Zohreh Doborjeh

(PhD (Cognitive Neuroscience), BS and MS (Psychology), Cert (Neuroinformatics), Certified Mindfulness Facilitator)

Brain health is not often talked about, because the brain doesn’t have the ability to hurt or cause physical pain, apart from occasional migraines and headaches.

That is why we only act once there are visible signs of neurodegeneration, and by that time it might be too late to prevent or reverse the condition.

In this article, we will look into the topic of:

- brain

- brain health

- neurodegenerative diseases

and set the stage for subsequent articles on how to keep our brain healthy and young, despite our chronological age.

What is the Brain?

The brain is the most complex organ that controls bodily functions, shapes thoughts, emotions, and behaviours in a continuous interplay with the world around us.[1]

The brain is about 60% fat, with the remaining percentage consisting of proteins, carbohydrates, various minerals and water.

The brain, despite being just two percent of our body weight, consumes 20 percent of the body’s total energy.[1]

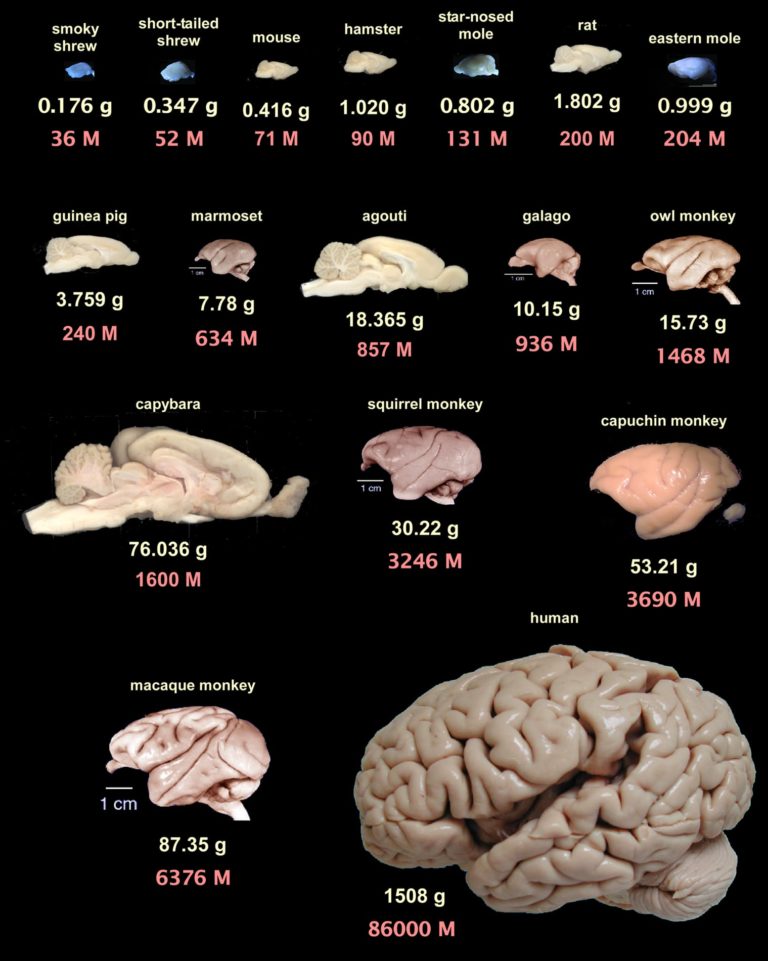

The fundamental units of the brain are neurons, totalling around one hundred billion.[2] These specialised cells transmit information through a complex network of electrical and chemical signals.[2]

The structure of the brain

Structurally, the brain can be categorised into three main regions, which are:

- Cerebrum

- Brainstem

- Cerebellum[3]

The cerebrum consists of two cerebral hemispheres, each nearly symmetrical and divided into left and right hemispheres by a deep groove.

Each hemisphere is responsible for controlling the opposite side of the body, with the right hemisphere controlling the left side and vice versa.

The left hemisphere is known as the categorical hemisphere, specialising in spoken and written language, as well as sequential and analytical reasoning, including math and science.

