Bernadeth Atrinindarti

MAppSc (Advanced Nutrition Practice)

Jump to:

- What is Vitamin B3?

- Vitamin B3 deficiency

- Different types of Vitamin B3

- Health Benefits

- Health Claims

- Best sources of Vitamin B3

- Daily requirements and intake

- How to take Vitamin B3

- Signs and symptoms of deficiency

- Risks and side effects

- Interactions - herbs and supplements

- Interactions - medication

- Summary

- Related Questions

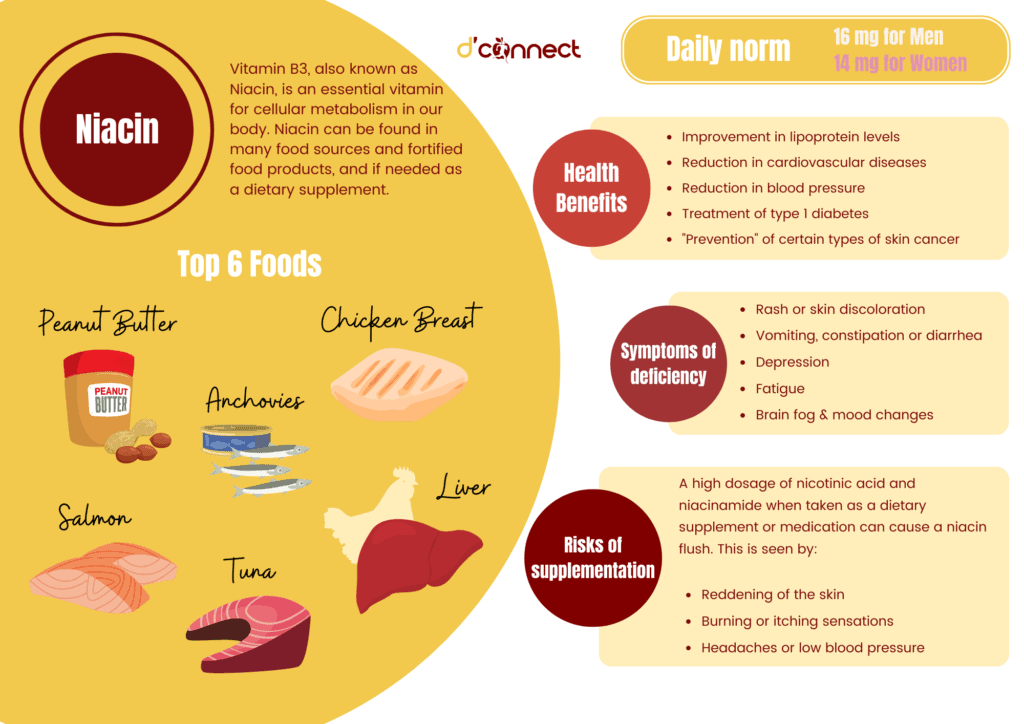

Niacin is an essential vitamin for many cellular functions in the body. It’s found in many food sources and fortified food products, and, if needed, as a dietary supplement.

Several conditions can cause vitamin B3 deficiency, such as

- Anorexia

- Alcohol consumption

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBS)

- Liver cirrhosis

which is why it’s important to eat a diet rich in fresh, whole foods and avoid processed meals.

Niacin deficiency can lead to dermatitis, diarrhea and dementia and if left untreated, to death, as often happened until scientists discovered niacin as being one of the key vitamins for our health.

In the following section, you can read more about the discovery of niacin and its importance and health benefits, as well as potential risks if taken in larger doses.

What is Vitamin B3?

Vitamin B3, also known as niacin, is one of the water-soluble vitamins belonging to the vitamin B (group) complex.

