Hannah King

BSc (Human Nutrition)

Jump to:

- What is Vitamin B12?

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Different types of Vitamin B12

- Health Benefits

- Health Claims

- Best sources of Vitamin B12

- Daily requirements and intake

- How to take Vitamin B12

- Signs and symptoms of deficiency

- Risk and side effects

- Interactions - herbs and supplements

- Interactions – medication

- Summary

- Related Questions

Vitamin B12, a water soluble vitamin, is known for its essential role in red blood cell formation, the production of DNA, and nerve function.

Many people are aware that vitamin B12 is often deficient in specific populations, particularly vegetarians and vegans, due to its predominance in animal-based foods.

Given that vitamin B12 is an essential nutrient, the first question that usually comes to mind is what are the consequences of a vitamin B12 deficiency? This and more is discussed in the article.

What is Vitamin B12?

Vitamin B12 is a vital nutrient that plays a key role in:

- production of red blood cells

- supporting the nervous system

- synthesising DNA

It is absorbed in the body by being detached from proteins in food, then combining with a protein called intrinsic factor in the stomach, which helps absorption in the intestine.[1]

History of Vitamin B12

In the 1920s vitamin B12 was first identified as a vital nutrient, known as the extrinsic factor, by researchers Minot, Murphy, and Whipple. They found this by adding liver to the diet, which in turn alleviated the symptoms of pernicious anaemia.

Eventually, the nutrient was isolated from liver samples by adding cyanide and using an organic solvent, which allowed it to be crystallised and developing a deep-red pigment.

Dorothy Hodgkin then used x-ray crystallography to determine the compound’s structure, to which it was named cyanocobalamin.[2]

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Since the discovery of vitamin B12, much has been learned about its deficiency, particularly concerning pernicious anaemia. It’s often caused by dietary inadequacy, especially among children and women of reproductive age.[3]

Pernicious anaemia is characterised by a decrease in red blood cells and can be fatal. It results from autoimmune destruction of gastric parietal cells and intrinsic factors, essential for B12 absorption.[4]

Additionally, vitamin B12 and folate are essential for the methionine synthase reaction, crucial for DNA replication and repair. Deficiency in either disrupts this process.[5]

Vitamin B12 is crucial for DNA replication

Vitamin B12 converts methyl malonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, aiding energy production and heme synthesis. Deficiency leads to substrate accumulation, increasing methylmalonic acid and homocysteine levels, causing megaloblastic anaemia and neurological symptoms.[6]

Who is most at risk of Vitamin B12 deficiency?

Autoimmune conditions

One key group of people at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency is those with pernicious anaemia. This autoimmune condition is characterised by the body’s immune system attacking gastric parietal cells, which are responsible for producing intrinsic factors.

Intrinsic factor is a protein required for vitamin B12 absorption in the small intestine. Without enough intrinsic factor, even if someone has sufficient vitamin B12 in their diet, they cannot absorb it effectively. This leads to a deficiency.[7]

Seniors and elderly

Another group that is at risk of vitamin B12 deficiency is the elderly, particularly those over the age of 60, where deficiency prevalence increases significantly.

In some cases, the deficiency is linked to pernicious anaemia, but it may also be related to changes in digestion and absorption that occur with age.[4]

Infants and teenagers

Younger populations, such as infants, children, adolescents, and women of reproductive age, are also at higher risk, particularly where access to animal-derived foods is limited or a vegan diet is adopted.

Inadequate intake, bioavailability issues, and malabsorption are common causes of B12 deficiency in these groups.

However, conditions or events such as gastrointestinal surgery, infections, and certain medications can also disrupt B12 absorption and transport within the body, leading to deficiency.[4]

Individuals following a vegan diet

Vitamin B12 is absent in unfortified plant-based foods, meaning there is a significant risk of deficiency in vegan and vegetarian populations. This risk is particularly concerning for women of childbearing age and during pregnancy, where B12 deficiency is linked to neuro, vascular, immune, and inflammatory disorders.

RELATED — Health Risks of Long-Term Vegan and Vegetarian Diet (Part 1)

Plant-based diets are popular for ethical and environmental reasons, but ensuring proper nutrition is essential. Key tips include having B12 supplements, fortified foods, and seeking professional guidance, especially during dietary transitions or pregnancy.[8]

Fortified B12 sources in New Zealand include ‘So Good’ plant milk, Marmite, and Bragg Nutritional Yeast.

