Anishka Ram

(NZRD, MSc. Nutrition and Dietetics)

Hepatitis is a medical inflammatory condition which happens when a virus affects the liver, which can lead to long term liver damage. The most common types are Hepatitis A, B, C, D and E.

Hepatitis infection symptoms can range from fatigue, loss of appetite, dark urine, joint pains and others, while some can show no symptoms at all. Hepatitis infections are commonly spread by poor hygiene, contaminated food and water, bodily fluids and needles.

Hepatitis is a widespread condition and today we will have a special focus on New Zealand and our population regarding hepatitis infections and statistics.

What is Hepatitis?

Hepatitis is a condition when a virus causes inflammation of the liver. Inflammation eventually leads to scarring of the liver tissue, also known as fibrosis and can result in poor function, leading to liver disease and cancer.[1]

The function of the liver

The role of the liver is to filter the blood in our body. It receives the blood from our digestive tract and then filters the blood and nutrients.

Once this is completed, the liver then sends the filtered blood and metabolized nutrients to the rest of the body.[2]

Liver is an essential organ for filtering toxins out of our bloodstream and our body.

What are the 5 types of Hepatitis (with symptoms)

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is commonly contracted in food service environments and daycare centers as a result of poor hygiene practices (e.g. contamination of food by feces).[3]

In developed countries, Hepatitis A infections can be characterized by jaundice and acute hepatitis, especially in adolescents and adults.

In other parts of the world, Hepatitis A outbreaks have been or are linked to contamination of water, poor sanitation, homelessness, overcrowding and injection drug use.[3,4] Shellfish have also been the cause of past large epidemics due the contamination of sea water with waste water.[4]

Hepatitis A symptoms are nausea, vomiting and jaundice.[5] Luckily, Hepatitis A is not common in New Zealand.

However, if you are travelling make sure to let your GP know, who will then recommend vaccines to take before your trip to countries where Hepatitis A is more common.

Hepatitis A vaccine is available commercially. There are 2 types of Hepatitis A vaccine which are Havrix and Havrix Junior for adults and children respectively.[3]

The vaccine is funded (in NZ) for people at very high risk for Hepatitis A, including people with liver transplant, those living close to people with the Hepatitis A infection and children with chronic liver disease.[3]

Hepatitis B

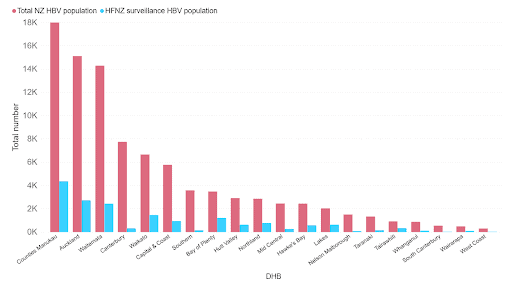

There are about 100,000 Kiwis with Hepatitis B. However, it is expected that there are more infected with Hepatitis B without knowing it. Hepatitis B is a type of virus that is passed from one person to another through bodily fluids, leading to an acute infection of the liver.[6]

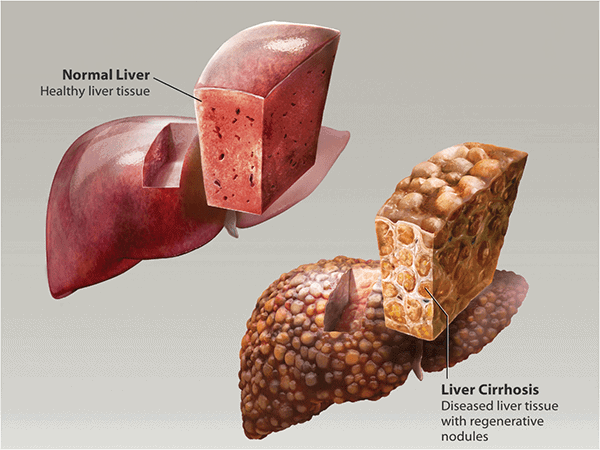

Symptoms include joint and abdominal pain, fatigue and fever. Although Hepatitis B is a short-term infection and people can make a quick recovery, it is important to know if you have contracted Hepatitis B, the virus will continue circulating in the blood and around the liver. This will cause serious long term problems such as chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and liver cancer.[7]

The good news is that Hep B is less likely to be found in New Zealander’s 25 years and under.[7] Although Hepatitis B is common, children are given the vaccine for Hepatitis B at 6 weeks, 3 months and 5 months of age as part of their free immunisations.

Before the vaccine, Hepatitis B was common in NZ in the 1980’s.[6]

Hepatitis C

With Hepatitis C, the infection spreads by being in contact with another person’s blood. In New Zealand, the common risk factor of being infected by Hepatitis C is by unsterilized needles and syringes, meaning tattoo needles and body piercing equipment.[8]

This also includes injecting drugs, which is common among people who share their needles.[9]

Hepatitis C travels to the liver causing inflammation but symptoms may not appear (asymptomatic) for years due to Hepatitis C being undetected through lab tests. As Hepatitis C infection leads to long term liver damage, it is the primary reason for people to be considered for liver transplant in New Zealand.[8]

The symptoms usually associated with Hepatitis C may be mistaken for another illness as it includes bleeding and bruising easily, fever, feeling tired, low or no appetite, joint pain, upset stomach and vomiting, jaundice and dark urine.[9,10]

Over 50% of people thought to have Hepatitis C are undiagnosed with no knowledge of the effects on their liver, while 25% of people can develop cirrhosis. This is one of the reasons why it is important to have a Hepatitis Awareness Day.[8,9,11]

Other types of hepatitis

Hepatitis D is the rarest type of Hepatitis, however, it is the most severe form of infection that can damage the liver faster than all other forms of hepatitis.[13]

There is no vaccine for Hepatitis D, with the best method being to avoid contracting Hepatitis D altogether. Hepatitis D can be contracted through exchange of blood from one person to another.[14]

Hepatitis E is the most common form of acute hepatitis and can be asymptomatic. It spreads through ingestion of the virus, meaning water or food.