The right hemisphere is the representational hemisphere, focusing on the perception of spatial relationships, patterns, music, face recognition, and artistic skills.[3,4]

Each brain hemisphere is responsible for controlling the opposite side of the body

The cerebellum contains about 50% of the brain’s neurons (69 billion out of 89 billion), and is mainly for body position, balance, and fine motor control.[5]

The brainstem controls various vital functions, consisting of the medulla for physiological needs, pons for safety (especially eye movements during REM sleep), and midbrain for processing fight-or-flight responses to stimuli. It’s a crucial hub that connects the brain to the spinal cord.[1]

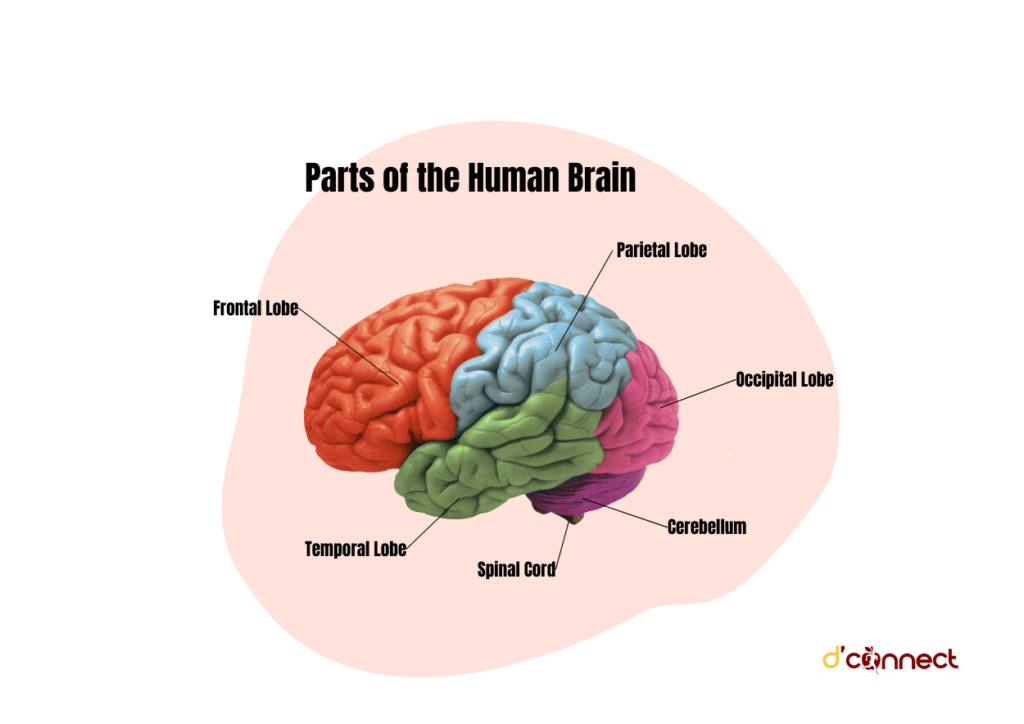

Both hemispheres are further divided into four lobes: the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe. Each lobe plays a distinct role in various cognitive functions, contributing to the brain’s overall complexity and functionality.[1]

The frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is located at the front of the cerebrum, and is the largest among the four lobes of the cerebral cortex.

It is primarily responsible for:

- voluntary movement

- speech production

- decision making

- planning

- learning

- attention

Several crucial systems or pathways contribute to frontal lobe functioning. These include:

- Primary motor cortex (controls voluntary movement)

- Broca’s area (language processing)

- Prefrontal cortex (responsible for executive functions, dopamine pathway, which influences reward seeking behaviour)

Parietal lobe

Located posterior to the central sulcus and is responsible for processing sensory information, spatial orientation, and language.

Within the parietal lobe, the somatosensory cortex is the hub for receiving and processing sensory information from the body, enabling us to interpret the world around us.

Temporal lobe

The temporal lobe is located on the sides of the brain, beneath the lateral fissure. The temporal lobe is involved in various functions, including auditory information processing, memory, emotion, and object identification.

Within the temporal lobe, Wernicke’s area, located in the left hemisphere, is essential for language comprehension. Additionally, the limbic system, comprising structures like the amygdala and hippocampus, collaborates across different brain regions to regulate emotions and memory.

Occipital lobe

Lastly, the occipital lobe, located at the back of the brain and above the cerebellum. Within the occipital lobe is the visual cortex that is primarily functioning for visual information processing.[1]

The occipital lobe plays a crucial role in detecting visual stimuli, contributing to conscious awareness and processing visual information related to size, shape, colour, and motion.