Different types of Vitamin B12

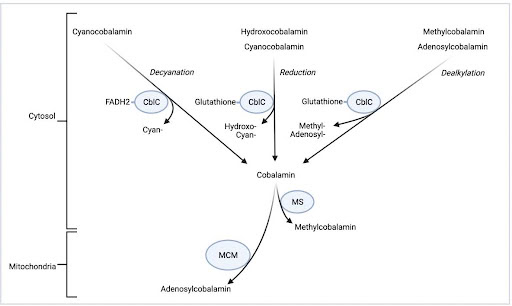

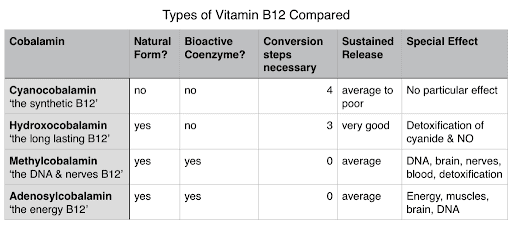

Vitamin B12 comes in four main forms, which are cyanocobalamin, methylcobalamin, hydroxocobalamin and adenosylcobalamin.

Cobalamin is then either reassembled as methylcobalamin by methionine synthase (MS) for use in the cytosol or as adenosylcobalamin by methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (MM) for use in the mitochondria.

Cyanocobalamin is a synthetic form of vitamin B12, not found in nature, but widely used in supplements because of its stability and cost-effectiveness.[9]

When ingested, cyanocobalamin is converted into the active forms of B12, methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin, which are necessary for vital functions like DNA synthesis and nerve maintenance.

Cyanocobalamin contains a cyanide molecule attached to the cobalt ion at its core, which is removed during conversion.[10]

Methylcobalamin is a naturally occurring form of vitamin B12 found in food sources and supplements. It already exists in its active form, making it immediately usable by the body. Unlike cyanocobalamin, methylcobalamin has a methyl group attached to the cobalt ion, which is crucial for processes like nerve function and DNA replication.

Hydroxocobalamin is another naturally occurring form, commonly used in injections to treat B12 deficiency, especially in cases of malabsorption or pernicious anaemia.

It is a precursor (a substance that converts into a more active form) to the active forms of B12 and is known for its longer-lasting effects in the body compared to other forms, as well as its effectiveness in treating conditions like cyanide poisoning.[11]

Adenosylcobalamin is a natural, bioactive form of vitamin B12, commonly found in food and the body’s organs. It makes up about 20% of B12 in the blood and works alongside methylcobalamin as one of the two forms the body can directly use.[12]

In the table above it is easy to conclude for what type of vitamin B12 we should be aiming for.[13]

Health benefits of Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 serves as a cofactor for enzymes like methionine synthase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, which are essential in various cellular processes.

These enzymes aid in DNA methylation, a process where methyl groups are added to DNA molecules, influencing gene activation and thus impacting cell function and growth.

Vitamin B12 also plays a role in nucleotide synthesis, vital for DNA replication and transcription, as nucleotides are the building blocks of DNA.[14]

Overall, the functions of vitamin B12 contribute to growth, cell development, and the metabolism of fats and carbohydrates.[15]

Supporting Red Blood Cell Formation

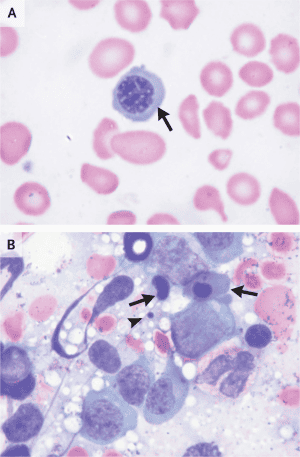

Vitamin B12 is essential for the production of red blood cells. Low B12 levels can lead to a reduction in red blood cell formation, causing them to develop improperly.

This can result in megaloblastic anaemia, where red blood cells are larger and unable to move from the bone marrow into the bloodstream efficiently, leading to symptoms such as fatigue and weakness.[1]

Vitamin B12 is essential for the production of red blood cells

Image B presents a bone marrow sample with immature red blood cell precursors, indicating disrupted normal cell development, characteristic of megaloblastic anaemia caused by vitamin B12 deficiency.

