Joyce Leung

(Research Assistant, BFoodTech)

Jump to:

Marine farming and blue economy are the next step in sustainability and development of functional foods.

Seaweed are a type of algae and are essential in marine ecosystems. Apart from being responsible for absorbing UV radiation and carbon dioxide, and producing oxygen, they are extremely rich in antioxidants and vitamins. Seaweed also have a high concentration of protein and energy content.

There are 3 main groups of seaweed (green, red and brown) that together number over 9000 different types, with the largest in size being the brown seaweed.

We will be looking at the abundance of benefits for consuming and cultivating seaweed, but let’s first start with understanding the purpose of seaweed in our oceans.

The purpose of seaweed in oceans and waterways

Seaweeds are essential in marine ecosystems. Being the first organism in marine food chains, seaweeds are treated as food sources for animals to provide rich nutrients and energy content.

Beds of seaweed, such as kelp forests, serve as a shelter or habitat for marine life such as lobster and mussels.[1]

Seaweeds have been studied to understand their potential as a bioremediation component to reduce eutrophication (excess nutrients found in the environment) in aquaculture systems.

It was found that Caulerpa sertularioides (a type of green algae) was most efficient in phosphorus absorption from seawater.

Two species of Rhodophyceae (Acanthophora muscoides and Hydropuntia edulis) were detected to contain the most UV-absorbing compounds.

These compounds contribute greatly to the reduction in the absorption of UV radiation into aquaculture water.[2]

Most of the oxygen we breathe comes from organisms in the ocean

Seaweeds converts sunlight into chemical energy, and produce oxygen for human consumption, while at the same time using up carbon dioxide, and detoxifying and purifying the water.[2]

Types of seaweed

Seaweeds are marine algae. It was empirically distinguished since the mid-nineteenth century based on the visual color of seaweed species found at various latitudes and depths of water:

- Green (found in shallower salt and fresh waters)

- Brown (exclusively found in salt waters)

- Red (found in deeper depths of up to 250m).

However, differences among these three groups are more than just color. In addition to the pigmentation, they differ considerably in many structural and biochemical features such as the composition of cell walls, presence/absence of flagella, the ultrastructure of mitosis, connections between adjacent cells, and the fine structure of the chloroplasts.[3]

Green seaweeds

Green color pigments are from chlorophyll a and b. As mentioned, green seaweeds are usually found in the intertidal zone (between the high and low watermarks) and in shallow water where there is plenty of sunlight.

About 140 species have been recorded around the coast in NZ.[4]

Examples of green seaweed include:

- Sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca), which forms bright green sheets up to 30cm in diameter

- Gut weed (Enteromorpha intestinalis), a tubular green seaweed that favors high-nutrient sites

- Sea rimu (Caulerpa brownii), edible and resembles the foliage of the large tree rimu.

In terms of green seaweed structure, it contains high levels of chlorophyll and high-quality fibers.

Brown seaweeds

Brown seaweed ranges from medium to giant-sized seaweeds, and are particularly growing at depths below the greens and above the reds.

The brown color of these algae results from the dominance of the xanthophyll pigment fucoxanthin, which masks the other pigments such as Chlorophyll a and c (there is no Chlorophyll b), beta-carotene, and other xanthophylls.

The largest brown seaweeds are known as kelps

Neptune’s necklace (Hormosira banksii) is commonly found around the rocky shore. Its branching chains of water-filled bladders help it withstand periods of exposure when the tide goes out.

Brown seaweed is renowned for its high mucilage production ability compared to its two counterparts. Particularly, Gummy weed (Splachnidium rugosum), a type of brown seaweed, would profuse (emit) large quantities of sticky slime or mucilage when touched that protect itself from drying out.

Red seaweeds

The red colour of these algae results from the pigments phycoerythrin and phycocyanin. There are 550 species of red seaweed, making them the largest group.[4] In the clear waters around the Kermadec Islands, red seaweeds may be found at depths greater than 200 meters.

In the nutrient-rich coastal waters of New Zealand’s main islands, very few survive below 25 meters.

One of the best-known reds is the edible Karengo (Porphyra species), which grows on rocks near high tide levels and resembles sheets of light purple cellophane. It is a close relative of the Japanese nori, used for sushi.

Another familiar red seaweed is the fern-like Agar weed (Pterocladia lucida), which has been harvested for agar production in New Zealand since 1943. The coralline seaweeds are a group of reds that deposit calcium carbonate in their cell walls, forming pink skeletons or paint-like crusts on coastal rocks.

