Bernadeth Atrinindarti

MAppSc (Advanced Nutrition Practice)

Jump to:

- What is Vitamin A?

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Different types of Vitamin A

- Health Benefits

- Health Claims

- Best sources of Vitamin A

- Daily requirements and intake

- How to take Vitamin A

- Signs and symptoms of deficiency

- Risks and side effects

- Interactions - herbs and supplements

- Interactions - medication

- Summary

- Related Questions

While in today’s time the B vitamins are getting more spotlight than usual, it is important to know and understand the impact vitamin A has on our growth, development and health.

This is because deficiency in vitamin A can result in problems with:

- Eye health and vision

- Weakened immunity and increased risk of infection

- Skin and hair

- Reproductive health

and a few other conditions that we talk about in more detail in the article.

What is Vitamin A?

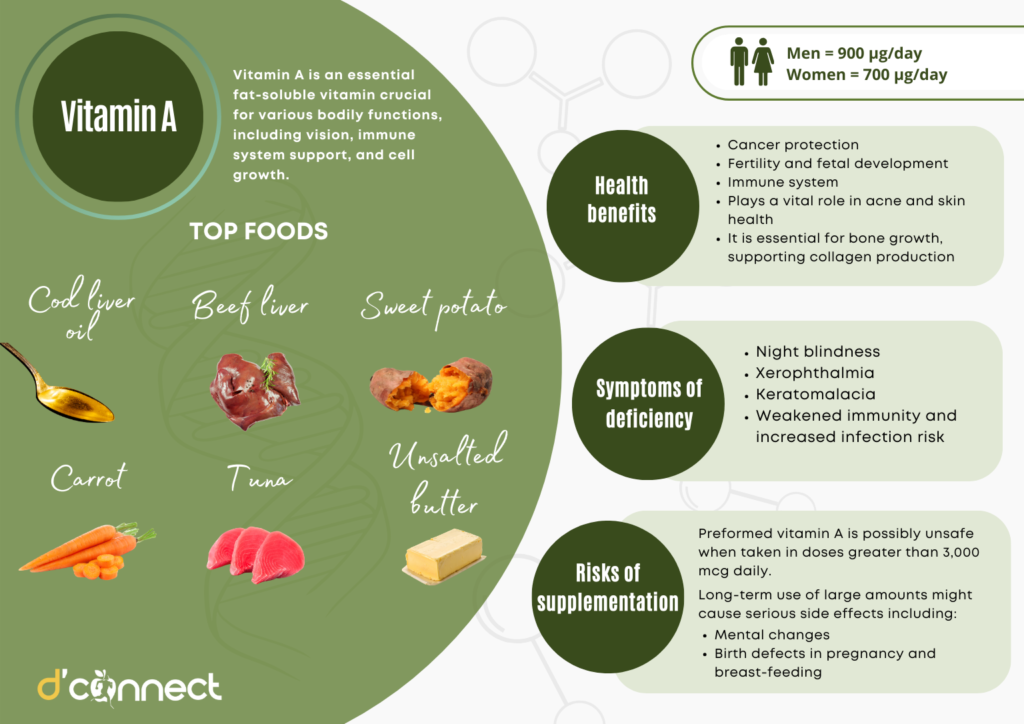

Vitamin A is an essential fat-soluble vitamin crucial for various bodily functions, including vision, immune system support, and cell growth. It exists in two main dietary forms:

- Preformed vitamin A (retinoids) – found in animal-based foods like liver, fish and eggs

- Pro-vitamin A (carotenoids) – found in plant-based foods such as carrots, spinach and sweet potatoes

The body converts pro-vitamin A into active forms of vitamin A as needed.

One of the most well-known roles of vitamin A is its contribution to eye health and vision. It forms part of rhodopsin, a pigment in the retina that allows the eyes to adapt to low-light conditions.

Vitamin A also maintains the health of the cornea and other eye tissues. Beyond vision, it strengthens the immune system by supporting white blood cell production and maintaining the integrity of mucous membranes, which act as barriers against infections.