The infection can be resolved within weeks, however, acute liver failure (fulminant hepatitis) can occur, which can lead to death.[15]

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis causes inflammation of the liver over a long period of time and can lead to permanent scarring and damage to the liver. This type of hepatitis can affect anyone, however it is mostly presented in women.

This type of hepatitis can affect anyone, however it is mostly presented in women. Autoimmune hepatitis requires people to take steroid based medications.[16]

How to avoid being infected

There are several risk groups regarding higher rates of infection with hepatitis and we must be aware of them to avoid any and all infections with the hepatitis virus.

Population group

There are regions worldwide where Hepatitis B is an epidemic which include Asia, Pacific Islands, Africa (and Northern or Eastern parts of New Zealand’s North Island).[17]

Bodily fluids and STD

Contact or mixing of bodily fluids, including dried blood, can lead to contracting hepatitis. This is because blood can circulate with the virus around the body and seep into other bodily fluids which can be passed on to others. Another way hepatitis can be commonly contracted is through sexual contact with a person who already has the hepatitis virus.[7]

Unsterilised needles

Syringe needles and tattoo needles that are used on multiple people can lead to contracting the hepatitis virus as one person’s bodily fluid can enter the bloodstream of another person, causing infection.[7]

Pregnancy

The end stage of pregnancy is when there is a high risk for mothers to pass Hepatitis B onto their baby. It is important to keep the mother safe and make sure the pregnancy is monitored. Unfortunately, when a newborn or child contracts Hepatitis B they can have a lifelong infection, sometimes not showing any symptoms.[7]

Conclusion

Hepatitis in New Zealand – There are around 150,000 people in New Zealand with Hepatitis B (100,000) and Hepatitis C (50,000).

Hepatitis Worldwide – Close to 300 million people in the world have Hepatitis B, while 59 million people are living with Hepatitis C. Worldwide prevalence of hepatitis are in regions such as Asia, Africa, South America and the Middle East.

Can hepatitis be cured – While the body can clear itself from the virus (depending on the type), there is no cure for the hepatitis virus. However, vaccinations are available for Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B viruses.

At the moment, there is no vaccine for Hepatitis C, but the researchers are testing different types of possible vaccines on chronic hepatitis C cases.

References

(1) Hepatitis C Trust. (2021). How Hepatitis C damages the liver.

(2) Trefts, E., Gannon, M., & Wasserman, D. H. (2017). The liver. Current biology : CB, 27(21), R1147–R1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.019.

(3) Health Navigator. (2021). Hepatitis A vaccine. https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/medicines/h/hepatitis-a-vaccine/

(4) Fusco, G., Anastasio, A., Kingsley, D. H., Amoroso, M. G., Pepe, T., Fratamico, P. M., Cioffi, B., Rossi, R., La Rosa, G., & Boccia, F. (2019). Detection of Hepatitis A Virus and Other Enteric Viruses in Shellfish Collected in the Gulf of Naples, Italy. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(14), 2588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142588.

(5) Thuener J. (2017). Hepatitis A and B Infections. Primary care, 44(4), 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2017.07.005

(6) Ministry of Health. (2020). Hepatitis B.

(7) The Hepatitis Foundation of New Zealand. (Date Unknown). Hepatitis.

(8) Ministry of Health. (2021). Hepatitis C.

(9) Millman, A. J., Nelson, N. P., & Vellozzi, C. (2017). Hepatitis C: Review of the Epidemiology, Clinical Care, and Continued Challenges in the Direct Acting Antiviral Era. Current epidemiology reports, 4(2), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-017-0108-x.

(10) Health Navigator. (2019). Hepatitis C (Pokenga Huaketo).

(11) Grgurevic, I., Bozin, T., & Madir, A. (2017). Hepatitis C is now curable, but what happens with cirrhosis and portal hypertension afterwards?. Clinical and experimental hepatology, 3(4), 181–186. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321336935_Hepatitis_C_is_now_curable_but_what_happens_with_cirrhosis_and_portal_hypertension_afterwards

(12) Best Practice Advocacy Centre (BPAC). (2019). Hepatitis C management in primary care has changed.

(13) Da, B. L., Heller, T., & Koh, C. (2019). Hepatitis D infection: from initial discovery to current investigational therapies. Gastroenterology report, 7(4), 231–245. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334820587_Hepatitis_D_infection_From_initial_discovery_to_current_investigational_therapies

(14) The Hepatitis Foundation of New Zealand. (n.d.). Hepatitis D.

(15) Lhomme, S., Marion, O., Abravanel, F., Izopet, J., & Kamar, N. (2020). Clinical Manifestations, Pathogenesis and Treatment of Hepatitis E Virus Infections. Journal of clinical medicine, 9(2), 331. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338811854_Clinical_Manifestations_Pathogenesis_and_Treatment_of_Hepatitis_E_Virus_Infections

(16) Pape, S., Schramm, C., & Gevers, T. J. (2019). Clinical management of autoimmune hepatitis. United European gastroenterology journal, 7(9), 1156–1163. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050640619872408

(17) The Hepatitis Foundation of New Zealand. (2019). Hepatitis B for health professionals.