Bernadeth Atrinindarti

MAppSc (Advanced Nutrition Practice)

Jump to:

- What is Copper?

- Copper deficiency

- Different types of Copper

- Health Benefits

- Health Claims

- Best sources of Copper

- Daily requirements and intake

- How to take Copper

- Signs and symptoms of deficiency

- Risks and side effects

- Interactions - herbs and supplements

- Interactions - medication

- Summary

- Related Questions

When it comes to our general health and wellbeing, copper is not often mentioned. However, copper is found in all body tissues and is an important micronutrient that assist with:

- Anemia

- Hypopigmentation

- Elevated cholesterol levels

- Connective tissue disorders

- Osteoporosis and other bone defects

Though copper deficiency is rare, there are certain minerals that compete with copper for absorption, which we’ll also look into in this article.

What is Copper?

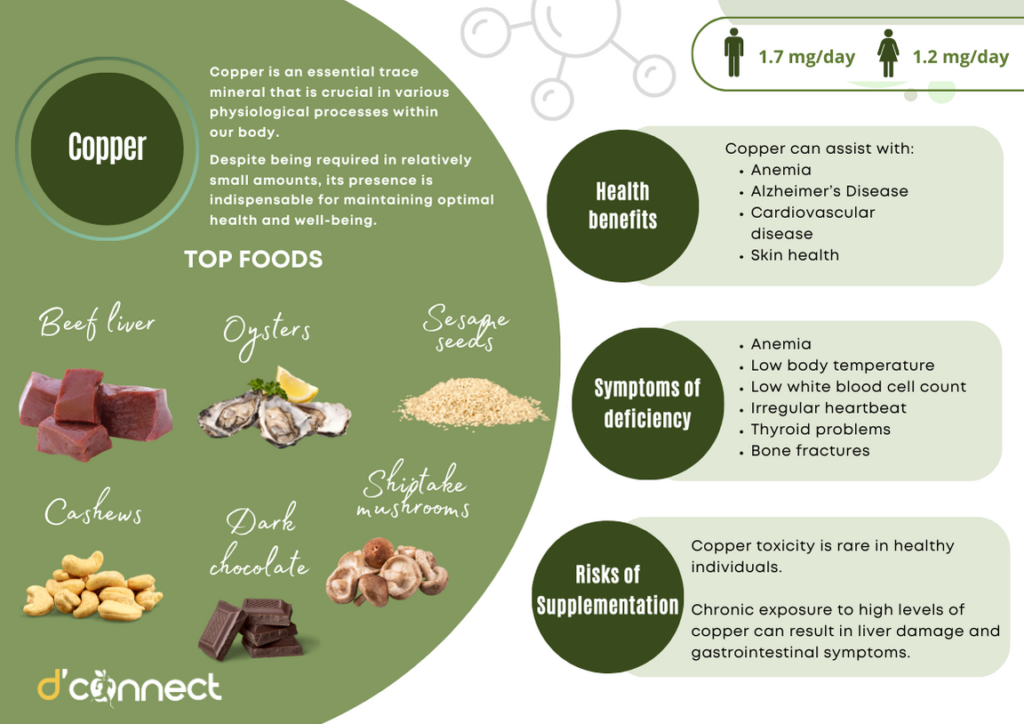

Copper is an essential trace mineral that is crucial in various physiological processes within our body. Despite being required in relatively small amounts, its presence is indispensable for maintaining optimal health and well-being.

Copper is a cofactor for several enzymes, known as cuproenzymes, which are involved in:

- Energy production

- Iron metabolism

- Neuropeptide activation

- Connective tissue synthesis

- Neurotransmitter synthesis

Only small amounts of copper are typically stored in the body and the average adult has a total content of 50-120mg. Most copper is excreted in bile, and a small amount is excreted in urine.

Our body can only store 50-120mg of copper

The discovery of copper as an essential nutrient

In the 1920s, a group of University of Wisconsin chemists, led by Dr. E. B. Hart, found that copper has an essential role in human nutrition and livestock feeding. Wisconsin researchers found that adequate copper plays an important role in a condition similar to anemia in children.

The condition was caused by a shortage of iron, which was reported depending on the absence and presence of copper.[1]

Later in the 1960s, the importance of copper for humans was first shown in malnourished children from Peru.