Vitamin A is also vital for cell differentiation, a process where cells mature into specific types, such as skin or organ cells. This function is particularly important during periods of rapid growth, such as pregnancy and early childhood.[1]

History of Vitamin A

The discovery of vitamin A began in the early 20th century as scientists investigated the relationship between diet and health. In 1913, researchers Elmer McCollum and Marguerite Davis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison identified a “fat-soluble factor” in butterfat and egg yolk that was essential for the growth and survival of experimental animals.

Around the same time, Thomas Osborne and Lafayette Mendel at Yale University conducted similar experiments, confirming the existence of this unknown nutrient.

Vitamin A was first identified in butterfat and egg yolk

Prior to its discovery, diseases like night blindness and growth retardation were associated with poor diets, but the specific dietary component responsible remained unknown.

McCollum and Davis referred to this nutrient as “fat-soluble A”, distinguishing it from another dietary factor they had identified, which they called “water-soluble B” (later found to be the B vitamins).

The isolation and chemical characterisation of vitamin A came in subsequent decades. In 1931, Swiss chemist Paul Karrer determined its molecular structure and identified its active form, retinol, earning him a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1937.

The discovery paved the way for synthesising vitamin A, making it accessible for widespread use in addressing deficiencies, particularly in developing countries.

These breakthroughs underscored the vital role of diet in health and laid the foundation for modern nutritional science.[2]

Vitamin A deficiency

Vitamin A deficiency is still common in many developing countries, often as a result of limited access to foods containing preformed vitamin A from animal-based food sources and to foods containing provitamin A carotenoids because of poverty or traditional diets.

In 2013, The World Health Organization recognised vitamin A deficiency as a public health issue, impacting approximately one third of children aged 6 to 59 months, with the highest prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa (48%) and South Asia (44%).[3]

Vitamin A deficiency is common in many developing countries

Different types of Vitamin A

Vitamin A exists in several forms, broadly classified into preformed vitamin A (retinoids) and pro-vitamin A (carotenoids). These types differ in their sources, structure, and function.

Preformed Vitamin A (Retinoids) is found in animal-based foods and supplements, and these active forms can be used by the body immediately. Retinoids include:

- Retinol – the most common form found in animal-derived foods like liver and dairy, which can be converted into retinol or retinoic acid

- Retinal (retinaldehyde) – essential for vision as it forms rhodopsin, the pigment necessary for low-light and colour vision

- Retinoic acid – regulates gene expression and cell differentiation, but can’t be converted back to other forms

- Retinyl esters – serves as the storage form of vitamin A in the liver

Provitamin A (Carotenoids) is found in plant-based foods and serves as a precursor to active vitamin A, requiring conversion to retinol in the body. Common carotenoids include:

- Beta-carotene – the most efficient provitamin A, easily converted to retinol in the body

- Alpha-carotene and beta-cryptoxanthin – less efficient when it comes to conversion than beta-carotene

Synthetic forms of vitamin A are often used in supplements, fortified foods, and medical treatment. These are:

- Retinyl palmitate – common form in fortified animal, dairy and cosmetic products

- Tretinoin (all-trans retinoic acid) – used in topical and oral treatments for skin conditions like acne

- Isotretinoin – prescribed for severe acne

Health benefits

Eye health and prevent age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

Vitamin A plays a vital role in maintaining healthy vision and protecting the eyes from various conditions. It is essential for both the physiological processes of vision and the structural integrity of the eye.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of vision loss among older adults, primarily affecting the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed vision.

Vitamin A, particularly in its carotenoid forms like beta-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin, plays a significant role in reducing the risk of AMD and slowing its progression.

