Emily Brown

BSc (Human Nutrition)

Note — The article was checked and updated July 2023.

Jump to:

- What is Vitamin D?

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Different types of Vitamin D

- Health Benefits

- Health Claims

- Best sources of Vitamin D

- Daily requirements and intake

- How to take Vitamin D

- Signs and symptoms of deficiency

- Risks and side effects

- Interactions - herbs and supplements

- Interactions - medication

- Summary

- Related Questions

Vitamin D levels were commonly tested for up to a few years ago. Then, it suddenly stopped, and today several sources report that doctors can recommend supplementation without the need for serum testing.

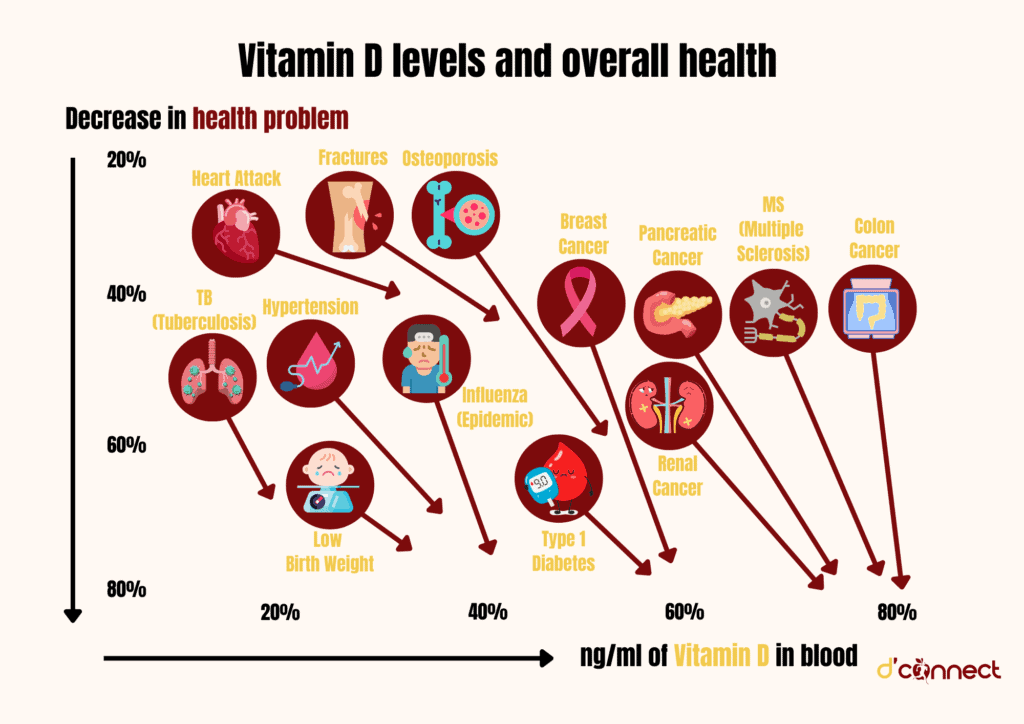

For our body to absorb calcium and maintain healthy bone structure and density, it needs vitamin D. This is important for children, and also for adults, because as we get older we can suffer from osteoporosis.

Vitamin D reduces inflammation in the body, assists our immune system to stay in check, and even reduces cancer cell growth.

But before we go into details such as health benefits, let us first start with history and see how vitamin D was discovered.

What is Vitamin D?

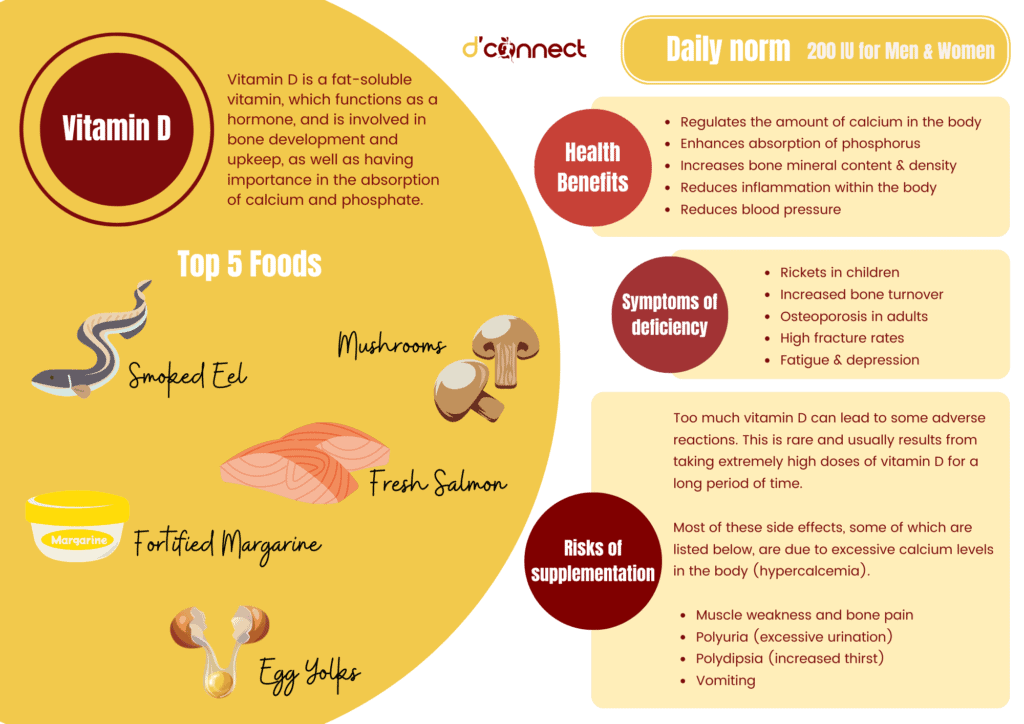

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin, which functions as a hormone, and is involved in bone development and upkeep, as well as having importance in the absorption of calcium and phosphate.[1,2]

The main source of vitamin D is ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from the sun.