These children had anemia refractory to iron therapy, neutropenia, and bone abnormalities that were responsive to copper supplementation.

Copper deficiency

Copper deficiency is a rare and isolated phenomenon in people.

Who is most at risk of Copper deficiency?

Even though copper deficiency is rare, it might occur in individuals with certain conditions, which can cause anemia, hypopigmentation, elevated cholesterol levels, connective tissue disorders, osteoporosis and other bone defects.

Individuals with Coeliac disease

Research involving individuals diagnosed with coeliac disease found that the impaired absorption caused by the changes in the intestinal lining associated with coeliac disease caused a lower copper level.

The result found that copper levels were lower than 70 mcg/dL in the serum for men and girls under 12 years old, and lower than 80 mcg/dL in women.[2]

RELATED — Coeliac Disease: Symptoms and Effects on our health and body

Individuals with Menkes disease

Copper deficiency is common in those with Menkes disease. This condition causes low copper levels in blood plasma, liver and brain and also reduces the activities of copper-dependent enzymes in the body.

Menkes disease is characterised by an inability to transport copper across the intestinal barrier due to a mutation of ATP7A gene, which plays an important role in copper transportation process.[3]

Menkes disease can be treated with copper supplementation, provided by daily subcutaneous injections. However, the results vary regarding the severity of the ATP7A mutation and the type of copper complex used.

This disease will affect nearly all areas of the body, which is why it is important to diagnose Menkes disease and start the treatment as soon as possible, within 28 days of birth.[4]

Excessive zinc consumption

Excessive use of zinc supplementation can interfere with copper absorption, leading to lower copper levels. Zinc and copper compete for absorption in the stomach, which results in copper not being absorbed.

A study showed that intake of zinc approximately 60mg/day for 10 weeks caused a reduction in erythrocyte copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, which is a marker of copper status.

Copper and zinc compete for absorption

The findings on zinc and copper competition become one reason for the establishment of the upper limit for zinc at 40mg/day for adults.[5]

Different types of Copper

Copper can be available in supplements in combination with other ingredients. These supplements contain a variety of different chemical forms of copper.[6]

Copper gluconate

This is a common form of copper used in dietary supplements. Copper gluconate is a copper salt of gluconic acid, which is an oxidized form of dextrose and is often used to provide a source of dietary copper.

Copper sulphate

Copper sulphate is another form of copper used in supplements and animal feed. It contains copper in the divalent form (Cu2+).

Copper oxide

This is the less commonly used form of copper in supplements. It contains copper in the form of copper(III) oxide.

Copper amino-acid chelate

Copper chelate refers to a compound formed by binding copper ions to a chelating agent. Chelation is a chemical process where a chelating agent, forms a stable complex with a metal ion including copper. It is commonly used for supplementation due to its ability to provide a stable and bioavailable source of copper.

To this day, copper chelate is considered to be the most bioavailable.

Health benefits of Copper

Anemia

Anemia is a condition characterised by a reduced number of red blood cells or a decreased amount of hemoglobin, which can lead to reduced oxygen-carrying capacity in the blood.

Copper is a cofactor for several enzymes involved in the conversion of iron to its functional form, which is necessary for hemoglobin synthesis.

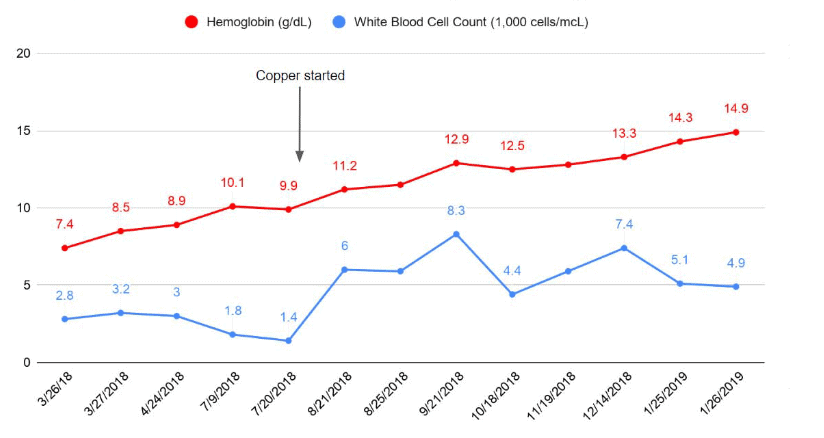

A case report study showed a 32-year-old woman who had anemia and neutropenia for four months. Her lab test reported a low serum copper level of 1 mg/dL (normal 80-155mg/dL) and ceruloplasmin to be <2mg/dL (normal 21-53mg/dL).

