Aysegul Aktalay

(Registered Counsellor NZAC, MCouns, Psychology BSc, EMDR Therapist)

While we may wake up one day feeling depressed, we need to understand that depression is a gradual process of decline.

This might sound terrifying, however, if we know what to look out for when it comes to changes in our behavior, this gives us a fighting chance to overcome depression, before we hit bottom.

Apart from the signs and symptoms we discussed in Part 1 of the article, we also need to be aware that depression can cause issues with our:

- gastrointestinal health

- energy levels

- will and interest

- libido

- sleep quality and duration

These are the areas that we discuss in more detail in the article.

Gastrointestinal issues

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent, and potentially debilitating functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by recurring abdominal pain and changes in bowel habits.

RELATED — Introduction to Probiotics: Our immunity boosters

In Fond’s (2014) study, the first meta-analysis aimed to estimate anxiety and depression levels in adults with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and compared 11 studies with an overall sample size of 885 patients and 1,384 healthy controls.

The study confirmed higher levels of anxiety and depression in patients with IBS compared to healthy controls.[1]

Individuals with IBS have higher levels of anxiety and depression

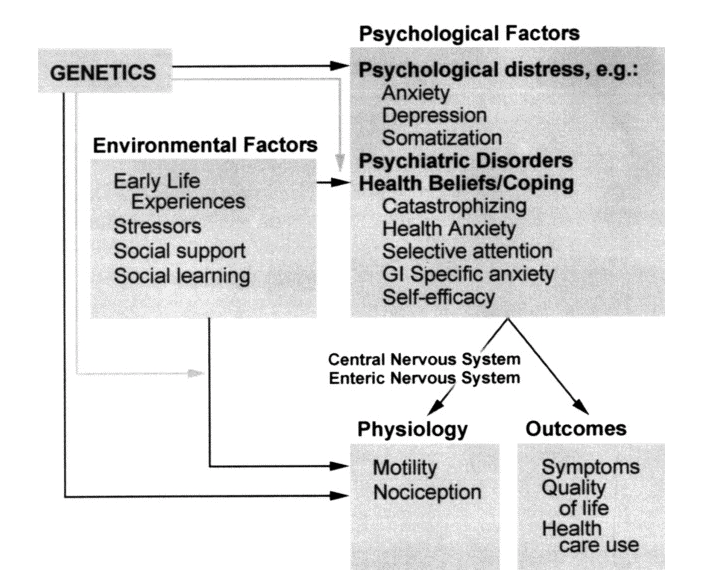

Levy (2006) explores the psychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), highlighting the significant challenges faced by patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

These challenges include psychological distress, childhood trauma, and recent environmental stress, which are also associated with several other FGIDs.[2]

Energy levels

Lam et al. (2018) explore how abnormalities in the white matter, which is the brain tissue responsible for transmitting movement signals, are linked to late-life depression (LLD) in older adults.

White matter abnormality can disrupt communication between the brain and the body, potentially leading to movement or mood problems, such as those seen in LLD.

The study, involving 28 older adults with depression and 23 healthy controls, found that the volume of the right corticospinal tract was significantly higher in depressed individuals and was linked to the severity of depression and perceived energy levels.

RELATED — Introduction to: Depression

This suggests that a higher volume in the right corticospinal tract may contribute to LLD and lower perceived energy levels in older adults with depression.[3]

Loss of will and interest

Loss of interest, a symptom of depression, is closely tied to anhedonia, the inability to find pleasure in previously enjoyable activities. Anhedonia can manifest as a lack of interest in socializing, hobbies, or self-care, contributing to feelings of emptiness and sadness.

