Zohreh Doborjeh

(PhD (Cognitive Neuroscience), BS and MS (Psychology), Cert (Neuroinformatics), Certified Mindfulness Facilitator)

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is crucial for brain health and reducing the risk of neurological disorders.

Research indicates that many cognitive issues prevalent today are linked to lifestyle choices, including:

- diet

- sleep patterns

- stress management

- physical

- mental activities

Among these factors, regular exercise stands out for its profound impact on brain health. Research increasingly supports the positive effects of both physical and mental exercises on brain health.

The Connection Between Physical Activity and Brain Health

Physical exercise is a powerful tool for enhancing brain structure and function. It increases blood oxygen levels, which are vital for maintaining optimal brain health and function.

Regular physical activity promotes the release of neurotrophic factors that support neuron survival and the growth of new synapses, improving brain functions and reducing the risk of cognitive decline.[1]

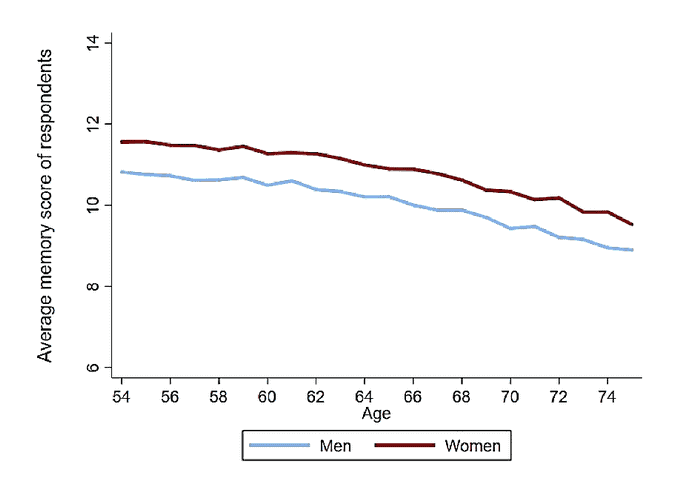

Longitudinal studies on aging populations showed that age-related declines in memory are observed in both genders, with men experiencing a slower decline.

Men experience a slower decline in memory

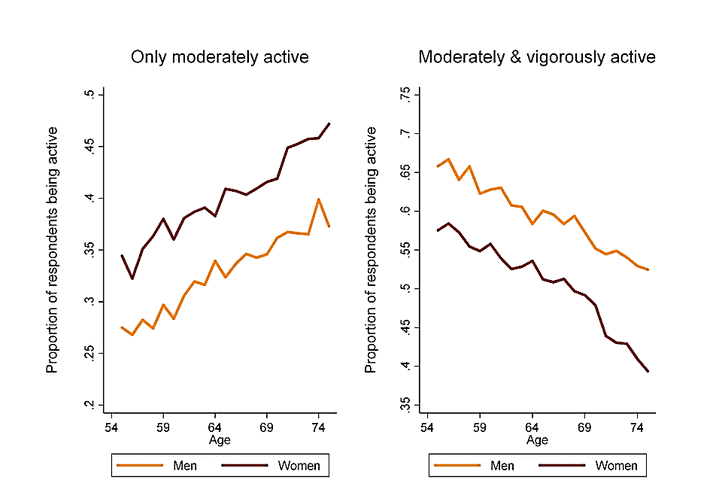

Research conducted by the University of Queensland, Australia, revealed that engaging in moderate to vigorous physical activity at least once a week can enhance memory.

Weekly moderate exercise improved cognitive function by an average of 5% in men and 14% in women.[2]

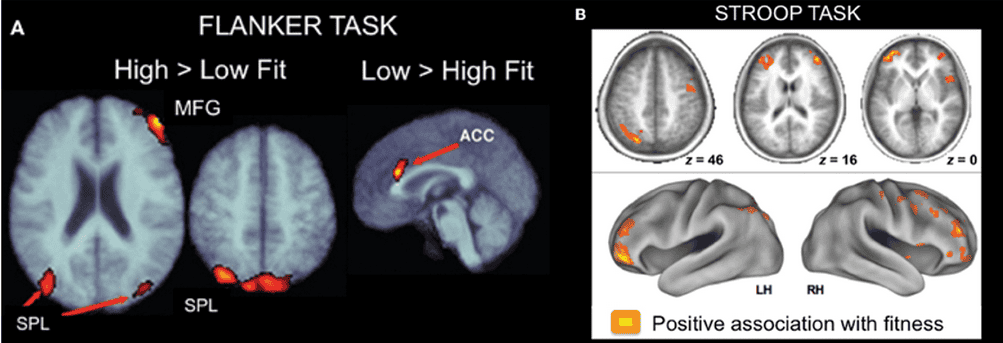

Recent structural (sMRI) and functional (fMRI) Magnetic Resonance Imaging studies have shown a positive link between physical activity and improved brain function and structure. This is evidenced by the positive association between physical activity and enhanced brain activity across various cognitive tasks.[3]