We can also get vitamin D in small quantities (measured in micrograms, µg, or international units, IU) from our diet and supplements.[3]

Deficiency in vitamin D causes rickets, a bone softening condition first described in the late 17th century. During this industrial era, the heavily polluted skies of the United Kingdom significantly impacted the amount of UV radiation that could get through, and the prevalence of rickets sored.[4]

Rickets was referred to as the “English Disease”

To understand the disease better, in 1919, biochemist Sir Edward Mellanby fed his dogs a typical UK diet of grains to see if it was the English diet that was the cause of rickets.

He unintentionally also kept the dogs away from sunlight, which resulted in the development of rickets. Mellanby then cured the dogs by adding cod liver oil to their diet.

This led to the assumption that the recent discovery of vitamin A, in cod liver oil, prevented rickets.

However, in 1922, biochemist Elmer V. McCollum discovered that a modified version of cod liver oil, which had been heated and oxidised, destroying the vitamin A, still helped to cure the disease.

This meant that there must have been another vitamin in the oil responsible for curing the English Disease. This new vitamin was named “vitamin D,” as it was the fourth discovered vitamin following vitamins A, B and C.[4]

RELATED — Vitamin C: Immunity and Collagen Booster

In 1925, Alfred F Hess and his team discovered that humans themselves could produce vitamin D when their skin was exposed to sunlight.

The structure of vitamin D was discovered in 1932, and a pre-form of vitamin D was first synthesised in 1935. The US began to fortify their milk with vitamin D to combat rickets in the late 1930s, which was done with great success.[4]

Vitamin D deficiency

Low vitamin D levels are not uncommon, as there are only a few foods that provide an adequate amount in our diet.

Therefore, it is necessary to receive vitamin D from the diet and the sun to avoid deficiency.[5]

In 2008 / 2009, when the last national nutrition survey in New Zealand was conducted, more than a quarter of adults were below recommended vitamin D levels, with nearly 5% being deficient.[6]

There are no worldwide statistics on vitamin D deficiency, as there is no universal recommended serum vitamin D levels. However, it seems that vitamin D deficiency is prevalent worldwide.[2]

The Ministry of Health recommendations for vitamin D (25(OH)D) levels are outlined below:[6]

Annual Mean Vitamin D (serum 25(OH)D) levels | |

Excessive/ unsafe levels | More than 160 nmol/L (60 ng/mL) |

Recommended level | 50 nmol/L or greater (20 ng/mL) |

Insufficient level | Less than 50 nmol/L |

Mild to moderate deficiency | Less than 25 nmol/L (10 ng/mL) |

Severe deficiency | Less than 12.5 nmol/L (5 ng/mL) |

Vitamin D – Status indicators used in New Zealand Adult Nutrition Survey 2008/09

Note — The guidelines for vitamin D levels will change slightly depending on where you get your blood tested.

Who is most at risk of Vitamin D deficiency?

Insufficient sun exposure

Sun exposure provides the majority of our vitamin D. People who are not sufficiently exposed to sunlight, such as those who are

- confined indoors

- hospitalised (in the long term)

- cover their skin for cultural reasons

are at risk of vitamin D deficiency.[1]

Older adults and vitamin D synthesis

Due to aging, the skin of older adults cannot synthesise vitamin D as efficiently. They are also more likely to spend more time indoors.[1]

Darker skin and vitamin D absorption

Pregnant, breastfeeding women, breastfed infants, and vitamin D

Both pregnant and breastfeeding women are at risk of deficiency.

Breast milk is not a good source of vitamin D

This means that breastfed babies are also at risk of vitamin D deficiency. If your doctor thinks your baby is at risk, they will prescribe supplements in the form of drops.[3,6]

Liver and kidney disease, and vitamin D conversion

People with impaired function of their liver or kidneys are less able to convert vitamin D into its active form, calcitriol, which is involved in all the functions of vitamin D.[2]

Gastrointestinal issues and malabsorption of vitamin D

People who cannot absorb fat will have more difficulty absorbing enough vitamin D from food and may benefit from supplements. Examples of malabsorption syndromes are

- Coeliac disease

- Cystic fibrosis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Gastric bypass.[2]

Obesity and vitamin D fat storage

People with obesity are more likely to suffer from vitamin D deficiency due to the reduced bioavailability of vitamin D, as it is stored in body fat.[1]

