Andrew Day

(Professor, MB, ChB, MD, FRACP)

In the last few years, studies have shown that the robustness of our immunity depends to some extent on the diversity of our gut microbiome, and the balance between the “good” and the “bad” bacteria.

This is where probiotics, from food and supplements, are being more extensively researched to have a better understanding of their effects and benefits on certain health conditions, in adults and children.

What are probiotics?

Probiotics are live organisms (bacterial or fungal) that can produce beneficial effects when taken.[1] Probiotics must also be able to survive the long and hazardous journey through the gut and be able to be taken safely.

Most probiotics were originally isolated from humans

While many probiotics are bacteria (e.g. Lactobacillus reuteri), there are other forms, such as probiotic yeasts (e.g. Saccharomyces boulardii).

How do probiotics differ from prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics?

Prebiotics are compounds that, upon administration, promote an increased growth of beneficial organisms in the gut.

Synbiotics are a combination of a prebiotic with a probiotic agent.

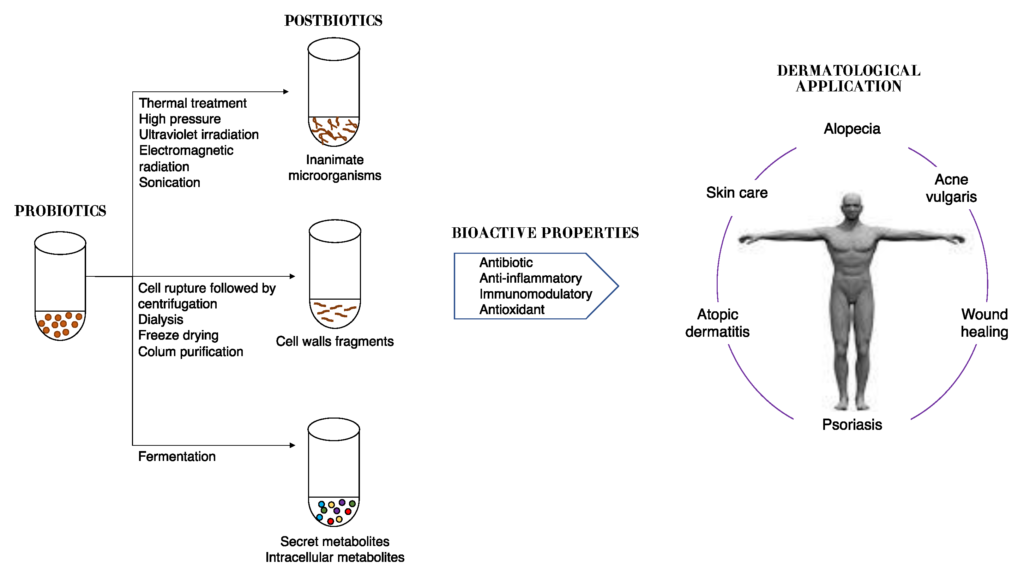

Postbiotics are products that include inactivated (no longer alive) probiotic organisms along with active compounds produced by the probiotic organism that together have beneficial effects.

The concept of beneficial organisms in foods was first developed by a scientist Dr Elie Metchnikoff, after his observations of positive health outcomes associated with regular ingestion of yoghurt. The concept of probiotic agents has changed extensively over time, with the current definition reflecting a consensus made in 2014.[1]

Some current yoghurt products may contain added probiotic strains able to generate health benefits.

There are many other fermented foods available (e.g. kefir, kombucha, kimchi and sauerkraut) but these do not always have sufficient active agents present to be considered to have probiotic effects.

What is the intestinal microbiome?

The intestinal microbiome is the collective term for the billions of organisms that live inside our gut. All of us have many millions of organisms living in our gastrointestinal (GI) tract.[2,3] Although most of these organisms are bacteria, there are other types of organisms there as well such as yeasts and viruses.

It is generally accepted that we start to acquire these organisms during and following birth, with movement through the birth canal being one key initial event.

