Kathy Mcilwain

(MEd, BSN, PGDip Mental Health Nursing)

Stress is our body’s response to mental, emotional and physical stimuli that we find in our environment.

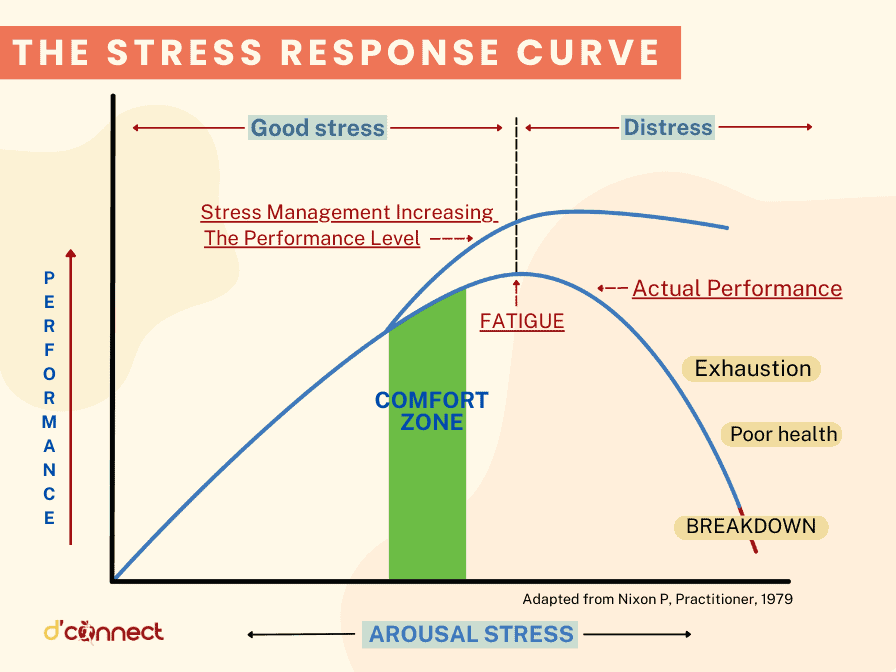

Stress in limited quantities and duration makes us better than our previous selves. We grow, develop and become stronger and resilient, either mentally, emotionally or physically.

However, for many there is simply no “on-and-off” switch for stress, and this is where something that is innately positive and protective can become very destructive.

What is stress?

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines stress as “a state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation. Stress is a natural human response that prompts us to address challenges and threats in our lives.”[1]

Stress can be positive when it motivates us to study for an exam or prepare for a family event such as a birthday party or a wedding.

Stress can be negative if we are stressed to a degree that we cannot relax and our daily functioning is affected, such as difficulty eating, sleeping and thinking clearly as well as increased irritability, headaches and nausea.

Stress is normal and everyone experiences it

There are two types of stress — acute stress and chronic stress.

Acute stress can be related to a one-off event experienced suddenly or a stressor that is short-term such as a month or less.

Examples of acute stressors are experiencing an illness, such as a cold or the flu, a short visit from family or friends, or a temporary change in employment such as stepping up when the boss is away. With acute stress that has a definitive endpoint, the body has an opportunity to recover.[2]

Chronic stress lasts more than a month without an opportunity for the body to return to a non-stressed state of relaxation. This can often affect all areas of our lives, including productivity, relationships, and emotional and physical health.[3]

Examples of chronic stressors are changing jobs, the birth of a child, retirement, or the death of a close friend or family member.[4]

We can experience chronic stress from positive and negative events in our lives.

Acute and chronic stress from positive and negative stressors can lead to physical illness, burnout, increased anxiety and depression.

Chemistry behind stress

The limbic system of our brain is responsible for the most basic functions such as

- survival

- food security

- reproduction and care for our children

to more complex functions that include

- learning

- memory

- motivation

- emotions[5]