After being given oral copper gluconate (copper supplement) of 2mg/day for one month, her hematological abnormalities improved.[8]

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurological disorder characterised by cognitive decline, memory loss, and changes in behaviour and thinking abilities.

The exact cause of Alzheimer’s disease is still uncertain, but it is known to be influenced by a combination of genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors.

The emerging area of study has explored the role of trace minerals imbalance, including copper, in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

A meta-analysis of case-control studies showed higher blood concentrations of copper in people with Alzheimer’s disease compared to healthy individuals from a total of 46 studies reviewed.[9]

Another study examined the association between dietary copper with increased cognitive decline among individuals who also consume a high saturated and trans fat diet.

RELATED — Health Risks: Trans and Saturated Fats

The study showed that higher copper intake was associated with a faster rate of cognitive decline. The median for the highest intake was 2.75mg/day compared to the lowest 0.88mg/day. However, copper intake did not affect cognitive change among individuals whose diets were not high in fats.[10]

Cancer

Copper may play a role in cancer for several reasons. It supports angiogenesis, the growth of blood vessels that feed a tumour and activates enzymes and signalling proteins used by cancer cells.

An emerging area of research has focused on the role of copper in metastatic cancer cells, which are cells that break away from a primary tumour and spread to other areas in the body.

Levels of copper in these aggressive cells were found to be higher than in non-metastatic cancer cells. Intentionally depleting copper levels by blocking its bioavailability may reduce the energy these cells need to travel throughout the body.[11]

A meta-analysis study by Zhang et al. observed the association between serum copper levels in patients with lung cancer. The overall analysis showed that serum copper levels tend to be higher in people with lung cancer compared with individuals without lung cancer.[12]

Cardiovascular disease

Copper deficiency leads to changes in blood lipid levels, a risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Few animal studies have shown that copper deficiency is associated with cardiac abnormalities.

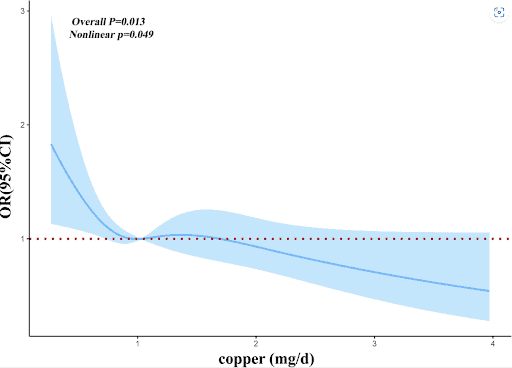

A study by Wen et al. examined the association between serum copper and myocardial infarction. They included various studies with 14,876 participants from 2011 to 2018.

The results showed that increased dietary copper intake was associated with a lower risk of myocardial infarction. The average dietary copper intake was 1.0825mg/day. In addition, this result is more significant in elderly women, overweight individuals, smokers, individuals with hypertension and diabetic patients.[13]

However, copper can have “pro-oxidant” effects that potentially cause stress and damage to cells. The muscles in the heart contain high concentrations of copper and may be negatively affected by either a deficiency or high levels of this mineral. Both conditions have been associated with atherogenesis, the early build-up of plaque in heart arteries.[11]

Copper can have pro-oxidant effect

A cohort study determined serum copper levels in more than 4,500 men and women for 30 years. After adjusting the other risk factors, the study showed that those with higher serum copper levels had a significantly greater risk of dying from coronary heart disease. Serum copper concentration was about 5% higher among individuals who died from coronary heart disease than those who did not.[14]