From the moment of birth onwards, there is continued development of the intestinal microbiome over the following 3-4 years.

Factors that influence this process include:

- the method of birth delivery

- exposure to environmental sources (including mother’s skin)

- breast feeding

- time and pattern of weaning

- infections

- exposure to antibiotics

The pattern of the intestinal microbiome is stable by the late preschool years and then is essentially maintained throughout life.

Within this community of organisms there are interactions and collaborations that enable a wide diversity of organisms to work together. These organisms also interact closely with lining cells of the gut and assist in the priming and development of the immune system.[2,3,4]

The organisms present within the intestinal microbiome have many beneficial effects for our health and well-being.

These include the production of various vitamins and compounds (such as short chain fatty acids) that we use and require for daily functioning.

Our resident bacteria also have various mechanisms that help to stop new bugs/pathogens joining in and spreading.

How do probiotics work and why are they important for our health?

Probiotics are the “good guys”. There are numerous ways that they can provide beneficial effects, such as:

- helping to digest or break down foods

- breaking down some medicines

- contributing to resistance to “bad bugs” (this helps to stop these invaders from taking up residence in the gut)

- restoring balance in the microbiome

- interacting and communicating with the lining cells of the gut

- some probiotics also produce compounds that contribute to their benefits.[5]

These interactions can enhance the protective effects of the lining cells of the gut and enable immune cell function, contributing to maintenance of health.

Health benefits of probiotics — what does the research say?

Probiotics have been considered or evaluated as interventions for numerous conditions affecting many of the body’s organ systems. Benefits have been shown or suggested in many of these studies.[6,7,8]

Various probiotic agents at different doses have been used across the many reported studies. This does make generalisation difficult and limits the ability to make firm recommendations in some areas. In addition, further and ongoing studies can lead to new findings or sometimes lead to changes in recommendations.

Acute gastroenteritis

Acute gastroenteritis (a tummy bug) is typified by the onset of vomiting and diarrhoea, with symptoms lasting less than two weeks.

A number of international and national guidelines have recommended the use of probiotics for acute gastroenteritis as an adjunct to general cares that focus on maintaining or restoring hydration.[9,10,11,12,13]

Most guidelines suggest Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG or Saccharomyces boulardii. Lactobacillus reuteri may also have a role, but the supportive data is weaker.

Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea (AAD)

The administration of antibiotics, especially broad-spectrum agents, can lead to diarrhoea. One severe form of this is the development of Clostridioides Difficile Infection (CDI). While most AAD is annoying, CDI can be fatal in some settings.

Using probiotics during a course of antibiotics can prevent AAD

One assessment of a large number of studies involving children who were receiving antibiotics showed that those who also received probiotics had approximately half the rate of AAD.[14,15,16]

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG or Saccharomyces boulardii can be considered for this indication.