Different types of Vitamin D

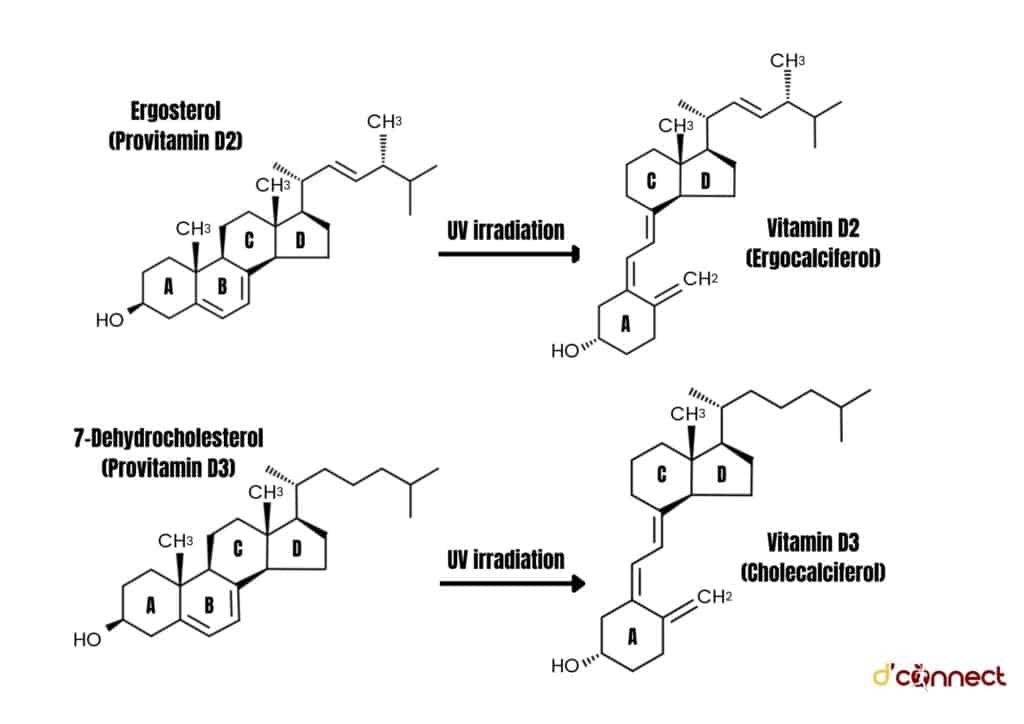

There are two types of vitamin D, these are

- vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol)

- vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol)

Both of these vitamin forms are processed in the small intestine to form calcidiol (25(OH)D) in the liver, and then calcitriol (1,25(OH)2D) in the kidneys.[8]

Vitamin D2

Vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) is produced by UV irradiation of ergosterol (a plant steroid), and can be consumed via plant-foods and fungi.

RELATED — The health benefits of mushrooms and fungi

Due to the chemical structure, vitamin D2 has a lower affinity for the receptor, and is therefore cleared faster from the body, while also being less bioavailable.[9,10]

Vitamin D3

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is mostly sourced from

- natural production in our skin (UVB radiation from the sun)

- converting pre-vitamin 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) to vitamin D3

Vitamin D3 can also be consumed from animal foods, such as fish, fish oils, and shellfish.

This form binds better with its receptor, and is therefore more bioavailable and helps maintain vitamin D levels longer.[9,10]

Calcidiol or 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) is the main circulating form of vitamin D, and is the main measure of a person’s vitamin D levels.[9]

Calcitriol or 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) is the metabolized form of vitamin D most involved in metabolic processes.[9]

Health benefits of vitamin D

Many tissues throughout the body contain vitamin D receptors, including our

- skeleton

- intestines

- bone marrow

- brain

- colon

- breast and immune cells

This suggests vitamin D has different functions throughout the body, some of which are outlined below.[11]

Vitamin D regulates the amount of calcium in the body

When calcium levels in the blood decrease, calcitriol promotes calcium reabsorption in the kidneys and small intestines, and also increases bone demineralisation, which releases calcium back into the bloodstream.[8]

Vitamin D enhances absorption of phosphorus

Vitamin D increases bone mineral content and bone mineral density

Levels of 25(OH)D in the blood are directly related to bone mineral density in adults. Lower levels of vitamin D can lead to low calcium levels.

This is when the body will “break down” bones to increase our blood calcium, but this process weakens the strength of our bones.[2]

Vitamin D and the immune system

Vitamin D acts on immune cells throughout the body, reducing inflammation, which may in turn benefit people suffering with autoimmune diseases, such as Type 1 Diabetes and Multiple Sclerosis.