RELATED — Calcium (for healthy bones, teeth and heart)

Scientists have discovered that some crust-forming seaweeds release chemicals that encourage pāua (abalone) larvae to settle and mature.

Red seaweeds are said to be high in prebiotic fibers and anti-viral, anti-fungal, anti-parasitic, antiseptic, and anti-inflammatory properties.[5]

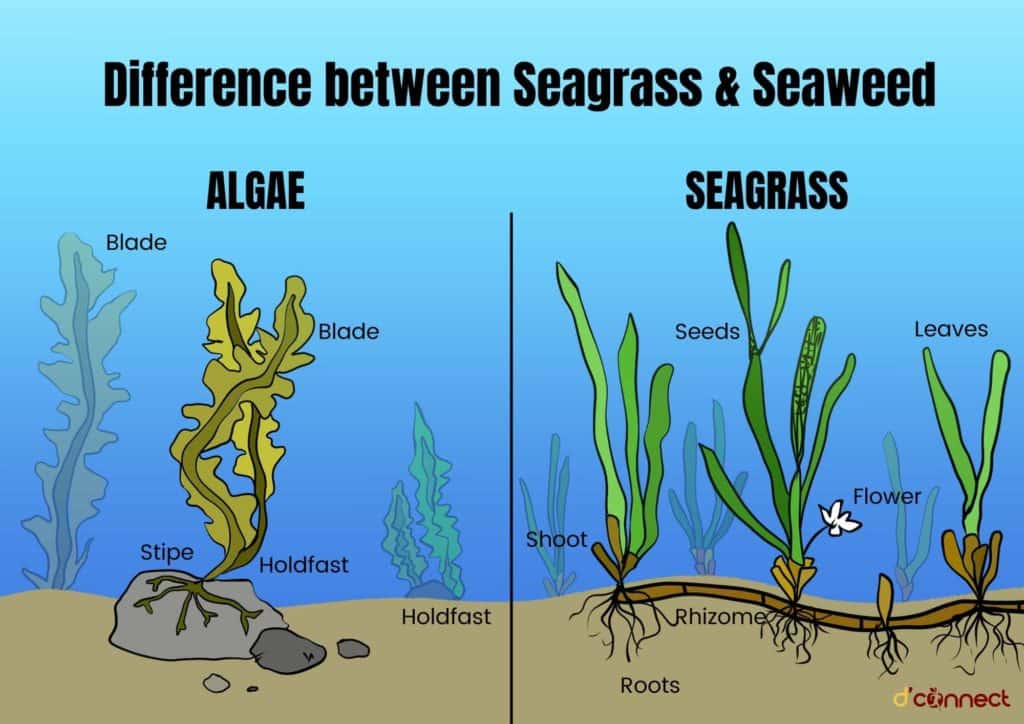

What is the difference between seaweed, seagrass and algae

This section aims to debunk some misused terms. Even under certain scenarios, “algae” and “seaweed” could be used interchangeably, yet, there are still distinct differences among them.

Difference between algae and seaweed

In short, seaweed is a type of algae. Yet, not all algae could be characterized as seaweed. The two have major differences, in terms of history, the range of species, habitats, and even the cellular structure.

Algae are chlorophyll-containing organisms commonly found in aquatic environments such as marine bodies, sea, and even freshwater bodies.

Seaweed are plant-like organisms that attach themselves to rocks and other hard substances in an aquatic environment. Algae’s size could be as tiny as microscopic-sized single cells, yet, seaweed could be large enough and clearly seen.[6]

Difference between seagrass and seaweed

Seagrass can easily be confused with seaweed. However there are many important differences between the two, particularly as seagrass acts in a similar way to land-grown plants.

Seagrasses are considered to be vascular plants and have roots, stems, and leaves just like land-plants. However, seaweed are multicellular algae and have little or no vascular tissues.

In terms of structural differences, algae have spores and do not flower or produce fruit, while seagrasses have seeds and fruit. In contrast to seagrasses, algae do not have a true root system (they have holdfasts) and do not have veins that carry molecules around the plant.

In terms of reproduction methods, seagrass can reproduce through sexual or asexual methods as it is divided into females and males.