Another significant function of the occipital lobe is recognising visual stimuli through What (identification) and Where (location) pathways, matching incoming visual information with stored mental representations.

Understanding the brain’s structure and function is key to appreciating its remarkable capabilities and the importance of maintaining its health.

How do we define brain health?

Traditional perspectives on brain health have often centred around the medical model, emphasising disease, disorders, and deficits.

However, brain health definition extends beyond these parameters. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has defined brain health as the promotion of optimal brain development, cognitive health, and well-being across the life course.[6]

Among all human systems, the human brain has the greatest potential for enhancement and rewiring.

Over the past thirty years, research in cognitive neuroscience has broadened the definition of brain health to three key elements:

- Clarity

- Connectedness

- Emotional Balance[7]

Clarity involves the ability to think deeply and strategically, optimising and fostering the creation of new opportunities and solutions.

Connectedness pertains to one’s capacity to enjoy fulfilling experiences and maintain meaningful life and relationships.

Emotional Balance involves facing difficult situations and handling adversity while remaining productive and capable.[8]

This broader view emphasises the ever-changing aspect of brain health and the many different ways we can work towards enhancing it.

Brain disorders and diseases

The term “brain disorders” covers a broad range of conditions that affect the structure or function of the brain, resulting in changes to cognition, social, emotion, and physical abilities.

Brain disorders are caused by varying factors such as:

- genetics

- developmental problems

- trauma

- infections

- degenerative processes

Brain disorders can be categorised based on their characteristics, underlying causes, and the specific brain regions affected.[9,10] Some common categories of brain disorders include:

- Neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, which result in the progressive loss of brain cells and cognitive function.

- Neurodevelopmental diseases, such as autism and ADHD, which affect the development and function of the brain during childhood and adolescence.

- Cerebrovascular disorders, including stroke, which occur when blood flow to the brain is interrupted or reduced.

- Traumatic brain injuries, which can result from physical trauma to the head or body.

- Mental or psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder, which affect mood, thought processes, and behaviour.

RELATED — Introduction to: Depression

Category | Health Conditions / Disease |

Neurodegenerative Disorders | Alzheimer, Parkinson, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia |

Mental or Psychiatric Disorders | Depression, Anxiety, Schizophrenia |

Neurodevelopmental Disorders | Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD, Brain malformations, Cerebral palsy, Foetal alcohol syndrome |

Cerebrovascular Disorders | Stroke |

Traumatic Brain Injury | Concussion, Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) |

Infectious Diseases | Encephalitis, Meningitis |

Genetic Disorders | Huntington’s Disease, Down Syndrome, Batten Disease |

Movement Disorders | Ataxia, Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s Disease, Stroke, Motor Neuron Disease, Neuropathy |

Sensory Systems and Disorders | Balance Disorders, Epilepsy, Pain, Tinnitus |

Please note that the information in the table is a general overview of the conditions.

Brain disorders and diseases worldwide and in New Zealand

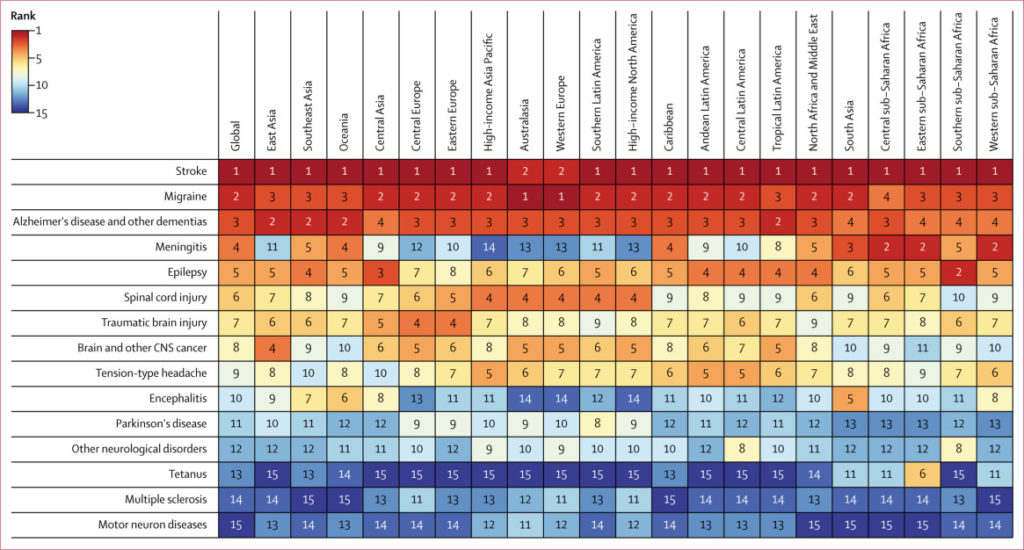

Neurological disorders are currently the second leading cause of death and the primary contributor to global disability.