Niacin can be found in many food sources and fortified food products and is available as a dietary supplement.[1]

Source: Alleksana @ Pexels

The discovery of niacin

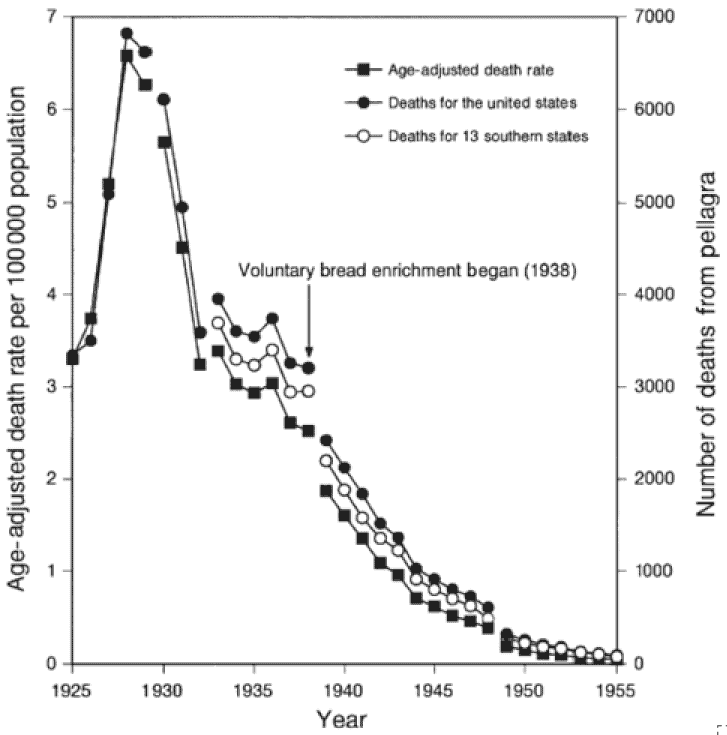

Niacin was recognised as a vitamin in the early 20th century as a result of efforts to understand and treat a widespread human disease called pellagra.[2]

Pellagra is marked by:

- Dermatitis

- Diarrhea

- Dementia

If left untreated, pellagra can lead to death.

In the 1920s, Joseph Goldberger and his fellow researchers concluded that pellagra is a dietary deficiency disease that could be cured by a pellagra-preventive factor or P-P factor that was lacking in corn, but that could be found in meat and milk.

In 1937, agricultural biochemist Conrad Arnold Elvehjem isolated the P-P factor from active liver extracts, showing that the P-P factor is nicotinic acid, which was subsequently named niacin.

Source: Anstey, A. Pellagra: a review with emphasis on photosensitivity. British Journal of Dermatology (2010).

Further animal trials were conducted in pigs, monkeys and humans, and confirmed that niacin is beneficial to curing pellagra in people. Pellagra disappeared after maize meal fortified with niacin became mandatory in 1941.[3]

Vitamin B3 deficiency

In most developed countries, niacin deficiency is very rare. Severe niacin deficiency, or pellagra, mostly occurs in developing countries where diets are not as varied.

Niacin deficiency mostly occurs in developing countries.

Who is most at risk of Vitamin B3 deficiency?

Low niacin in undernourished individuals

People who are undernourished or have

- Anorexia

- AIDS

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Liver cirrhosis

often have inadequate intakes of niacin and other nutrients.

Inadequate intake of niacin is most likely caused by the loss of appetite and impaired absorption of niacin in the body.[1]

Alcohol consumption and niacin absorption

Alcohol can induce niacin deficiency by decreasing availability and/or impairing absorption of niacin, its precursors and other vitamins and nutrients.[4]

Inadequate riboflavin, pyridoxine and iron intake

People who do not consume enough riboflavin (vitamin B2), pyridoxine (vitamin B6) or iron convert less tryptophan to niacin because enzymes in the metabolic pathway for this conversion depend on these nutrients to function.[1]

RELATED — Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin)

Niacin levels and Hartnup disease

Hartnup disease is a rare genetic disorder involving the renal, intestinal and cellular transport processes for several amino acids, including tryptophan.

The disease interferes with the absorption of tryptophan in the small intestine and increases its loss in the urine. As a result, the body has less available tryptophan to convert to niacin.[1]

Niacin intake and Carcinoid syndrome

Carcinoid syndrome is caused by slow-growing tumors in the gastrointestinal tract that release serotonin and other substances.

It is characterized by facial flushing, diarrhea, anorexia and other symptoms.

In those with carcinoid syndrome, tryptophan is oxidised to serotonin and not metabolized to niacin. This results in less available tryptophan to be converted to niacin.[1]

Different types of Vitamin B3

There are two main forms of niacin

- Nicotinic acid

- Niacinamide

Nicotinic acid and niacinamide are similarly effective as a vitamin because the body has the ability to convert them to each other.[5]

Nicotinic acid

Nicotinic acid is also known as niacin and is essential to energy metabolism. It helps the digestive system, skin and nervous systems to function properly.

