Paloma Velasquez

(NMHNZ, MD)

Note — The article was checked and updated June 2023.

Dandelion is a plant known to many by its yellow flowers. Fields and meadows are often full with yellow dots from afar. Apart from being a visually extraordinary plant, Dandelion is also known to have many medicinal uses, as well as containing vitamins A, B, C, D, minerals, potassium, calcium, iron, phosphorus, copper, inulin, sodium, and zinc.

We discuss in more detail below the health and nutritional benefits, medicinal and culinary uses as well as potential risks and what to be aware of if you are using different medications.

Introduction

Dandelions grow abundantly worldwide, with the exception of places with extreme temperatures.[1] Dandelions belong to the Asteraceae family and to the Cichorioideae subfamily. They can grow throughout the year and are a perennial plant.[2]

Although sometimes it is treated as a weed, it is a nutritious plant and has been used to support a variety of health concerns for hundreds of years.[1]

Other names

Botanical name: Taraxacum officinale

Common names:

- English: dandelion, wet-a-bed, lion’s tooth

- French: dent-de-lion, pissenlit

- German: Löwenzahn, Pfaffenrohrlein

- Spanish: diente de león

- Italian: tarassaco

- Chinese: pu gong ying, Ching p’o po, chiang-nou-ts’ao, huang-hua-tii-ting[3]

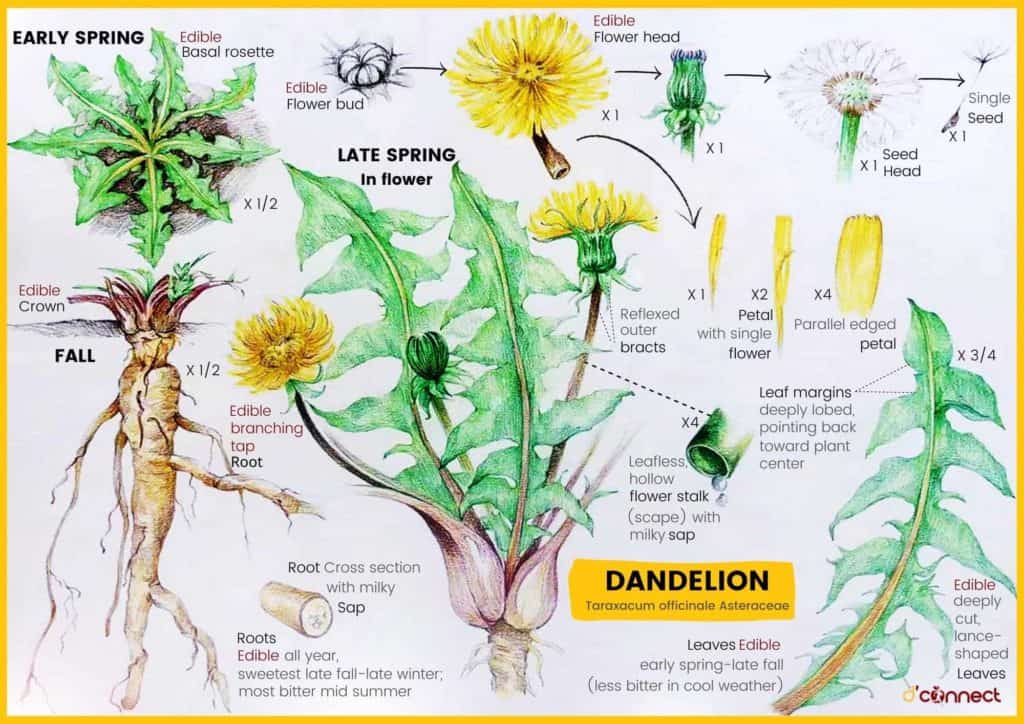

Characteristics

Dandelion leaves arise from the root. They are toothed, shiny, smooth, hairless, with a hollow midrib, and grow in the form of a rosette. The plant can reach up to 40cm in height. The flowers are yellow and have many strap-shaped petals. There is one flower per stalk, which is hollow, and may exudate latex.[2]

Dandelions have an earthy smell. They grow in gardens, lawns, parks, and cracks in pavements, and waste lots all over the temperate world.[1,3] Many species of plants have dandelion-like leaves.[2]

Dandelion has tap roots, which contain a milky sap.[4]

Use

Dandelion has been used medicinally and culinarily since ancient times. There is history from China, North America, Germany, and Turkey using dandelion as a treatment for various ailments.[5]

The whole dandelion is edible. The flowers were used in Europe to prepare drinks and salads.[6]

Medicinal use

Traditionally, dandelion leaves have been used as a diuretic and the root as a liver tonic. Today, there is some research conducted in animals and in vitro that relates to some of the actions of dandelion.