In sexual reproduction, the plants produce flowers and transfer pollen from the male flower to the ovary of the female flower. Seaweed differs as it can only conduct asexual reproduction through fragmentation or division.[7]

Difference between spirulina, chlorella and seaweed

Chlorella and spirulina are the most popular algae supplements on the market. While both boast an impressive nutritional profile and similar health benefits, they have several differences. Their most notable nutritional differences lie in their calorie, vitamin, and mineral contents.

RELATED — Zinc: For immunity, skin health and libido

A study that analyzed the fatty acid contents of these algae found that chlorella contains more omega-3 fatty acids, while spirulina (image below) is higher in omega-6 fatty acids.[8]

Chlorella is a genus of about thirteen species of single-celled green algae belonging to the division Chlorophyta.

The cells are spherical in shape, about 2 to 10 μm in diameter, and are without flagella. Their chloroplasts contain the green photosynthetic pigments chlorophyll-a and -b. Below we can see the image of chlorella and the visual differences between chlorella and spirulina.

In ideal conditions cells of chlorella multiply rapidly, requiring only carbon dioxide, water, sunlight, and a small number of minerals to reproduce. While spirulina is the most ancient, filamentous, photosynthetic seaweed that uses water as an electron donor in photosynthesis giving out oxygen.[9]

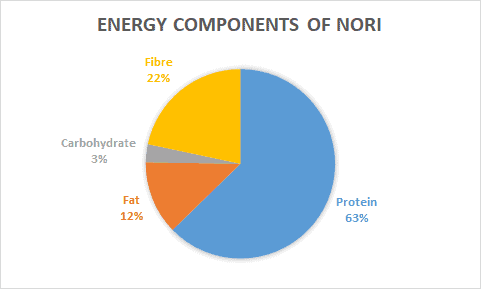

Nutritional Value of Seaweed

Take the most common consumed seaweed as an example: Nori for sushi (9g per serving)

Vitamins and Minerals in seaweed

Macronutrients | Quantity per serving | Quantity per 100g |

Weight (g) | 9.00g | 100.00g |

Energy (kJ) | 113.94kJ | 1266.00kJ |

Protein (g) | 4.20g | 46.70g |

Nitrogen conversion factor | 6.25 | 6.25 |

Total fat (g) | 0.39g | 4.30g |

– Saturated fat (g) | 0.08g | 0.88g |

– Polyunsaturated fat (g) | 0.21g | 2.32g |

– Monounsaturated fat (g) | 0.03g | 0.32g |

Carbohydrate (g) | 0.21g | 2.30g |

Sugars (g) | 0.03g | 0.30g |

Starch (g) | 0.18g | 2.00g |

Vitamins |

|

|

Niacin (mg) | 0.86mg | 9.50mg |

Niacin equivalents (mg) | 1.54mg | 17.15mg |

Vitamin C (mg) | 26.10mg | 290.00mg |

Total folate (µg) | 126.00µg | 1400.00µg |

Total vitamin A equivalents (µg) | 105.03µg | 1167.00µg |

Beta carotene equivalents (µg) | 630.00µg | 7000.00µg |

Minerals |

|

|

Sodium (mg) | 42.30mg | 470.00mg |

Potassium (mg) | 261.00mg | 2900.00mg |

Magnesium (mg) | 28.80mg | 320.00mg |

Calcium (mg) | 27.90mg | 310.00mg |

Phosphorus (mg) | 70.20mg | 780.00mg |

Manganese (µg) | 315.00µg | 3500.00µg |

Sulphur (mg) | 171.00mg | 1900.00mg |

Iodine (µg) | 198.00µg | 2200.00µg |

Aluminium (µg) | 315.00µg | 3500.00µg |

RELATED — Magnesium: For a great night of sleep

Sea vegetables are also rich in vitamins B (folate) and C. They are the richest foods in natural organic iodine, besides, seaweeds can offer one of the very few plant-based sources of Vitamin B12 that support vegans and vegetarians, especially those who avoid animal protein.

Protein in Seaweed

High protein content per serving of up to 4.2g protein / 9g of seaweed. While taking beef sirloin as an example, such red meat would only provide 2.7g of protein/ 9g. Red seaweeds tend to offer the highest protein of all seaweeds.[10]

Carbohydrates in Seaweed

Seaweeds also contain exceptional saccharides in the form of glyconutrients (for example in Agar & carrageenan) and complex sugars (like Mannitol). Seaweed carbohydrates are slow-releasing sugars in the form of fibers, supplying plenty of energy with few calories.