RELATED — Introduction to Logotherapy: Our meaning and purpose in life

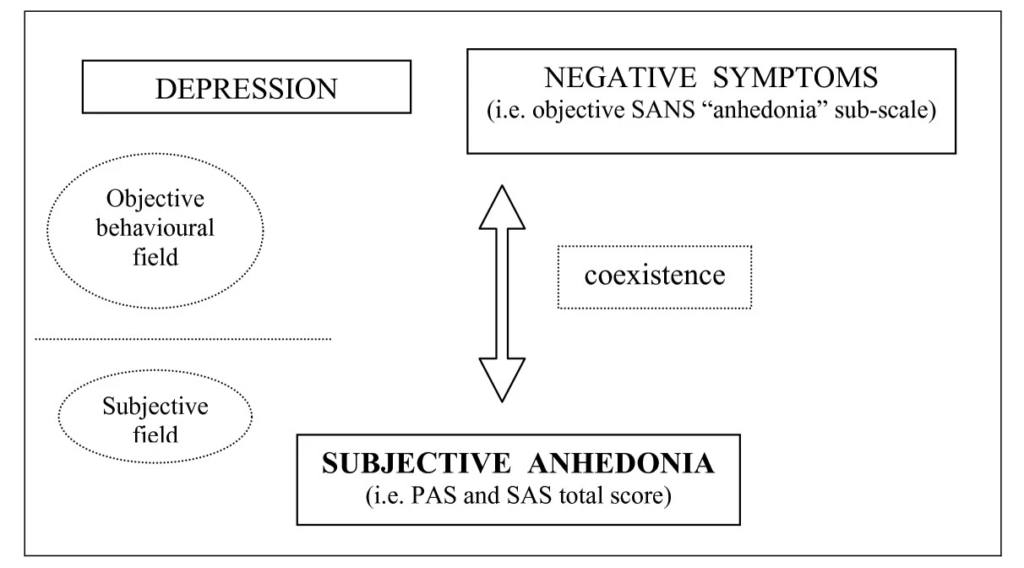

Pelizza and Ferrari (2009) conducted a study on anhedonia in schizophrenia and major depressive disorder to investigate whether it is a trait or a state and its relationship with other symptoms.

They assessed 145 patients (80 with schizophrenia, 65 with depression) and found that anhedonia was significantly present in 45% of schizophrenic patients and 36.9% of depressed patients.

In individuals with schizophrenia, anhedonia was associated with disorganization and negative symptoms.

Individuals with depression, anhedonia was correlated with the severity of depression and negative symptoms.[4]

Libido

Sexual dysfunction can manifest as a symptom of depression or as a side effect of many antidepressants.

A 2009 study explored sexual dysfunction in depression and its connection to antidepressant treatment. They observed that sexual dysfunction, such as

- reduced libido

- difficulties with arousal

- difficulties with achieving orgasm

is prevalent in depression and can be exacerbated by antidepressants.

Sexual dysfunction can happen during depression

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a common class of antidepressants, have particularly pronounced effects on arousal and orgasm compared to other antidepressants.

Recognizing and addressing sexual dysfunction is crucial for improving treatment adherence and minimizing the need to change medications.[5]

Sleep issues

A 2014 study examined the link between self-reported sleep difficulties and the onset of depression and anxiety in young Australian women.

They analyzed 9,683 women surveyed in 2000, 2003, 2006, and 2009, and found a significant association between frequent sleeping difficulties reported in 2000 and the development of new-onset depression and anxiety at each subsequent survey.

Specifically, women who often experienced sleeping difficulties in 2000 had a higher risk of developing depression and anxiety in 2003, 2006, and 2009.[6]

RELATED — Great Sleep means Great Health

Substance use

In 2017, a systematic review of 148 longitudinal studies examined the association between smoking and mental health, and the results showed a complex relationship with

- some studies suggesting a link between baseline depression/anxiety and later smoking

- other studies indicating an association between smoking and subsequent depression/anxiety

A study on substance use, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among college students, that involved 1,316 undergraduates, found that depressive symptoms were associated with the use of various substances, including

- cannabis

- tobacco

- amphetamines

- cocaine

- sedatives

- hallucinogens

However, anxiety symptoms did not show a significant association with substance use.

These results emphasize the importance of education and prevention efforts in universities, particularly focusing on substances like tobacco, cannabis, and certain “harder” drugs.[7]

Suicidal thoughts

Nock and colleagues (2010) explored the connection between mental disorders and suicidal behaviors using data from a survey of 9,282 US adults.