A small clinical trial by Clare et al. (2009) reported an increase in urination when taking dandelion leaf extract.[7] Leaves have been described to have a stronger diuretic effect compared to the root.[8]

Dandelions have been used as a diuretic in the past

The bitter constituents present in dandelion root are believed to support healthy functioning of gallbladder and regular bowel movements.[6]

A research study conducted by Maliakal and Wandwimolruk (2001) reported a decreased activity of CYP1A2 and CYP2E, and an incrementation in the levels of the phase-II detoxifying enzyme UDP – glucuronosyltransferase in the liver microsomes of rats taking Dandelion tea.[9]

Dandelion root has also been used to support digestion. Dandelion root contains oligo-fructans, and Trojanova et al. (2004) reported a growth of some strains of bifidobacteria from a dandelion root infusion.[10] Also, the leaf and root have been described to have an antirheumatic effect.[6,11]

Dandelion has been described to support the inflammatory process. In vivo and in vitro studies have shown anti-inflammatory activity from a dandelion extract.[6]

Tito et al. (1993) exhibited that after taking a dandelion extract, there was a mild analgesic and anti-inflammatory effect. In vitro studies have shown that that dandelion influences inflammatory mediators such as COX-2, TNF-alpha, IL-1, iNOS, in astrocytes, leukocytes and macrophages.[12]

Dandelion may also support the oxidation-reduction (redox) reaction. The entire dandelion plant has shown antioxidant activity in a variety of mice and in vitro studies.[13,14,15,16]

Adding to this, traditional Chinese medicine, native Americans and Arabia traditional medicine have used dandelion for a variety of ailments, including cancer. At the moment, there are only a few studies, in vitro and in animals, that have studied the effect of dandelion in cancer, and more studies are needed to provide conclusive evidence.[6,17,18]

Culinary use

Dandelion leaves have a bitter taste, while younger leaves are less bitter. Leaves can be used as a substitute for any other dark leafy greens; they can be used in salads, pesto, stir-fry, quiche, soups, and more.[6]

RELATED — What is plant-based diet: Vegan or Vegetarian

Seeds can be sprouted, ground or eaten, and roots are edible all year.

The sweetness, though, is late fall and winter, while roasted root can be used as a coffee substitute.[4,6]

The entire dandelion plant is edible

Flowers have been used to prepare drinks, salads, sweet and savory baking, and in the past, an extract from the flowers was added to candy, gelatin, puddings, and cheese.[19,20]

Nutritional facts

According to the U.S department of agriculture, 1 cup (55 g) of Dandelion leaves contain[21]

Name | Amount | Unit |

Water | 47.1 | g |

Energy | 24.8 | kcal |

Energy | 103 | kJ |

Protein | 1.48 | g |

Total lipid (fat) | 0.385 | g |

Ash | 0.99 | g |

Carbohydrate, by difference | 5.06 | g |

Fiber, total dietary | 1.92 | g |

Sugars, total including NLEA | 0.391 | g |

Calcium, Ca | 103 | mg |

Iron, Fe | 1.7 | mg |

Magnesium, Mg RELATED — Magnesium (for a great night of sleep) | 19.8 | mg |

Phosphorus, P | 36.3 | mg |

Potassium, K RELATED — Potassium (for blood pressure, heart rhythm and pH balance) | 218 | mg |

Sodium, Na | 41.8 | mg |

Zinc, Zn | 0.226 | mg |

Copper, Cu RELATED — Copper: Heart, Hair and Skin Health | 0.094 | mg |

Manganese, Mn | 0.188 | mg |

Selenium, Se | 0.275 | µg |

Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid RELATED — Vitamin C: Immunity and Collagen booster | 19.2 | mg |