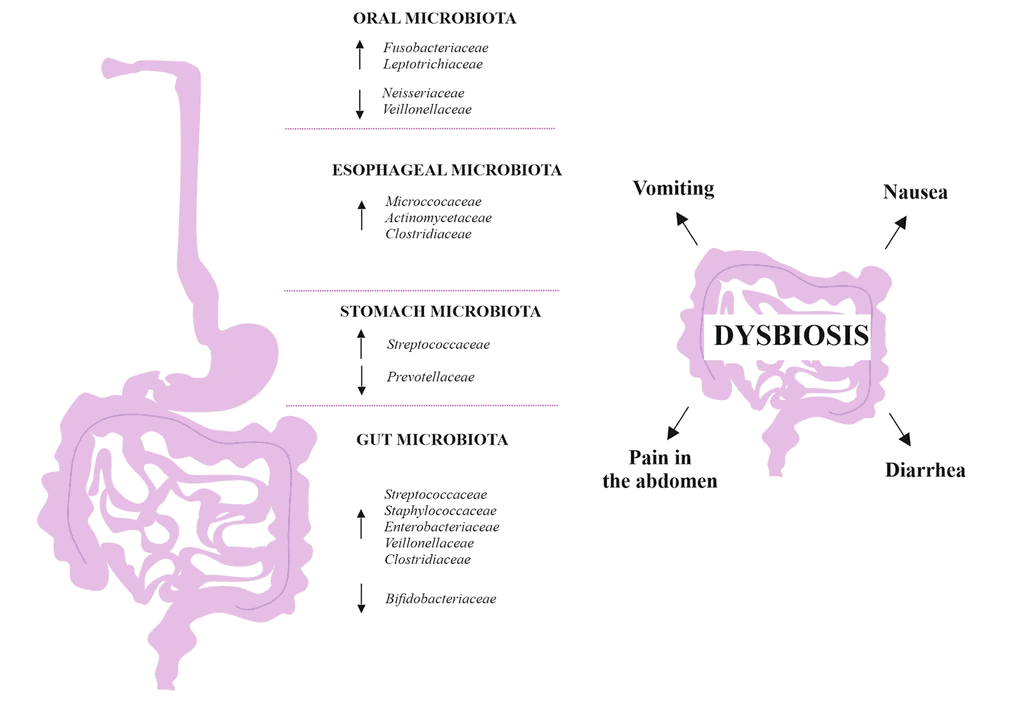

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is a condition whereby there is excessive growth of particular organisms within the small bowel.

This overgrowth can lead to various gastrointestinal symptoms such as:

- diarrhoea

- bloating

- pain

- malabsorption

SIBO can be managed with various interventions, once any remediable underlying cause has been excluded or corrected.

SIBO treatments include dietary changes or antibiotics

Probiotics may also have a role in the management of SIBO in children, although some studies suggest enhanced outcomes when these are combined with antibiotics.[17,18,19]

Skin health

Several studies suggest that probiotics and postbiotics may have benefits in the prevention or management of skin conditions, such as acne and eczema.[20,21,22] One of the studies showed that a combination of probiotics was just as effective as an antibiotic for the treatment of acne in adolescents.

Topical application along with oral ingestion (with modulation of the intestinal microbiome) have both been evaluated. In addition, prenatal administration of probiotics to mothers has been shown in some studies to reduce rates of atopic dermatitis (eczema) in their offspring.

Obesity

A number of changes in the patterns of the microbiome have been observed in individuals who are obese compared to others with normal body weight.

Consequently, there have been a number of studies evaluating probiotics as a tool to help in the management of obesity. One recent overview of four separate studies, that included 206 children who were overweight or obese, showed that probiotics resulted in changes in a number of hormones associated with appetite and weight control.[22] However, probiotics did not have an overall effect upon weight in these studies.

In contrast, an earlier clinical trial that involved the administration of a mixture of probiotics, prebiotics and extra vitamins led to a reduction in weight and waist circumference along with improvements in lipid levels.[23]

While this is an intriguing and promising field, there are not yet clear guidelines to indicate probiotics for obesity.

Dysbiosis secondary to night shift work

There are clear associations between shift work and alterations in the intestinal microbiome. Some studies have suggested that probiotics may help to correct these changes.[24]

In particular, several studies have suggested less anxiety, stress and fatigue in those having probiotics. One study showed that none of a group having a probiotic reported feeling sick compared to a third of those not having the probiotic. The available data is not yet robust enough to guide clear recommendations.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Irritable bowel syndrome is a common condition in men and women. IBS can lead to bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhoea or constipation. Managing stress and dietary changes can be helpful for some people with IBS.

Many studies have looked at the effects of different probiotics in people with IBS.

One large assessment of 72 clinical trials of probiotics in people with IBS was published recently.[25] Overall, this work showed that probiotics resulted in improved quality of life and reduced pain and symptoms.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

The diseases termed inflammatory bowel disease are characterised by inflammation in various sections of the gut.

IBD is linked with changes in the intestinal microbiome (the term dysbiosis has been used), which is considered to be one of the key components of the cause of IBD.

There are numerous preclinical and animal studies showing a decrease in inflammation achieved with probiotics. However, human studies have not yet clearly demonstrated benefits for all types of IBD.

