Aysegul Aktalay

(Registered Counsellor NZAC, MCouns, Psychology BSc, EMDR Therapist)

Depression is a widespread mental health condition that affects millions of individuals worldwide. It is characterised by persistent feelings of

- sadness

- hopelessness

- loss of interest or pleasure in activities

Symptoms of depression can vary widely, but common signs include changes in appetite, sleep disturbances, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating.

Early recognition of these symptoms is crucial, as they can serve as vital indicators for the need for intervention and support.

Appetite

Appetite changes in depression can vary among individuals, with some experiencing increased appetite and weight gain, while others may have a reduced appetite and weight loss.

These are often accompanied by changes in eating habits, such as overeating or undereating, which can further impact weight and overall health.

RELATED — The Healthy Plate Model: Essentials of Healthy Eating

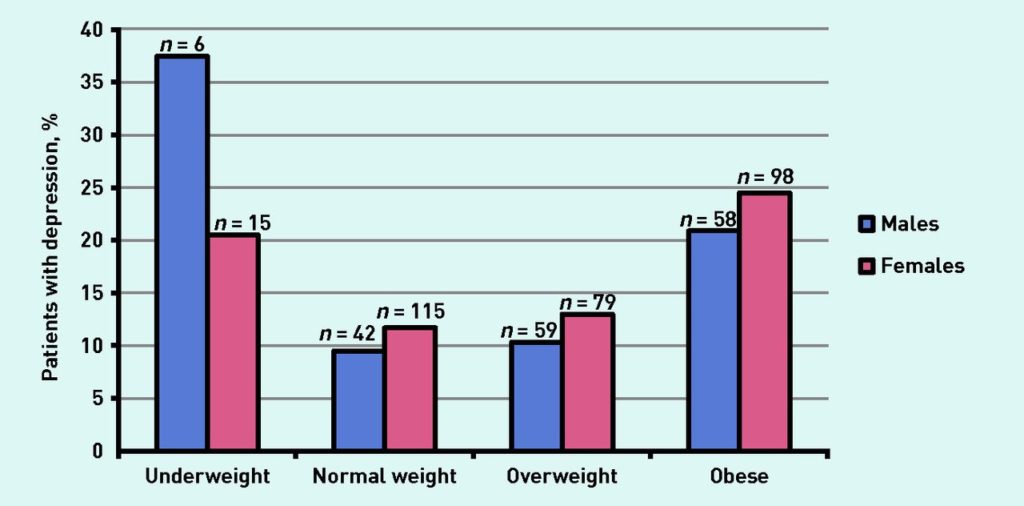

Simon et al. (2006) investigated the association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population and this study suggests that individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher consistently exhibit higher lifetime prevalence rates of mood and anxiety disorders compared to those with a BMI below 30.[1]

Source: Carey, Mariko. Prevalence of comorbid depression and obesity in general practice: a cross-sectional survey. (2014)

In conclusion, appetite changes in depression are highly individualised, leading to either increased or reduced appetite, which can affect eating habits and, consequently, weight and overall health.

Research, such as that by Simon et al. (2006), indicates a strong link between obesity and mood or anxiety disorders, highlighting the importance of addressing these issues comprehensively in clinical practice.[1]

Chronic physical pain

Chronic physical pain, a condition affecting millions worldwide, is deeply intertwined with mental health, particularly depression.

The relationship between chronic pain and depression is complex, with each often exacerbating the other. Individuals experiencing chronic pain may be more likely to develop depression, and those with depression may be more sensitive to pain.