(A) Increased activation in the lateral fronto-parietal regions and reduced activation in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) during a flanker task in older adults as a function of fitness;

(B) Increased activation in the lateral fronto-parietal regions during a Stroop task as a function of aerobic exercise.

Flanker Task assesses the ability to focus on a central target while ignoring surrounding distractions, measuring attention and interference control.

Stroop Task assesses the ability to handle conflicting information; where you name the ink color of a word that spells a different color.

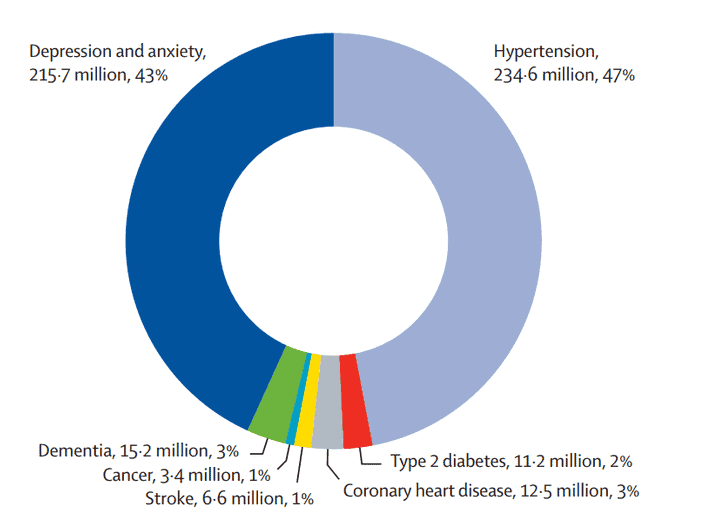

One in 4 adults and 4 in 5 adolescents don’t do enough physical activity. The World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that nearly 500 million new cases of preventable non-communicable diseases (NCDs) could arise globally by 2030 if physical inactivity continues at current levels.

Out of these new cases, 234.6 million (47%) would be related to hypertension, 215.7 million (43%) would be attributed to depression and anxiety, and 15.2 million (3%) would be due to dementia.[4]

With this knowledge, it becomes clear that maintaining physical activity is crucial, especially for older adults.

Now, the question is: what types of exercises are most effective for achieving these cognitive benefits?

Types of Physical Exercises That Benefit Brain Health

Different types of exercises provide unique benefits for the brain. By categorising them into cardio exercises, strength training, and flexibility and balance exercises, we can better understand how each type contributes to brain health.

- Cardio exercises increase heart rate and blood flow, enhancing oxygen delivery to the brain and promoting neurogenesis.

- Strength training builds muscle and increases growth factors that support neuronal health.

- Flexibility and balance exercises reduce stress and promote relaxation, improving cognitive performance and emotional well-being.

Cardio Exercises

Cardiovascular exercises involve activities that raise heart rate and enhance blood flow throughout the body. These exercises are beneficial for brain health because they increase oxygen delivery to the brain, which supports neurogenesis in the hippocampus, improving cognitive functions such as:

- focus

- memory

- attention

- mood regulation[5]

Examples include running, swimming, and cycling.