Mental health

There are clear links between the intestinal microbiome and disorders of mental health, such as depression and anxiety.[26] However, probiotic guidance has not yet been established for this indication.

RELATED — Introduction to: Depression

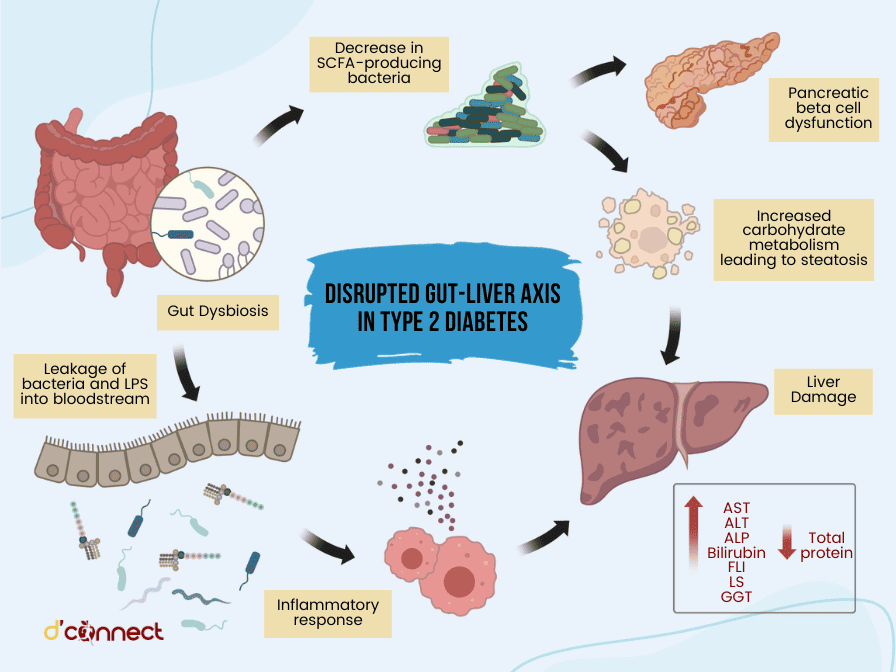

High cholesterol and metabolic syndrome (MALFD)

Elevated cholesterol can commonly be seen, especially with increasing age. This can contribute to complications including heart disease.

A number of studies have shown that probiotics can reduce blood cholesterol levels, in individuals with low, normal, or high levels.

This effect is attributed to increased activity of an enzyme in the gut that breaks down cholesterol from bile, leading to more being excreted in the stool and less being reabsorbed.

These effects have also been shown to be beneficial in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A number of probiotic agents have been evaluated for this indication, with some variance between strains.[27,28,29]

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

Multi-agent probiotic preparations appear to have superior benefits. Some probiotics shown to have benefit are Bifidobacterium lactis HN019, Saccharomyces boulardii, and the combination of Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 with Lactobacillus plantarum KY1052.

Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC)

NEC is a potentially serious condition that can occur in newborn babies, especially pre-term infants.

Following a series of research studies, probiotic supplementation is now undertaken on a routine basis in many neonatal intensive care units. While this intervention is associated with reductions in the rates of NEC, it also leads to faster establishment of full feeding and lower infectious complications.[30,31]

Infant colic

Colic is a common cause of distress in infants, typically having onset from 6-8 weeks of age with resolution over the subsequent months.

Alterations in the intestinal microbiome may affect gut motility and gas production, leading to crampy pain. Lactobacillus reuteri may have a role for the management of colic in infants.[32]

Cystic fibrosis (CF)

Cystic fibrosis is a multi-system disorder that particularly impacts upon lung function.

Inflammation of the gut is seen in individuals with CF and contributes to altered growth and impaired lung function. Some studies have suggested that probiotics might improve gut inflammation, consequently leading to enhanced outcomes.

Further studies in Australasia are ongoing and should further inform this indication for probiotics.

