Elisa Weiss

RNutr, BSc Human Nutrition (Argentina)

While the precise details of Sardinia’s exceptional longevity remain unclear, we will delve into the scientific foundations that involve the intricate interplay of:

- genetic factors

- lifestyle choices

- community dynamics

that collectively contribute to the island’s remarkable health outcomes.

The Blue Zones — Sardinia

The Blue Zones, regions renowned for defying the conventional expectations of ageing by fostering longevity and well-being, have become a subject of widespread fascination for researchers and health enthusiasts globally.

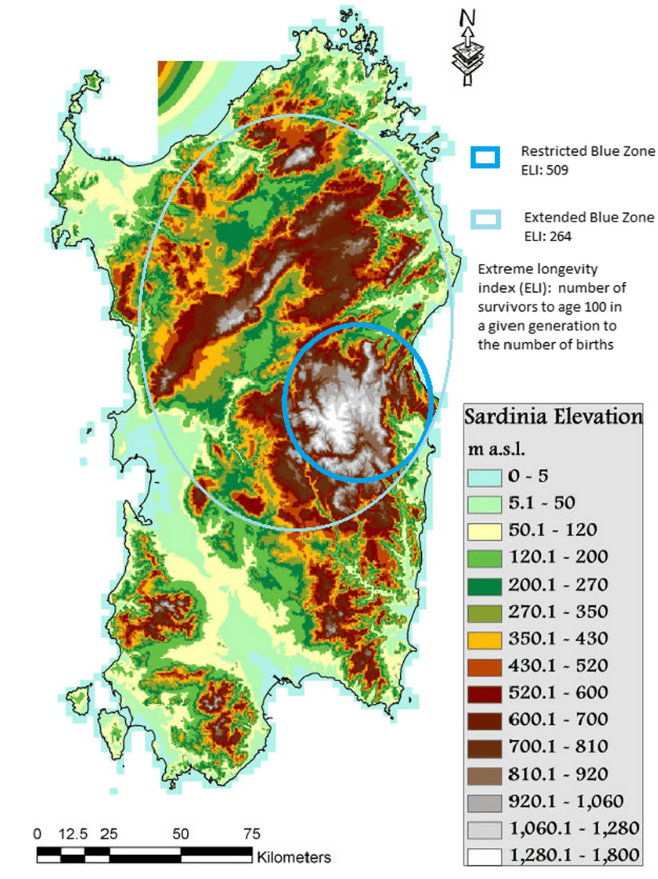

Among these enigmatic zones, Sardinia, a secluded mountainous area in Italy, the second-largest Mediterranean island, stands as a remarkable hub of centenarians and a population that experiences extended and healthy lives.[1,2]

Source: Slowfood.com

Characterised by its traditional lifestyle, predominantly centred around raising livestock and agricultural activities, the inhabitants of Sardinia lead a simple life dedicated to preserving local traditions.

Genetics

Population longevity is observed when a more significant proportion of individuals survive to the oldest ages in a particular population, surpassing a predetermined threshold deviation from its neighbouring areas.[3]

