Joyce Roberts

BHSc Nsg, Post Grad Cert Adv Nsg, Post Grad Dip Adv Nsg, Accredited Diabetes Nurse Specialist

For a person who has type 1 diabetes ongoing education and review of their diabetes management is important concerning the quality of their life and also their lifespan.

This is why it’s important to know more about:

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

- Ketosis

- Kussmaul Respiration

- Dehydration

- Gastrointestinal symptoms

- Hypoglycemia

since all of these conditions can occur due to fluctuations in blood glucose levels.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) is one of the acute complications of type 1 diabetes and is a life-threatening medical emergency requiring urgent medical attention.

DKA occurs due to insulin deficiency, either absolute or relative. Absolute insulin deficiency is related mostly to the new diagnosis of type 1 diabetes or omission of insulin while relative insulin deficiency is related to increased counter-regulatory hormones.[1]

DKA is more common in type 1 diabetes

In a state of insulin deficiency there is an increase in insulin counter regulatory hormones including:

- catecholamines

- cortisol

- glucagon

- growth hormone

These hormones antagonise insulin by increasing glucose production as well as decreasing the use of glucose.

The most common reason for DKA is either first presentation of the disease or an accompanying illness such as an:

- infection

- trauma

- surgery

- cardiac event

Other factors include interruption of insulin administration, either deliberate or accidental or insulin pump failure.

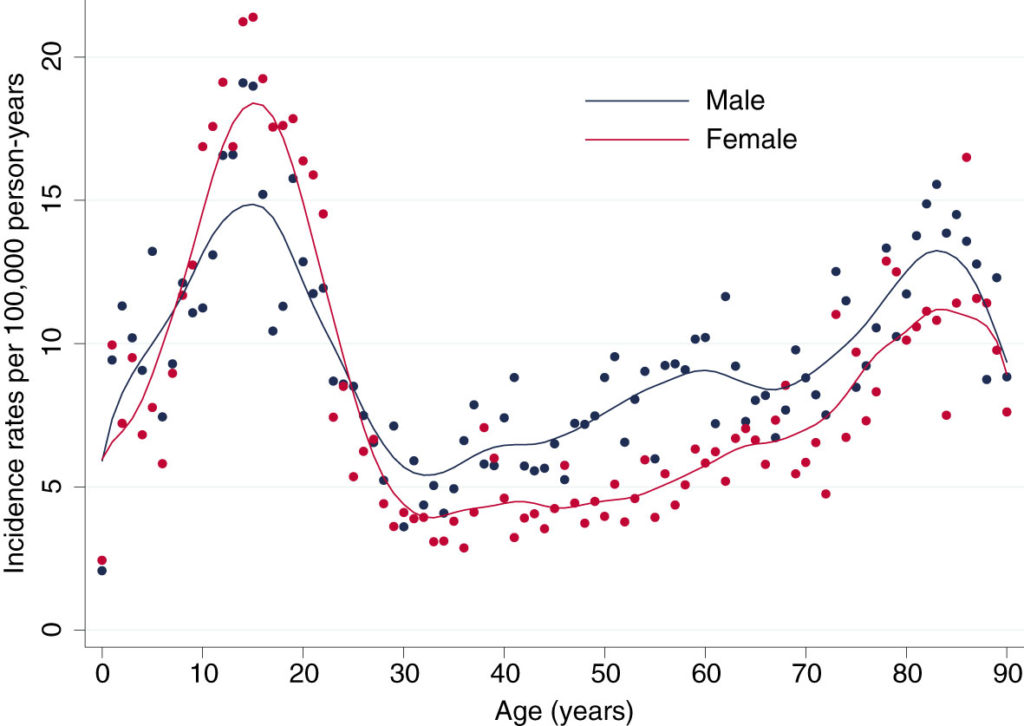

Source: Kutz, A. Lifetime risk and health-care burden of diabetic ketoacidosis: A population-based study. (2022)

The cause of DKA involves reduction of the effective insulin concentrations in the body, which are not able to match the glycemic overload either due to high intake or increased concentrations of counter-regulatory hormones. This imbalance leads to:

- hyperglycemia

- dehydration

- ketosis

- electrolyte imbalance[2]

The onset of DKA is slow

Signs and symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis include:

- Kussmaul respirations (hyperventilation in an attempt to compensate for the acidosis)

- postural dizziness

- central nervous system depression

- ketonuria (high levels of ketones present in the urine )

- anorexia

- nausea

- abdominal pain

- thirst

- polyuria

These symptoms of DKA are caused by hyperglycemia.