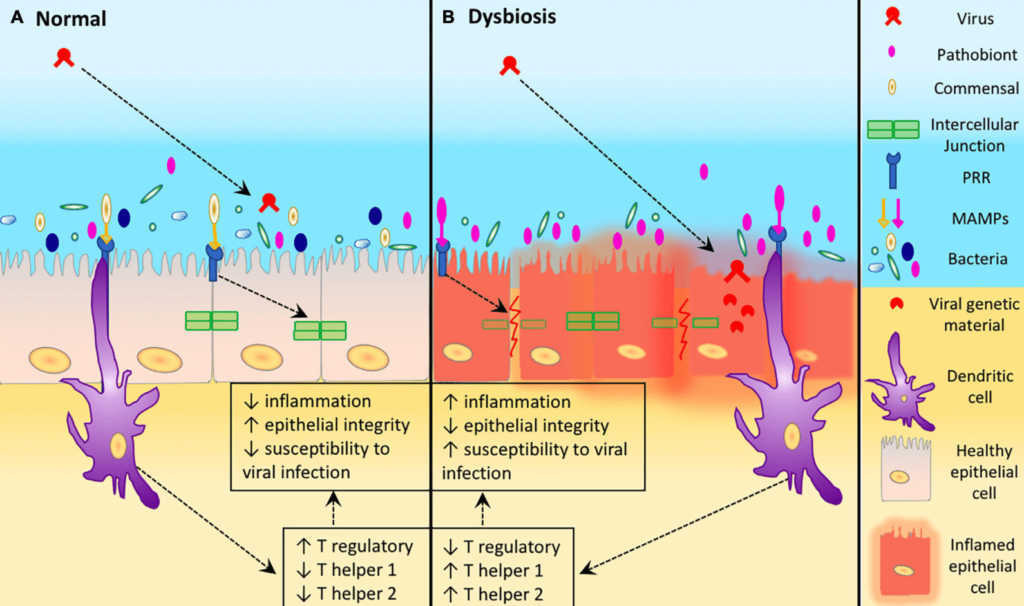

Upper respiratory tract infections

Various infections of the upper part of the respiratory tract are common: most are due to viruses. These infections are typically self-limited but can lead to complications such as sinusitis.

(B) Dysbiosis in the URT leads to an increase abundance of a pathobiont, resulting in increased inflammation, reduced epithelial integrity. This leads to host cell damage which increases the susceptibility of host URT to viral infection.

Source: Nesbitt, H. Manipulation of the Upper Respiratory Microbiota to Reduce Incidence and Severity of Upper Respiratory Viral Infections: A Literature Review. (2021)

Some studies report no benefits for the prevention of these respiratory illnesses, but others indicate reductions in symptoms, time away from school or work and antibiotic usage.[33]

What are the possible risks of probiotics?

In some settings probiotics may lead to side-effects or adverse outcomes.

Some people can have gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea or loose motions for example) when starting probiotics. These mild symptoms usually resolve over a week or so and would not be seen as a reason to stop the probiotic.

Less commonly, probiotics may move through the surface of the gut and reach the bloodstream (translocate) where they could then cause complications.[34,35,36] Although well described, translocation occurs only rarely.

To balance this risk, probiotics are also shown to improve the integrity of the gut lining (making it less permeable), which would lead to reduced risk of translocation.

Issues that could increase the risk of translocation include:

- damage or disruption to natural defences on the surface of the gut

- the setting of immunodeficiency (reduced ability to fight infections, such as secondary to chemotherapy or with HIV infection) or the presence of an indwelling central venous catheter

Translocation may be more likely to occur in the very young or in older adults.

Some particular probiotics can produce a compound called D-lactic acid, which in the relevant setting can lead to acidosis and sedation.

Adults can usually break down this compound, but younger children have reduced capacity to do so.

Consequently, this can particularly be an issue in young children with short gut syndrome if they have an overgrowth of particular bacteria or perhaps if they receive a specific probiotic that is able to produce this compound.[37]

While there are reports of allergic reactions to probiotic preparations, these are rare.