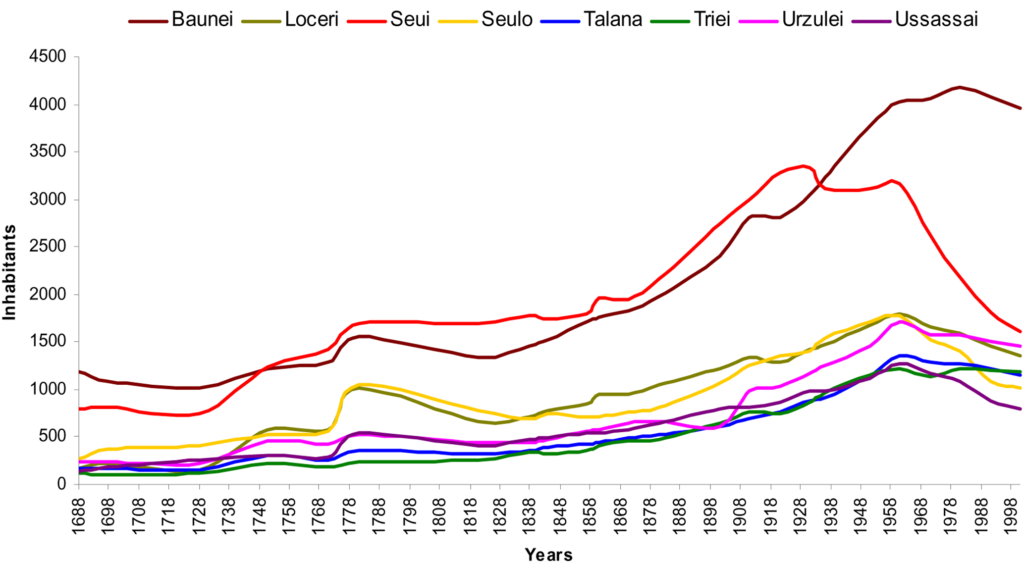

The extraordinary prevalence of centenarians in Sardinia distinguishes it from other populations.[4] Despite the common trend of women outliving men, what sets Sardinia apart is that centenarian men share a similar life expectancy with women, contrasting to other regions in Italy.[5]

In Sardinia, centenarian men share a similar life expectancy as women

Sardinia’s distinctive genetic landscape underlines a hereditary element that contributes to the region’s Blue Zone status, exhibiting longevity advantages in both demographic and health aspects compared to the rest of Italy and Greece[6] The genetic blueprint is marked by the following specifics.

Genetic Isolation

Sardinia’s relative isolation from mainland Italy and other European regions has led to a unique genetic profile. The population has experienced limited gene flow from outside regions, contributing to genetic homogeneity.[7]

Intra-Island Genetic Diversity

Despite the overall genetic homogeneity, Sardinian populations still display genetic diversity within the island. Different regions’ specific genetic markers reflect historical interactions and migrations.[8,9]

Candidate Genes

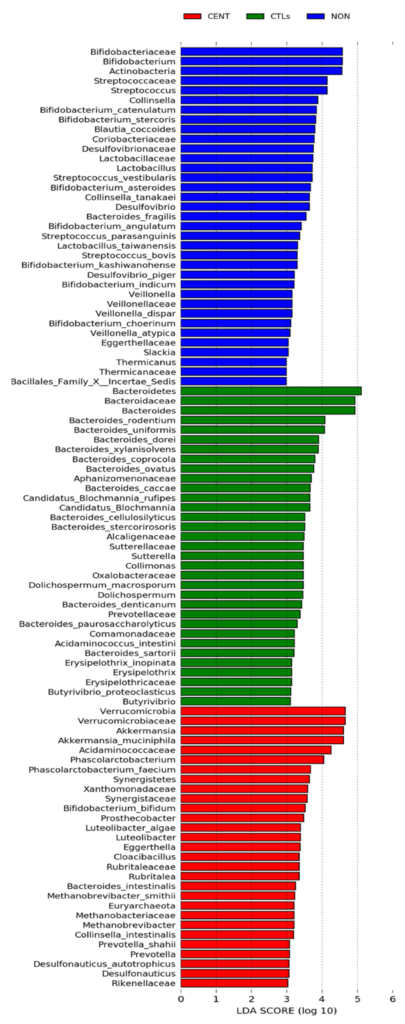

Researchers have investigated candidate genes associated with ageing and longevity in Sardinia.[10] Studies on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), gut microbiota markers and specific genetic variations provide insights into potential factors influencing lifespan but are still far from explaining their longevity.[11,12,13]

Although genetics are considered less critical than behavioural and health indicators, more research is still needed to identify possible epigenetic traits.

Epigenetic traits could play a predominant role due to the interaction between genetics and the human and physical environments.[14,15]

Social and Community Dynamics: Influential Aspects of Lifestyle

While genetics lay a foundation, lifestyle factors are pivotal in Sardinia’s longevity narrative.

For instance, research indicates that a higher percentage of the oldest individuals in the Sardinian Longevity Blue Zones (LBZ) are still married or maintain close relationships with family members or partners.

Typically, most older people live with their family members throughout their lives, which can potentially aid in managing age-related illnesses more effectively than those in institutionalised settings.[16,17]

Traditional Sardinian families often prioritise collectivist values in their living conditions. This social connectivity appears to contribute to their overall well-being.[18]

However, while it suggests that family networks may contribute to the mental health of Sardinian adults, there is a lack of direct empirical support for this notion.[19]

Additionally, they exhibit elevated self-rated health and optimism scores. Despite the presence of adverse conditions including a higher prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) and a historical trend in smoking, although the latter shows a decreasing pattern.[20,21]

In the Blue Zone of Sardinia, people lead a simple life, and a large proportion of shepherds still preserve their cultural traditions and resist change.[22]

Psychosocial research on successful ageing in Sardinia indicates that mentally sound older individuals experience better-preserved mental health compared to counterparts in northern Italy’s rural areas.