RELATED — Type 1 Diabetes: Autoimmune disease that is on the rise

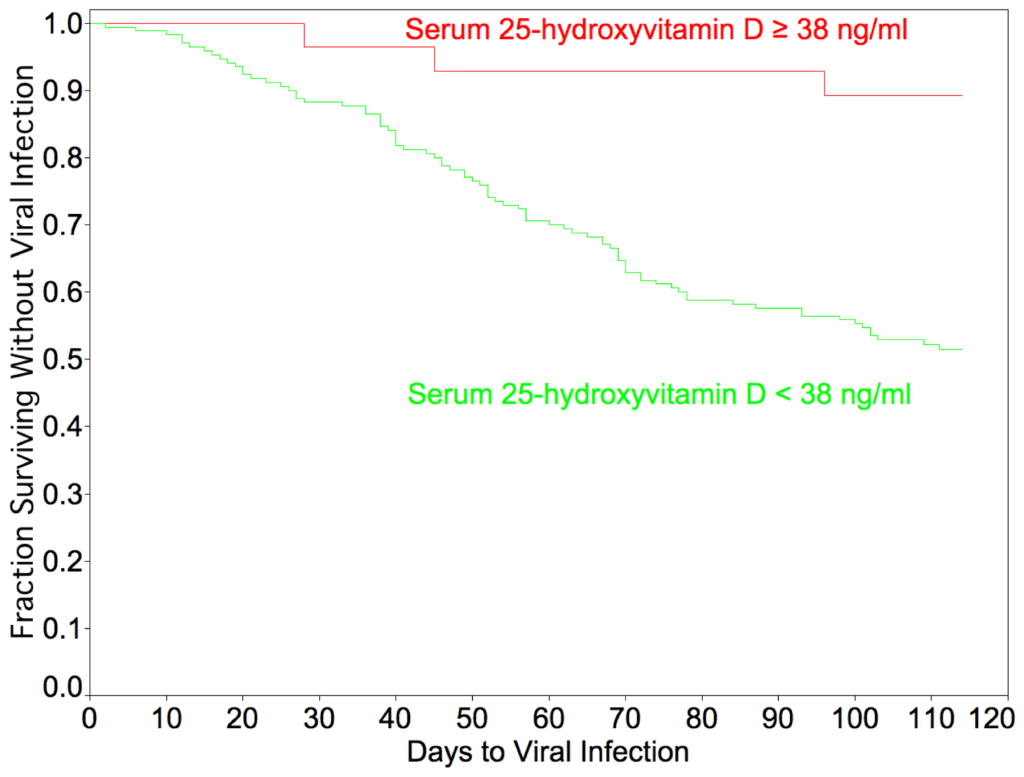

A higher vitamin D concentration has also shown to decrease our risk of the common cold by 2.7 times, and reduce the number of days being ill by 4.9 times.[11,13]

Source: Sabetta, J.R., et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and the incidence of acute viral respiratory tract infections in healthy adults. (PloS one, 2010).

Vitamin D and healthy skin

Some studies have found a link between low vitamin D levels and psoriasis, but this relationship is not well understood.

It is hypothesised that this is due to the anti-inflammatory properties of vitamin D. Calcitriol or 1,25(OH)2D has also shown to inhibit the growth of bacteria responsible for acne.[14]

Vitamin D and muscle strength

Vitamin D supplementation has been shown to be beneficial on muscle strength, balance, and ease of walking, especially in the elderly population.[15]

Vitamin D prevents hypocalcemic tetany

A healthy vitamin D level will help prevent hypocalcemic tetany, which is involuntary muscle contractions, resulting in cramps and muscle spasms.

This painful symptom is normally due to low calcium levels, which can occur with low vitamin D levels.[16]

Vitamin D reduces blood pressure

Higher levels of 25(OH)D in the blood may reduce the risk of high blood pressure, but more evidence is needed.[17]

Vitamin D lowers chances of heart attacks

By reducing blood pressure, higher levels of 25(OH)D in the blood can reduce the risk of heart attacks.

In one study, individuals with vitamin D concentrations below 15ng/mL have a 60% increased risk of heart disease compared to those with higher concentrations.[18]

Vitamin D and rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Increased vitamin D intake has been linked to a lower risk of RA and effective treatment of RA.

It has been shown that 25(OH)D plasma levels reduce the annual cycle of RA and prevent the disease from worsening in the winter months.[19]

Vitamin D and cancer cell growth inhibition

Individuals with higher vitamin D blood levels have a decreased risk of cancer mortality compared to individuals with lower levels, but it does not decrease the risk of developing cancer.

Vitamin D interferes with cancerous growth factors, preventing tumour cells from multiplying and spreading.[20,21]

Vitamin D and skincare

Vitamin D has also become an increasingly popular ingredient in our skincare products and can help improve our serum 25(OH)D levels when applied topically.

The anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties of vitamin D are also believed to reduce inflammation and protect against environmental pollution, but there is limited research to support this claim.[22]

Health claims that still need more evidence and research

Vitamin D supplementation can help protect us from COVID-19.

Research has found that patients suffering from COVID-19 have lower levels of serum vitamin D, as well as zinc and calcium.

Best sources of Vitamin D

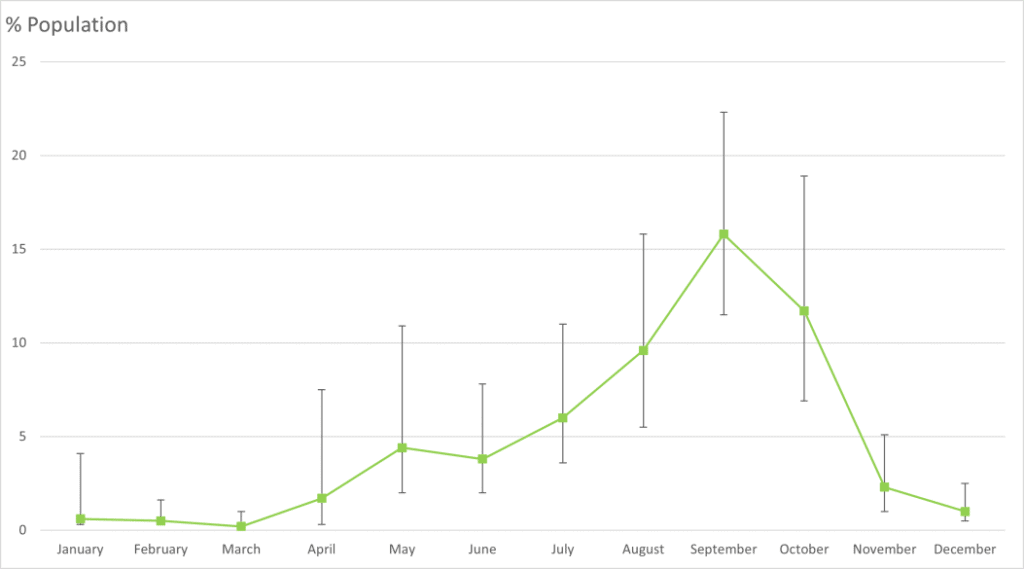

The main source of vitamin D is from exposure to the sun and will account for about 80% of our vitamin D supply.