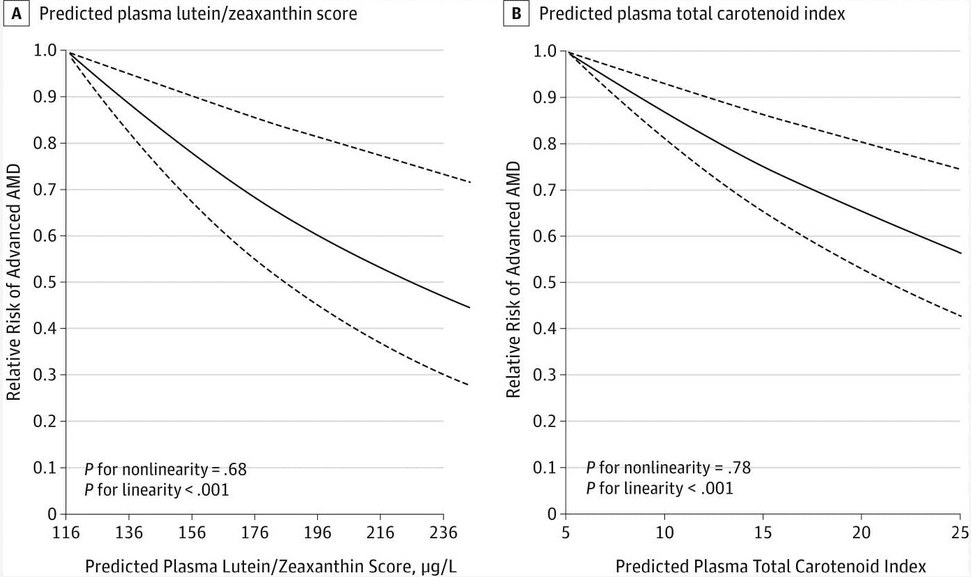

A study by Wu et al. were looking at the effect of carotenoids intake in people with AMD. The study found that a higher intake of lutein or zeaxanthin score was associated with about 40% reduced risk of advanced AMD in both men and women.

Other carotenoids, including beta-cryptoxanthin, alpha-carotene and beta-carotene, were linked to a 25-35% lower risk of advanced AMD.[4]

Another study by Pfau et al. observed the effect of retinol supplement in patients with AMD. They were given 16,000 IU (400 µg) of vitamin A palmitate daily for eight weeks. The study found a low-dose of vitamin A supplementation helped improve some functional changes in eyes with AMD.[5]

Cancer protection

Retinol and vitamin A derivatives influence cell differentiation proliferation, and apoptosis and play an important physiologic role in a wide range of biological processes.

Carotenoids may play a protective role in the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Studies showed that intakes of alpha-carotene and beta-carotene were associated with a significantly decreased risk of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, but not follicular lymphoma or small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[6]

A study by Lu et al. was looking at the association between specific carotenoid intake and colorectal cancer risk in Chinese adults. A strong link was found between higher beta-cryptoxanthin intake and a lower risk of colorectal cancer, with the highest intake reducing the risk by 77%.

Similar protective effects were seen for alpha-carotene (50% lower risk), beta-carotene (55% lower risk), and lycopene (49% lower risk).[7]

Vitamin A may have a protective role in the development of cancers

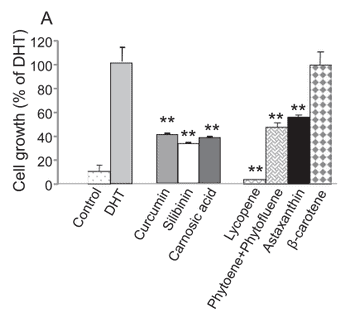

Furthermore, a study by Linnewiel-Hermoni et al. observed the anti-cancer effect of carotenoids in cancer cell activity. The study found that combining carotenoids (lycopene, phytoene, and phytofluene), carotenoids with polyphenols (carnosic acid and curcumin), or carotenoids with other compounds (like vitamin E) effectively reduce prostate cancer cell activity and boosts antioxidant responses.

In addition, these combinations showed a much stronger effect than the individual nutrients alone, highlighting their synergy.[8]

Fertility and fetal development

Vitamin A is essential for both male and female fertility and plays a critical role in the healthy development of a fetus during pregnancy.

Its functions in reproduction and fetal growth stem from its involvement in:

- cellular differentiation

- gene expression

- tissue development

A study by Chien et al. examined how maternal vitamin A deficiency affected fetal pancreas development. The study was conducted in mice by feeding the female mice with a diet lacking in vitamin A prior to mating as well as during pregnancy. The result found that the development of fetal pancreas was impaired, with 50-70% reduction in size of pancreata.[9]

Immune system

In populations where vitamin A availability from food is low, infectious diseases can precipitate vitamin A deficiency by decreasing intake, decreasing absorption, and increasing excretion.