The collectivist culture in Sardinia, where older people are valuable resources, is considered a protective factor for ageing well.[23,24,25]

Sardinia has a strong sense of community and social connections

Active participation in the community, adherence to local traditions, and autonomy among older individuals contribute significantly to maintaining high levels of mental health.[26]

Religion as a factor in longevity

Ethnographic research reveals that religious practices in Sardinia, carried out mainly by older Catholic women, strengthen social identity through collective historical representations and local rituals.

Current studies have not explored the impact of religiosity on successful ageing in the Blue Zone.

However, a study with older participants from Sardinia found moderate, positive relationships between religiosity and perceived psychological well-being in late adulthood.[27]

Sardinian diet

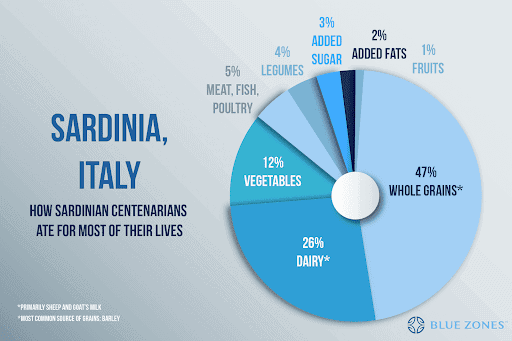

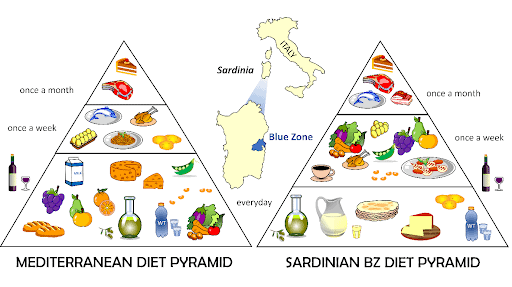

The traditional Sardo-Mediterranean diet places a strong emphasis on plant-based foods, including whole grains (wheat, barley and more rarely corn), fruits, vegetables, and legumes.[5,28,29]

This distinctive dietary pattern is characterised by significantly higher vegetable consumption, constituting 12% of total calories, compared to the 6%, 2.5%, and 1.3% found in the average person in France, the rest of Italy, and the Czech Republic, respectively.

Olive oil, a dietary cornerstone, contributes antioxidants and healthy fats, promoting general well-being.[30,31]

Daily consumption of nuts, such as almonds (rich in vitamin E and magnesium), pistachios, and walnuts (rich in alpha-linolenic acid and omega-3 fats), is a common practice.[31]

RELATED — Magnesium (for a great night of sleep)

Their diet minimises meat intake (5% compared to 10-16% in European or American countries), often as a celebratory or flavouring element. It is worth mentioning that the meat came from locally raised animals, and items such as cured meat, ham, sausages and salami were made in-house.

As a result, this processed meat is composed only of salt and spices, such as pepper and garlic, without preservatives or chemical additives and are consumed modestly 3 to 5 times weekly.

RELATED — 5 Most Common Food Additives in our Food (and should we avoid them)?

On the other hand, inhabitants of Sardinia rely on dairy products, usually typical homemade products, particularly goat and sheep cheese varieties like ricotta (whey cheese, dried curd), pecorino (aged cheese), and casu ajedu (fresh sour cheese, which is rich in Lactobacilli).[5,31]

Source: Thecheeseatlas.com

In contrast to the Standard American Diet, where 47.3% is derived from carbohydrates and only 13.7% of grain intake is whole grains, the traditional Sardinian diet derives 47% of its calories from whole grains.[5]

In this food group, derivatives are made with them, such as homemade pasta and the iconic Pane carasau, a sourdough flatbread made with durum wheat flour, yeast, water, and salt.

Studies show that the lactic acid bacteria in its sourdough create peptides and γ-aminobutyric acid, offering potential antihypertensive effects.[5,32,33]

Source: Palmas, V. Gut Microbiota Markers and Dietary Habits Associated with Extreme Longevity in Healthy Sardinian Centenarians. (2022)

Additionally, Pane carasau has a low glycemic index, helping to lower the risk of chronic diseases, including diabetes.