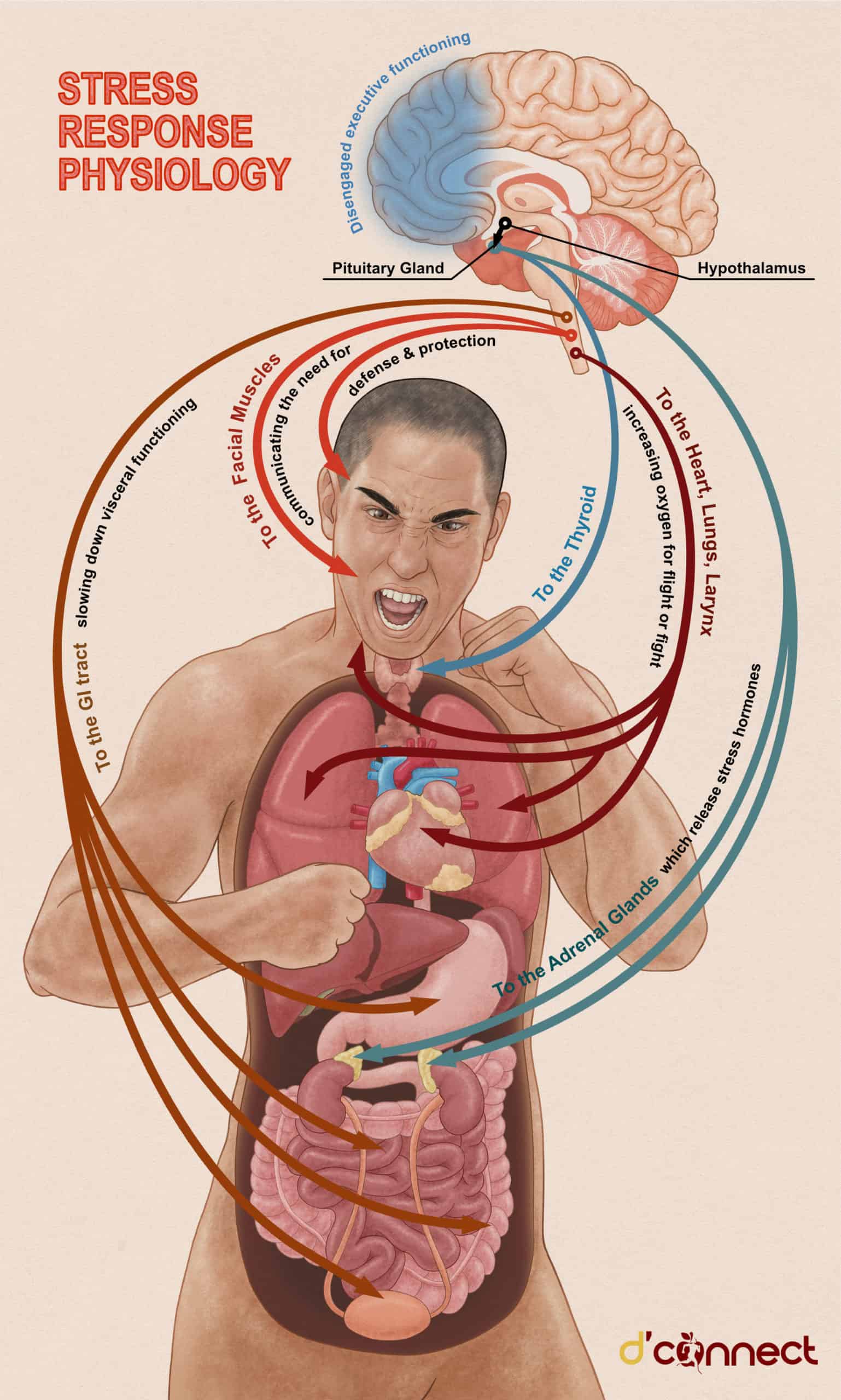

Based on stimuli/stress that originate from our environment, the limbic system (behaviour and emotions) has the ability to bypass the frontal cortex (logic and reasoning) and allow for an instant reaction — fight-or-flight.[5]

The most important job of the brain is to ensure our survival. Everything else is secondary.

— Bessel Van Der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score

The limbic system, also known as the mammalian brain, communicates with the brain and body by releasing hormones and neurotransmitters that activate the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system when we are stressed or in danger.

An important part of the limbic system is the amygdala, whose specific purpose is to recognize potential danger and threats, and coordinate the release of hormones and neurotransmitters for us to respond instantly, if there is a need.[5]

The frontal cortex is the area of the brain just behind the forehead that uses information from the limbic system and is responsible for executing higher functions and essential daily activities such as reasoning, sequencing of complex activities, voluntary movement control, organising, problem solving, and personality expression.[6]

By the time our frontal cortex is aware of what is happening and uses this information to judge or reason, we are already responding.

