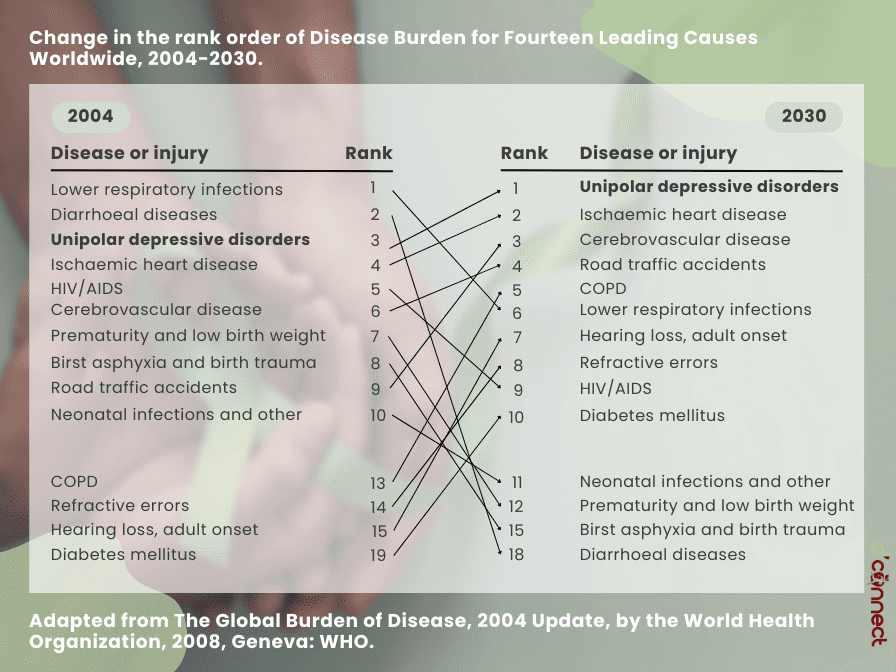

Major studies point to its increase globally, despite our increased knowledge about the condition.[4]

For example, the World Health Organisation predicts a change in the rank order of disease burden for fourteen leading causes worldwide; “Unipolar Depressive Disorders”, ranked 3rd leading cause in 2004, are predicted to be the number one cause by 2030.[5]

Research conducted since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic clearly shows that depression (and anxiety) rates climbed across the globe, with depression rates increasing by 28% according to a systematic review led by Alize Ferrari, a lead researcher at the Queensland Centre for Medical Health Research in Australia.

This study estimated that there were about 3,153 total cases of major depressive disorder per 100,000 people worldwide in 2020, and that after adjusting for the rises associated with the pandemic.[6]

Related Questions

1. Can people recover and “repair” after the depression?

Yes. Some clients report that depression ‘lifts’ out of a combination of medication and talk (or other) therapy, self-help strategies, dietary tweaks, situational changes such as job, location or relationship shifts.

I am (hopefully, healthily) sceptical of catch-all or ‘one size fits all’ treatment paths for depression.

2. Does depression affect IQ?

A study “Effects of major depression on estimates of intelligence” suggests that depression can lower the brain’s ability to function appropriately.[7]

3. What foods are linked to depression?

Foods that are typically part of the “Western Diet”. These would include

- processed foods

- foods high in trans and saturated fats

- foods with high GI (glycaemic index), such as carbohydrates and sugars[1]

This may be because these foods lack nutrients that are essential for brain and mental health.

RELATED — The Healthy Plate Model: Essentials of Healthy Eating

4. What is the survival rate of depression?

Depression can be and is treatable.

The current research suggests that 96.5% of individuals recover from depression.[8]

5. What kind of exercise is good for depression?

Exercise is a behavioural intervention that has shown great promise in alleviating symptoms of depression.

In my experience, diet and exercise are among many important levers that can shift persistent moods.

Depression is often marked by extreme under activity (and occasionally, over activity – in these cases, I try to get clients to slow down!) so getting moving can be very important.

I regularly consult a registered dietician and believe that anything we put into our systems can affect mood, momentarily or over a longer period.

In short, a holistic (and culturally sensitive) approach is usually beneficial.

A Personal Note

People sometimes ask me if I ‘know’ depression from ‘the inside’. If appropriate I sometimes do share a personal experience if it is to demonstrate a point and with the intention of aiding a client’s recovery or helping them become more curious about their situation and life.

For me, ‘recovery’ was and is a complex blend of diet, exercise, existential searching, therapeutic intervention and a broader education around wellbeing generally.

I don’t think enough attention is given to the highly individual ‘interior lives’ and stories of clients. The often-fatigued General Practitioner, for example, is usually forced to ‘screen’ patients in 10-15 minutes and then make informed triage decisions.