Ketosis

Ketosis is a metabolic state in which the body uses fat and ketones instead of glucose as the main fuel source.

Ketone bodies are produced by the oxidation of fatty acids in the liver as a source of alternative energy that generally occurs when glucose levels are low.[3]

When the concentration of ketones reaches above the normal levels acidosis ensues. Acidosis is a condition where the body fluids contain too much acid which can affect the pH of the blood.

The severity of DKA is categorised by the degree of acidosis:

- mild pH<7.3

- moderate pH< 7.2

- severe pH<7.1

In New Zealand the normal range for blood pH is 7.35 – 7.45.

Kussmaul Respiration

Kussmaul respiration is a deep and laboured breathing pattern that is seen when the body or organs have become too acidic.[4]

Extra ketones in the body cause acid to build up in the blood, causing higher rates of breathing.

Faster breathing expels more carbon dioxide

In some cases the person who has become acidotic exhibits a fruity breath odour as a result of acetone, which is one of the acids created in the ketosis.

Dehydration

Dehydration, hypotension (low blood pressure), tachycardia (fast heart rate) are all common in the person with DKA.[5]

Dehydration results from the osmotic diuresis due to the hyperglycemia. Osmotic diuresis is a condition where the body loses too much water and electrolytes.

This then results in water and electrolyte loss such as:

- sodium

- potassium

- magnesium

- phosphate

- chloride

- calcium

Gastrointestinal symptoms

If the person with DKA is experiencing nausea and vomiting, this then further worsens the loss of fluids.

Gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, and though not yet fully understood, it is believed that electrolyte disturbances and metabolic acidosis are the cause.[6]

The successful management of DKA treatment requires correction of dehydration, hyperglycemia and electrolyte imbalances.

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia or low blood sugar is a lowered plasma glucose level. It is also a major obstacle to maintaining glycemic control for many patients related to its fear associated with hypoglycemia.

When blood sugar goes below 4mmol/l that is classified as low.

The three levels of hypoglycemia are:

- mild (3.4 – 4mmol/l)

- moderate (2.9 – 3mmol/l)

- severe (2.9 mmol/l and below)

The brain is one of the first organs affected by a lowered blood sugar as it is unable to synthesise or store this primary source of energy.[7]

Hypoglycemia can be caused by:

- missing or delaying a meal

- eating less food than planned

- vigorous exercise without carbohydrate compensation

- taking too much insulin

- drinking alcohol

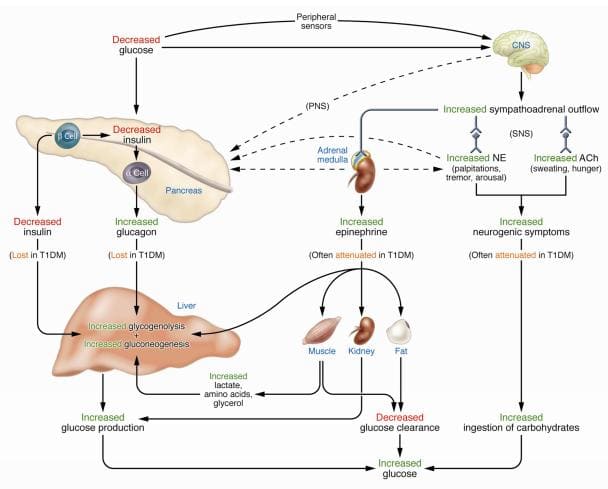

The symptoms of hypoglycemia are divided into two categories, neurogenic and neuroglycopenic symptoms.

Neurogenic symptoms are activated by the autonomic nervous system which is responsible for regulating many of the body’s involuntary functions, including the release of hormones in response to hypoglycemia.