According to a recent Global Burden of Disease (GBD), the number of individuals living with brain-related diseases is projected to double by 2050.[11,12,13]

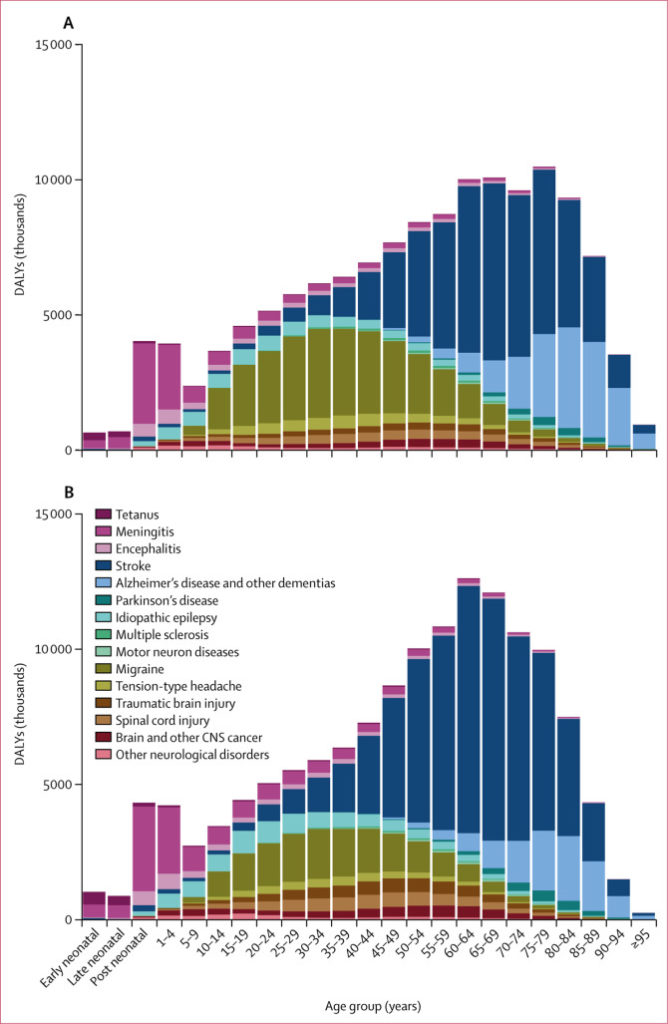

In 2016, the top five contributors to neurological causes of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) on a global scale were:

- stroke (42.2%)

- headaches (migraine, 16.3%)

- dementias (10.4%)

- meningitis (7.9%)

- epilepsy (4.9%)[14]

In New Zealand, the impact of brain disorders is significant, with projections indicating that by 2036, one in four New Zealanders aged over 65 will be affected by such conditions.

According to the GBD study, prevalent disorders include Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Motor Neuron disease, and Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBIs).

The Motor Neuron disease mortality rate is recorded at 2.2 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, surpassing figures in Australia and the United Kingdom.

One in four Kiwis aged 65 and over will be affected by a brain disorder

The prevalence of Parkinson’s has risen from 7000 in 2006 to over 11,000 currently, with an anticipated doubling by 2040.[15]

Traumatic brain injuries are also a common cause of hospital admissions in New Zealand, with a total incidence of 790 cases per 100,000 persons. Among these, 749 cases per 100,000 persons involved mild TBIs, while 41 cases per 100,000 persons pertain to moderate to severe TBIs.[16]

Early neonatal is 0–7 days; late neonatal is 7–28 days; and post-neonatal is 28 days to 1 year. (A) Females. (B) Males.

These statistics underscore the importance of ongoing research, public awareness, and effective healthcare strategies to address the growing impact of brain disorders and diseases on individuals and communities worldwide, as well as in New Zealand.

How to keep your brain healthy

Investing in brain health secures our future. Constant care and nourishment maintain the brain’s agility and resilience. We’re not bound by genetics as neuroscientific findings highlight our adaptability.