Swimming has been shown to benefit children with ADHD

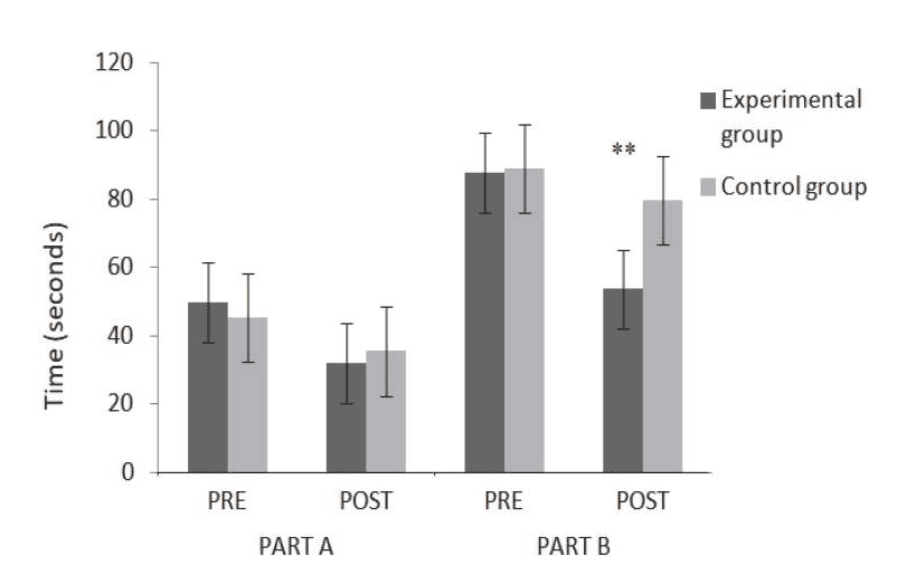

In a 2022 study the impact of a 12-week swimming programme on cognitive tasks, disruptive behaviour, and academic performance in children with ADHD was explored.[6]

The results showed significant improvements in the ADHD group compared to the control group. Specifically, in the Hayling test—a measure of cognitive flexibility and inhibition with two parts:

- Part A (response initiation) showed a 32.34% decrease in latency time

- Part B (response inhibition) showed a 41.66% decrease in latency time

These findings suggest that the swimming intervention effectively enhanced cognitive control and reduced the time needed to respond and inhibit inappropriate responses in ADHD children.

Additionally, academic performance improved, with significant increases in reading comprehension and math scores post-intervention.

Part A and B latency times decreased significantly in the experimental (ADHD) group.

Part A showing a 32.34% reduction and Part B a 41.66% reduction, highlighting the effectiveness of swimming on inhibitory control and task execution speed.

No significant changes were observed in the control group.

The ADHD group also showed a marked increase in maximum oxygen consumption, further supporting the potential of swimming to foster neural growth and cognitive development.[6,7]

Strength Training

Strength training exercises focus on building muscle mass and strength through activities like weightlifting and resistance exercises.[8]

These exercises contribute to brain health by increasing levels of growth factors that support neuronal health.[9]

Engaging in strength training can also:

- reduce anxiety

- improve cognition

- alleviate symptoms of depression[10]

Research highlights numerous mental health benefits associated with strength training, including enhanced self-esteem and better sleep patterns.[11,12]

RELATED — Great Sleep means Great Health: 17 Health Benefits of Good Sleep

Strength training has been shown to improve cognitive function in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

A study from the University of Sydney found that six months of strength training can protect brain areas susceptible to Alzheimer’s disease.

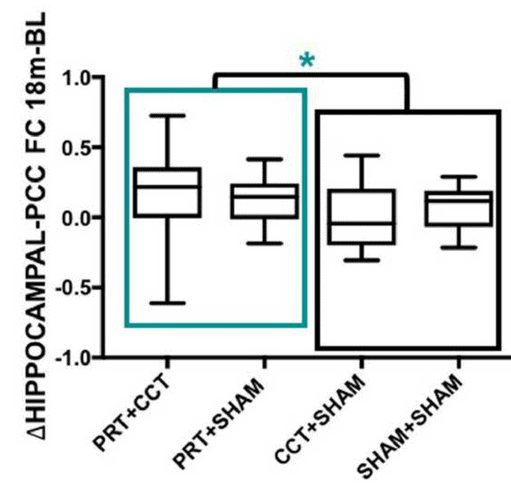

This study investigated the effects of progressive resistance training (PRT) on early Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and over a 6-month period the researchers observed a 1.2% increase in hippocampal volume and a 10% improvement in functional connectivity between the hippocampus and posterior cingulate cortex.[13]

Participants were randomized into one of four groups: combined progressive resistance training and computerized cognitive training (PRT+CCT), progressive resistance training and cognitive sham (PRT+SHAM), computerized cognitive training and sham exercise (CCT+SHAM), and sham exercise with cognitive sham (SHAM+SHAM).

The results showed a significant increase in connectivity for the groups that participated in resistance training (PRT+CCT and PRT+SHAM) compared to those that did not (CCT+SHAM and SHAM+SHAM).