RELATED — Diabetes: Early Signs, Causes, Types and Treatment

Notably, the Sardinian diet restricts added sugar to just 3% of total calories, a stark contrast to the nearly 23% seen in the Standard American Diet. Although sweets are rarely consumed, Sardinians exhibit a high daily intake of coffee.

Studies suggest long-term, dose-dependent benefits associated with coffee consumption, such as a reduced risk of:

- Type 2 diabetes

- Parkinson’s disease

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Alcoholic cirrhosis

- Gout[34,35,36]

Additionally, several studies have suggested a mild inverse relationship between coffee consumption and overall mortality.[36]

A distinctive feature, though subject to scrutiny in some ecological studies regarding its impact on life expectancy, is the practice of moderate alcohol consumption.[37] This is often associated with the daily intake of Cannonau red wine, renowned for its high polyphenol content.[15,28,30]

The Longevity Blue Zone (LBZ) generations born in the late 19th century experienced more extended exposure to the traditional diet, maintaining this lifestyle for an extended period.

Notably, changes emerged, such as heightened consumption of vegetables, olive oil, and meat (particularly chicken) and reduced milk intake.[37] An increase in soft cheeses, cottage cheese, and yoghurt compensated for this decrease.[31]

The heart of Sardinian dietary practices revolves around the pivotal role of housewives, dedicating time to culinary pursuits. Meal preparation is characterised by incorporating herbs and spices, with lunch as the principal dish.[29]

RELATED — Anti-cancer foods: The Healthiest Herbs and Spices (Part 1)

Data from Sardinia in 2001 reveal distinct meal structures, with children often having morning snacks, unlike adults. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner are significant family gatherings, reflecting the enduring Sardo-Mediterranean culinary traditions prioritising quality over quantity.

Emphasising locally sourced foods and traditional cooking aligns with the Mediterranean-style diet, reducing risks of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer.[38]

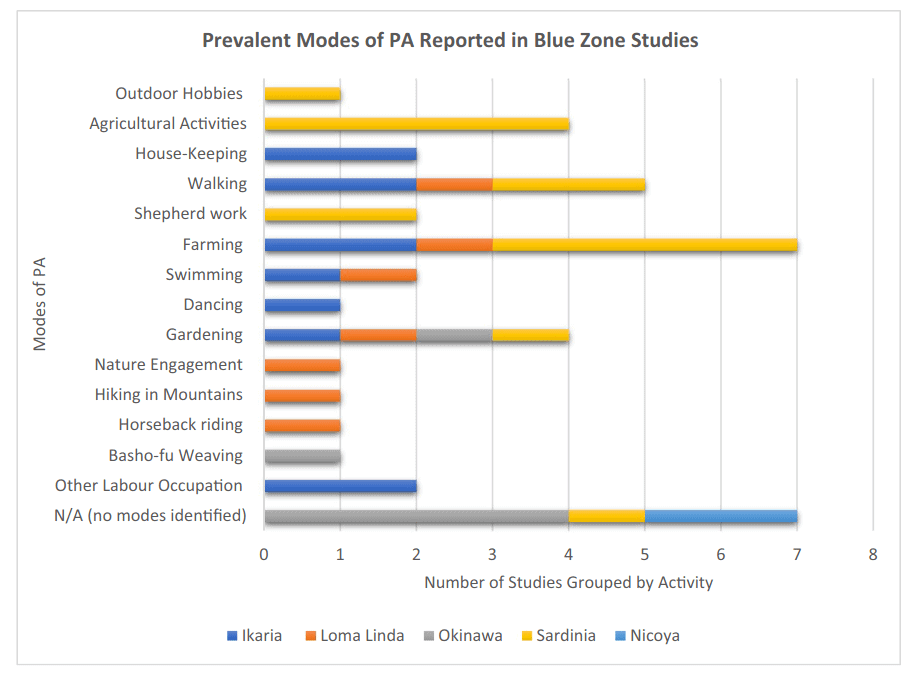

Physical Activity

The active lifestyle of Sardinians, closely intertwined with the island’s rugged landscapes and hilly terrain, is a crucial factor contributing to their longevity.

A scoping review conducted in 2022 emphasised the prevalence of shepherding as the primary occupation in Sardinia’s Blue Zone region.