Individuals with chronic pain may be more likely to develop depression

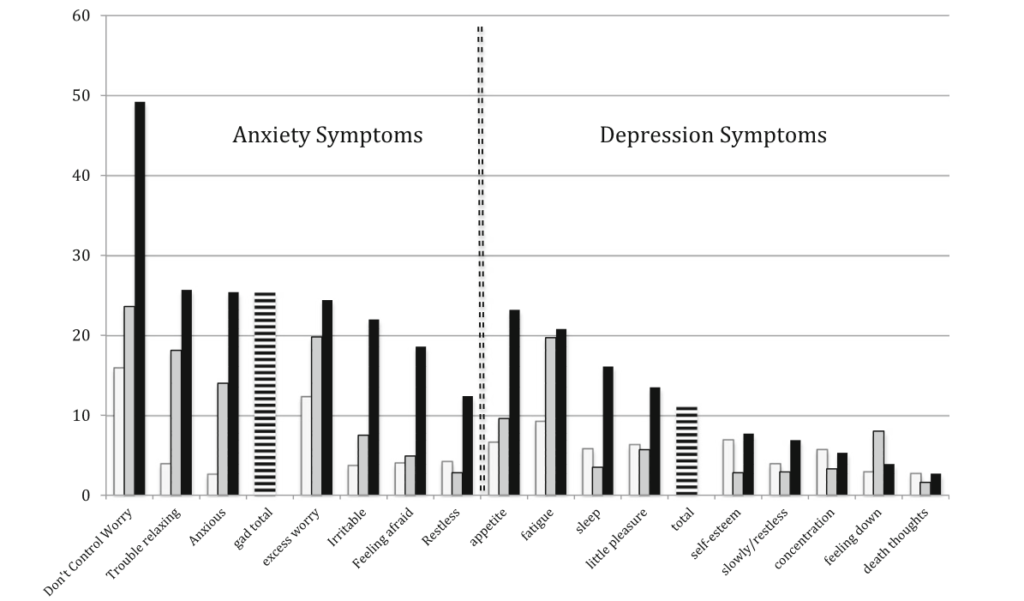

A study from 2017 on 782 patients found that anxiety symptoms were more strongly associated with migraine risk than depression symptoms.[2]

Specific anxiety symptoms like inability to control worrying and trouble relaxing showed the highest odds ratios for migraine.

Physical symptoms of depression such as appetite changes, fatigue, and poor sleep were more linked to migraine than emotional symptoms.[2]

Crying

Crying frequently can indicate underlying emotional distress or be a symptom of various mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety disorders, or adjustment disorders.

Studies suggest that crying is a natural and beneficial emotional response, aiding individuals in coping with stress and emotional pain.[3]

Crying aids certain individuals to cope with stress

Vingerhoets and Bylsma (2007) explored the psychological and physiological effects of crying, its function as a coping mechanism, and its possible indication of compromised health.[4]

Their findings suggested limited empirical evidence supporting the notion that crying provides relief or that suppressing tears is harmful to health.

Contrary to expectations, depressed individuals were not more prone to crying than nondepressed individuals when exposed to a standardised cry-inducing stimulus.

Nondepressed individuals who did cry exhibited greater sadness and physiological arousal than depressed individuals, indicating differences in emotional regulation between the two groups.[5]

Difficulty to concentrate

Difficulty concentrating is a common symptom of major depressive disorder (MDD) that can significantly impact daily functioning.