Vitamin A deficiency impairs innate immunity by impeding normal regeneration of mucosal barriers damaged by infection, and by diminishing the function of neutrophils, macrophages, and natural killer cells.

A study by Vlasova et al. examined the impact of vitamin A deficiency (VAD) acquired before birth on immune responses and the effectiveness of rotavirus vaccine. Using a special pig model, the result showed weaker immune responses and more severe diarrhea in piglets with VAD compared to those with sufficient vitamin A levels.

This suggests that prenatal vitamin A deficiency can impair the body’s ability to fight infections and reduce the effectiveness of vaccines in newborns.[10]

Pre-natal vitamin A deficiency can impair newborns’ ability to fight infections

Another by Yang et al. examined the effects of vitamin A deficiency on mucosal immunity during intestinal infection using a rat model. Rats were divided into two groups, one receiving a vitamin A-free diet and the other receiving vitamin A supplementation. Salmonella infection was induced in half of the rats in each group to study immune responses.

The result showed that vitamin A deficiency weakens both humoral and cellular immunity in the gut, leading to impaired defense mechanisms against intestinal infections.[11]

Health claims

Acne and skin health

Vitamin A plays a vital role in skin health by promoting cell turnover, reducing inflammation, and regulating oil production, making it beneficial for acne treatment.

Retinoids, the active derivatives of vitamin A, can help to improve:

- skin texture

- fade hyperpigmentation

- enhance skin elasticity by boosting collagen synthesis and preventing its breakdown

Moreover, vitamin A has antioxidant properties that combat free radical damage, a key contributor to premature aging.

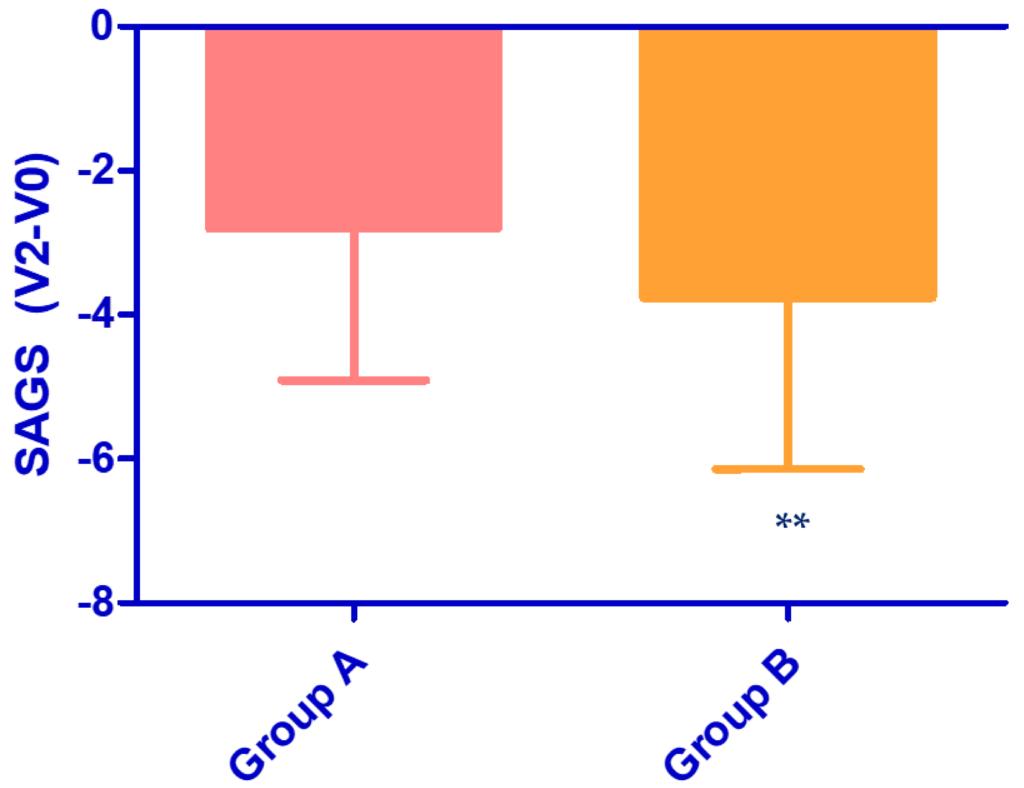

A 2023 study by Milani and Colombo investigated the anti-aging effects of combining oral vitamin A supplementation with topical retinoic acid treatment.