There are also reports of transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from a probiotic strain to a potential pathogen in the gut, but again this is thought to be an uncommon event.

Who should not take probiotics?

There are a few situations where the potential risks of taking a probiotic may be greater than the benefits. While probiotics should be avoided completely in some of these situations, they can be used with caution in other settings.

Generally, however, it is important that people discuss with their doctor whether or not it is safe for them to have a particular probiotic.

Probiotics should be avoided in immunocompromised

Some examples of immunocompromised states are:

- underlying congenital defects in responding to or fighting infections

- during or following chemotherapy

- during or following the use of other drugs that impair immune responses (e.g. corticosteroids)

- after major surgery or in intensive care settings

Having a central venous catheter (an indwelling venous catheter sited in a large vein) could also increase the risk of side-effects associated with probiotics.

One study noted an increased death rate associated with probiotics in people with severe pancreatitis: however, the design of this study has been criticised. Other work has shown that probiotics do have some benefits in pancreatitis.[38]

A North American consensus document reflected that there was little evidence for their use in children with pancreatitis.[39]

Related Questions

1. When is the best time to take probiotics?

Anytime of the day is fine. However, probiotics should not be taken with hot drinks or meals.

Probiotics also should not be taken at the exact same time as antibiotics.

2. Should probiotics be refrigerated?

Most probiotic preparations require refrigeration to maintain the potency of the organisms.

3. Should children take probiotics?

A relevant probiotic strain can be given to children as well as adults.

4. Should I take probiotics while taking antibiotics?

When taking probiotics alongside antibiotics, the probiotics should be taken at a different time from the antibiotics (at least two hours apart).

Also, it is considered best to continue with probiotics for at least one week after the antibiotic course has finished.

5. Do probiotics make you gain weight?

Probiotics will not lead to weight gain.

Conclusions

Probiotics have been considered and evaluated in many different settings. While there is strong data for several indications for probiotics, other data is lacking or unclear.

Furthermore, many different agents have been considered in various studies – the benefit seen with one strain of probiotic may not be seen with another strain.

The best evidence for probiotics use is for acute gastroenteritis, antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and upper respiratory tract infections.

In many of these settings, further prospective large-scale clinical trials are required to elucidate the actual benefits of probiotics.

If you have any questions, feel free to ask us in the comments below.

Andrew has been helping children with gastrointestinal problems for more than two decades.

After completing his medical and basic paediatric training in New Zealand, Andrew headed overseas for further specialist training. He spent three years at Sick Kids Hospital in Toronto, Canada, with clinical and research fellowship years.

After completing his fellowship, Andrew took up a position at the University of New South Wales and Sydney Children’s Hospital (in Sydney, Australia) as an academic paediatric gastroenterologist. During this time, he established his research career and further developed his clinical expertise.

In 2009, he returned to New Zealand to an academic position at University of Otago Christchurch and a clinical position as paediatric gastroenterologist at Christchurch Hospital. Since then, he has also maintained ongoing positions in Sydney. He combines teaching activities and extensive research endeavours with his ongoing clinical roles. Andrew assesses and looks after children and adolescents with a variety of conditions affecting the gut, liver and nutrition.

Andrew’s interests and expertise focus especially on the intersections between nutrition, the intestinal microbiome and health. The effects of diet, nutrition and environmental factors upon the intestinal microbiome are increasingly recognised as important and relevant to overall well-being and to the development of numerous disorders of gut health and of other body systems. Furthermore, nutritional interventions appear to be equally relevant to the management of many of these conditions. Much of Andrew’s time is spent trying to advance our understanding of these links.

When not stuck in the clinic, ward, office or lab, Andrew greatly enjoys getting out walking in or around the Port Hills.

References

(1) Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G. et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 11: 506–514.