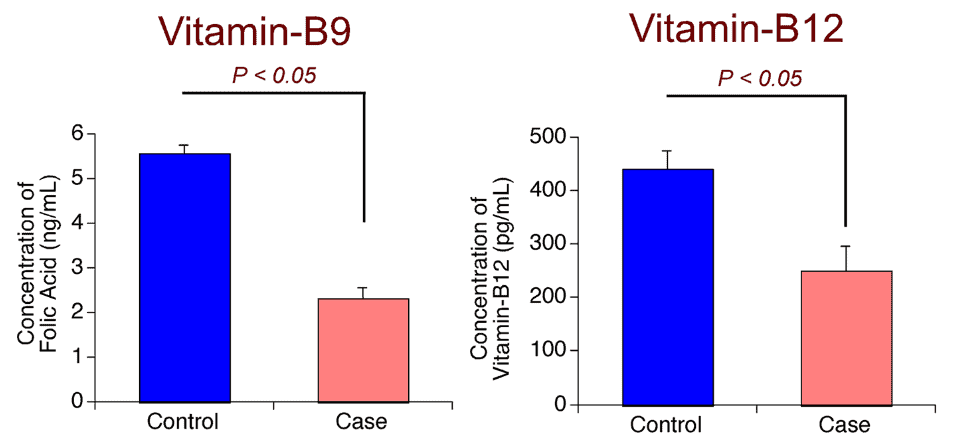

One study found that people with megaloblastic anaemia have about half the levels of vitamins B9 and B12 in their blood compared to healthy individuals, as shown by comparing affected cases with controls.[16,17]

Maintaining Healthy Nerve and Brain Function

Low vitamin B12 concentrations are associated with poorer memory performance, partly due to reduced microstructural integrity of the hippocampus – the part of your brain that’s responsible for your memory and learning.[1]

RELATED — Diet for a Healthy Brain

Observational studies have shown a link between elevated homocysteine levels and the incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia, suggesting that B12’s role in lowering homocysteine may help protect cognitive function.[19]

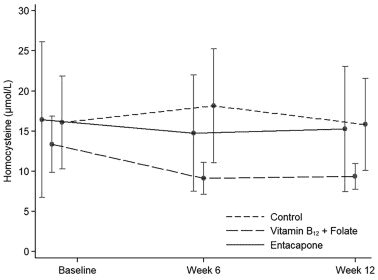

One study found vitamin B12 and folate supplementation significantly lowered homocysteine levels in levodopa-treated Parkison’s Disease patients.[20]

Preventing Birth Complications

Vitamin B12 plays an important role in preventing neural tube defects (NTDs), which is a condition seen when normal neural tube closure fails to occur in babies.

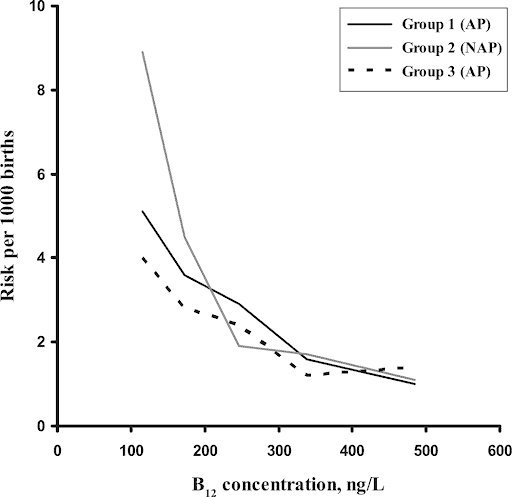

Research shows that mothers with low vitamin B12 levels are more likely to have infants affected by NTDs. One study found that mothers in the lowest B12 quartiles had a two to three times higher risk of having a child with a neural tube defect, particularly when their blood B12 concentrations during pregnancy were below 250 ng/L.[1]

It was assessed based on her vitamin B12 status during an affected pregnancy (AP) or a non-affected pregnancy (NAP). As B12 concentrations increase, the risk of NTD decreases.

While folic acid has been the primary focus in preventing NTDs, emerging evidence highlights the importance of adequate vitamin B12 levels for reducing the risk of these birth complications.[22]

Health claims that still need more evidence and research

While low B12 levels have been linked to memory problems and dementia, studies have not conclusively shown that B12 supplementation benefits individuals with these conditions.

Additionally, the relationship between B12 levels and cancer remains unclear, with studies showing both high and low levels linked to cancer risk.