Bone health

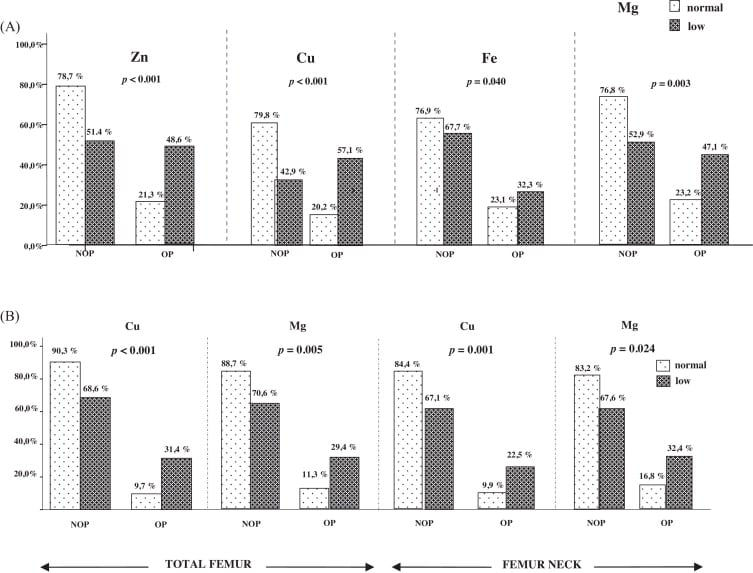

Severe copper deficiency is associated with lower bone mineral density and a higher risk of osteoporosis. Women are more often affected by osteoporosis than men, due to the reduction in the production of estrogen after menopause.

RELATED — Menopause: Detailed Guide to Signs and Symptoms

One study looked at the relationship between serum main minerals, including copper, and postmenopausal osteoporosis. There were 728 postmenopausal women included in this study, divided into groups with the presence or absence of osteoporosis.

The result showed that low serum copper levels were significantly associated with osteoporosis according to bone mineral density values.[15]

Another study determined the association between bone mineral density and total fracture. The results showed that balanced serum copper levels are essential for bone health.

Lower serum copper levels are significantly associated with decreased bone mineral density. In saying that, higher serum copper levels are significantly associated with an increased risk of total fracture.[16]

However, future research is required due to limited intervention studies and mixed results regarding the relationship between copper levels on bone health.

Health claims that still need more evidence and research

There have been various health claims about copper’s potential health benefits that still require further research and validation. Some of these claims are shared below.

Immune system

Recent studies found that copper plays an important role in immune system function. During infection, the level of serum copper metabolism increases and ceruloplasmin activity also increases. Lack of copper will lead to impaired energy production and affect the work of the immune system.[17]

A study by Li et al. determined the role of copper homeostasis in the resistance to pathogens such as E. coli and Salmonella. Analysis of copper homeostasis in bacteria showed that copper is utilised by the host immune system as an antimicrobial agent.[18]

Skin and hair health

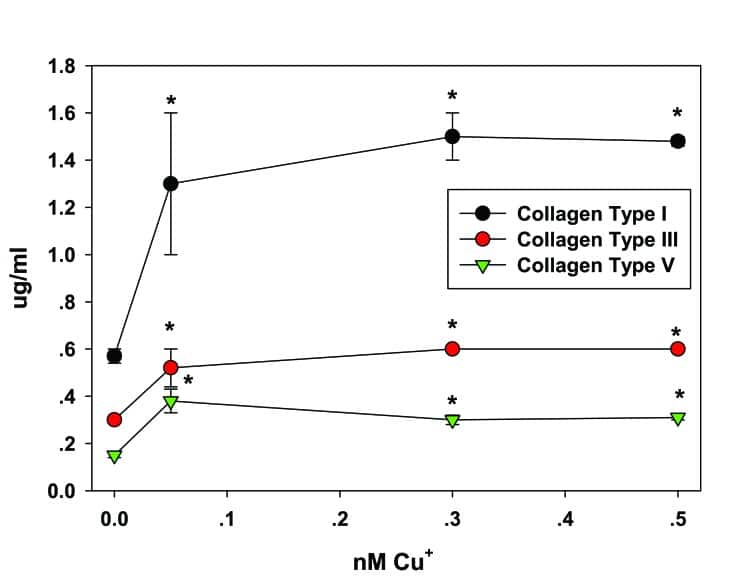

Copper has a key role in the synthesis and stabilisation of skin proteins, which is believed to help improve skin well-being. Copper stimulates the regulation of collagen from fibroblast, which is a protein responsible for skin elasticity or stretchiness.

Furthermore, copper is also a cofactor of tyrosinase, a melanin biosynthesis essential enzyme responsible for skin and hair pigmentation.[19]

However, further research is needed to determine the efficacy and safety of this intervention.