(2) Brody H. The gut microbiome. Nature. 2020; 577: S5

(3) Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017; 474: 1823–1836. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5433529/

(4) Wong E, Lui K, Day AS, Leach ST. Manipulating the neonatal gut microbiome: current understanding and future perspectives. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022;107:346-350. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354135927_Manipulating_the_neonatal_gut_microbiome_current_understanding_and_future_perspectives

(5) Kechagia M, Basoulis D, Konstantopoulou S, Dimitriadi D, Gyftopoulou K, Skarmoutsou N, Fakiri EM. Health Benefits of Probiotics: A Review. ISRN Nutr. 2013; 2013: 481651. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4045285/

(6) AGA Technical Review on the Role of Probiotics in the Management of Gastrointestinal Disorders. Preidis GA, Weizman AV, Kashyap PC, Morgan RL. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:708-738.e4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8018518/

(7) Cameron D, Hock QS, Kadim M, Mohan N, Ryoo E, Sandhu B, Yamashiro Y, Jie C, Hoekstra H, Guarino A. Probiotics for gastrointestinal disorders: Proposed recommendations for children of the Asia-Pacific region. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7952-7964.

(8) NASPGHAN Nutrition Report Committee; Michail S, Sylvester F, Fuchs G, Issenman R. Clinical efficacy of probiotics: review of the evidence with focus on children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:550-7.

(9) Leung AK, Hon KL. Paediatrics: how to manage viral gastroenteritis. Drugs Context. 2021;10:2020-11-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8007205/

(10) Szajewska H, Mrukowicz JZ. Probiotics in the treatment and prevention of acute infectious diarrhea in infants and children: a systematic review of published randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33 Suppl 2:S17-25

(11) Fagnant HS, Isidean SD, Wilson L, Bukhari AS, Allen JT, Agans RT, Lee DM, Hatch-McChesney A, Whitney CC, Sullo E, Porter CK, Karl JP. Orally Ingested Probiotic, Prebiotic, and Synbiotic Interventions as Countermeasures for Gastrointestinal Tract Infections in Nonelderly Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr. 2023;14:539-554.

(12) Salazar-Parra MA, Cruz-Neri RU, Trujillo-Trujillo XA, Dominguez-Mora JJ, Cruz-Neri HI, Guzmán-Díaz JM, Guzmán-Ruvalcaba MJ, Vega-Gastelum JO, Ascencio-Díaz KV, Zarate-Casas MF, González-Ponce FY, Barbosa-Camacho FJ, Fuentes-Orozco C, Cervantes-Guevara G, Cervantes-Pérez E, Cervantes-Cardona GA, Cortés-Flores AO, González-Ojeda A. Effectiveness of Saccharomyces Boulardii CNCM I-745 probiotic in acute inflammatory viral diarrhoea in adults: results from a single-centre randomized trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:229.

(13) Ansari F, Pashazadeh F, Nourollahi E, Hajebrahimi S, Munn Z, Pourjafar H. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: The Effectiveness of Probiotics for Viral Gastroenteritis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2020;21:1042-1051.

(14) Goldenberg JZ, Lytvyn L, Steurich J, Parkin P, Mahant S, Johnston BC. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(12):CD004827

(15) Yang Q, Hu Z, Lei Y, Li X, Xu C, Zhang J, Liu H, Du X. Overview of systematic reviews of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1153070 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1153070/full

(16) Dinleyici M, Vandenplas Y. Clostridium difficile Colitis Prevention and Treatment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1125:139-146

(17) Kiecka A, Szczepanik M. Proton pump inhibitor-induced gut dysbiosis and immunomodulation: current knowledge and potential restoration by probiotics. Pharmacol Rep. 2023;75:791-80 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43440-023-00489-x

(18) Nickles MA, Hasan A, Shakhbazova A, Wright S, Chambers CJ, Sivamani RK. Alternative Treatment Approaches to Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review. J Altern Complement Med. 2021;27:108-119

(19) Zhong C, Qu C, Wang B, Liang S, Zeng B. Probiotics for Preventing and Treating Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Current Evidence. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:300-311.