Thiamine RELATED — Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) | 0.105 | mg |

Riboflavin RELATED — Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) | 0.143 | mg |

Niacin RELATED — Vitamin B3 (Niacin) | 0.443 | mg |

Pantothenic acid RELATED — Vitamin B5 (Pantothenic Acid) | 0.046 | mg |

Pyridoxine RELATED — Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) | 0.138 | mg |

Folate, total | 14.8 | µg |

Folic acid | 0 | µg |

Folate, food | 14.8 | µg |

Folate, DFE | 14.8 | µg |

Choline, total | 19.4 | mg |

Vitamin B-12 | 0 | µg |

Vitamin B-12, added | 0 | µg |

Vitamin A, RAE | 279 | µg |

Retinol | 0 | µg |

Carotene, beta | 3220 | µg |

Carotene, alpha | 200 | µg |

Cryptoxanthin, beta | 66.6 | µg |

Vitamin A, IU | 5610 | IU |

Lycopene | 0 | µg |

Lutein + zeaxanthin | 7480 | µg |

Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) | 1.89 | mg |

Vitamin E, added | 0 | mg |

Vitamin D (D2 + D3), International Units | 0 | IU |

Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | 0 | µg |

Vitamin K (phylloquinone) | 428 | µg |

Fatty acids, total saturated | 0.094 | g |

SFA 4:0 | 0 | g |

SFA 6:0 | 0 | g |

SFA 8:0 | 0 | g |

SFA 10:0 | 0 | g |

SFA 12:0 | 0 | g |

SFA 14:0 | 0.005 | g |

SFA 16:0 | 0.08 | g |

SFA 18:0 | 0.004 | g |

Fatty acids, total monounsaturated | 0.008 | g |

MUFA 16:1 | 0 | g |

MUFA 18:1 | 0.008 | g |

MUFA 20:1 | 0 | g |

MUFA 22:1 | 0 | g |

Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated | 0.168 | g |

PUFA 18:2 | 0.144 | g |

PUFA 18:3 | 0.024 | g |

PUFA 18:4 | 0 | g |

PUFA 20:4 | 0 | g |

PUFA 2:5 n-3 (EPA) | 0 | g |

PUFA 22:5 n-3 (DPA) | 0 | g |

PUFA 22:6 n-3 (DHA) | 0 | g |

Fatty acids, total trans | 0 | g |

Cholesterol | 0 | mg |

Alcohol, ethyl | 0 | g |

Caffeine | 0 | mg |

Theobromine | 0 | mg |

Root contains vitamins A, B, C, D, minerals, potassium, calcium, iron, phosphorus, copper, inulin, sodium, and zinc. Flowers contain lecithin.[1,22]

Health benefits

Eating dandelion can help to achieve optimal nutrition if consumed as part of a healthy diet.

Health benefits of dandelion

Supporting the nervous system

Choline found in dandelion leaves is needed for cell membranes, and the nervous system needs choline to modulate memory, mood, muscle control and more.[23]

The potassium content from leaf and root, may assist with the requirements needed for proper functioning of the cell, heart and kidney function, nerve conduction and muscle contraction.[24] Flowers contain lecithin, which is necessary for brain function and fat digestion.

RELATED — Diet and the Brain: Fats

Supporting the digestive system and gut health

The inulin present in the root may act as a prebiotic fibre and feed the gut microbiome. A healthy gut ecosystem may support a healthy digestion, absorption of nutrients, and immune response.[1]

Dandelion may assist with liver and gallbladder function, regular intestinal transit, and regulate appetite.[22] The bitter flavor of dandelion has been associated with the chemical constituent sesquiterpene lactones, which has been linked to the actions in the liver.[25]

Supporting the renal functions and kidneys

Dandelion may support kidney function.[22] As a consequence, it may help with diuresis and aid in conditions where there is retention of fluid in the body, and there is a necessity of elimination of toxins through urine.