In fact, 10 to 15 minutes of entire body exposure in the midday summer sun is the same as taking a 375 µg supplement.

In summer, 10 minutes in the sun (3 times a week) is sufficient for healthy levels of vitamin D

Source: Environmental Health Intelligence New Zealand. Vitamin D deficiency.

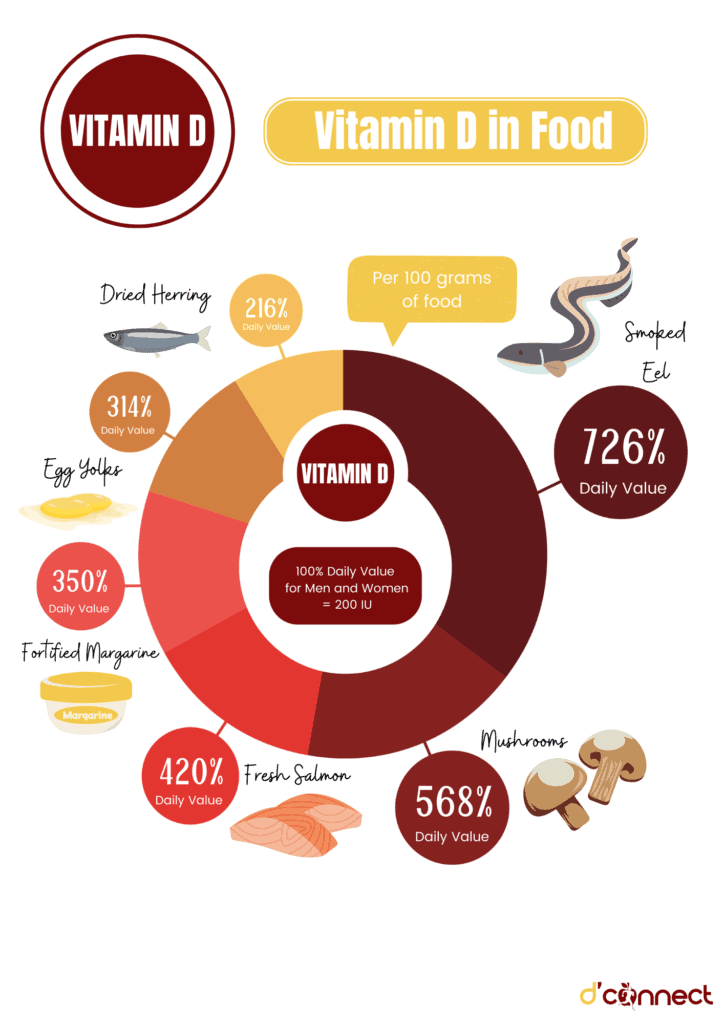

The table below lists the food sources highest in vitamin D.[26]

The concentration is calculated by the amount of vitamin D per 100g, which differs from serving size.

Food Sources | Concentration (µg/100g) | Daily Value (DV) Men / Women |

Eel, smoked | 36.3 (1 ⅓ serving) | 726% |

Mushrooms | 28.4 (1 serving) | 568% |

Salmon, fresh | 21 (1 ⅓ serving) | 420% |

Margarine, fortified | 17.5 (7 tablespoons) | 350% |

Egg yolks | 15.7 (6 eggs) | 314% |

Herring, dried | 13 (2.5 fillets) | 260% |

Tuna, canned | 11.3 (1 small can) | 226% |

Salmon, canned | 11.3 (1 small can) | 226% |

Sardines, canned | 10.8 (1 small can) | 216% |

Cereal, rice flakes | 7.6 (7 ½ servings) | 152% |

Cheese | 7.5 (10 servings) | 150% |

Mackerel, canned | 6.3 (1 small can) | 126% |

Beef liver | 1.2 (1 slice) | 24% |

Milk and juices, fortified | 1.1 (½ serving) | 22% |

*Cod Liver Oil | 250 (22 teaspoons) | 5000% |

Note — Usually, the dosage for cod liver oil is 2-3 teaspoons, which provides around 500% of daily value. However, in our nutrient tables we use “vitamin concentration” per 100 grams of food.

Daily requirements and recommended intake

Currently, for vitamin D the research only recommends the value for adequate intake.

Adequate Intake (AI) is a type of daily value (DV) recommendation determined by the nutritional intakes of healthy people.

The AI is only used when there is not enough research on the micronutrient to form a more evidence-based recommendation.[27]

The AI for vitamin D is listed in the table below, in both micrograms, µg and IU (international units).[28]

Adequate intake (AI) | ||||

Age | Male | Female | ||

0 – 12 months | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day |

1 – 18 years | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day |

19 – 30 years | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day |

31 – 50 years | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day |

51 – 70 years | 10.0 µg/day | 400 IU/day | 10.0 µg/day | 400 IU/day |

>70 years | 15.0 µg/day | 600 IU/day | 15.0 µg/day | 600 IU/day |

Pregnancy | – | – | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day |

Breastfeeding | – | – | 5.0 µg/day | 200 IU/day |

Note — During pregnancy and lactation, the Ministry of Health suggests no additional increase in vitamin D intake.