(20) Vieira De Almeida C, Antiga E, Lulli M. Oral and Topical Probiotics and Postbiotics in Skincare and Dermatological Therapy: A Concise Review. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1420. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/11/6/1420

(21) Sun S, Chang G, Zhang L. The prevention effect of probiotics against eczema in children: an update systematic review and meta-analysis J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:1844-1854.

(22) Li Y, Liu T, Qin L, Wu L. Effects of probiotic administration on overweight or obese children: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Transl Med. 2023;21:525

(23) Safavi M, Farajian S, Kelishadi R, Mirlohi M, Hashemipour M. The effects of synbiotic supplementation on some cardio-metabolic risk factors in overweight and obese children: a randomized triple-masked controlled trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2013;64:687-93

(24) Lopez-Santamarina A, Del Carmen Mondragon A, Cardelle-Cobas A, et al. Effects of Unconventional Work and Shift Work on the Human Gut Microbiota and the Potential of Probiotics to Restore Dysbiosis. Nutrients. 2023;15:3070. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/15/13/3070

(25) Chen M, Yuan L, Xie CR, Wang X-Y, Feng S-J, Xiao X-Y, Zheng H. Probiotics for the management of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and three-level meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2023, August 11.

(26) Schrodt C, Mahavni A, McNamara GPJ, Tallman MD, Bruger BT, Schwarz L, Bhattacharyya A. The gut microbiome and depression: a review. Nutr Neurosci. 2023;26:953-959.

(27) Barber TM, Hanson P, Weickert MO. Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and the Gut Microbiota. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2023;52:485-496.

(28) Memon H, Abdulla F, Reljic T, Alnuaimi S, Serdarevic F, Asimi ZV, Kumar A, Semiz S. Effects of combined treatment of probiotics and metformin in management of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;202:110806.

(29) Al-Najjar Y, Arabi M, Paul P, Chaari A. Can probiotic, prebiotic, and synbiotic supplementation modulate the gut-liver axis in type 2 diabetes? A narrative and systematic review of clinical trials. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1052619. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9751375/

(30) Sharif S, Meader N, Oddie SJ, Rojas-Reyes MX, McGuire W. Probiotics to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very preterm or very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Jul 26;7(7):CD005496.

(31) Barbian ME, Patel RM. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis: Where do we stand? Semin Perinatol. 2023;47:151689.

(32) Shirazinia R, Golabchifar AA, Fazeli MR. Efficacy of probiotics for managing infantile colic due to their anti-inflammatory properties: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021;64:642-651. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8650819/

(33) Zhao Y, Dong BR, Hao Q. Probiotics for preventing acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;8: CD006895

(34) Kullar R, Goldstein EJC, Johnson S, McFarland LV. Lactobacillus Bacteremia and Probiotics: A Review. Microorganisms. 2023;11:896.

(35) Hefter Y, Powell L, Tabulov CE, Sadler ED, Campos J, Hanisch B. An 11-Year Review of Lactobacillus Bacteremia at a Pediatric Tertiary Care Center. Hosp Pediatr. 2023 May 19;e2022006892.

(36) Acuna-Gonzalez A, Kujawska M, Youssif M, Atkinson T, Grundy S, Hutchison A, Tremlett C, Clarke P, Hall LJ. Bifidobacterium bacteraemia is rare with routine probiotics use in preterm infants: A further case report with literature review. Anaerobe. 2023;80:102713.

(37) Martínez Navarro G, Polo B, Donat E, Masip E, Pacheco J, Adell A, Ortega P, Ribes-Koninckx C. Encephalopathy in short bowel syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2023;115:47.

(38) Hou X, Yang J, Zhao Z, Liu L. A meta-analysis of the effects of probiotics on acute pancreatitis Asian J Surg. 2023;46:3885-3889.

(39) Abu-El-Haija M, Kumar S, Quiros JA, Balakrishnan K, Barth B, Bitton S, et al. Management of Acute Pancreatitis in the Pediatric Population: A Clinical Report From the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Pancreas Committee J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:159-176. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5755713/