The flood of powerful stress hormones that include cortisol and adrenaline cause an increase in

- heart rate

- blood pressure

- rate of breathing

to prepare us to fight, run or freeze.

Under normal circumstances, once the stressor has passed, the response is finished and the body recovers.

However, if the stress is ongoing the body is triggered to defend itself continuously, and this causes heightened agitation and arousal.

The importance of stress in our evolution

Stress response was an important and essential tool for invoking fight, flight or freeze in our ancestors who had to be ready to respond with no notice to threats such as predators.

Stress and the drive to survive meant that our primitive brain responded by releasing stress hormones with the amygdala bypassing the frontal cortex and allowing for an immediate response to fear.

The benefit of immediate response without the need to think and make decisions meant speed and agility.

In today’s times, however, the threat of predators is replaced by many other types of smaller stressors, from which sometimes we find it impossible to run away.

Modern times and stress

The predators today are different but still stressful. Some examples of modern stressors are receiving dozens of emails per day and drowning in the sensory overload that can happen from following multiple social media platforms and news sites.

An average individual in the Western society daily “consumes” about 34 gigabytes of data and information, which is 350 percent more than in the 1980s.[7]

Children and teenagers are particularly affected by modern stressors. The American Psychiatric Association (2000) reported that normal children today report more anxiety than child psychiatric patients in the 1950s.[8]

Major stressors for children, apart from worrying about schoolwork, are

- spending time online

- peer group pressures

- bullying

- puberty

- money problems in the family

- seeing parents go through divorce or separation

- living in an unsafe neighbourhood[9]

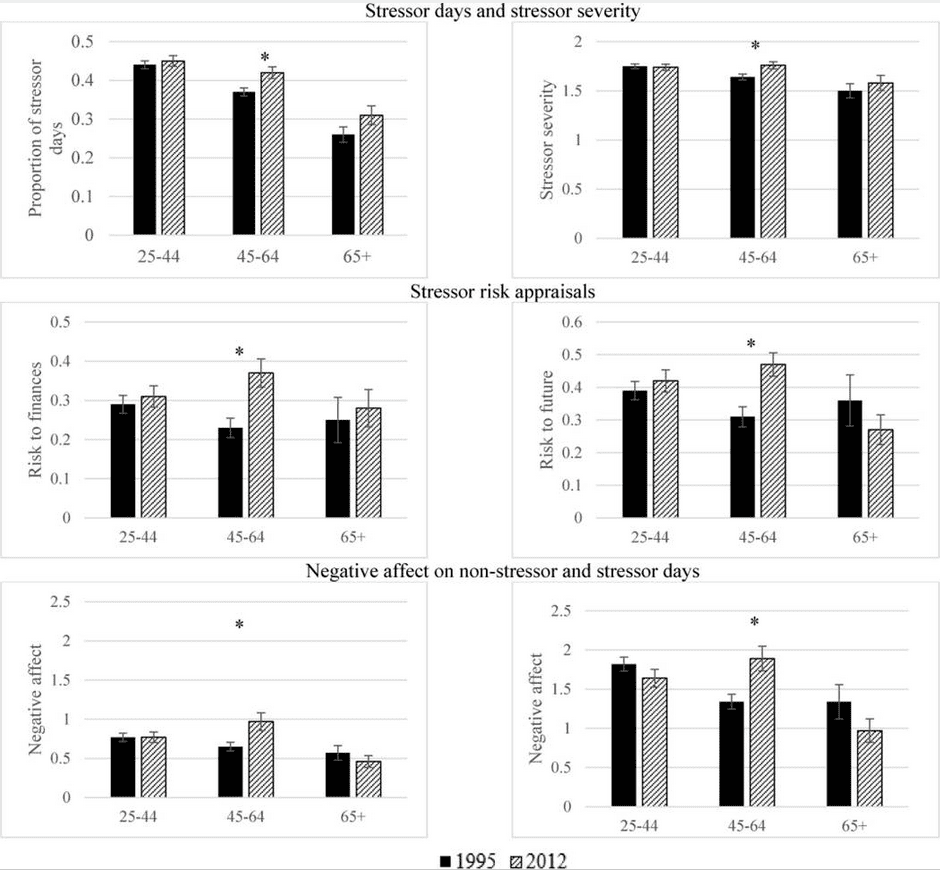

A study from 2020 found that adults in the 2010s reported a higher stress and great number of daily stressors, when compared to the same age groups in the 1990s.[10]

Today the fear of predators and getting eaten is replaced by career pressure, finances and body-image concerns.