Therapeutic dosage

Therapeutic dosage for dandelion in an adult is considered to be:

- Infusion of dried leaves: 4–10g, three times a day,

- Leaf tincture: 2-5ml, three times a day,

- Leaf juice: 5ml, twice daily,

- Dried powder: 250-1,000mg, four times a day,

- Decoction of dried root: 2–8g, three times a day.[6]

Dandelion as a fluid extract, tincture, or capsule is also available.

Safety concerns

Dandelion is generally considered a safe herb.[26] People with known allergies to plants from the Asteraceae should be cautious, as it may cause an allergic reaction.[6]

People with known obstruction of the bile ducts or any other serious disorder of the gallbladder and liver should avoid using dandelion.[26]

People with kidney stones should consult their health practitioner prior to use.[22]

Historical use of dandelion as traditional medicine suggests that it should be safe to use in pregnancy and lactation.[6] Nevertheless, always consult with a qualified practitioner to check if it is safe for you to take.

Children who have ingested the white latex from dandelion in quantity have reported nausea, vomit, diarrhea, and palpitations.[22]

(If wildcrafting, make sure that the dandelion has not been sprayed with pesticides).

Dandelion is commonly treated as a weed and sprayed with toxic pesticides to get rid of them. Before collecting dandelions, make sure they have not been sprayed. Pesticides may have a harmful effect on health.[27]

Possible interactions with medications

Controlled studies are unavailable, thus interactions are based on evidence of activity.

Dandelion has possible interactions with quinolone antibiotics, resulting in reduced absorption and efficacy of the antibiotic.

Dandelion may theoretically potentiate the diuretic effect of pharmaceutical diuretics.[6]

Possible interactions with herbs and supplements

Currently there is no evidence of interactions with other herbs or supplements.

Tips

Before “wild harvesting”, make sure that you are 100% confident that the plant is dandelion. Do not harvest plants that have been sprayed with pesticides or that are near polluted areas, such as a motorway.

Wash the leaves and roots well as this will help to eliminate some of the milky sap that is bitter.

Younger leaves are less bitter

Dandelion leaves are great to use in salads, pesto, stir-fry, soups, and baking. If you find them too bitter, start using only a few leaves and mix them with other green veggies such as spinach, kale, or lettuce.

Summary

Note — feel free to download and share this illustration.

We hope you liked the article. If you would like to know when the next Herb of the month will be coming out, you can Subscribe to our Newsletter.

In the meantime, please share the article with your family and friends and encourage them to start foraging, because dandelions grow abundantly in New Zealand.

Paloma Velasquez is a registered Naturopath and Medical Herbalist based in Auckland, New Zealand. She earned her degree from Wellpark College. Also, Paloma is a Medical Doctor, completing her studies from Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

She is the founder of Aruraqi, and offers health consultations with an integrative approach. Paloma is passionate about educating and empowering people in the community through workshops and healthy cooking classes.

References

(1) Burgess, I. (1998). Weeds heal: A working herbal. Viriditas Publishing.

(2) Elpel, T.J. (2018). Botany in a day: The patterns method of plant identification: An herbal field guide to plant families of North America. HOPS Press.

(3) Pizzorno, J., & Murray, M. (2013). Textbook of natural medicine (4th ed.). Elsevier.

(4) Falconi, D. (2013). Foraging & feasting: A field guide and wild food cookbook. Botanical Arts Press, LLC.

(5) Quave, C. L. (2013). Medicinal plant monographs. Retrieved from https://etnobotanica.us

(6) Braun, L., & Cohen, M. (2015). Herbs and natural supplements: An evidence-based guide. (4th ed). Elsevier Health Sciences.

(7) Clare, B.A., Conroy, R.S., & Spelman, K. (2009). The diuretic effect in human subjects of an extract of Taraxacum officinale folium over a single day. J AlternComplement Med,15(8):929-34. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0152. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3155102/

(8) Newell, C.A., Anderson, L.A., & Phillipson, J.D. (1996). Herbal medicines: a guide for health care professionals.The Pharmaceutical Press.