Another study links muscle strength to a reduced risk of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. A study of 900 older adults at Rush University found that, over 3.6 years, each 1-unit increase in muscle strength was associated with a 43% lower risk of AD and a 33% lower risk of MCI.

Additionally, greater muscle strength correlated with slower cognitive decline, suggesting its importance in reducing the risk of dementia in older age.[14]

Flexibility and Balance Exercises

Flexibility and balance exercises aim to improve range of motion, stability, and relaxation.[15] Practices such as yoga and tai chi are particularly noted for their benefits to brain health.

These exercises reduce stress levels and promote relaxation, which can lower cortisol production and improve cognitive performance.[16,17]

By calming the mind and body, yoga enhances cognitive performance, including improvements in working memory, mental flexibility, and attention span.[18]

Research indicates that yoga may have neuroprotective effects by activating areas of the brain susceptible to age-related decline, potentially reducing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.[18]

This practice’s ability to promote neuroplasticity further underscores its benefits for maintaining brain health. Yoga can also contribute to well-being by fostering mood regulation and reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression.[19]

Integrating flexibility and balance exercises into daily routines can provide comprehensive benefits for both physical and mental well-being.

Exercising Outdoors: A Superior Boost for Brain Health

The environment where we exercise can significantly impact brain health.

Spending time in nature boosts cognitive function

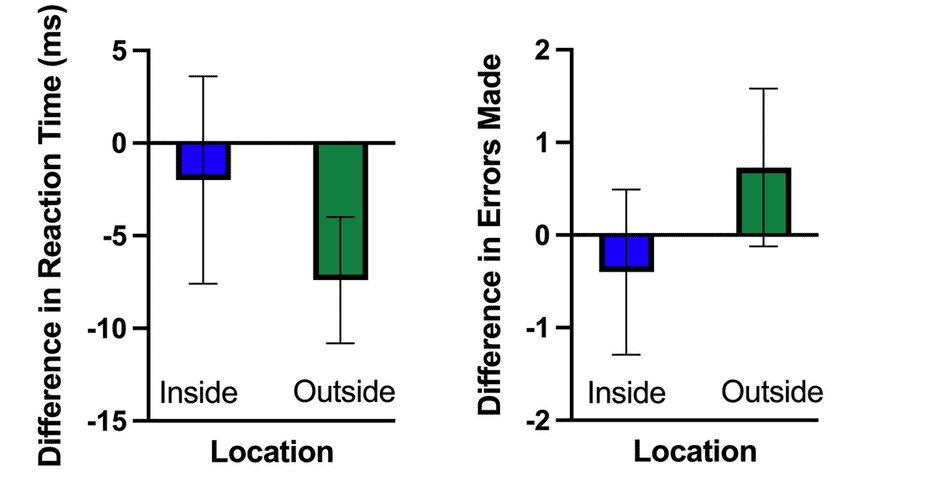

Combining outdoor time with exercise may provide even greater brain benefits. In a study, EEG data showed improved attention and working memory after a 15-minute outdoor walk, but not after an indoor walk.[20]

Value on plot = post walk score − pre-walk score. Therefore, negative values indicate improved performance.

This suggests that being outdoors may enhance cognitive function more than exercise alone, emphasising the importance of outdoor activities, especially with increasing urbanisation and indoor sedentary lifestyles.

Related Questions

1.What does exercise addiction do to the brain?

Exercise addiction disrupts dopamine balance, reducing pleasure from other activities and causing dependence on exercise for mood regulation.

Maintaining a healthy exercise balance is crucial.

2. Does exercise rewire our brain?

Exercise rewires the brain by promoting neurogenesis (the creation of new neurons) and synaptic plasticity (the strength of connections between neurons), enhancing memory, learning, and cognitive function, and helping maintain mental health across all ages.

3. What is the minimum amount of physical exercise daily that will have a positive effect on my mood and brain health?

The optimal amount of daily exercise varies based on individual factors such as age, overall well-being, and fitness level.

Aim for 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise daily. Gradual increase ensures long-term benefits for mood and brain health.

For more similar articles, please see our Brain Health section.

Zohreh is a Senior research fellow and lecturer, holding Master’s and Bachelor’s degrees with Honors in Psychology, and a Ph.D. in Cognitive Neuroscience. She has eight years of research and teaching experience in the subjects of psychology, neuroscience, and Neuroinformatics across different universities in New Zealand, including the University of Auckland, Auckland University of Technology, and The University of Waikato.