The fibers in seaweed can divided into soluble and insoluble forms, and both are able to bind water or mineral cations, and may be used by colonic microflora, as fermentable substrates, to provide prebiotic benefits & facilitate the binding, lubrication and evacuation of toxins.[10]

Fatty Acids in Seaweed

Ocean vegetables contain fatty acids with a favorable ratio of Omega-3, antioxidants and phytonutrients.[10]

Health Benefits of Seaweed

Some of the health benefits of seaweed are:

- Supporting gut health

- Improving thyroid function

- Cleansing and detox

- Maintaining healthy weight

- Boosting immune system

- Relieving hypertension

- Reducing chronic inflammation

- May have anti-cancer properties

- Good source of antioxidants

Supporting gut health

Algae tend to contain high amounts of prebiotics such as carrageenans, agars, fucoidans, which may make up 23–64 percent of the algae’s dry weight. The non-digestible fiber in seaweed can help feed the gut’s bacteria.

Adding algae to the diet may be a simple way to provide the body with plenty of gut-healthy prebiotic fiber, and from what we know about the gut microbiome, whenever the good bacteria flourish, the bad ones naturally diminish, hence we’re less likely to experience gastrointestinal upset which in turn can help with issues such as constipation or diarrhea.[11]

Improving thyroid function

Iodine deficiency can result in adverse thyroidal health consequences. Seaweed has a high concentration of iodine, an essential nutrient for thyroid function. Iodine is the precursor for the production of thyroid hormone.

An individual’s ability to produce adequate levels of thyroid hormones is dependent on iodine stores built up and maintained over a period of time.[12]

Cleansing and Detox

Seaweeds have unique compounds which attract toxins, and some of them, like Agar and Irish moss, also have a gentle laxative effect, helping the body to eliminate waste more efficiently. These stimulate the liver, kidney, skin, and intestines to drive stored toxins out of the body and improve blood circulation.

Chlorophyll presented in all types of seaweed is also a potent cleanser that purifies the bodily fluids, such as blood and lymph, that are transported throughout our body to our organs for better overall health.[13]

Maintaining healthy weight

High iodine content could also help regulate weight and stimulate cellular activity (this in turn, burns fats). The carotenoid fucoxanthin has great commercial value since it is accepted to be helpful in the treatment of obesity.

A 2018 study in rats found that compounds in one type of seaweed may directly reduce markers of type 2 diabetes.[14]

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

Another research led by a team of scientists, Dr Iain Brownlee and Prof Jeff Pearson, have found that dietary fibre in one of the world’s largest commercially-used seaweed could reduce the amount of fat absorbed by the body by around 75%.[15]

Boosting immune system

Nutrients that have been identified as critical for the growth and function of immune cells include vitamin C, vitamin D, zinc, selenium, iron, and protein (including the amino acid glutamine), which are commonly found in seaweed.

RELATED — Vitamin C: Immunity and Collagen booster

A more recent study looked at the effects of taking seaweed supplements in HIV-positive women. Those given 5 grams of spirulina per day developed 27% fewer disease-related symptoms, compared to the placebo group.[16]

Relieving hypertension

ACE-I is a type of enzyme that controls human blood pressure by regulating the volume of fluids in the body. Thus, researchers suggested that to treat hypertension, inhibiting the ACE-I activity is the most promising approach.

Species of seaweed such as E. cava, E. stolonifera were found to be inhibiting at least 50% of ACE-I.[18]

Reducing chronic inflammation

Algae contain a number of anti-inflammatory bioactive compounds such as omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) and chlorophyll a, hence as dietary ingredients, their extracts may be effective in chronic inflammation-linked metabolic diseases.

Researches suggest that the algal lipid extracts examined have the potential to suppress inflammation through inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production and down-regulation of genes involved in a number of inflammatory signaling pathways.[19]

Examples of more well known phenolic compounds are the cannabinoids, the active constituents of cannabis.

May have anti-cancer properties

The b-carotene presented in seaweed is one of the most effective substances to counteract free radicals that alter cells causing cancer. The b-carotene solution applied to oral cancer tumors in hamsters reduced the tumor number and size and in some cases, these disappeared.