Niacin is also used as a prescription medication to treat cholesterol problems because of its ability to increase “good” cholesterol (HDL) and decrease “bad” cholesterol (LDL).[6]

Niacinamide

The human body has the ability to convert niacin to niacinamide, and also convert an amino acid called tryptophan to make niacinamide.

Niacinamide is derived from niacin.

Niacinamide is a precursor to two very important biochemical cofactors:

- Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)

- Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP)

All tissue in the body converts absorbed niacin into its main metabolically active form, the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD).

NAD is required by more than 400 enzymes to catalyze reactions in the body, which is more than any other vitamin-derived coenzyme. These catabolic reactions transfer potential energy in carbohydrates, fats and proteins to adenosine triphosphate (ATP).[6]

The body also can convert an amino acid called tryptophan to NAD, so it is also one of the sources of niacin.[6]

Inositol hexanicotinate

We thought that it’s important to mention inositol hexanicotinate.

Since a high dose of niacin is known to lead to flushing, a condition that causes the skin to become red and itchy, inositol hexanicotinate is known as a “no-flush niacin” because it doesn’t contain nicotinic acid.

Health benefits of Vitamin B3

Niacin is known to help treat many conditions, and it may help reduce cardiovascular disease risks and type 1 diabetes, and might have a role in skin cancer prevention.

RELATED — Type 1 Diabetes: Autoimmune disease that is on the rise

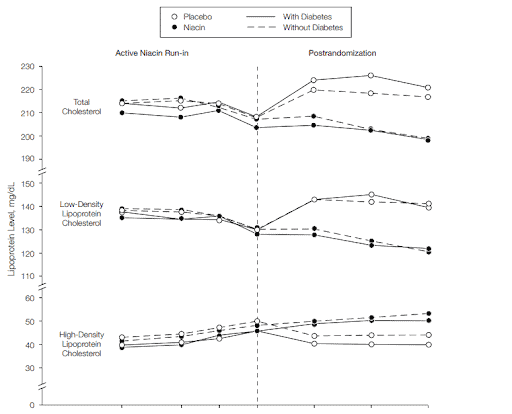

Niacin and improvement in lipoprotein levels

Niacin may help to improve our blood fat levels by

- Increasing high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

- Reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol

- Reducing triglyceride levels

A study by Elam et al. reported that participants who were administered with 3000 mg or maximum-tolerated dosage of niacin per day showed a significant increase in HDL-c by 29% and decreased in triglycerides by 23%-28% and LDL-c by 8%-9% in participants with or without diabetes.[7]

Source: E A Brinton. Effect of niacin on lipid and lipoprotein levels and glycemic control in patients with diabetes and peripheral arterial disease: the ADMIT study: A randomized trial. Arterial Disease Multiple Intervention Trial. (2000)

However, several studies have found no link between niacin supplementation and a decrease in heart disease risk or death. Further studies might be needed to see the effect of niacin supplementation on heart disease risk.

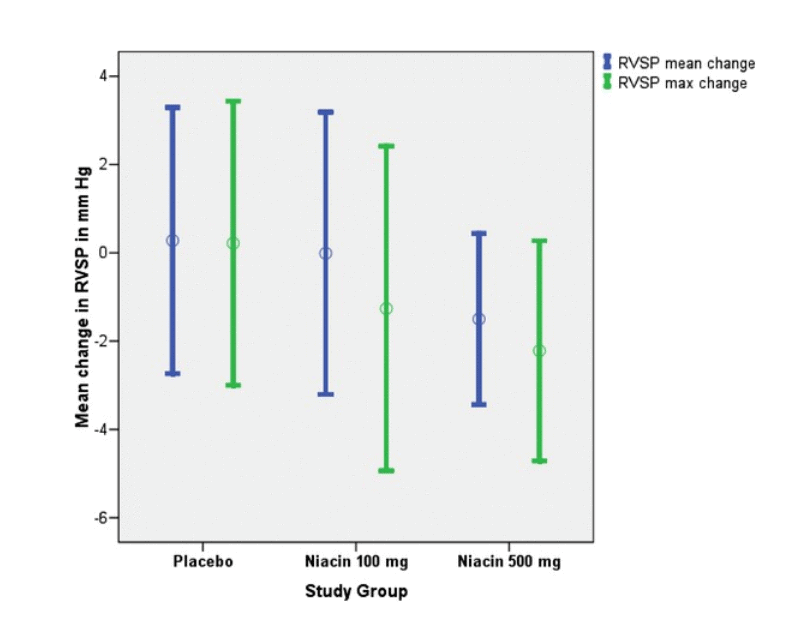

Niacin and reduction in blood pressure

One role of niacin is to release prostaglandins or chemicals that help our blood vessels widen, which improves blood flow and reduces blood pressure.