Young adults find themselves overloaded with information that repeatedly brings up questions “Am I thin enough?” and “Why don’t I look like that?”[11]

It seems that we are getting more stressed and less resilient with each decade that has passed.

Signs and Symptoms of stress

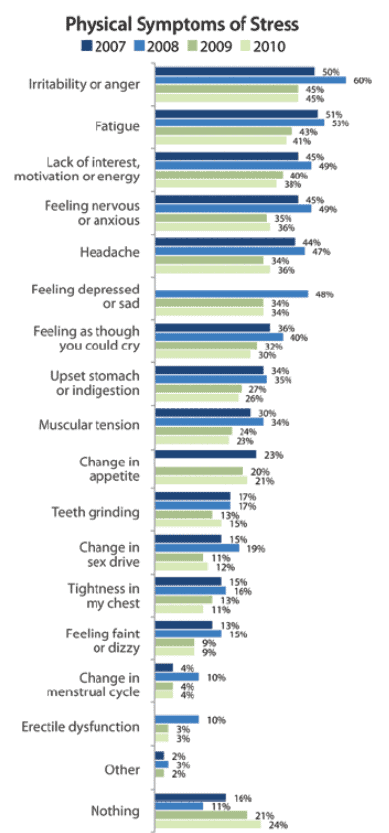

Known symptoms of stress include:

- Anxiety

- Arrhythmia and palpitations

- Change in appetite causing weight loss or gain

- Cognitive issues (difficulty concentrating or focussing)

- Decreased immunity (infections and colds)

- Emotional and physical withdrawal

- Gastrointestinal issues (IBS, chronic inflammation, ulcers)

- Hair loss/premature graying

- Headaches

- Hypertension

- Irritability

- Insomnia and poor sleep

- Increased alcohol or drug use

- Low energy

- Lowered sex drive

- Muscle and joint aches

- Panic attacks

- Skin issues (eczema, exacerbation of psoriasis, hives)

We will cover this in more detail in our next article.