RELATED — Prostate Cancer: All you need to know and are afraid to ask

Spirulina extract for example induces the tumor necrosis factor in macrophages, suggesting a possible tumor destruction mechanism.[20,21]

RELATED — How common is Breast Cancer and what are the Risk Factors

Good source of antioxidants

Seaweed contains a wide range of antioxidants, such as vitamins A, C and E, carotenoids and flavonoids. These antioxidants protect our body from cell damage. A lot of research has focused on one particular carotenoid called fucoxanthin. It’s the main carotenoid found in brown algae, such as wakame, and it has 13.5 times the antioxidant capacity as vitamin E.

Fucoxanthin has been shown to protect cell membranes better than vitamin A.[22]

Health Concerns and Risks

The high-fiber content in seaweed can aid digestion but it can also cause digestive discomfort. Each gram of fiber adds up, and several servings of seaweed per day can easily push us over the recommended daily allowance of fiber. Too much fiber can cause bloating, gas and constipation.

People with health issues related to the thyroid should be especially cautious of overconsuming seaweed because of its high iodine content. According to a March 2014 study published in Nature Reviews Endocrinology, excess iodine consumption does not have major consequences in the average person.

However, people with specific risk factors related to thyroid diseases — such as hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism — may find that too much iodine can affect their thyroid function and thyroid medications.[22]

There is concern that seaweed grown on Japanese coasts is contaminated by radioactivity resulting from the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011.[23]

A January 2014 study published in the Journal of Plant Research found contaminated samples of algae. However, researchers do not advise limiting our seaweed intake due to potential radioactive exposure.

Another side effect related to the environment is heavy metal exposure. According to a February 2018 study published in Scientific Reports, red seaweed contains significantly higher levels of copper, nickel, and other metals like arsenic compared to brown seaweed.

Though researchers found heavy metals like lead and mercury, they report the risk level is low. However, they recommend the routine surveillance of metals in seaweed.[24]

Related Questions

1. How much seaweed per day is safe to consume?

On average, the Japanese diet contains around 5-10g of seaweed daily and iodine in the range of 1,000-3,000µg.[25]

Daily seaweed consumption depends a lot on what type of seaweed, since the main danger associated with seaweed is iodine.

The iodine intensity varies across different dietary seaweed species. While the upper limit intake of iodine for adults is 1,100 µg/day, that being said, for the least iodine-intensive seaweed such as Nori (12µg iodine per gram,) we could consume up to 91g (not recommended).[26]

2. Is seaweed farming sustainable?

Sustainability means meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.[27]

Promoting seaweed farming in New Zealand should not pose irreversible effects on environmental, social, and economic aspects.

From an environmental perspective, seaweed cultivation requires zero scarce land, soil and fertiliser, meaning that its farming would pose negligible harm to the environment while giving out enormous environmental benefits. Seaweed would absorb carbon dioxide found in the sea and its “by-product” is oxygen that is required to sustain human life.

The most significant social threat to arise from seaweed farming is biosecurity risks. Fortunately, when compared to other countries, New Zealand is relatively free from aquatic pests and diseases.[28] Therefore the introduction of seaweed farming would not pose a risk of contaminating our water streams.[29]

3. Is all seaweed edible?

There were only 14 reported deaths related to eating seaweed in history and it was due to the bacteria grown on the seaweed that had caused these food-borne illnesses.[30]

That being said, it is still not advisable to go to the beach and try picking some “seaweed” for dinner since it’s hard to distinguish between seaweed and algae.

We hope you liked the article. If you have any questions on how to introduce seaweed to your daily or weekly meals, please let us know in the comments below. Also, for more articles on new food sources and emerging food technologies, please see our page The Future of Food.

Joyce is a dedicated and passionate undergraduate with a keen interest in research and development of novel foods. She is currently completing her studies with a focus on becoming a Bachelor of Food Technology with Honors major in Food Product Technology.

Her personal passion is in finding new technologies and processing methodologies that can improve the existing products in the food market.

Joyce is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest news here at D’Connect.

References

(1) Dayton, P. K. (1985). Ecology of kelp communities. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 16(1), 215-245.

(2) Marine Stewardship Council. Seaweed and microalgae. https://www.msc.org/what-you-can-do/eat-sustainable-seafood/fish-to-eat/seaweed

(3) Chung, I. K., Kang, Y. H., Charles, Y., George, P. K., & Lee, J. (2002). Application of seaweed cultivation to the bioremediation of nutrient-rich effluent. Algae, 17(3), 187-194. Mabeau, S., & Fleurence, J. (1993). Seaweed in food products: biochemical and nutritional aspects. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 4(4), 103-107.