Niacin may help with high blood pressure.

Research showed that each 1 mg increase in daily niacin intake was associated with a 2% decrease in high blood pressure risk.[8]

A high-quality study by Martin J. McNamara et al. also reported that single doses of 100 mg and 500 mg of niacin slightly reduced right ventricular systolic pressure (RSVP).[9]

Author: Martin J. McNamara, A randomized pilot study on the effect of niacin on pulmonary arterial pressure. (2015)

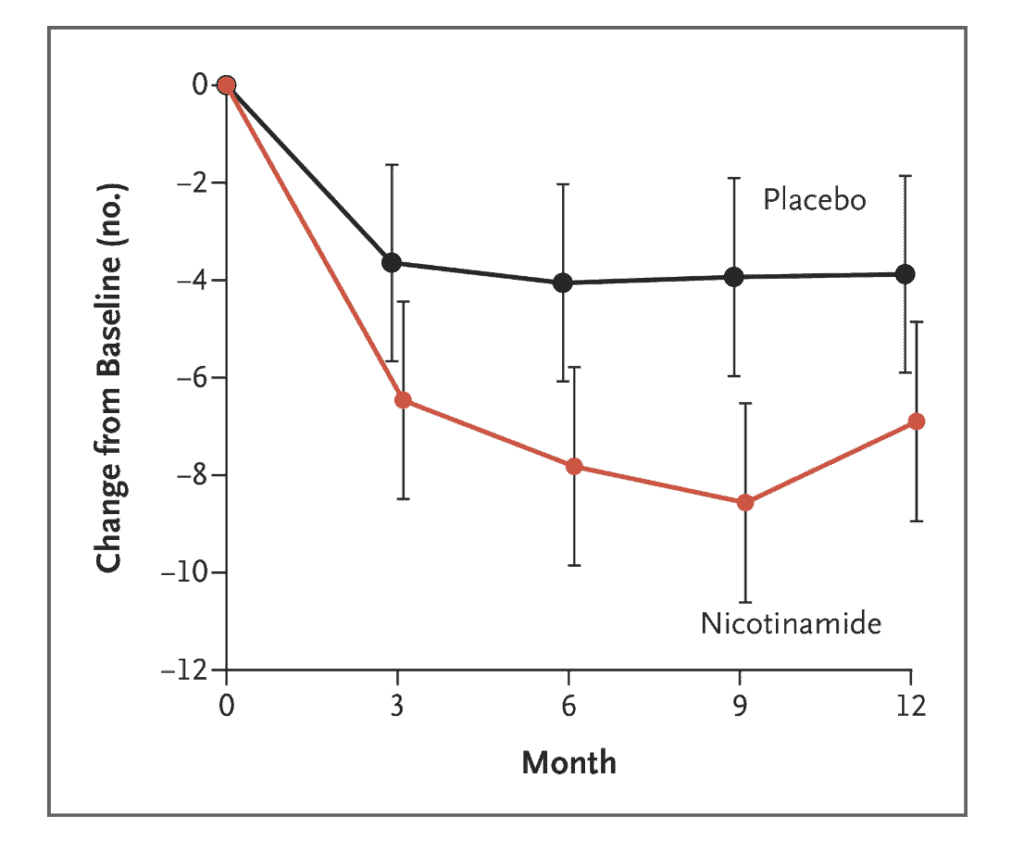

Niacin and skin health

Niacin helps protect skin cells from sun damage, whether used orally or applied as a lotion. Also, it may help prevent certain types of skin cancer.

A study by Andrew C Chen et al. that involved over 300 people who were at high risk of skin cancer found that taking 500 mg nicotinamide twice daily reduced rates of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

This study also found that nicotinamide also reduced the number of actinic keratoses by

- 11% after 3 months

- 14% after 6 months

- 20% after 9 months

- 13% after 12 months

when compared to the placebo group.