Shepherds cover an average daily walking distance of approximately 12.4 ± 7.8 km, navigating through an average slope of 15.2 ± 6.6%.[39,40]

This physically demanding occupation is consistently maintained at a moderate intensity throughout the year, involving the traversal of steep and narrow paths that mirror the challenging terrain of the mountainous regions.[39]

Additional walking-related parameters included Sardinians aged 90 years or older taking an average of 12,110 steps per day for men and 12,799 for women, regardless of specific activity.[40]

Regarding agricultural activities, most Sardinians aged 90 years or older reported participating in gardening activities between 1 and 4 days per week, dedicating an average of 1.7 to 2.3 hours per week to outdoor hobbies.

Sardinians walk on average over 12,000 steps per day

Daily activities, from tending to fields to engaging in traditional dances, seamlessly integrate physical activity into the Sardinian way of life.[24]

Studies in this population showed that perceived physical health, time spent gardening, and engagement in physical activities were negatively correlated with depressive symptoms.[41,42]

Although limited in data, recent studies indicate that the average sleep duration is adequate even among centenarians. Among men, it is approximately 5.9 hours; among women, it is 5.6 hours, with 57% of nonagenarians reporting 6-7 hours of daily sleep.[40]

A different measurement approach for Sardinian participants aged 90 and above showed similar results in terms of productive rest.

The total daily rest time, calculated based on nightly sleep duration and time spent supine during the waking day, averaged 8.5 hours for men and 7.4 hours for women over a 24-hour period.[40,41]

Lessons from Sardinia's Longevity

While understanding the secrets of Sardinia’s Blue Zone does not mean that it is a dietary pattern that the entire population must follow, it provides crucial information about the critical components of a long and healthy life.

This distinctive region interweaves unique genetic factors with a wellness-focused lifestyle. The Sardo-Mediterranean diet of the islanders, rich in whole and fermented foods, emphasises the importance of homemade, locally sourced and seasonal products, with no room for ultra-processed products.

Beyond mere nutrition, this dietary philosophy shapes a holistic way of life, fostering strong community bonds and an active lifestyle.

Equally noteworthy is the generous rest that centenarians enjoy, highlighting the profound link between physical and mental well-being and a notable reduction in stress levels.

These elements thrive on the support and understanding of the surrounding community, offering a roadmap for modern strategies to promote healthy ageing.

Related Questions

1. What does a typical Sardinian breakfast look like?

A typical Sardinian breakfast is characterised by simplicity and wholesomeness, often featuring options such as whole-grain bread or traditional Sardinian flatbread, such as Pane carasau, which might be accompanied by local goat or sheep cheese, homemade jams or honey.

Complementing this, you might find locally sourced fruits, such as oranges or figs, and a small cup of espresso.[43]

2. What vegetables and grains do they prefer in Sardinia?

Sardinians prefer a variety of locally grown and seasonal vegetables, including staples such as:

- artichokes

- tomatoes

- eggplant

- fennel[5,31]

A traditional meal with these ingredients is vegetable soup (minestrone) that contains garden veggies (onions, fennel, carrots, celery).

Cereals are essential in their diet, highlighting whole grains such as durum wheat, barley and semolina, commonly found in traditional Sardinian bread and pasta.[43]

3. What type of meat is preferred in Sardinia?

While Sardinians consume meat in modest amounts, their preference leans towards lean and high-quality options.

Meat is commonly prepared in stews or roasted dishes featuring beef, pork, goat meat, lamb, and poultry. In coastal areas, the diet may also include fish and shellfish.[15,28,30,37]

If you are interested in the Blue Zone diet, or have any questions regarding the article, please let us know in the comments below.

Elisa Weiss is a New Zealand Registered Nutritionist specialising in obesity, type 2 diabetes and digestive disorders. She has worked in community settings and private practice, focusing on holistic approaches to improve people’s health and well-being.

Elisa has a background in research, education and food science. Elisa is certified as a Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) practitioner and has completed undergraduate and graduate studies in nutrition and dietetics, diabetes management and Ayurvedic medicine. She is currently doing a postgraduate diploma in Biomedical Sciences. She works in private practice using a no-diet and evidence-based approach.

Elisa is also actively involved in volunteer and professional development activities. You will find her doing outdoor activities or experimenting in the kitchen with different ferments when she is not working or studying.

References

(1) Poulain M, Herm A. (2021) Blue Zone : A model to live longer and better. Positive Ageing and Learning from Centenarians.