(9) Maliakal, P. P., & Wanwimolruk, S. (2001). Effect of herbal teas on hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes in rats. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology, 53(10), 1323–1329. doi:10.1211/0022357011777819

(10) Trojanová, I., Rada, V., Kokoska, L., & Vlková, E. (2004). The bifidogenic effect of Taraxacum officinale root.Fitoterapia,75(7-8), 760–763. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.09.010

(11) Bone, K. (2007). The ultimate herbal compendium (1st ed.). Phytotherapy Press.

(12) Tita, B., Bello, U., Faccendini, P., Bartolini, R., & Bolle, P. (1993). Taraxacum officinale W. Pharmacological effect of ethanol extract. Pharmacological Research,27, 23-24.

(13) Cho, S. Y., Park, J. Y., Park, E. M., Choi, M. S., Lee, M. K., Jeon, S. M., Jang, M. K., Kim, M. J., & Park, Y. B. (2002). Alternation of hepatic antioxidant enzyme activities and lipid profile in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats by supplementation of dandelion water extract. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry,317 (1-2), 109–117. doi:10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00762-8

(14) Colle, D., Arantes, L. P., Gubert, P., da Luz, S. C., Athayde, M. L., Teixeira Rocha, J. B., & Soares, F. A. (2012). Antioxidant properties of Taraxacum officinale leaf extract are involved in the protective effect against hepatoxicity induced by acetaminophen in mice. Journal of medicinal food, 15(6), 549–556. doi:10.1089/jmf.2011.0282

(15) Kaurinovic, B., Popovic, M., Cebovic, T., & Mimika-Dukic, N. (2003). Effects of Calendula officinalis L. and Taraxacum officinale Weber (Asteraceae) extracts on production of OH radicals. Fresenius Environ Bull, 12:250–253.

(16) Liu, L., Xiong, H., Ping, J., Ju, Y., & Zhang, X. (2010). Taraxacum officinale protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Journal of ethnopharmacology,130(2), 392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.029

(17) Ovadje, P., Chatterjee, S., Griffin, C., Tran, C., Hamm, C., & Pandey, S. (2011). Selective induction of apoptosis through activation of caspase-8 in human leukemia cells (Jurkat) by dandelion root extract. Journal of ethnopharmacology,133(1), 86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.09.005

(18) Stagos, D., Amoutzias, G. D., Matakos, A., Spyrou, A., Tsatsakis, A. M., & Kouretas, D. (2012). Chemoprevention of liver cancer by plant polyphenols. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association, 50(6), 2155–2170. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.04.002

https://www.aristsatsakis.com/images/stories/PdFs/Chemoprevention_of_liver_cancer_by_plant_polyphenols..pdf

(19) González-Castejón, M., Visioli, F., & Rodriguez-Casado, A. (2012). Diverse biological activities of Dandelion. Nutr Rev, 70(9):534-47. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00509.x.

https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/70/9/534/1835513

(20) Rop, O., Mlcek, J., Jurikova, T., Neugebauerova, J., & Vabkova, J. (2012). Edible flowers: A new promising source of mineral elements in human nutrition. Molecules,31;17(6):6672-83. doi: 10.3390/molecules17066672.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6268292/

(21) U.S. Department of Agriculture (2019). Food data central: dandelion greens raw.

(22) Fisher, C. (2009). Materia medica of western herbs. Vitex Medica.

(23) National Institute of Health. (2021). Choline – Consumer fact sheet. Retrieved from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Choline-Consumer/

(24) National Institute of Health. (2021). Potassium – Consumer fact sheet. Retrieved from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Potassium-Consumer/

(25) Mahesh, A., Jeyachandran, R., Cindrella, L., Thangadurai, D., Veerapur, V., & Muralidhara Rao, D. (2010). Hepatocurative potential of sesquiterpene lactones of Taraxacum officinale on carbon tetrachloride induced liver toxicity in mice. Acta Biologica Hungarica, 61(2), 175-190. Retrieved from https://akjournals.com/view/journals/018/61/2/article-p175.xml

(26) Blumenthal, M., Busse, W. R., & Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte. (1998). The complete German Commission E monographs. American Botanical Council.

(27) Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P., Maipas, S., Kotampasi, C., Stamatis, P., & Hens, L. (2016). Chemical Pesticides and Human Health: The Urgent Need for a New Concept in Agriculture. Frontiers in public health, 4, 148. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00148