Further investigation is needed to understand B12’s role in heart disease, infertility, age-related macular degeneration, eczema, and weight loss.[23]

Best sources of Vitamin B12

Food Item | Concentration (µg/100g) |

Cockles (raw) | 47.0 |

Chicken liver (raw) | 24.0 |

Oysters (raw) | 17.0 |

Paua (raw) | 8.0 |

Trout (raw) | 7.8 |

Mussel (raw) | 7.3 |

Edam Cheese | 7.2 |

Kahawai (raw) | 6.3 |

Canned Tuna in Spring water | 4.7 |

Venison Loin Chop (raw) | 4.0 |

Duck (raw) | 3.0 |

Beef Hindquarter Silverside (raw) | 2.9 |

Lamb, forequarter round neck chops (raw) | 2.9 |

Chicken egg (boiled) | 2.4 |

A2 Milk | 0.5 |

Fortified foods, particularly breakfast cereals, often contribute significantly to the daily intake of vitamin B12 food.[25,26,27]

Daily requirements and recommended intake

The recommended daily intake of vitamin B12 varies by age and life stage, as follows:

Age group | Recommended intake (mcg) |

Birth to 6 months | 0.4 |

Infants 7-12 months | 0.5 |

Children 1-3 years | 0.9 |

Children 4-8 years | 1.2 |

Children 9-13 years | 1.8 |

Teens 14-18 years | 2.4 |

Adults | 2.4 |

Pregnant teens and women | 2.6 |

Breastfeeding teens and women | 2.8 |

The daily requirements above are from the NIH and they are the same values as found in Nutrient Reference Values (NRV) for Australia and New Zealand as well as the Ministry of Health.[1]

How to take Vitamin B12 as a supplement

Vitamin B12 supplements come in various forms, including multivitamin/mineral supplements, B-complex vitamins, and standalone B12 products.

Multivitamins typically provide 5 to 25mcg of B12, while B-complex supplements offer higher doses of 50 to 500mcg. Standalone B12 supplements can range from 500 to 1,000mcg.

Cyanocobalamin is the most commonly used form in supplements

Absorption rates remain consistent across forms, which is about 50% being absorbed at doses under 1–2mcg, correlating with the intrinsic factor’s capacity.

Higher doses result in significantly lower absorption. Sublingual forms, like tablets or lozenges, show no significant difference in effectiveness compared to oral preparations.[1]

Common signs and symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency

Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to a range of serious health effects, so it is important to be able to identify any signs and symptoms early.

One of the key indications of B12 deficiency is megaloblastic anaemia, where red blood cells become abnormally large and immature. This condition can also result in reduced counts of white and red blood cells, low platelet levels, and glossitis (inflammation of the tongue).

Other common symptoms include:

- fatigue

- palpitations

- pale skin

- weight loss

- infertility

- dementia

In some cases, neurological changes such as numbness and tingling in the hands and feet occur, even in the absence of anaemia, making early diagnosis critical to prevent irreversible nerve damage.

For pregnant and breastfeeding women, a vitamin B12 deficiency poses added risks, such as:

- neural tube defects

- developmental delays

- failure to thrive

- anaemia in newborns

It is important that women at high risk of B12 deficiency supplement in order to avoid these complications.[28]

Vitamin B12 risk and side effects

There is no established Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for vitamin B12, as no adverse effects have been found in healthy individuals consuming excess B12 from food or supplements. However, it is usually recommended for adults to remain at 2.4mcg level of intake.

Although some animal studies have shown a potential link between B12 intake and cancer, human research has shown the opposite, with increased B12 actually inhibiting certain cancers.

Rare cases of acne have been seen with B12 injections, but these were linked to specific formulations not commonly used today.

Overall, the evidence does not support setting an upper intake level for B12, and high doses used to treat conditions like pernicious anaemia are considered safe.

However, one special exception is for individuals with Leber’s optic atrophy, a condition characterised by vision loss.[29]

These individuals should avoid cyanocobalamin, the common form of B12, as it may increase the risk of nerve damage. Hydroxocobalamin is recommended instead.[30]

Possible interactions with herbs and supplements

When considering possible interactions between vitamin B12 and herbs or supplements, we should keep in mind the following.

Folic Acid

Supplementing with folic acid can mask symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment.