This is the prime time for us to reduce the burden of mental and neurological disorders and address challenges for the preservation of brain health. We have the power, and achieving optimal brain health is just one decision away.

Sleep and brain health

Quality sleep is necessary for the brain to facilitate memory consolidation, emotional regulation, and cognitive function. During sleep, the brain clears toxins, including beta-amyloid, a protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease, accumulated during waking hours, promoting optimal neural functioning.[17]

RELATED — Why we sleep: The role of sleep in our healthy life

Relaxation and brain health

Stress is a part of our life, but excessive stress can impair brain functions. Regular relaxation practices such as breathwork, meditation, mindfulness, and yoga can regulate and reduce the impact of stress hormones like cortisol on both the body and brain.[18,19,20]

RELATED — Introduction to Mindfulness: Enjoy the present moment and appreciate life

Exercise and neuroplasticity

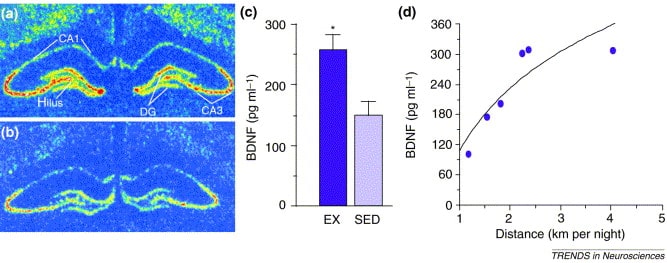

Physical activity is linked to a lower risk of neurodegenerative diseases. Exercise enhances blood flow, promotes the growth of new neurons, and reduces stress. It supports cognitive function, memory, and mood.[21]

RELATED — Understanding Stress: The Silent Killer

Diet for a healthy brain

A well-balanced diet is linked to a lower risk of cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disorders. Including a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats provides essential components for brain nourishment. Incorporating complex carbohydrates like blueberries, often referred to as “brain berries,” enhances memory and attention. Additionally, maintaining proper hydration is vital for optimal brain performance.[22]

RELATED — The Healthy Plate Model: Essentials of Healthy Eating

Also, important to mention are the benefits of a ketogenic diet, as some studies have reported improvements in cognitive function, memory, and attention in individuals and treatment of seizure, epilepsy, and mood disorders.

Social connection

This includes interactions with family, friends, and communities. Positive social interactions have several benefits on emotional well-being, brain plasticity, cognitive stimulation, and stress reduction.[23]

Medical checks

Regular health examinations can help in early detection and management of conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and depression.

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

For example, monitoring key health indicators, including cholesterol levels will contribute to maintaining an optimal cognitive function and reducing the risk of cognitive decline.

Related Questions

1. What is brain fog?

Brain fog is a condition characterised by inability with concentration, difficulty in information processing, confusion, and disorientation.

Brain fog is not classified as a medical or psychiatric disorder, but is a symptom associated with other problems such as Covid-19, ADHD, depression, and dementia.

2. What is the best breakfast for the brain?

The brain-boosting breakfast includes proteins and healthy fats.

Foods like eggs, yoghurt, nuts, and avocado can support cognitive function and sustained energy.

RELATED — Everything You Need to Know When Buying Eggs (Part 1)

3. What’s the worst habit for brain health?

The most damaging habits for the brain include heavy alcohol consumption, smoking, caffeine and sugar intake.

RELATED — Diet and the Brain: Our brain on sugar

Additionally, lifestyle patterns such as automatic negative thoughts, feelings of loneliness and isolation, inadequate sleep, and too much screen time contribute to cognitive health risks.

If you have any questions, or suggestions please let us know in the comment section below.

Zohreh is a Senior research fellow and lecturer, holding Master’s and Bachelor’s degrees with Honors in Psychology, and a Ph.D. in Cognitive Neuroscience. She has eight years of research and teaching experience in the subjects of psychology, neuroscience, and Neuroinformatics across different universities in New Zealand, including the University of Auckland, Auckland University of Technology, and The University of Waikato.

Her research interests are early diagnosis and prognosis of mental health issues and suggesting personalized interventions with respect to integration of neuroimaging, genetic, behavioural, social, and cognitive datasets.

Since 2015, she has been managing the Electroencephalography (EEG) lab at KEDRI Institute, leading cognitive neuroscience-based projects that delved into the complexities of brain dynamics and mental health informatics.