They discovered that mental disorders strongly predict suicide attempts, with around 80% of attempters having a prior mental disorder. Initially, anxiety, mood, impulsive-control, and substance use disorders were all significant predictors of suicide attempts.

However, these associations weaken when considering comorbidity.

Depression was linked to suicidal thoughts, but not plans or attempts among those with such thoughts.

Instead, disorders characterized by severe anxiety/agitation and poor impulse control predicted suicide plans or attempts among those who had suicidal thoughts.[8]

Related Questions

1. Does depression cause damage to the brain?

Depression does not cause major irreversible damage to the brain but induces adaptive and reversible changes in hippocampal structure rather than significant cell loss or neuropathology.[9]

2. Can light therapy help with depression?

A systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that light therapy is moderately effective in alleviating symptoms of non-seasonal depression compared to placebos and controls.[10]

3. Can depression cause brain fog?

Research shows that depression can affect neural networks in critical areas of the brain, which may contribute to brain fog.

For instance, depression can impact the hippocampus, which supports memory recall, the amygdala, which aids in decision-making, and the basal ganglia, which enhances working memory performance.

Changes in these brain regions due to depression may lead to the experience of brain fog.[11]

If you have just joined us, you can read the first article here — Depression Signs and Symptoms: Stop the downward spiral in time (Part 1).

Aysegul is a full member and a registered counsellor for New Zealand Association of Counsellors and is also a member of EMDRNZ (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing New Zealand). She has more than ten years of experience as a counselling psychologist overseas, which today serves as a foundation for her in-depth clinical skills…

If you would like to learn more about Aysegul, see Expert: Aysegul Aktalay.

References

(1) Fond, G., Loundou, A., Hamdani, N., Boukouaci, W., Dargel, A., Oliveira, J., Roger, M., Tamouza, R., Leboyer, M., & Boyer, L. (2014). Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 264(7), 651–660.

(2) Levy, R. L., Olden, K. W., Naliboff, B. D., Bradley, L. A., Francisconi, C., Drossman, D. A., & Creed, F. (2006). Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology, 130(5), 1447–1458. Retrieved from https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(06)00505-1/fulltext

(3) Lam, C. L. M., Liu, H.-L., Huang, C.-M., Wai, Y.-Y., Lee, S.-H., Yiend, J., Lin, C., & Lee, T. M. C. (2019). The neural correlates of perceived energy levels in older adults with late-life depression. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 13(5), 1397–1405. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11682-018-9940-y

(4) Pelizza, L., & Ferrari, A. (2009). Anhedonia in schizophrenia and major depression: State or trait? Annals of General Psychiatry, 8, 22. Retrieved from https://annals-general-psychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1744-859X-8-22

(5) Kennedy, S. H., & Rizvi, S. (2009). Sexual Dysfunction, Depression, and the Impact of Antidepressants. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(2).

(6) Jackson, M. L., Sztendur, E. M., Diamond, N. T., Byles, J. E. & Bruck, D. (2014). Sleep difficulties and the development of depression and anxiety: a longitudinal study of young Australian women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, pp.189-198.

(7) Fluharty, M., Taylor, A. E., Grabski, M., & Munafò, M. R. (2017). The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(1), 3-13. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/ntr/article/19/1/3/2631686

(8) Nock, M. K., Hwang, I., Sampson, N. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Mental disorders, comorbidity, and suicidal behavior: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of Affective Disorders, 15(7), 868-876.

(9) Swaab, D. F., Bao, A.-M., & Lucassen, P. J. (2005). The stress system in the human brain in depression and neurodegeneration. Ageing Research Reviews, 4(2), 141-194. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1568163705000048

(10) Perera, S., Eisen, R., Bhatt, M., Bhatnagar, N., de Souza, R., Thabane, L., & Samaan, Z. (2016). Light therapy for non-seasonal depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open, 2(2), 116-126. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4998929/

(11) Wang, Y.-B., Song, N.-N., Ding, Y.-Q., & Zhang, L. (2023). Neural plasticity and depression treatment. IBRO Neuroscience Reports, 14, 160-184. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S266724212200063X