(2) Kreouzi M, Theodorakis N, Constantinou C. (2022) Lessons Learned From Blue Zones, Lifestyle Medicine Pillars and Beyond: An Update on the Contributions of Behavior and Genetics to Wellbeing and Longevity. Am J Lifestyle Med. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/15598276221118494

(3) Poulain M. (2019) Individual Longevity Versus Population Longevity. Centenarians: An Example of Positive Biology.

(4) Nieddu A. (1999) AKEntAnnos. The Sardinia Study of Extreme Longevity. Ageing Clin Exp Res.

(5) Wang C, Murgia MA, Baptista J, Marcone MF. (2022) Sardinian dietary analysis for longevity: a review of the literature. Journal of Ethnic Foods. https://journalofethnicfoods.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s42779-022-00152-5

(6) Poulain M, Herm A, Errigo A, Chrysohoou C, Legrand R, Passarino G, et al.(2021) Specific features of the oldest old from the Longevity Blue Zones in Ikaria and Sardinia. Mech Ageing.

(7) Chiang CWK, Marcus JH, Sidore C, Biddanda A, Al-Asadi H, Zoledziewska M, et al. (2018) Genomic history of the Sardinian population. Nat Genet.

(8) Pistis G, Piras I, Pirastu N, Persico I, Sassu A, Picciau A, et al. (2009) High Differentiation among Eight Villages in a Secluded Area of Sardinia Revealed by Genome-Wide High Density SNPs Analysis. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0004654

(9) Robledo R, Vona G, Sanna E, Bachis V, Calò CM. (2018) Analysis of uniparental markers reveals a complex pattern of migration within Sardinia. Ann Hum Biol.

(10) Chung WH, Dao RL, Chen LK, Hung SI. (2010) The role of genetic variants in human longevity. Ageing Res Rev.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1568163710000589?via%3Dihub

(11) Passarino G, Underhill PA, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Semino O, Pes GM, Carru C, et al. (2001) Y Chromosome Binary Markers to Study the High Prevalence of Males in Sardinian Centenarians and the Genetic Structure of the Sardinian Population. Hum Hered.

(12) Pes GM, Lio D, Carru C, Deiana L, Baggio G, Franceschi C, et al. (2004) Association between longevity and cytokine gene polymorphisms. A study in Sardinian centenarians. Ageing Clin Exp.

(13) Palmas V, Pisanu S, Madau V, Casula E, Deledda A, Cusano R, et al. (2023) Gut Microbiota Markers and Dietary Habits Associated with Extreme Longevity in Healthy Sardinian Centenarians. Nutrients. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/14/12/2436

(14) Floris P, Dore MP, Pes GM. (2021) Does the longevity of the Sardinian population date back to Roman times? A comprehensive review of the available evidence. PLoS One. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0245006

(15) Nieddu A, Vindas L, Errigo A, Vindas J, Pes GM, Dore MP.(2020) Dietary Habits, Anthropometric Features and Daily Performance in Two Independent Long-Lived Populations from Nicoya peninsula (Costa Rica) and Ogliastra (Sardinia). Nutrients.

(16) Hitchcott PK, Fastame MC, Ferrai J, Penna MP. (2017) Psychological Well-Being in Italian Families: An Exploratory Approach to the Study of Mental Health Across the Adult Life Span in the Blue Zone. Eur J Psychol.

(17) Fastame MC, Penna MP, Rossetti ES, Agus M. (2014) The Effect of Age and Socio-Cultural Factors on Self-Rated Well-Being and Metacognitive and Mnestic Efficiency Among Healthy Elderly People. Appl Res Qual Life.

(18) Fastame MC, Hitchcott PK, Mulas I, Ruiu M, Penna MP. (2018) Resilience in Elders of the Sardinian Blue Zone: An Explorative Study. Behavioral Sciences. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/8/3/30

(19) Fastame MC, Penna MP. (2014) Psychological well-being and metacognition in the fourth age: an explorative study in an Italian oldest old sample. Ageing Ment Health.

(20) Roundtable on Population Health Improvement; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Institute of Medicine. Business Engagement in Building Healthy Communities: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015 May 8. 2, Lessons from the Blue Zones.

(21) Muntoni S, Atzori L, Mereu R, Manca A, Satta G, Gentilini A, et al. (2009) Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Sardinia from 1978 to 2001: A comparative study with Italian mainland. Eur J Intern Med.