If you would like to learn more about Zohreh , see Expert: Zohreh Doborjeh.

References

(1) Gomez-Pinilla, F., & Hillman, C. (2013). The influence of exercise on cognitive abilities. Comprehensive Physiology, 3(1), 403.

(2) Lenzen, S., Gannon, B., & Rose, C. (2020). A dynamic microeconomic analysis of the impact of physical activity on cognition among older people. Economics & Human Biology, 39, 100933.

(3) Colcombe, S. J., Kramer, A. F., Erickson, K. I., Scalf, P., McAuley, E., Cohen, N. J., … & Elavsky, S. (2004). Cardiovascular fitness, cortical plasticity, and aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(9), 3316-3321.

(4) Santos, A. C., Willumsen, J., Meheus, F., Ilbawi, A., & Bull, F. C. (2023). The cost of inaction on physical inactivity to public health-care systems: a population-attributable fraction analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 11(1), e32-e39. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9748301/

(5) Thomas, A. G., Dennis, A., Bandettini, P. A., & Johansen-Berg, H. (2012). The effects of aerobic activity on brain structure. Frontiers in psychology, 3, 86. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00086/full

(6) Shoemaker, L. N., Wilson, L. C., Lucas, S. J., Machado, L., Thomas, K. N., & Cotter, J. D. (2019). Swimming‐related effects on cerebrovascular and cognitive function. Physiological reports, 7(20), e14247.

(7) Hattabi, S., Forte, P., Kukic, F., Bouden, A., Have, M., Chtourou, H., & Sortwell, A. (2022). A randomised trial of a swimming-based alternative treatment for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16238.

(8) Brown, L. E. (2007). Strength training. Human Kinetics.

(9) Goekint, M., De Pauw, K., Roelands, B., Njemini, R., Bautmans, I., Mets, T., & Meeusen, R. (2010). Strength training does not influence serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor. European journal of applied physiology, 110, 285-293.

(10) O’Connor, P. J., Herring, M. P., & Caravalho, A. (2010). Mental health benefits of strength training in adults. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 4(5), 377-396.

(11) Mikkelsen, K., Stojanovska, L., Polenakovic, M., Bosevski, M., & Apostolopoulos, V. (2017). Exercise and mental health. Maturitas, 106, 48-56.

(12) Kline, C. E. (2014). The bidirectional relationship between exercise and sleep: implications for exercise adherence and sleep improvement. American journal of lifestyle medicine, 8(6), 375-379. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4341978/

(13) Broadhouse, K. M., Singh, M. F., Suo, C., Gates, N., Wen, W., Brodaty, H., … & Valenzuela, M. J. (2020). Hippocampal plasticity underpins long-term cognitive gains from resistance exercise in MCI. NeuroImage: Clinical, 25, 102182.

(14) Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Wilson, R. S., Leurgans, S. E., & Bennett, D. A. (2009). Association of muscle strength with the risk of Alzheimer disease and the rate of cognitive decline in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of neurology, 66(11), 1339-1344.

(15) Hwang, H., & Koo, J. (2019). Effects of stretching exercises and core muscle exercises on flexibility and balance ability. Journal of international academy of physical therapy research, 10(1), 1717-1724.

(16) Zhou, M., Liao, H., Sreepada, L. P., Ladner, J. R., Balschi, J. A., & Lin, A. P. (2018). Tai Chi improves brain metabolism and muscle energetics in older adults. Journal of Neuroimaging, 28(4), 359-364.

(17) Desai, R., Tailor, A., & Bhatt, T. (2015). Effects of yoga on brain waves and structural activation: A review. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 21(2), 112-118.

(18) Krause-Sorio, B., Siddarth, P., Kilpatrick, L., Milillo, M. M., Aguilar-Faustino, Y., Ercoli, L., … & Lavretsky, H. (2022). Yoga prevents gray matter atrophy in women at risk for Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 87(2), 569-581.

(19) Riley, K. E., & Park, C. L. (2015). How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry. Health psychology review, 9(3), 379-396.

(20) Boere, K., Lloyd, K., Binsted, G., & Krigolson, O. E. (2023). Exercising is good for the brain, but exercising outside is potentially better. Scientific reports, 13(1), 1-8. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-26093-2