Actinic keratoses are patches on the top layer of skin that develop from years of sun exposure.

Source: Diona L Damian,. A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention. (2015)

Health claims that still need more evidence and research

Niacin and treatment of type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease where our body attacks and destroys insulin-creating cells.

Research suggests that niacin could help protect those cells and possibly even lower the risk of type 1 diabetes in children with a higher chance of developing this condition.[10]

However, there are still limited studies on niacin supplementation and its protective effects on type 1 diabetes.

Niacin and brain function

Our brain needs niacin to receive energy and function properly.

Brain fog and psychological symptoms such as extreme mood changes and reduced ability to concentrate are associated with niacin deficiency.[11]

Some types of schizophrenia can be treated with niacin, as it helps undo damage to brain cells caused by niacin deficiency.[12] However, further research is needed because the results are still mixed.

Best sources of Vitamin B3

Niacin is present in a wide variety of foods. Many animal-based foods provide about 5-10 mg of niacin per serving, primarily in the highly bioavailable forms of NAD and NADP.

Plant-based foods provide about 2-5 mg of niacin per serving, mainly as nicotinic acid. In some grain products, however, naturally present niacin is largely bound to polysaccharides and glycopeptides. This makes it only about 30% bioavailable.

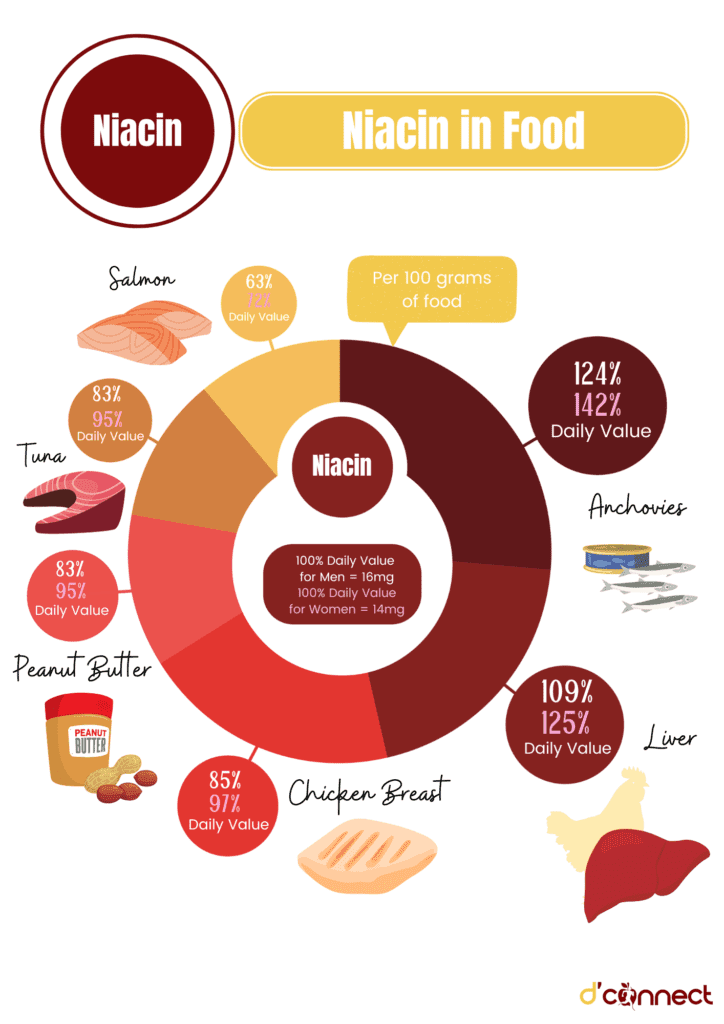

Food Sources | Concentration (mg/100g) | Daily Value (DV) Men/Women |

Anchovies | 19.9mg | 124% / 142% |

Liver | 17.5mg | 109% / 125% |

Skinless chicken breast | 13.7mg | 85% / 97% |

Peanut butter | 13.4mg | 83% / 95% |

Tuna | 13.3mg | 83% / 95% |

Salmon | 10.1mg | 63% / 72% |

Turkey | 7.5mg | 46% / 53% |

Pork (lean) | 7.4mg | 46% / 52% |

Ground beef (lean) | 7.3mg | 45% / 52% |

Mushrooms (white, raw) | 3.6mg | 22% / 25% |

Whole-wheat | 2.3mg | 14% / 16% |

Green peas | 2.1mg | 13% / 15% |

Avocado | 1.7mg | 10% / 12% |

Brown rice | 1.5mg | 9% / 10% |

Potatoes | 1.4mg | 8% / 10% |

Only 30% of niacin is absorbed by our body.