(22) Fastame MC, Ruiu M, Mulas I. (2021) Mental Health and Religiosity in the Sardinian Blue Zone: Life Satisfaction and Optimism for Ageing Well. J Relig Health. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10943-021-01261-2

(23) Fastame MC, Penna MP, Rossetti ES. (2014) Perceived Cognitive Efficiency and Subjective Well-Being in Late Adulthood: The Impact of Developmental Factors. J Adult Dev.

(24) Fastame MC, Hitchcott PK, Penna MP. (2018) The impact of leisure on mental health of Sardinian elderly from the ‘blue zone’: evidence for ageing well. Ageing Clin Exp Res.

(25) Fastame MC, Hitchcott PK, Mulas I, Ruiu M, Penna MP. (2018) Resilience in Elders of the Sardinian Blue Zone: An Explorative Study. Behavioral Sciences. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5867483/

(26) Teo RH, Cheng WH, Cheng LJ, Lau Y, Lau ST. (2023) Global prevalence of social isolation among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr.

(27) Ji, LJ., Imtiaz, F., Su, Y. et al. Culture, Ageing, Self-Continuity, and Life Satisfaction. J Happiness Stud 23, 3843–3864 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00568-5

(28) Buettner D, Skemp S. (2016) Blue Zones: Lessons From the World’s Longest Lived. Am J Lifestyle Med.

(29) Tessier S, Gerber M. (2005) Comparison between Sardinia and Malta: The Mediterranean diet revisited. Appetite.

(30) Sardinia, Italy – Blue Zones

(31) Pes GM, Tolu F, Dore MP, Sechi GP, Errigo A, Canelada A, et al. (2014) Male longevity in Sardinia, a review of historical sources supporting a causal link with dietary factors. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015.

(32) Verni M, Vekka A, Immonen M, Katina K, Rizzello CG, Coda R. (2022) Biosynthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid by lactic acid bacteria in surplus bread and its use in bread making. J Appl Microbiol. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9544796/

(33) Devi PB, Rajapuram DR, Jayamanohar J, Verma M, Kavitake D, Meenachi Avany BA, et al. (2023) Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production by potential probiotic strains of indigenous fermented foods origin and RSM based production optimisation. LWT. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0023643823000890?via%3Dihub

(34) Kim Y, Je Y, Giovannucci E. (2019) Coffee consumption and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a meta-analysis by potential modifiers. Eur J Epidemiol.

(35) Nieber K. (2017) The Impact of Coffee on Health. Planta Med.

(36) Siasos G, Oikonomou E, Chrysohoou C, Tousoulis D, Panagiotakos D, Zaromitidou M, et al. (2013) Consumption of a boiled Greek type of coffee is associated with improved endothelial function: The Ikaria Study. Vascular Medicine (United Kingdom). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1358863X13480258

(37) Pes GM, Poulain M, Errigo A, Dore MP. (2021) Evolution of the dietary patterns across nutrition transition in the Sardinian longevity blue zone and association with health indicators in the oldest old. Nutrients. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/5/1495

(38) Gerber M, Hoffman R. (2015) The Mediterranean diet: health, science and society. British Journal of Nutrition. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/mediterranean-diet-health-science-and-society/2AD00DAC00E6C5AA6139F81A9D12A37C

(39) Pes GM, Tolu F, Poulain M, Errigo A, Masala S, Pietrobelli A, et al. (2013) Lifestyle and nutrition related to male longevity in Sardinia: An ecological study. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases.

(40) Pes GM, Dore MP, Errigo A, Poulain M. (2018) Analysis of Physical Activity Among Free–Living Nonagenarians From a Sardinian Longevous Population. J Ageing Phys Act. https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/japa/26/2/article-p254.xml

(41) Herbert C, House M, Dietzman R, Climstein M, Furness J, Kemp-Smith K. (2022) Blue Zones: Centenarian Modes of Physical Activity: A Scoping Review. J Popul Ageing. https://pure.bond.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/200782461/Blue_Zones.pdf

(42) Fastame MC. (2022) Well-being, food habits, and lifestyle for longevity. Preliminary evidence from the Sardinian centenarians and long-lived people of the Blue Zone. Psychol Health Med.

(43) Pes GM, Dore MP, Tsofliou F, Poulain M. (2022) Diet and longevity in the Blue Zones: A set-and-forget issue? Maturitas