I can conclude therefore that I have a huge ‘bias’ towards finding the right therapist who can accompany clients on their journey of recovery, and discovery. I encourage people to ‘shop around’ until they find the right fit.

The following resources may be useful:

Community based support

- Youthline: 0800 376 633 or text 234

- Te Haika triage: 0800 745 477

- Anxious/depressed: text 1737 to talk to a trained counsellor 24/7

- Depression Line: 0800 111 757

- Alcohol and Drug Helpline: 0800 787 797

- Family Violence info line: 0800 456 450

- Health line: 0800 611 116

- Lifeline Aotearoa nationwide: 0800 543 354

- Warmline (Mental Health Peer Support): 0800 200 207

- Victim Support: 0800 842 846

- Outline: LGBTIQ- affirming support line and face to face counselling- 0800 688 5463

- Suicide crisis helpline: 0508 828 865

- Anxiety phone line: 0800 269 4389

James is a qualified, trained Counsellor and full member of the New Zealand Counsellors’ Association. He has been counselling in various settings for over 20 years, and has been running a private practice for the past seven years. He has also been clinically supervising other therapists for over 15 years, as well as being involved with facilitating and training.

James holds Post-Graduate Diplomas in Education, Education and Behavioural Studies, Counselling, and a Master’s Degree in Counselling. In previous ‘lives’ he has also been a high-school teacher, Resource Teacher of Learning and Behaviour, and residential Social Worker; James has also done internships in secure psychiatric units in the UK and for a while ran a family ‘group’ home for ‘unplaceable’ children in the care of local authorities in the UK.

His Master’s research focused on the efficacy of Auto-Ethnographic writing and approaching the transformation of grief and trauma through therapeutic autobiography. He has wide experience of most imaginable situations and circumstances that occur in the therapeutic context such as grief, panic attacks, anxiety and its management, depression, separation, communication and assertiveness, stress, mediation, managing conflict and anger, parenting issues, addiction, school and education issues, self-esteem, confidence and all aspects of inter and intra-personal relationships. James is eclectically trained and person-centred in his approach.

James remains fiercely invested in helping people find direction and clarity through counselling — a partnership and process of discovery whereby the counsellor gives the time, attention, understanding and counselling skills to the client who may want to explore a problem, make a decision about something or someone, or perhaps learn and experiment with new ways of being and living.

Carly’s goal is to become a registered psychologist with a focus on self-care – food, exercise, and sleep. She has a special interest in various mental health disorders, plant-based diets, and the relationship between food and mood.

Through evidence-based research, holistic approach to health and personal experience, Carly hopes to empower others’ well-being.

Carly is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect.

References

(1) Marx, Wolfgang, Melissa Lane, Meghan Hockey, Hajara Aslam, Michael Berk, Ken Walder, Alessandra Borsini, et al. “Diet and Depression: Exploring the Biological Mechanisms of Action.” Molecular psychiatry 26, no. 1 (2021): 134–150. DOI: 10.1038/s41380-020-00925-x

(2) Vafaei Z, Mokhtari H, Sadooghi Z, Meamar R, Chitsaz A, Moeini M. Malnutrition is associated with depression in rural elderly population. Journal of research in medical sciences: the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. 2013 Mar;18(Suppl 1):S15. PMCID: PMC3743311

(3) Matē, G & Matē, D, The Myth of Normal – Trauma, illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture, Avery, New York, 2023, page 254.

(4) Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR).

(5) Rottenberg, J, The Depths – the Evolutionary Origins of the Depression Epidemic, Basic Books, New York, 2014.

(6) Santomauro, D.F, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Volume 398, ISSUE 10312, P1700-1712, November 06, 202. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

(7) Sackeim, H, A. et al. Effects of major depression on estimates of intelligence. (2008) Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology Pages 268-288. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01688639208402828

(8) Pratt LA, Druss BG, Manderscheid RW, Walker ER. Excess mortality due to depression and anxiety in the United States: results from a nationally representative survey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016 Mar-Apr;39:39-45. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.12.003. Epub 2015 Dec 18. PMID: 26791259; PMCID: PMC5113020. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5113020/

Other bibliography

(1) Hari, J, Lost Connections, Bloomsbury Circus, London, 2018.

(2) Hayes, S, A Liberated Mind, Random House, London, 2019.

(3) Jacobs, M, The Presenting Past – The Core of Psychodynamic Counselling and Therapy, Open University Press, Maidenhead, 2009.

(4) Leader, D, The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia and Depression, Penguin, London, 2008.

(5) Matē, G, When the Body Says No – The Cost of Hidden Stress, Scribe, Victoria, 2022.

(6) Matē, G & Matē, D, The Myth of Normal – Trauma, illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture, Avery, New York, 2023.