In these 12-week trials, participants with moderate to severe skin aging were divided into two groups: one received both oral vitamin A (50,000 IU daily) and a 0.02% retinoic acid gel applied nightly, while the other used only the topical gel. The combination therapy group showed superior clinical improvements in skin aging compared to the topical treatment alone.[12]

Skin Aging Global Score (SAGS) is based on the sum of different six parameters (elasticity, wrinkle, roughness, pigmentation, erythema, and skin pores.

Figure 5. Reduction in Skin Aging Global Score (SAGS) from baseline (V0) to 12 weeks (V2). Group A (topical treatment only) and Group B (oral vitamin A + topical treatments).[12]

Bone health

Vitamin A plays a crucial role in bone health, as both deficiency and excess can impact bone metabolism. It is essential for bone growth, development and remodeling by regulating osteoblast (bone-forming) and osteoclast (bone-resorbing) activity, supporting collagen production, and interacting with vitamin D for calcium metabolism.

A study by Jonge et al. investigated the relationship between vitamin A consumption and bone health among individuals aged 55 and older. The research found that higher dietary intake of total vitamin A and retinol was associated with increased bone mineral density (BMD) and a reduced risk of fractures, particularly in overweight individuals.

These findings suggest that elevated vitamin A intake may have a favourable impact on bone health in the elderly, especially among those who are overweight.[13]

Best sources of Vitamin A

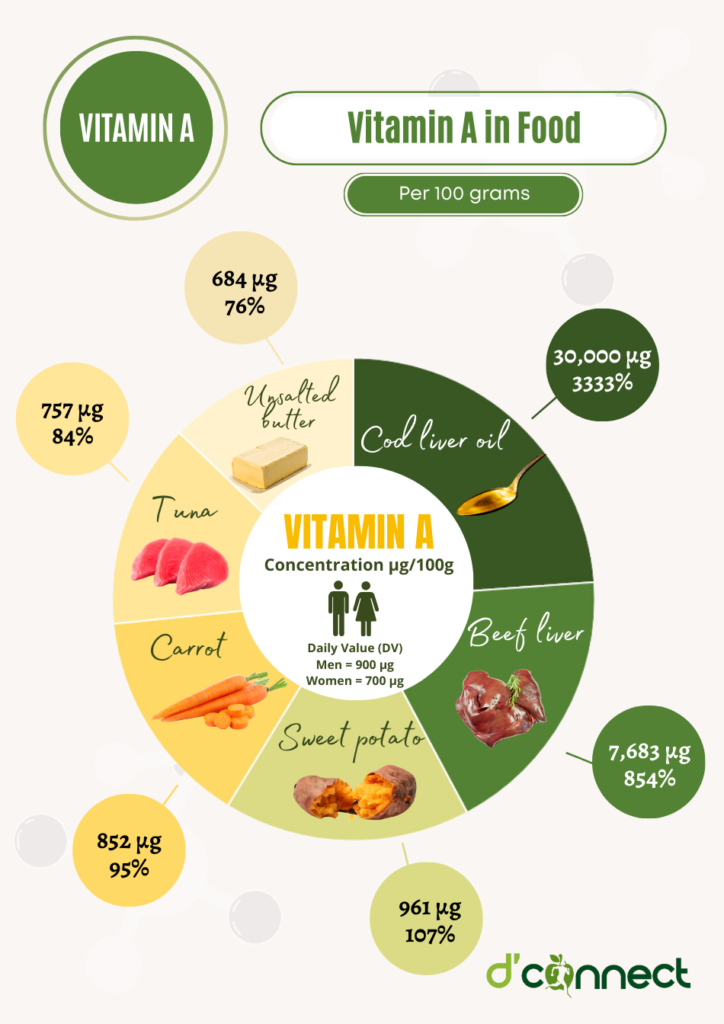

Vitamin A can be obtained from both animal-based (preformed vitamin A) and plant-based (pro-vitamin A carotenoids) sources.[14]