However, for women with little access to sunlight they recommend a daily supplement of 10 µg to avoid deficiency.[28]

How to take Vitamin D

Taking vitamin D supplements with the largest meal of the day can improve absorption of vitamin D by 50%.

There is limited evidence on the best time of the day to take Vitamin D.

Common signs and symptoms of Vitamin D deficiency

Vitamin D deficiency can be quite common. However, being deficient in vitamin D does not always result in having symptoms.

Majority of people with vitamin D deficiency are asymptomatic

Some side-effects that can be observed from vitamin D deficiency are described below.[2]

Vitamin D and rickets in young children (bowed legs and knocked knees)

Rickets is caused by impaired bone mineralisation due to low calcium and phosphate levels, caused by vitamin D deficiency.

This leads to abnormalities in the growth plates of children, weakened bones and skeletal deformities.[8]

Low vitamin D and increased bone turnover

The low calcium and phosphorus levels associated with vitamin D deficiency cause the body to release a hormone called parathyroid hormone (PTH).

This increases the activity of osteoclasts, which break down our bones at an accelerated rate in order to release calcium and phosphorus back into the blood.[2]

Osteoporosis in adults

Increased bone turnover reduces our bone mineral density and leads to osteoporosis. This condition, where our bones become weak and brittle, means that bones can fracture even from the slightest bump or fall.[1]

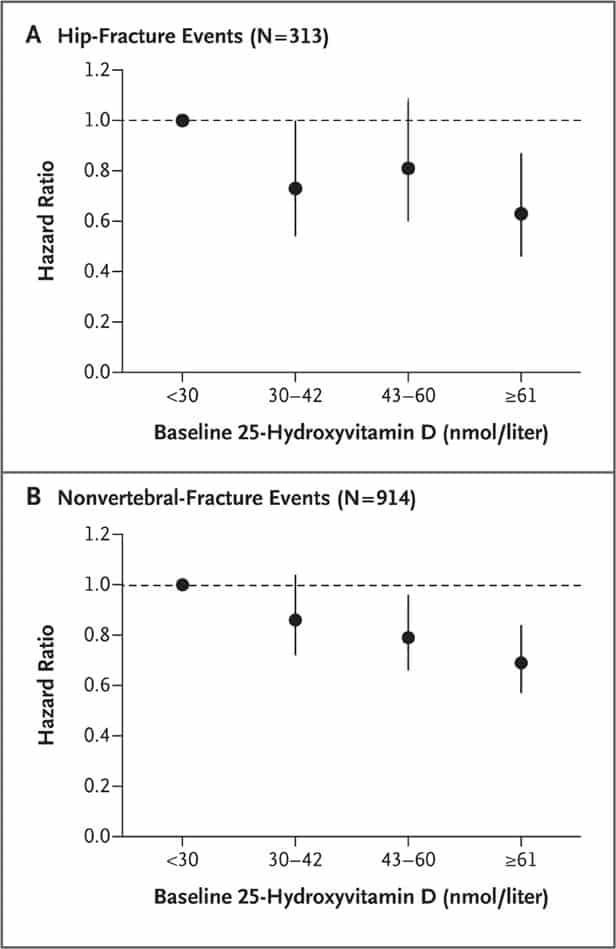

Vitamin D deficiency and fracture rates

Some studies found that supplementing people with 20 µg vitamin D3 every day reduced the risk of hip fractures by 30% and the risk of non-vertebral fractures by 14%.[31]

Source: Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A., et al. A Pooled Analysis of Vitamin D Dose Requirements for Fracture Prevention. (New England Journal of Medicine, 2012).

Low levels of vitamin D and fatigue

A lesser known sign of vitamin D deficiency can be fatigue. Research found that vitamin D supplementation greatly increased both self-rated mental and physical energy levels on a scale from 1 to 5, in people suffering from vitamin D deficiency.[32]

Vitamin D deficiency and bone pain

Osteomalacia (the softening of the bones due to low bone density), is linked to generalised bone pain.

A study has shown that 93% of people aged between 10 and 65 who were admitted to hospital with bone pain were deficient in vitamin D.[12]

Vitamin D levels and our muscles (weakness, aches and cramps)

Mood changes and depression and link to vitamin D

Vitamin D risks and side effects

Too much vitamin D can lead to some adverse reactions. This is rare and usually results from taking extremely high doses of vitamin D for a long period of time.

Most of these side effects are due to excessive calcium levels in the body (hypercalcemia).[8]

Some of the milder symptoms of too much vitamin D include:[2]

- Confusion

- Vomiting

- Polyuria (excessive urination)

- Polydipsia (increased thirst)

- Muscle weakness

- Bone pain

- Constipation

If the levels get too high, or are high for a long period of time, this may result in more severe side effects such as[2]

- Anorexia

- Nephrocalcinosis (calcium deposits in the kidneys)

- Ataxia (a disease of the brain resulting in slurred speech, stumbling, and incoordination).

Possible interactions with herbs and supplements

Currently, there are no known interactions between vitamin D supplementation and other vitamins and supplements.