Niacin is added to many breads, cereals and infant formulas to enrich and fortify foods, making it highly bioavailable.

Daily requirements and recommended intake

The recommended daily allowance (RDA) for niacin depends on age and gender, as we shared below.

Important note: 1 NE equals 1 mg niacin or 60 mg of the amino acid tryptophan, which the body can convert to niacin.

Age | Male | Female |

Birth to 6 months | 2mg | 2mg |

7-12 months | 4mg NE | 4mg NE |

1-3 years | 6mg NE | 6mg NE |

4-8 years | 8mg NE | 8mg NE |

9-13 years | 12mg NE | 12mg NE |

14-18 years | 16mg NE | 14mg NE |

19+ years | 16mg NE | 14mg NE |

Pregnant and lactating women should add an additional 3mg – 4mg of niacin to their diet or supplementation.

How to take Vitamin B3 as a supplement

Nicotinic acid and nicotinamide are the two most common forms of niacin supplements.

Vitamin B3, in the form of nicotinic acid or niacinamide, is available as a supplement either by itself or alongside other vitamins and minerals in doses ranging from 14 to 1,000 mg per serving.

Niacin is available in

- Multivitamin-mineral products

- Supplements containing other B-complex vitamins

- Supplements containing niacin only

Some niacin-only supplements contain 500 mg or more per serving, which is much higher than the recommended intake.

Nicotinic acid in supplemental amounts beyond nutritional needs can cause skin flushing. On the other hand, niacinamide does not produce skin flushing because it has a slightly different chemical structure.

For dietary supplements, at first, 500 mg per day is taken at bedtime. However, it is best to talk with a healthcare provider about the right dosage for you.

Common signs and symptoms of Vitamin B3 deficiency

Severe niacin deficiency is known as pellagra and can cause symptoms such as

- Pigmented rash or brown discolouration on skin

- Rough or sunburned-like appearance of the skin

Pellagra also can cause a bright red tongue and changes in the digestive system that lead to

- Vomiting

- Constipation or diarrhea

Furthermore, pellagra also could affect the neurological symptoms which include:

- Depression

- Apathy

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Memory loss (that can progress to aggressive, paranoid and suicidal behaviours and auditory and visual hallucinations).

If pellagra progresses and is untreated, anorexia can develop and the affected individual can eventually die.[1]

Vitamin B3 risks and side effects

No adverse effects have been found from the consumption of naturally occurring niacin in foods.

However, a high dosage of nicotinic acid and niacinamide when taken as a dietary supplement or medication can cause an adverse effect called niacin flush.[13]

This causes a reddening of the skin along with burning or itching sensations and may be accompanied by headaches or low blood pressure.[1]

The side effects are typically transient and can occur within 30 minutes of intake or over days or weeks with repeated dosing.

Possible interactions with herbs and supplements

Possible interactions might happen between niacin and zinc. Taking zinc with niacin might worsen niacin side effects such as flushing and itching.

Possible interactions with medications

Antibiotics

Niacin should not be taken at the same time as tetracycline because it interferes with the absorption and effectiveness of this medication.

Anticoagulants (blood thinners)

When combined with blood thinners, niacin may increase the risk of bleeding.

Blood pressure medications

Niacin can enhance the effects of medications such as alpha blockers, which may lead to the risk of low blood pressure.

Isoniazid and pyrazinamide

Isoniazid and pyrazinamide are used to treat tuberculosis. They can interrupt the production of niacin from tryptophan by competing with a vitamin B6-dependent enzyme required for this process. Furthermore, isoniazid can interfere with niacin’s conversion to NAD.

Anti-diabetic medications

Large doses of nicotinic acid can raise blood glucose levels.

Some studies have found that nicotinic acid doses of 1.5 g/day or more are most likely to increase blood glucose levels in individuals with or without diabetes.