Food Sources | Concentration (µg/100g) | Daily Value (DV) |

Cod liver oil | 30,000 µg | 3333% |

Beef liver | 7,683 µg | 854% |

Sweet potato | 961 µg | 107% |

Carrot | 852 µg | 95% |

Tuna | 757 µg | 84% |

Unsalted butter | 684 µg | 76% |

Butternut squash | 558 µg | 62% |

Spinach | 524 µg | 58% |

Lettuce | 436 µg | 48% |

Egg yolk | 381 µg | 42% |

Rock melons | 169 µg | 19% |

Red bell pepper | 147 µg | 16% |

Broccoli | 77 µg | 9% |

Pink grapefruit | 58 µg | 6% |

Mango | 54 µg | 6% |

Aim to consume vitamin A from both animal and plant sources.

Daily requirements and recommended intake

The amount of vitamin A we need depends on age and sex. The amount of adequate intake of vitamin A is listed below in micrograms per day.[15]

Age | Male (AI) | Female (AI) |

0-6 months | 250 µg/day | 250 µg/day |

7-12 months | 430 µg/day | 250 µg/day |

1-3 years | 300 µg/day | 300 µg/day |

4-8 years | 400 µg/day | 400 µg/day |

9-13 years | 600 µg/day | 600 µg/day |

14-18 years | 900 µg/day | 700 µg/day |

19-30 years | 900 µg/day | 700 µg/day |

31-50 years | 900 µg/day | 700 µg/day |

51-70 years | 900 µg/day | 700 µg/day |

>70 years | 900 µg/day | 700 µg/day |

Pregnancy (14-28 years) |

| 700 µg/day |

Pregnancy (19-50 years) |

| 800 µg/day |

Breastfeeding (all ages) |

| 1,100 µg/day |

AI = Adequate Intake.

How to take Vitamin A as a supplement

When taking vitamin A supplements, it’s best to do so with a meal containing healthy fats to enhance absorption, as vitamin A is fat-soluble.

The recommended daily dosage varies by age, sex and health status, but it’s important not to exceed the tolerable upper intake level to avoid toxicity.

Always follow the dosage instructions on the label or as advised by a healthcare provider to ensure safe and effective use.

Common signs and symptoms of Vitamin A deficiency

Eye health and vision

Vitamin A plays a crucial role in maintaining healthy vision. Deficiency often leads to the following health problems.

Night blindness

Difficulty seeing in low-light or dark environments due to impaired rhodopsin production in the retina.

Xerophthalmia

Xerophthalmia is a serious eye condition caused by a deficiency of vitamin A, which is essential for maintaining proper vision and eye health. It begins with dryness of the conjunctiva and cornea due to inadequate tear production, leading to discomfort and an increased risk of infection.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that about 254 million children have vitamin A deficiency and 2.8 million children have xerophthalmia. It is the most common cause of childhood blindness with 350,000 new cases every year.[16]

A characteristic sign of xerophthalmia is the presence of Bitot’s spots — white, foamy, keratinised patches on the conjunctiva that indicate advanced vitamin A deficiency.

If left untreated, the condition can progress to corneal ulceration and softening, ultimately leading to permanent blindness.

Keratomalacia

Keratomalacia is a severe eye disorder caused by a deficiency of vitamin A, which is essential for maintaining the health of the cornea and conjunctiva. It is characterised by the progressive softening and thinning of the cornea, leading to ulceration, scarring, and if left untreated, eventual blindness.

Weakened immunity and increased infection risk

Vitamin A supports the immune system by maintaining mucosal barriers and aiding white blood cell function.[17]

Deficiency can cause:

- Frequent respiratory infections (e.g., pneumonia)

- Increased susceptibility to gastrointestinal infections (e.g., diarrhea)

- Higher risk of severe illness from diseases like measles

A study examined the impact of vitamin A deficiency (VAD) on immune responses during persistent lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection in mice. VAD mice showed extreme inflammation and more severe liver pathology, with high deaths during persistent infection.[18]

Skin and hair problems

Vitamin A is essential for healthy epithelial cells.[19] Its deficiency can result in:

- Dry and rough skin

- Brittle or dry hair

- Hair loses its shine and elasticity

Reproductive health problems

Vitamin A plays a crucial role in reproductive health for both men and women, and its deficiency can lead to serious complications. In men, inadequate vitamin A levels can impair sperm production and quality, potentially leading to infertility.