St. John’s Wort (hyperforin) is a popular botanical herb used for its antidepressant activity, but it can also increase the clearance of vitamin D from the body. Over time this may lead to vitamin D deficiency if it is not monitored.[35]

RELATED — St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Possible interactions with medications

Statin drugs and cholestyramine (cholesterol-lowering drugs) can interfere with vitamin D metabolism, and vitamin D supplementation is not recommended on these drugs.

Antiseizure drugs such as phenobarbital (Dilantin) can also affect vitamin D and calcium absorption.[36]

The common weight loss drug Orlistat, as well as steroid medications (e.g. prednisone) can reduce our absorption of vitamin D.[36]

Some drugs when taken can increase our levels of vitamin D, and with vitamin D supplementation can increase our risk of hypercalcemia. These include

- thiazide diuretics (blood pressure medication)

- calcipotriene (common psoriasis medication)[36]

Lastly, the absorption of aluminium, which is found in most antacids, can be increased by vitamin D, which can damage the kidneys. To avoid this, take vitamin D either two hours before or four hours after antacids.[36]

Summary

Key Takeaway – In this summary illustration we have outlined the most important information that you should know about vitamin D.

Related Questions

1. How much vitamin D should you take for a cold?

Taking vitamin D supplements when we feel sick is much too late and will do nothing to avoid the cold. Our vitamin D levels must be maintained at a healthy level for a while to reap the benefits.

If you are deficient in vitamin D, your doctor may recommend a capsule with 1.25 mg (50 000 IU) of vitamin D3 every month, which will help prevent you from getting sick.[13]

2. What is the best way to absorb vitamin D?

Because vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin, it is best absorbed when taken with fatty foods.

If you are taking a vitamin D supplement, it would be best to take it with meals containing oils, nuts, oily fish, and avocado.[30]

3. Can vitamin D cause constipation?

Taking too much vitamin D can lead to hypercalcemia and cause some stomach discomfort and constipation.

However, if your vitamin D levels are within a healthy range and you are taking vitamin D supplement as directed, you should be fine.[2]

4. Can vitamin D deficiency cause hair loss?

Vitamin D has been shown to be involved in the growth of hair follicles and studies have shown a link between low vitamin D levels and hair loss.

However, it has not been shown whether vitamin D supplements can correct hair loss and further studies are needed.[37]

5. Will vitamin D help you sleep better?

Research has linked low vitamin D levels to an increased risk of sleep disorders, but there is little evidence that supplementation will help to treat them.

It has been shown that people with limited sun exposure may benefit from supplementation to help with sleep duration, but for the general population supplementation has shown no effect on sleep.[38,39,40]

For more similar articles on vitamins and minerals, please see our Nutrients section.

Emily is currently pursuing a Masters degree in Advanced Nutrition Practice. Her focus is on the role nutrition plays in physical activity and sport performance, while also gaining a better understanding of the nutritional treatments for Type 2 Diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, which are major contributors to health complications in New Zealand.

Emily’s interest in nutrition stems from her personal experience in sport at an elite level and the importance of diet regarding our performance and capabilities. Upon completion of her postgraduate studies, she intends to gain qualifications as a Registered Nutritionist and progress towards a career of a Sports Nutritionist.

Emily is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect.

References

(1) Nair, R. and A. Maseeh. (2012). Vitamin D: The “sunshine” vitamin. Journal of pharmacology & pharmacotherapeutics, 3(2), 118-126. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3356951/

(2) Sizar, O., et al. (2021, Jul 21, 2021). Vitamin D Deficiency. StatPearls. Accessed Apr 16, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532266/

(3) Ministry of Health and Cancer Society of New Zealand, Consensus Statement on Vitamin D and Sun Exposure in New Zealand, Ministry of Health, Editor. 2012: Wellington.

(4) Deluca, H.F. (2014). History of the discovery of vitamin D and its active metabolites. BoneKEy reports, 3, 479-479. Accessed Apr 12, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3899558/

(5) Fuller, K.E. and J.M. Casparian. (2001). Vitamin D: balancing cutaneous and systemic considerations. South Med J, 94(1), 58-64. Accessed Apr 13, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.direct-ms.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/FullerVitaminD.pdf

(6) Ministry of Health, Vitamin D Status of New Zealand Adults: Findings from the 2008/09 New Zealand Adult Nutrition Survey, Ministry of Health, Editor. 2012, Ministry of Health: Wellington. Accessed Apr 13, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/vit-d-status-nzadults.pdf

(7) Parva, N.R., et al. (2018). Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency and Associated Risk Factors in the US Population (2011-2012). Cureus, 10(6), e2741-e2741. Accessed Apr 19, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6075634/

(8) Pludowski, P., et al. (2018). Vitamin D supplementation guidelines. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 175, 125-135. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960076017300316

(9) Diamond, T.H., et al. (2005). Vitamin D and adult bone health in Australia and New Zealand: a position statement. Medical Journal of Australia, 182(6), 281-285. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06701.x

(10) Joseph, M. (2020, Dec 29, 2020). Vitamin D2 vs. D3: An Evidence-Based Comparison. Nutrition Advance. Accessed Apr 19, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.nutritionadvance.com/vitamin-d2-vs-d3/

(11) Aranow, C. (2011). Vitamin D and the immune system. Journal of investigative medicine : the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research, 59(6), 881-886. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3166406/