Zohreh is a Co-Founder of the Neuroinformatics Research Society in New Zealand and acts as the co- leader of the Neuroinformatics theme at KEDRI/AUT.

Recently, Zohreh expanded her expertise by becoming a Mindfulness Facilitator, providing personalized mindfulness programs and contributing valuable insights for future research.

References:

(1) Carter, R. (2019). The brain book: An illustrated guide to its structure, functions, and disorders. (Dorling Kindersley Ltd).

(2) Herculano-Houzel, S. (2009). The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 31. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.031.2009

(3) Nowinski, W. L. (2011). Introduction to brain anatomy. Biomechanics of the Brain, 5-40.

(4) Rhoton Jr, A. L. (2007). The cerebrum. Neurosurgery, 61(1), SHC-37.

(5) Glickstein, M. (2007). What does the cerebellum really do? Current Biology, 17(19), R824-R827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.009

(6) World Health Organisation. (2022). Optimising brain health across the life course: WHO position paper.

(7) Zientz, J., Spence, J. S., Chung, S. S. E., Nanda, U., & Chapman, S. B. (2023). Exploring how brain health strategy training informs the future of work. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1175652

(8) Bradley, K. L., Goetz, T., & Viswanathan, S. (2018). Toward a contemporary definition of health. Military medicine, 183(suppl_3), 204-207. https://academic.oup.com/milmed/article/183/suppl_3/204/5194600

(9) Cooper, R. (2018). Diagnosing the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Routledge.

(10) Sachdev, P. S., Blacker, D., Blazer, D. G., Ganguli, M., Jeste, D. V., Paulsen, J. S., & Petersen, R. C. (2014). Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach. Nature Reviews Neurology, 10(11), 634-642.

(11) Feigin, V. L., Owolabi, M. O., Abd-Allah, F., Akinyemi, R. O., Bhattacharjee, N. V., Brainin, M., … & Liebeskind, D. S. (2023). Pragmatic solutions to reduce the global burden of stroke: a World Stroke Organisation–Lancet Neurology Commission. The Lancet Neurology, 22(12), 1160-1206. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00277-6

(12) Feigin, V. L., Vos, T., Nichols, E., Owolabi, M. O., Carroll, W. M., Dichgans, M., … & Murray, C. (2020). The global burden of neurological disorders: translating evidence into policy. The Lancet Neurology, 19(3), 255-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30411-9

(13) World Health Organisation. (2023). Intersectoral global action plan on Epilepsy and other neurological disorders 2022–2031.

(14) Feigin, V. L., Nichols, E., Alam, T., Bannick, M. S., Beghi, E., Blake, N., … & Fischer, F. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology, 18(5), 459-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X

(15) MacAskill, M. R., Pitcher, T. L., Melzer, T. R., Myall, D. J., Horne, K. L., Shoorangiz, R., … & Anderson, T. J. (2023). The New Zealand Parkinson’s progression programme. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 53(4), 466-488.

(16) Feigin, V. L. et al. Incidence of traumatic brain injury in New Zealand: a population-based study. The Lancet Neurology 12, 53-64 (2013).

(17) Nedergaard, M. Is Your Brain Clearing Beta-Amyloid, the Leading Cause of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s?

(18) Aguilar‐Raab, C., Stoffel, M., Hernández, C., Rahn, S., Moessner, M., Steinhilber, B., & Ditzen, B. (2021). Effects of a mindfulness‐based intervention on mindfulness, stress, salivary alpha‐amylase and cortisol in everyday life. Psychophysiology, 58(12), e13937. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13937

(19) Pascoe, M. C., Thompson, D. R., & Ski, C. F. (2017). Yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and stress-related physiological measures: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 86, 152-168.

(20) Fincham, G. W., Strauss, C., Montero-Marin, J., & Cavanagh, K. (2023). Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 432. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27247-y

(21) Cotman, C. W., & Berchtold, N. C. (2002). Exercise: a behavioural intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends in neurosciences, 25(6), 295-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02143-4

(22) Gómez-Pinilla, F. (2008). Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nature reviews neuroscience, 9(7), 568-578.

(23) Eisenberger, N. I., & Cole, S. W. (2012). Social neuroscience and health: neurophysiological mechanisms linking social ties with physical health. Nature neuroscience, 15(5), 669-674.