Neurogenic symptoms include:

- shakiness

- trembling

- anxiety

- nervousness

- increased heart rate

- clamminess

- sweating

- dry mouth

- hunger sensation

- pupil dilation

- pallor

Neuroglycopenic symptoms (neuronal dysfunction due to shortage of glucose in the brain) include:

- irritability

- confusion

- ataxia (loss of coordination)

- difficulty in speaking

- headaches

- stupor

- paraesthesia (pins and needle sensation)[8]

Source: Cryer PE. Mechanisms of sympathoadrenal failure and hypoglycemia in diabetes. (2006)

Mild hypoglycemia (3.4 – 4 mmol/l) is mostly self-recognised and self-treated. Autonomic or neurogenic symptoms are triggered by the falling blood sugar. These symptoms include:

- trembling

- palpitations

- sweating

- shakiness

- anxiety

- hunger

Moderate hypoglycemia (2.9 – 3 mmol/l) involves neurogenic and neuroglycopenic symptoms. The person who has developed a moderate hypoglycemic level is usually conscious and still able to self-treat.

The neuroglycopenic symptoms occur as a result of the brain being deprived of glucose and this is often seen as:

- confusion

- difficulty concentrating

- weakness

- blurred vision

- dizziness

- difficulty speaking

Severe hypoglycemia (less than 2.9 mmol/l) is associated with confusion, convulsions or unconsciousness. Brain dysfunction starts at a level of 2.8 mmol/l, with the risk of lapsing into a coma if treatment is not initiated quickly enough.

A severe hypoglycemic event requires assistance from others to reverse and is often a medical emergency requiring hospitalisation.

Severe hypoglycemia can result in a coma

Treatment for severe hypoglycemia is most often intravenous glucose.

Short term risks of hypoglycemia include potentially dangerous circumstances that may arise when someone is hypoglycemic while, for example, driving.

Long-term consequences of hypoglycemia include mild cognitive impairment.

For the person who has type 1 diabetes ongoing education and review of their management of hypoglycemia is crucial to aid with minimising and preventing hypoglycemic events from occurring.

Related Questions

1. At what sugar level does diabetic coma occur?

The onset of brain dysfunction and developing coma is around 2.8 mmol/l and below.

2. How can I quickly lower blood sugar levels?

Taking extra insulin plus an increase in exercise or activity will lower blood sugars quickly.

3. Does intermittent fasting help with managing type 1 diabetes?

Current studies on the safety and benefits of intermittent fasting with diabetes are very limited.

Intermittent fasting is generally not recommended for the person with type 1 diabetes as it may affect their glucose levels and insulin needs significantly.

If you have type 1 diabetes and would like to give intermittent fasting a try, you should consult with your healthcare provider to work together to ensure your safety.[9]

RELATED — Intermittent Fasting: Diet with actual health benefits

Joyce has been nursing since the 1980s, and for the past 20 years she has been focusing on patients with diabetes.

Given that diabetes can be a debilitating disease if not managed properly, Joyce’s focus is to ensure that individuals with diabetes have all the correct information. She works diligently and her focus is to prepare, inform and make sure that the individuals are well equipped with knowledge and support to live with the disease 24 hours a day.

References

(1) McCance, K., Huether, S., Brashers, V., Rote, N. McCance & Huether’s Pathophysiology, 9th Edition. (2010)

(2) Bereda, G. Diabetic Ketoacidosis: Precipitating Factors, Pathophysiology, and Management. Biomedical Journal of Scientific and Technical Research. (2022). Retrieved from https://biomedres.us/pdfs/BJSTR.MS.ID.007105.pdf

(3) Fowler, M. Hyperglycemic Crisis in Adults: Pathophysiology, Presentation, Pitfalls, and Prevention. Clinical Diabetes. (2009). Retrieved from

(4) Koul, P. Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Current Appraisal of Pathophysiology and Management. Clinical Pediatrics. (2008)

(5) Aramovna, D., Obloqulov, J., Norova, E., Xudoyberdiyev, B. Diabetic Ketoacidosis, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Central Asian Journal of Medical and Natural Sciences. (2023)

(6) Hyperglycemic Crises in Diabetes. American Diabetes Association. (2004). Retrieved from https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/27/suppl_1/s94/24631/Hyperglycemic-Crises-in-Diabetes

(7) Briscoe, V., Davis, S. Hypoglycemia in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Management. Clinical Diabetes. (2006). Retrieved from https://diabetesjournals.org/clinical/article/24/3/115/1576/Hypoglycemia-in-Type-1-and-Type-2-Diabetes

(8) Cryer, P. Hypoglycemia in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. (2010)

(9) Grajower, M., Horne, B. Clinical Management of Intermittent Fasting in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6521152/