(12) Holick, M.F. (2007). Vitamin D Deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(3), 266-281. Accessed Apr 20, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra070553

(13) Sabetta, J.R., et al. (2010). Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and the incidence of acute viral respiratory tract infections in healthy adults. PloS one, 5(6), e11088. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0011088

(14) Mostafa, W.Z. and R.A. Hegazy. (2015). Vitamin D and the skin: Focus on a complex relationship: A review. Journal of advanced research, 6(6), 793-804. Accessed Apr 20, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4642156/

(15) Halfon, M., O. Phan, and D. Teta. (2015). Vitamin D: a review on its effects on muscle strength, the risk of fall, and frailty. BioMed research international, 2015, 953241-953241. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4427016/#B32

(16) Hernández, A. Tetany. Osmosis from ELSEVIER. Accessed Apr 20, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.osmosis.org/answers/tetany

(17) Vimaleswaran, K.S., et al. (2014). Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: a mendelian randomisation study. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 2(9), 719-729. Accessed Apr 13, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213858714701135

(18) Wang, T.J., et al. (2008). Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation, 117(4), 503-511. Accessed Apr 19, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127

(19) Cutolo, M., et al. (2007). Vitamin D in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmunity Reviews, 7(1), 59-64. Accessed Apr 13, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1568997207001140

(20) Haykal, T., et al. (2019). The role of vitamin D supplementation for primary prevention of cancer: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, 9(6), 480-488. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20009666.2019.1701839

(21) Chakraborti, C.K. (2011). Vitamin D as a promising anticancer agent. Indian journal of pharmacology, 43(2), 113-120. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3081446/

(22) Sadat-Ali, M., et al. (2014). Topical delivery of vitamin d3: a randomized controlled pilot study. International journal of biomedical science : IJBS, 10(1), 21-24. Accessed Apr 20, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3976443/

(23) Elham, A.S., et al. (2021). Serum vitamin D, calcium, and zinc levels in patients with COVID-19. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, 43, 276-282. Accessed May 16, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405457721001431

(24) Lee, J., O. van Hecke, and N. Roberts. (2020). Vitamin D: A rapid review of the evidence for treatment or prevention in COVID-19. The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Accessed Apr 20, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/vitamin-d-a-rapid-review-of-the-evidence-for-treatment-or-prevention-in-covid-19/

(25) Macdonald, H.M., et al. (2011). Sunlight and dietary contributions to the seasonal vitamin D status of cohorts of healthy postmenopausal women living at northerly latitudes: a major cause for concern? Osteoporos Int, 22(9), 2461-2472. Accessed Apr 17, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6365669/

(26) U.S Department of Agriculture and Agricultural Research Service, FoodData Central. Accessed Apr 17, 2022. Retrieved from https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/index.html

(27) Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council and Ministry of Health. (Sept 22, 2017). Introduction. Accessed Apr 16, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.nrv.gov.au/introduction

(28) National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and New Zealand Ministry of Health. (2020). Vitamin D. Accessed Apr 12, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients/vitamin-d

(29) Mulligan, G.B. and A. Licata. (2010). Taking vitamin D with the largest meal improves absorption and results in higher serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Bone Miner Res, 25(4), 928-930. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://asbmr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jbmr.67

(30) Dawson-Hughes, B., et al. (2015). Dietary fat increases vitamin D-3 absorption. J Acad Nutr Diet, 115(2), 225-230. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212267214014683?via%3Dihub

(31) Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A., et al. (2012). A Pooled Analysis of Vitamin D Dose Requirements for Fracture Prevention. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(1), 40-49. Accessed May 15, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1109617

(32) Nowak, A., et al. (2016). Effect of vitamin D3 on self-perceived fatigue: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Medicine, 95(52), e5353. Accessed Apr 20, 2022. Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/fulltext/2016/12300/effect_of_vitamin_d3_on_self_perceived_fatigue__a.2.aspx

(33) Wicherts, I.S., et al. (2007). Vitamin D Status Predicts Physical Performance and Its Decline in Older Persons. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 92(6), 2058-2065. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/92/6/2058/2597231

(34) Menon, V., et al. (2020). Vitamin D and Depression: A Critical Appraisal of the Evidence and Future Directions. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 42(1), 11-21. Accessed Apr 19, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6970300/

(35) Gurley, B.J., et al. (2018). Clinically Relevant Herb-Micronutrient Interactions: When Botanicals, Minerals, and Vitamins Collide. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 9(4), 524S-532S. Accessed Apr 16, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6054245/

(36) DeNoon, D.J. (2009). Vitamin D: Drug Interactions. WebMD. Accessed Apr 16, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/osteoporosis/features/the-truth-about-vitamin-d-drug-interactions

(37) Saini, K. and V. Mysore. (2021). Role of vitamin D in hair loss: A short review. J Cosmet Dermatol, 20(11), 3407-3414. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jocd.14421

(38) Romano, F., et al. (2020). Vitamin D and Sleep Regulation: Is there a Role for Vitamin D? Curr Pharm Des, 26(21), 2492-2496. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32156230/

(39) Choi, J.H., et al. (2020). Relationship between Sleep Duration, Sun Exposure, and Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Status: A Cross-sectional Study. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 4168. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-61061-8#citeas

(40) Larsen, A.U., et al. (2021). No improvement of sleep from vitamin D supplementation: insights from a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Medicine: X, 3, 100040. Accessed Apr 18, 2022. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590142721000094