Stress can cause a myriad of health issues

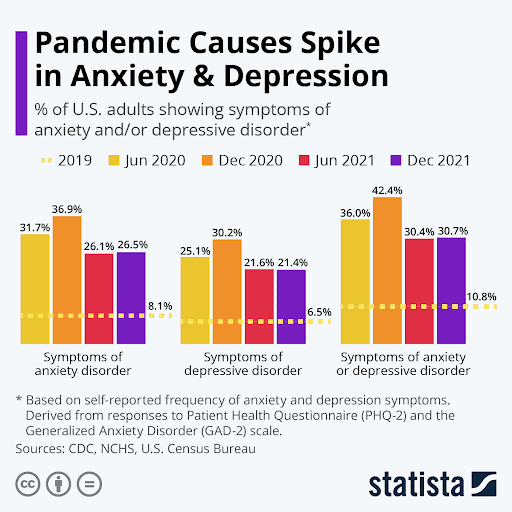

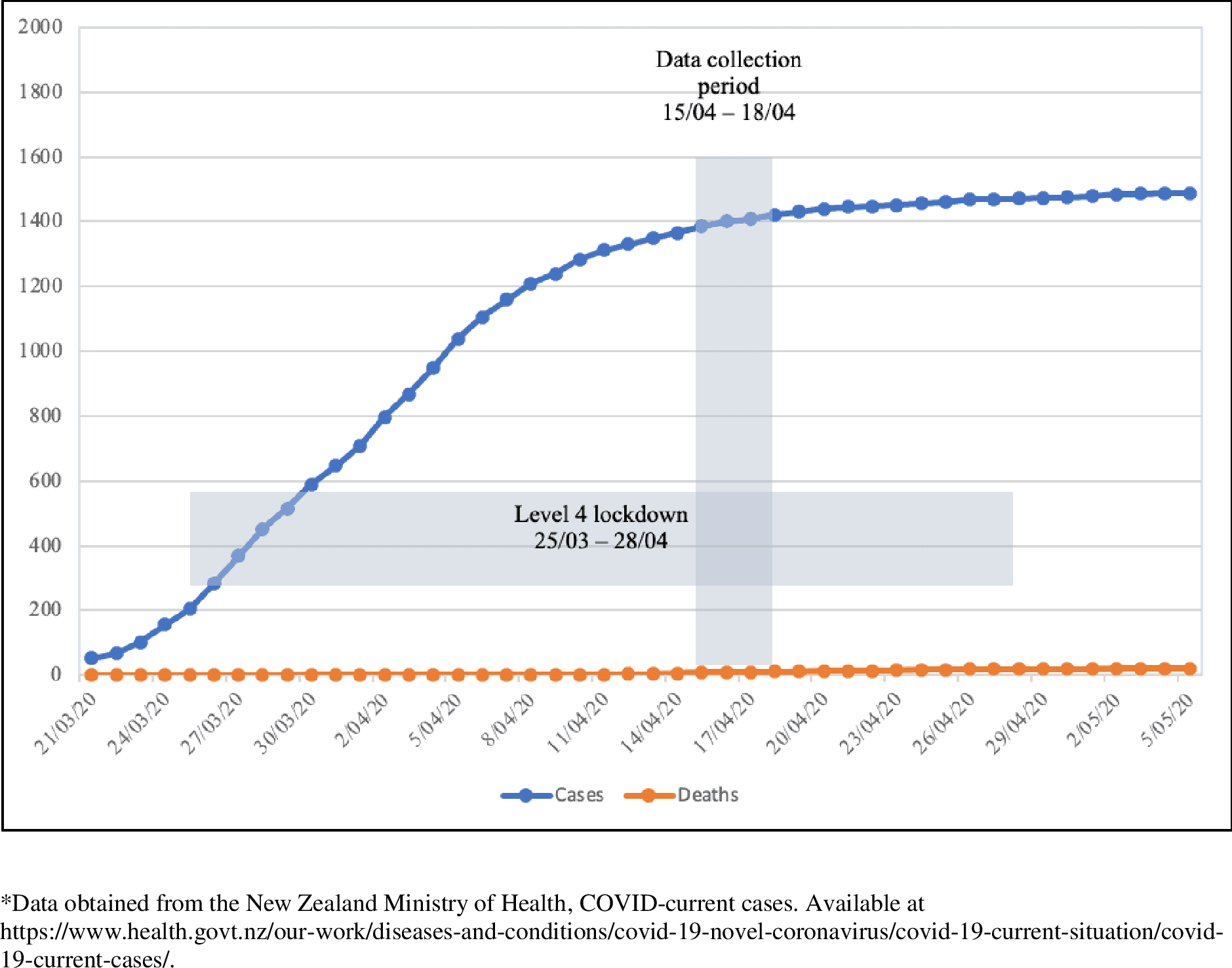

It is also important to mention the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdowns, where there was a sharp increase in symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults.[12]

Below we can see the data and statistics from New Zealand, recorded in April 2020, when the first lockdown lasted for 33 days.[13]

Given that New Zealand had several lockdowns from 2020-2022, we are yet to receive the latest figures on the effects of lockdowns on psychological wellbeing.

Long-term physical effects of stress

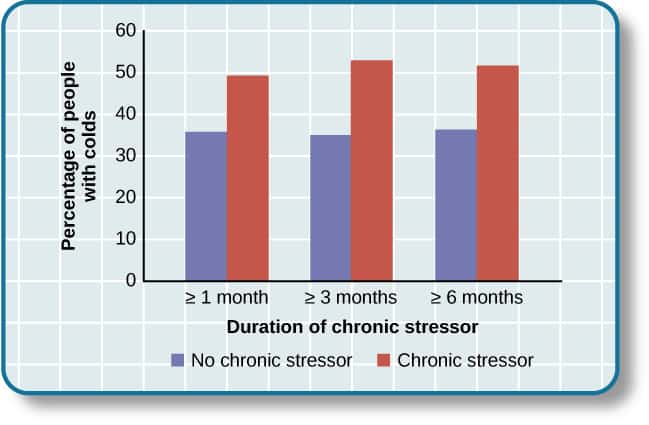

Chronic or long-term stress has been recorded as having a negative impact on our immune system.