RELATED — Vitamin B9 (Folate)

Vitamin C and Potassium Supplements

Taking vitamin C and potassium around the same time as vitamin B12, could result in decreased absorption of vitamin B12 from the gastrointestinal tract.[31]

RELATED — Vitamin C (Immunity and Collagen booster)

If we are aiming to get most of our nutrients from the diet, it is unlikely that we will be consuming fruit at the same time as meat. Similar can be said about potassium, however, potassium can also be found in potatoes, beans and some vegetables.

Possible interactions with medication

Vitamin B12 needs an acidic environment for absorption in the terminal ileum. Therefore, medications that lower gastric pH, like antacids, can reduce the absorption of vitamin B12.[31]

Additionally, some drugs, such as gastric acid inhibitors and metformin, can interfere with vitamin B12 absorption and decrease the body’s overall levels of this vitamin.

People who take these medications long-term should consult their healthcare providers to monitor their vitamin B12 levels and ensure they are getting enough of this essential nutrient.[28]

Summary

Key Takeaway — In this illustration we have outlined the most important information that you should know about vitamin B12.

Related Questions

1. Can a plant-based diet provide enough vitamin B12 naturally?

No, a plant-based diet cannot provide sufficient vitamin B12 naturally, as B12 is primarily found in animal-based foods.

Vegans and vegetarians are at higher risk of deficiency unless they consume a decent amount of fortified foods (e.g., fortified plant milks, cereals) or take B12 supplements.

2. “How quickly do you feel better after vitamin B12 injections?“

Hydroxocobalamin (a common form of vitamin B12 injections) will begin to take effect on the body immediately.

But, it may take a few days or even weeks before any deficiency symptoms such as extreme tiredness or lack of energy start to improve.[32]

3. How long does it take to raise vitamin B12 levels through diet alone?

It could take anywhere between several weeks to a few months.

Raising vitamin B12 levels through diet alone varies based on an individual’s baseline levels, dietary habits, and overall health.

Eating important sources like animal products as well as fortified foods will be crucial. However, since the body absorbs only a limited amount of B12 at a time, having regular but moderate consumption of these foods is important.

References

(1) Vitamin B12 Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. (2024). National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB12-HealthProfessional/

(2) Smith, A. D., Warren, M. J., & Refsum, H. (2018). Vitamin B12. Advances in food and nutrition research, 83, 215-279.

(3) Herbert, V., & Zalusky, R. (1962). Interrelations of vitamin B 12 and folic acid metabolism: folic acid clearance studies. The Journal of clinical investigation, 41(6), 1263-1276.

(4) Green, R., Allen, L. H., Bjørke-Monsen, A.-L., Brito, A., Guéant, J.-L., Miller, J. W., Molloy, A. M., Nexo, E., Stabler, S., & Toh, B.-H. (2017). Vitamin B12 deficiency. Nature reviews Disease primers, 3(1), 1-20

(5) Miller, J. W., Garrod, M. G., Allen, L. H., Haan, M. N., & Green, R. (2009). Metabolic evidence of vitamin B12 deficiency, including high homocysteine and methylmalonic acid and low holotranscobalamin, is more pronounced in older adults with elevated plasma folate. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 90(6), 1586-1592.

(6) Selhub, J., Morris, M. S., & Jacques, P. F. (2007). In vitamin B12 deficiency, higher serum folate is associated with increased total homocysteine and methylmalonic acid concentrations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(50), 19995-20000.

(7) Robert, C., & Brown, D. L. (2003). Vitamin B12 deficiency. American family physician, 67(5), 979-986.

(8) Niklewicz, A., Smith, A. D., Smith, A., Holzer, A., Klein, A., McCaddon, A., Molloy, A. M., Wolffenbuttel, B. H. R., Nexo, E., McNulty, H., Refsum, H., Gueant, J. L., Dib, M. J., Ward, M., Murphy, M., Green, R., Ahmadi, K. R., Hannibal, L., Warren, M. J., & Owen, P. J. (2023). The importance of vitamin B12 for individuals choosing plant-based diets. Eur J Nutr, 62(3), 1551-1559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-022-03025-4

(9) Elgar, K. (n.d.). Vitamin B12: A Review of Clinical Use and Efficacy. Retrieved October 21, 2024, from https://www.nmi.health/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/NMJ_Vitamin-B12_A-Review-of-Clinical-Use-and-Efficacy.pdf