(4) White, L. N., & White, W. L. (2020). Seaweed utilisation in New Zealand. Botanica Marina, 63(4), 303-313.

(5) Renn, D. (1997). Biotechnology and the red seaweed polysaccharide industry: status, needs and prospects. Trends in Biotechnology, 15(1), 9-14.

(6) Tabitha, N.(2020). Difference Between Algae and Seaweed.

(7) Samanthi (2021). Difference Between Seaweed and Seagrass. https://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-seaweed-and-seagrass/

(8) Ambrozova, J. V., Misurcova, L., Vicha, R., Machu, L., Samek, D., Baron, M., … & Jurikova, T. (2014). Influence of extractive solvents on lipid and fatty acids content of edible freshwater algal and seaweed products, the green microalga Chlorella kessleri and the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis. Molecules, 19(2), 2344-2360.

(9) Cheri, B. (2020). What’s the Difference Between Chlorella and Spirulina?

(10) Sharon,O. (2018). 7 Surprising Health Benefits of Eating Seaweed.

(11) Craig, R. (2018). Seaweed for Gut Health

(12) Aakre, I., Tveito Evensen, L., Kjellevold, M., Dahl, L., Henjum, S., Alexander, J., … & Markhus, M. W. (2020). Iodine status and thyroid function in a group of seaweed consumers in Norway. Nutrients, 12(11), 3483. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7697291/

(13) Pacific Harvest (2018). Seaweed for Detox – 5 Ways Seaweeds Uniquely Help to Cleanse!

(14) Natalie, B. (2018). What are the benefits of seaweed?

(15) Newcastle University. (2010). Seaweed to tackle rising tide of obesity. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/03/100321203508.htm

(16) Negishi, H., Mori, M., Mori, H., & Yamori, Y. (2013). Supplementation of elderly Japanese men and women with fucoidan from seaweed increases immune responses to seasonal influenza vaccination. The Journal of nutrition, 143(11), 1794-1798.

(17) Englund, J. A., Walter, E. B., Gbadebo, A., Monto, A. S., Zhu, Y., & Neuzil, K. M. (2006). Immunization with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in partially immunized toddlers. Pediatrics, 118(3), e579-e585.

(18) Nutr J. (2011). Seaweed intake and blood pressure levels in healthy pre-school Japanese children.

(19) Christina, L. (2011) Cooking to Control Pain: Seaweed

(20) Michikawa T, Inoue M, Shimazu T, Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, et al. (2012) Seaweed consumption and the risk of thyroid cancer in women: the Japan Public Health Centerbased Prospective Study. Eur J Cancer Prev.;21(3):254–60.

(21) Wang J, Yang H, Si Y, Hu D, Yu Y, Zhang Y, et al. (2017) Iodine promotes tumorigenesis of thyroid cancer by suppressing miR-422a and upregulating MAPK1. Cell Physiol Biochem;43(4):1325–36 https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/481844

(22) Küpper FC, Carpenter LJ, McFiggans GB, Palmer CJ, Waite TJ, Boneberg EM, et al. (2008). Iodide accumulation provides kelp with an inorganic antioxidant impacting atmospheric chemistry.

(23) Teas J, Pino S, Critchley A, Braverman LE. (2005). Variability of iodine content in common commercially available edible seaweeds.

(24) Chen, Q., Pan, X. D., Huang, B. F., & Han, J. L. (2018). Distribution of metals and metalloids in dried seaweeds and health risk to population in southeastern China. Scientific reports, 8(1), 1-7.

(25) Zava, T. T., & Zava, D. T. (2011). Assessment of Japanese iodine intake based on seaweed consumption in Japan: a literature-based analysis. Thyroid research, 4(1), 1-7.

(26) Leung, A. M., & Braverman, L. E. (2014). Consequences of excess iodine. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 10(3), 136-142. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3976240/

(27) Scoones, I. (2007). Sustainability. Development in practice, 17(4-5), 589-596.

(28) Goldson, S. L., Bourdôt, G. W., Brockerhoff, E. G., Byrom, A. E., Clout, M. N., McGlone, M. S., … & Templeton, M. D. (2015). New Zealand pest management: current and future challenges. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 45(1), 31-58.

(29) Ministry for Primary Industries.

(30) Cheney, D. (2016). Toxic and harmful seaweeds. In Seaweed in health and disease prevention (pp. 407-421). Academic Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300409677_Toxic_and_Harmful_Seaweeds