Best sources of Copper

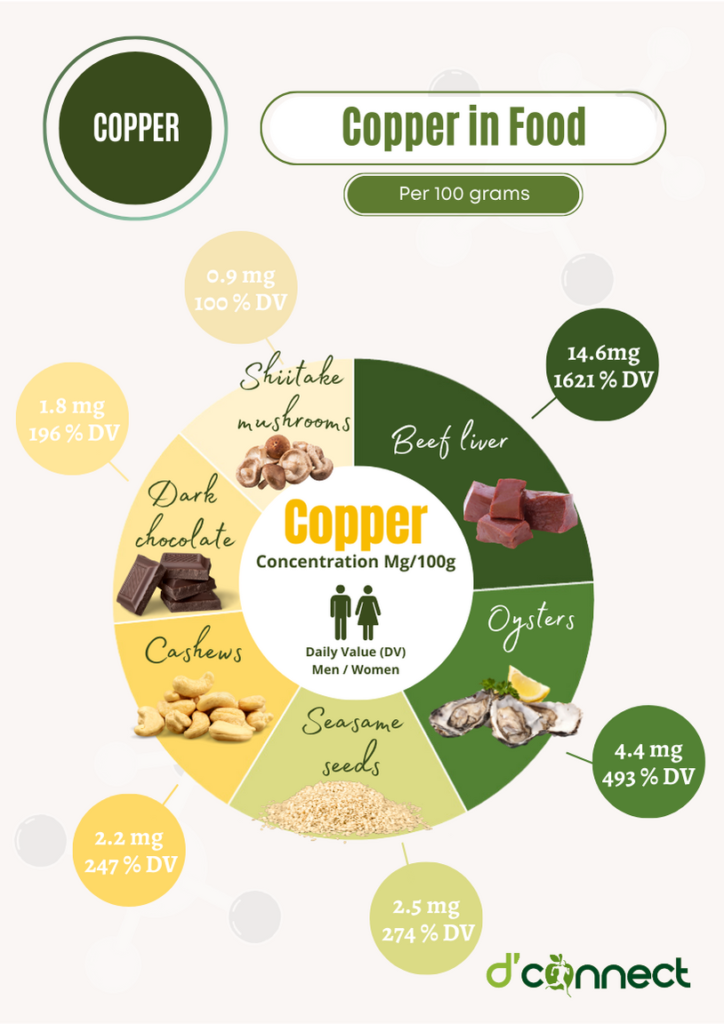

Maintaining an adequate intake of copper through a balanced diet is essential for overall health. Copper can be obtained from various food sources as shown in the table below.[20]

Food Source | Concentration (mg/100g) | Daily Value (DV) Men/Women |

Beef liver | 14.6mg | 1621% |

Oysters | 4.4mg | 493% |

Sesame seeds | 2.5mg | 274% |

Cashews | 2.2mg | 247% |

Dark chocolate (70-85% cocoa) | 1.8mg | 196% |

Shiitake mushrooms | 0.9mg | 100% |

Tempeh | 0.6mg | 62% |

Firm tofu | 0.4mg | 42% |

Chickpeas | 0.4mg | 39% |

Soybean sprouts | 0.3mg | 37% |

Edamame | 0.3mg | 37% |

Salmon | 0.3mg | 36% |

Sweet potatoes | 0.3mg | 31% |

Avocados | 0.2mg | 21% |

Quinoa | 0.2mg | 21% |

As we can see, a wide variety of plant and animal foods contain copper, and studies report that the average human diet provides approximately 1,400mcg/day for men and 1,100mcg/day.

Hence, a healthy and balanced diet should meet or exceed the daily copper requirements.

Note — Feel free to download and share this illustration.

Daily requirements and recommended intake

The methods to assess copper status in humans include the measurement of the activities of certain copper enzymes. Serum copper or serum ceruloplasmin are most often used to assess copper status.

Human studies typically measure copper and cuproenzyme (CP) activity in plasma and blood cells.[21]

Age | Male | Female |

0-6 months | 0.2mg/day | 0.2mg/day |

7-12 months | 0.22mg/day | 0.22mg/day |

1-3 years | 0.7mg/day | 0.7mg/day |

4-8 years | 1mg/day | 1mg/day |

9-13 years | 1.3mg/day | 1.1mg/day |

14-18 years | 1.5mg/day | 1.1mg/day |

19+ years | 1.7mg/day | 1.2mg/day |

For pregnancy and lactation, the amount increases to 1.3mg and 1.5mg, respectively.