(10) Ajmera, R. (2023). Methylcobalamin vs. Cyanocobalamin: What’s the Difference? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/methylcobalamin-vs-cyanocobalamin

(11) Ahangar, E. R., & Pavan Annamaraju. (2023). Hydroxocobalamin. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557632/#:~:text=Hydroxocobalamin%20is%20a%20form%20of,associated%20with%20vitamin%20B12%20deficiency

(12) Adenosylcobalamin. (2024). B12-Vitamin.com. https://www.b12-vitamin.com/adenosylcobalamin/

(13) Vitamin B12 Forms. (2015). B12-Vitamin.com. https://www.b12-vitamin.com/forms/

(14) Halczuk, K., Kaźmierczak-Barańska, J., Karwowski, B. T., Karmańska, A., & Cieślak, M. (2023). Vitamin B12-Multifaceted In Vivo Functions and In Vitro Applications. Nutrients, 15(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122734

(15) Kumar, S. S., Chouhan, R. S., & Thakur, M. S. (2010). Trends in analysis of vitamin B12. Analytical biochemistry, 398(2), 139-149.

(16) Stabler, S. P. (2013). The New England Journal of Medicine, 368 (2), 149-160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1113996.

(17) Yadav, M. K., Manoli, N. M., & Madhunapantula, S. V. (2016). Comparative Assessment of vitamin B12, Folic Acid and Homocysteine Levels in Relation to p53 Expression in Megaloblastic Anaemia. PLoS ONE, 11(10), e0164559–e0164559. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164559

(18) Smith, A. D. (2016). Hippocampus as a mediator of the role of vitamin B12 in memory. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 103(4), 959-960.

(19) Ho, R. C., Cheung, M. W., Fu, E., Win, H. H., Zaw, M. H., Ng, A., & Mak, A. (2011). Is high homocysteine level a risk factor for cognitive decline in elderly? A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(7), 607-617

(20) Chumpol Anamnart, & Ram Kitjarak. (2021). Effects of vitamin B12, folate, and entacapone on homocysteine levels in levodopa-treated Parkinson’s disease patients: A randomised controlled study. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 88, 226–231.

(21) Molloy, A. M., Kirke, P. N., Troendle, J. F., Burke, H., Sutton, M., Brody, L. C., Scott, J. M., & Mills, J. L. (2009). Maternal vitamin B12 status and risk of neural tube defects in a population with high neural tube defect prevalence and no folic Acid fortification. Pediatrics, 123(3), 917-923. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1173

(22) Wahbeh, F., & Manyama, M. (2021). The role of vitamin B12 and genetic risk factors in the aetiology of neural tube defects: A systematic review. Int J Dev Neurosci, 81(5), 386-406.

(23) Gardner, A. (2023). Truth and Myths About B12. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/diet/features/b12-truths-myths

(24) New Zealand Food Composition Database. (2024). Vitamin B12. Retrieved from https://www.foodcomposition.co.nz/search/nutrient?code=VITB12

(25) Winkels, R. M., Brouwer, I. A., Clarke, R., Katan, M. B., & Verhoef, P. (2008). Bread co-fortified with folic acid and vitamin B12 improves the folate and vitamin B12 status of healthy older people: a randomised controlled trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 88(2), 348-355.

(26) Food Standards Australia New Zealand. (2021). Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code – Standard 1.3.2 – Vitamins and Minerals. https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2015L00400/latest/text

(27) Allen, L. H. (2012). Vitamin B-12. Advances in Nutrition, 3(1), 54-55.

(28) Langan, R. C., & Goodbred, A. J. (2017). Vitamin B12 deficiency: recognition and management. American family physician, 96(6), 384-389.

(29) Cleveland Clinic. (2024). Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/leber-hereditary-optic-neuropathy-lhon

(30) Nutrients, S. o. U. R. L. o., Intakes, S. C. o. t. S. E. o. D. R., Folate, i. P. o., Vitamins, O. B., & Choline. (2000). Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline.

(31) Carter, C., Boyd, M., & Nelson, M. (n.d.). Drug Interactions With Dietary Supplements. https://www.ncpa.co/issues/APMAY12-CE.pdf

(32) NHS website. (2022, October). Common questions about hydroxocobalamin. Nhs.uk. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/hydroxocobalamin/common-questions-about-hydroxocobalamin/#:~:text=When%20will%20I%20feel%20better,of%20energy