For example, releasing stress hormones can inhibit the production of lymphocytes, which are important when the body is generating an immune response.[14] We can see that below for the duration of colds.

Overtime, chronic stress can cause far more devastating effects on our health that can result in:

- Anxiety and depression

- Cardiovascular disease

- Cancer

- Chronic pain

- Cushing’s disease

- Diabetes

- Eating disorders

- Erectile dysfunction

- Obesity

This and more will be the topic of one of our following articles.

Related Questions

1. What does stress do to our brain?

Stress affects the fight, flight or freeze of the sympathetic nervous system by alerting the amygdala to danger and can temporarily disable the recovery mechanisms of the sympathetic nervous system.

This can cause physical and mental exhaustion.[3,5]

2. Is stress related to burnout?

When stress is chronic it can lead to burnout.

With chronic stress our body does not get an opportunity to restore homeostasis, which is a period of reduced stress hormones.[5]

3. How do I get my body/mind out of fight-or-flight mode?

There are several usual techniques such as

- talk therapy

- meditation

- chanting

- yoga

- massage

- medication

and other sensory modulation techniques such as aromatherapy and grounding that support mindfulness.[5]

RELATED — Introduction to Mindfulness: Enjoy the present moment and appreciate life

For more similar articles, we suggest browsing our Mental Health page.

Kathy is originally from the United States and trained at University of West Florida in Pensacola, Florida. She has been a nurse for 30 years and spent the early years of her nursing career in the United States Navy. She is registered with the Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ) and is a Provisional Member of the New Zealand Association of Counsellors (NZAC).

Kathy has practiced in oncology, palliative care and mental health as well as worked as a Community Mental Health Nurse for most of the past 25 years in New Zealand. Currently, she is studying with the University of Waikato for a Master of Counselling, Narrative Therapy.

Kathy is knowledgeable in the physiology of the mind-body connection and is passionate about helping people to achieve their dreams and desires. She loves a good story and works in community mental health and in private practice.

Kathy believes that relationships are a key to everything and certain individuals come into our lives for a reason, and that might sometimes be to help us re-story our lives.

References

(1) World Health Organisation, 21 February 2023. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress#:~:text=Stress%20can%20be%20defined%20as,experiences%20stress%20to%20some%20degree

(2) VeryWellMind, 19 March 2021, All About Acute Stress: What you should know about acute stress. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/all-about-acute-stress-3145064

(3) Harvard Health Publishing, 06 July 2020, Stay Healthy: Understanding the stress response. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response

(4) Yale Medicine, accessed 14 May 2023, Chronic Stress Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/stress-disorder

(5) Van Der Kolk, B. (2014.) The Body Keeps the Score. Penguin Books.

(6) Healthline, 20 April 2020, What to Know About Your Brain’s Frontal Lobe. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/frontal-lobe

(7) Bilton, Nick. (January 2021). Part of the Daily American Diet, 34 Gigabytes of Data. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/10/technology/10data.html?auth=login-google1tap&login=google1tap

(8) American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Studies Show Normal Children Today Report More Anxiety than Child Psychiatric Patients in the 1950’s. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2000/12/anxiety

(9) National Institutes of Health, Medline Plus, accessed 23 May 2023, Stress in Childhood. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002059.htm

(10) Almeida, D. M., Charles, S. T., Mogle, J., Drewelies, J., Aldwin, C. M., Spiro, A. III, & Gerstorf, D. (2020). Charting adult development through (historically changing) daily stress processes. American Psychologist, 75(4), 511–524. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7213066/

(11) US News, 14 September 2017, 5 Modern Stressors and How to Handle Them. Retrieved from https://health.usnews.com/wellness/mind/articles/2017-09-14/5-modern-stressors-and-how-to-handle-them

(12) Statista. (15 February 2022). Pandemic Causes Spike in Anxiety & Depression. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/chart/21878/impact-of-coronavirus-pandemic-on-mental-health/

(13) Every-Palmer S, Jenkins M, Gendall P, Hoek J, Beaglehole B, et al. (2020) Psychological distress, anxiety, family violence, suicidality, and wellbeing in New Zealand during the COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE 15(11): e0241658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241658

(14) Psychology. Stress and Illness. Retrieved from http://pressbooks-dev.oer.hawaii.edu/psychology/chapter/stress-and-illness/