Inadequate vitamin A levels can impair fertility

In women, vitamin A is essential for normal ovarian function, fetal development, and maintaining a healthy pregnancy.

In severe cases, deficiency has been linked to an increased risk of:

- infertility

- irregular menstrual cycles

- complications during pregnancy

such as preterm birth, fetal growth restrictions, and congenital abnormalities.

Growth and development issues

Vitamin A deficiency can lead to significant growth and development issues in children, including:

- stunted growth

- delayed bone development

- impaired overall body growth

primarily due to its role in proper cell differentiation and proliferation necessary for healthy development throughout the body.

A study explored the link between vitamin A deficiency (VAD) and childhood stunting, wasting, and underweight in Uganda. The study found that VAD is associated with increased risks of stunting, underweight, and wasting in Ugandan children.

The analysis of data from over 4,700 children revealed that VAD was a significant factor in these growth deficiencies.[20]

Vitamin A risks and side effects

Preformed vitamin A is possibly unsafe when taken in doses greater than 3,000 mcg daily. Higher doses might increase the risk of side effects.

Long-term use of large amounts might cause serious side effects including mental changes. Furthermore, larger amounts are also possibly unsafe and can cause birth defects in pregnancy and breast-feeding.

Possible interactions with herbs and supplements

Vitamin A can interact with some herbs and supplements, affecting their absorption or increasing the risk of side effects. For example, taking high doses of vitamin A with other fat-soluble vitamins including:

can cause an imbalance as they share similar absorption pathways.

Possible interactions with medication

Vitamin A may interact with certain medications. It can also affect the absorption of other fat-soluble vitamins and medications. Below are a few interactions between vitamin A and medications.

- Orlistat (Alli, Xenical) – a weight loss drug that can decrease the absorption of vitamin A

- Acitretin (Soriatane) – is used to treat psoriasis. It is an oral retinoid, and if used in conjunction with vitamin A supplementation, it can dangerously high levels of vitamin A in the blood

- Bexarotene (Targetin) – is used to treat the skin effects of T-cell lymphoma. It is also based on retinoid formulation and has the same risks as Acitretin.

Summary

Key Takeaway — In this illustration we have outlined the most important information that you should know about vitamin A.

Related Questions

1. Can I take vitamin A instead of Accutane?

Both Accutane and Vitamin A are effective acne treatments with similar mechanisms, but Accutane is typically stronger and recommended for persistent cases.

Recent studies indicate that high-dose Vitamin A may offer a viable alternative in some situations.

2. What foods block the absorption of vitamin A?

The fiber in fruits and vegetables can reduce the bioavailability of carotenoids.

3. Does taking too much vitamin D deplete levels of vitamin A?Excessive vitamin D intake can potentially impact vitamin A levels by altering vitamin A metabolism.

High vitamin D levels might increase the demand for vitamin A to maintain a proper balance, potentially leading to depletion.

If you would like to read more about different vitamins and minerals, please see our Nutrients section.

Bernadeth’s passion in cooking, food and health led her to learn more about nutrition and the importance of functional foods. As a nutritionist, Bernadeth’s goal is to encourage a healthy-balanced diet and share the evidence-based nutrition knowledge in order for people to live healthier and longer lives…

If you would like to learn more about Bernadeth, see Expert: Bernadeth Atrinindarti.

Reference

(1) Carazo, A., Macáková, K., Matoušová, K., Krčmová, L. K., Protti, M., & Mladěnka, P. (2021). Vitamin A Update: Forms, Sources, Kinetics, Detection, Function, Deficiency, Therapeutic Use and Toxicity. Nutrients, 13(5), 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051703

(2) Lerner U. H. (2024). Vitamin A – discovery, metabolism, receptor signaling and effects on bone mass and fracture susceptibility. Frontiers in endocrinology, 15, 1298851. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1298851

(3) UNICEF. (2023). Vitamin A. Nutrition. Retrieved from https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/vitamin-a-deficiency/

(4) Wu, J., Cho, E., Willett, W. C., Sastry, S. M., & Schaumberg, D. A. (2015). Intakes of Lutein, Zeaxanthin, and Other Carotenoids and Age-Related Macular Degeneration During 2 Decades of Prospective Follow-up. JAMA ophthalmology, 133(12), 1415–1424. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.3590

(5) Pfau, K., Jeffrey, B. G., & Cukras, C. A. (2023). LOW-DOSE SUPPLEMENTATION WITH RETINOL IMPROVES RETINAL FUNCTION IN EYES WITH AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION BUT WITHOUT RETICULAR PSEUDODRUSEN. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.), 43(9), 1462–1471.