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

Regarding this condition, people who take anti-diabetic medications should be monitored more frequently because they might need dose adjustments.

Summary

Key Takeaway – In this summary illustration we have outlined the most important information that you should know about Niacin (vitamin B3).

Related Questions

1. Does vitamin B3 help with cholesterol?

Studies conducted since the 1950s show that niacin (vitamin B3) increases HDL (good) cholesterol levels by 10-30% and reduces LDL (bad) cholesterol levels by 10-25%.

These positive changes might reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases.[14]

2. How do you stop a niacin flush?

To reduce niacin flushing effects, take smaller amounts of nicotinic acid supplement with food. Over time, slowly increase the dose, and the body should develop a natural tolerance.

3. Why is niacin added to energy drinks?

Niacin helps convert food into energy which is why it’s used in beverages.

Niacin’s active form, NAD, is involved in the catabolic reaction, which transfers carbohydrates, proteins and fats to adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

You may want to read our first article on vitamin B complex: Vitamin B1 (Thiamine).

Bernadeth’s passion in cooking, food and health led her to learn more about nutrition and the importance of functional foods. Throughout the years, she gained special interest in sports and performance nutrition, and the varieties of diets around the world. As a nutritionist, Bernadeth’s goal is to encourage a healthy-balanced diet and share the evidence-based nutrition knowledge in order for people to live healthier and longer lives.

Bernadeth is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect.

References

(1) National Institute of Health. (2021). Niacin – Health Professional Factsheet [Internet]. Retrieved 18th of July 2022 from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Niacin-HealthProfessional/

(2) Lanska D, J. (2012). The Discovery of Niacin, Biotin, and Pantothenic Acid. Ann Nutr Metab. 61:246-253. Retrieved from https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/343115

(3) Commonwealth of Australia. (2006). Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Retrieved 20th of July 2022 from https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients/niacin

(4) Badawy A. A. (2014). Pellagra and alcoholism: a biochemical perspective. Alcohol and alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), 49(3), 238–250. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu010

(5) National Institute of Health. (2021). Niacin – Fact Sheet for Consumers. Retrieved 19th of July 2022 from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Niacin-Consumer/

(6) Gehring W. (2004). Nicotinic acid/niacinamide and the skin. Journal of cosmetic dermatology, 3(2), 88–93. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6650737_Nicotinic_acidniacinamide_and_the_skin

(7) Elam, M. B., Hunninghake, D. B., Davis, K. B., Garg, R., Johnson, C., Egan, D., Kostis, J. B., Sheps, D. S., & Brinton, E. A. (2000). Effect of niacin on lipid and lipoprotein levels and glycemic control in patients with diabetes and peripheral arterial disease: the ADMIT study: A randomized trial. Arterial Disease Multiple Intervention Trial. JAMA, 284(10), 1263–1270. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.10.1263

(8) Zhang, Z., Liu, M., Zhou, C., He, P., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Li, Q., Liu, C., & Qin, X. (2021). Evaluation of Dietary Niacin and New-Onset Hypertension Among Chinese Adults. JAMA network open, 4(1), e2031669. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31669

(9) McNamara MJ, Sayanlar JJ, Dooley DJ, Srichai MB, Taylor AJ. (2015). A randomized pilot study on the effect of niacin on pulmonary arterial pressure. Trials. 2015 Nov 21;16:530. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4654874/

(10) Skyler J. S. (2013). Primary and secondary prevention of Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association, 30(2), 161–169. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12100

(11) Wang, W., & Liang, B. (2012). Case report of mental disorder induced by niacin deficiency. Shanghai archives of psychiatry, 24(6), 352–354. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267046110_Case_report_of_mental_disorder_induced_by_niacin_deficiency

(12) Xu, X. J., & Jiang, G. S. (2015). Niacin-respondent subset of schizophrenia – a therapeutic review. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences, 19(6), 988–997. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25855923/

(13) Meyer-Ficca, M., & Kirkland, J. B. (2016). Niacin. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 7(3), 556–558. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3945/an.115.011239

(14) MacKay, D., Hathcock, J., & Guarneri, E. (2012). Niacin: chemical forms, bioavailability, and health effects. Nutrition reviews, 70(6), 357–366. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22646128/