How to take Copper as a supplement

Multivitamins that include minerals usually have copper. It is also available as a separate oral supplement and can be found as a topical gel and in topical solutions.

Copper supplements are generally better absorbed when taken with food. This can also minimise potential digestive discomfort.

When taking copper supplements, it is also recommended to take a zinc supplement with the proper ratio, as an imbalance of these two minerals can cause other health problems.[22]

Copper supplements should only be taken under the guidance of a healthcare professional, as excessive intake of copper can lead to toxicity.

Common signs and symptoms of Copper deficiency

Copper deficiency is relatively rare, but when it does occur there might be both mild and severe symptoms. Common signs and symptoms of copper deficiency include:

- Anemia

- Low body temperature

- Low white blood cell count

- Irregular heartbeat

- Loss of pigment from the skin

- Thyroid problems

- Bone fractures and osteoporosis

It would be advisable to check your copper levels once a year.

Copper risks and side effects

Copper toxicity is rare in healthy individuals who do not have a hereditary copper homeostasis defect. The maximum daily intake of copper from food and supplements is 10mg/day for adults.

Chronic exposure to high levels of copper can result in liver damage and gastrointestinal symptoms such as:

- abdominal pain

- cramps

- nausea

- diarrhea

- vomiting

People with Wilson’s disease, which is a rare autosomal recessive disease, have a high risk of copper toxicity. This disease leads to abnormally high tissue levels of copper as a result of defective copper clearance

Possible interaction with herbs and supplements

Excess intake of zinc supplements at doses up to 50mg/day or more for extended periods of time may result in copper deficiency.

Further studies indicate that copper supplementation along with zinc helps balance the absorption of both nutrients.

Practitioners recommend a ratio of 15mg of zinc to 1mg of copper, which is similar to the recommended intake.

Possible interaction with medications

It’s important to be aware and consult with a healthcare provider before taking any copper supplementation and medications shared below.[23]

Birth control pills and estrogen (following menopause)

These medications can increase blood levels of copper. Therefore, copper supplementation is not appropriate and may be a cause for concern.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Copper binds to NSAIDs (including ibuprofen and naproxen) and appears to enhance their anti-inflammatory activity.

Penicillamine

Penicillamine is a medication used to treat Wilson’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. It reduces copper levels, which may be the intended use, as in the case of Wilson’s disease.

Allopurinol (Zyloprim)

An in vitro study reported that allopurinol, a medication to treat gout, might reduce copper levels.

Cimetidine (Tagamet)

Animal studies show that Tagamet, a medication used to treat ulcers and gastroesophageal reflux disease, may elevate copper levels in the body, leading to liver damage.

Summary

It’s best to obtain copper through a balanced diet.

Key Takeaway — In this illustration we have outlined the most important information that you should know about Copper.

Related Questions

1. How much copper is there in eggs?

100 grams of eggs contain 0.1mg of copper, which is 8% of the dietary value.

2. Should I supplement with zinc if I am taking a copper supplement?

Yes, it is recommended to take zinc supplement with copper supplement.

The ratio should be for every 15mg of zinc, you should take 1mg of copper.

3. Which fruit has the highest copper content?

Guava and avocado have the highest copper content with 0.2mg per 100g, which is 23% of the daily value.

We will soon be sharing our first e-book that will have the most important information on Top 5 vitamins and minerals that you should have in your diet. If you would like to receive the e-book, please subscribe and we’ll forward you a free copy.

Bernadeth’s passion in cooking, food and health led her to learn more about nutrition and the importance of functional foods. Throughout the years, she gained special interest in sports and performance nutrition, and the varieties of diets around the world. As a nutritionist, Bernadeth’s goal is to encourage a healthy-balanced diet and share the evidence-based nutrition knowledge in order for people to live healthier and longer lives.