(6) Chen, F., Hu, J., Liu, P., Li, J., Wei, Z., & Liu, P. (2017). Carotenoid intake and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Annals of hematology, 96(6), 957–965.

(7) Lu, M.-S., Fang, Y.-J., Chen, Y.-M., Luo, W.-P., Pan, Z.-Z., Zhong, X., & Zhang, C.-X. (2015). Higher intake of carotenoid is associated with a lower risk of colorectal cancer in Chinese adults: a case–control study. European Journal of Nutrition, 54(4), 619-628. doi:10.1007/s00394-014-0743-7

(8) Linnewiel-Hermoni, K., Khanin, M., Danilenko, M., Zango, G., Amosi, Y., Levy, J., & Sharoni, Y. (2015). The anti-cancer effects of carotenoids and other phytonutrients resides in their combined activity. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 572, 28-35.

(9) Chien, C.-Y., Lee, H.-S., Cho, C. H.-H., Lin, K.-I., Tosh, D., Wu, R.-R., . . . Shen, C.-N. (2016). Maternal vitamin A deficiency during pregnancy affects vascularised islet development. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 36, 51-59.

(10) Vlasova, A. N., Chattha, K. S., Kandasamy, S., Siegismund, C. S., & Saif, L. J. (2013). Prenatally acquired vitamin A deficiency alters innate immune responses to human rotavirus in a gnotobiotic pig model. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), 190(9), 4742–4753. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1203575

(11) Yang, Y., Yuan, Y., Tao, Y., & Wang, W. (2011). Effects of vitamin A deficiency on mucosal immunity and response to intestinal infection in rats. Nutrition, 27(2), 227-232.

(12) Milani, M., & Colombo, F., on behalf of the To-Re Trial Study Group. (2023). Skin Anti-Aging Effect of Oral Vitamin A Supplementation in Combination with Topical Retinoic Acid Treatment in Comparison with Topical Treatment Alone: A Randomised, Prospective, Assessor-Blinded, Parallel Trial. Cosmetics, 10(5), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics10050144

(13) de Jonge, E. A. L., Kiefte-de Jong, J. C., Campos-Obando, N., Booij, L., Franco, O. H., Hofman, A., . . . Zillikens, M. C. (2015). Dietary vitamin A intake and bone health in the elderly: the Rotterdam Study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69(12), 1360-1368.

(14) DipION, D. W. B. H. M. (2024, November 10, 2024). Top 10 Foods High in Vitamin A. Retrieved from https://www.myfooddata.com/articles/food-sources-of-vitamin-A.php

(15) Vitamin A. (2005). Nutrient Reference Value for Australia and New Zealand. Retrieved from https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/nutrient-reference-values/nutrients/vitamin-a

(16) Feroze KB, Kaufman EJ. Xerophthalmia. [Updated 2023 Apr 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431094/

(17) Health, N. I. o. (2022). Vitamin A and Carotenoids. Retrieved from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminA-Consumer/

(18) Liang, Y., Yi, P., Wang, X., Zhang, B., Jie, Z., Soong, L., & Sun, J. (2020). Retinoic Acid Modulates Hyperactive T Cell Responses and Protects Vitamin A-Deficient Mice against Persistent Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Infection. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), 204(11), 2984–2994. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1901091

(19) Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Vitamin A Deficiency. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23107-vitamin-a-deficiency

(20) Ssentongo, P., Ba, D. M., Ssentongo, A. E., Fronterre, C., Whalen, A., Yang, Y., Ericson, J. E., & Chinchilli, V. M. (2020). Association of vitamin A deficiency with early childhood stunting in Uganda: A population-based cross-sectional study. PloS one, 15(5), e0233615. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233615