Bernadeth is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect

References

(1) Davis, W. (1928). Discovery of Copper As Aid To Nutrition. Current History (1916-1940), 28(6), 1003–1006. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45338000

(2) Botero-López, J. E., Araya, M., Parada, A., Méndez, M. A., Pizarro, F., Espinosa, N., Canales, P., & Alarcón, T. (2011). Micronutrient deficiencies in patients with typical and atypical celiac disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, 53(3), 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181f988fc

(3) Costa, L. S., Pegler, S. P., Lellis, R. F., Krebs, V. L., Robertson, S., Morgan, T., Honjo, R. S., Bertola, D. R., & Kim, C. A. (2015). Menkes disease: importance of diagnosis with molecular analysis in the neonatal period. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira (1992), 61(5), 407–410. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.61.05.407

(4) Menkes Disease. (2023). Retrieved from https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/conditions/menkes-disease#:~:text=Menkes%20disease%20 usually%20 causes%20 low,tissues%2C%20such%20as%20the%20kidney

(5) Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Micronutrients. (2001). Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222310/

(6) Burkhead, J. L., & Collins, J. F. (2022). Nutrition Information Brief-Copper. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 13(2), 681–683. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmab157

(7) Rosado J. L. (2003). Zinc and copper: proposed fortification levels and recommended zinc compounds. The Journal of nutrition, 133(9), 2985S–9S. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022316622161560?via%3Dihub

(8) Harless, W., Crowell, E., & Abraham, J. (2006). Anemia and neutropenia associated with copper deficiency of unclear etiology. American journal of hematology, 81(7), 546–549. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ajh.20647

(9) Squitti, R., Ventriglia, M., Simonelli, I., Bonvicini, C., Costa, A., Perini, G., Binetti, G., et al. (2021). Copper Imbalance in Alzheimer’s Disease: Meta-Analysis of Serum, Plasma, and Brain Specimens, and Replication Study Evaluating ATP7B Gene Variants. Biomolecules, 11(7), 960. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/biom11070960

(10) Morris, M. C., Evans, D. A., Tangney, C. C., Bienias, J. L., Schneider, J. A., Wilson, R. S., & Scherr, P. A. (2006). Dietary copper and high saturated and trans fat intakes associated with cognitive decline. Archives of neurology, 63(8), 1085–1088. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.63.8.1085

(11) Chan, H. T. H. (2023). Copper. The Nutrition Source. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/copper/

(12) Zhang, X., & Yang, Q. (2018). Association between serum copper levels and lung cancer risk: A meta-analysis. The Journal of international medical research, 46(12), 4863–4873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060518798507

(13) Wen, H., Niu, X., Hu, L., Sun, N., Zhao, R., Wang, Q., & Li, Y. (2022). Dietary copper intake and risk of myocardial infarction in US adults: A propensity score-matched analysis. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 9. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.942000

(14) Ford E. S. (2000). Serum copper concentration and coronary heart disease among US adults. American journal of epidemiology, 151(12), 1182–1188.

(15) Okyay, E., Ertugrul, C., Acar, B., Sisman, A. R., Onvural, B., & Ozaksoy, D. (2013). Comparative evaluation of serum levels of main minerals and postmenopausal osteoporosis. Maturitas, 76(4), 320–325.

(16) Qu, X., He, Z., Qiao, H., Zhai, Z., Mao, Z., Yu, Z., & Dai, K. (2018). Serum copper levels are associated with bone mineral density and total fracture. Journal of orthopaedic translation, 14, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2018.05.001

(17) Liu, Y., Zhu, J., Xu, L., Wang, B., Lin, W., & Luo, Y. (2022). Copper regulation of immune response and potential implications for treating orthopedic disorders. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 9. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2022.1065265

(18) Li, C., Li, Y., & Ding, C. (2019). The Role of Copper Homeostasis at the Host-Pathogen Axis: From Bacteria to Fungi. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20010175

(19) Borkow G. (2014). Using Copper to Improve the Well-Being of the Skin. Current chemical biology, 8(2), 89–102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4556990/

(20) Whitbread, D. (2023). Top 10 Foods Highest in Copper. My Food Data. Retrieved from https://www.myfooddata.com/articles/high-copper-foods.php#copper-rich-foods

(21) Commonwealth of Australia. (2006). Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Retrieved from https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/nutrient-reference-values/nutrients/copper

(22) Mount Sinai. (2023). Copper. Retrieved from https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/supplement/copper#:~:text=Signs%20of%20possible%20copper%20deficiency,the%20skin%2C%20and%20thyroid%20problems

(23) St. Luke’s Hospital. (2007). Possible Interactions with: Copper. Retrieved from https://www.stlukes-stl.com/health-content/medicine/33/000951.htm