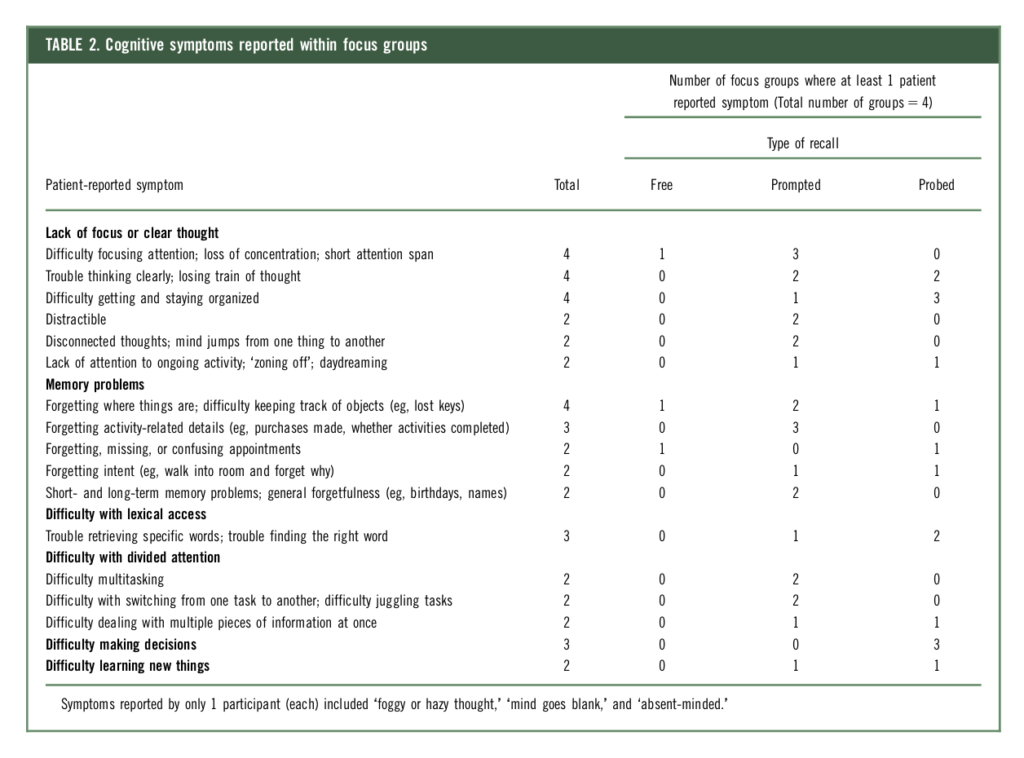

In a 2016 study on cognitive symptoms in patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), researchers found that difficulties with concentration, memory, and decision-making were common.[6]

Other notable cognitive symptoms included trouble thinking clearly and disorganisation.

Additionally, McDermott and Ebmeier (2009) conducted a meta-analysis focusing on the relationship between depression severity and cognitive function. The average severity of depression, as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17), ranged from 18.5 in studies related to semantic memory to 24.9 in studies focusing on episodic memory.[7]

They found significant correlations between depression severity and performance in episodic memory, executive function, and processing speed.

This suggests that cognitive impairment, including difficulties with concentration, may be linked to the severity of depression.[7]

Drinking

Alcohol consumption is often considered a risk factor for both anxiety and depression.

Boden and Fergusson (2011) reviewed the literature on the relationship between alcohol use disorders (AUD) and major depression (MD) to assess the existence of a causal relationship.[8]

The study found that having either alcohol use disorder (AUD) or major depression (MD) doubled the risk of developing the other, indicating a likely cause-and-effect relationship. It is more likely that AUD increases the risk of MD, rather than the other way around.[8]

Alcohol use may double the risk of developing a mental disorder

This could be due to changes in the brain and body caused by alcohol exposure, affecting how the brain works and how the body processes substances.

Irritability

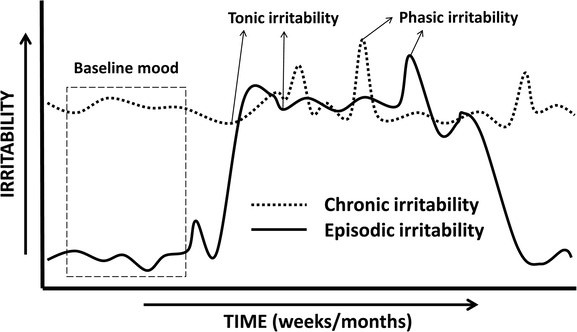

Irritability, a diagnostic symptom of child-adolescent but not adult MDD in current diagnostic systems, was assessed as a criterion for adult MDD in the study.

The researchers found that irritability during depressive episodes was reported by approximately half of respondents with lifetime MDD, but irritability in the absence of either sad mood or loss of interest was rare.[9]

Source: Vidal-Ribas., Pablo. How and Why Are Irritability and Depression Linked? (2020)

The symptom profiles for the nine DSM-IV Criterion A symptoms in the worst lifetime episode are mostly similar between individuals with irritable and non-irritable major depressive disorder (MDD).

However, fatigue and self-reproach were significantly more common in irritable MDD compared to non-irritable MDD.[9]

Feeling of emptiness

Emptiness is often regarded as a significant indicator of depression, reflecting the profound emotional and psychological experiences individuals may endure.

Studies such as Rhodas et al. (2019) highlight the profound impact of long-term depression on individuals’ lives. The study includes four women and three men who had experienced depression for a minimum of four years.[10]

The participants described a profound sense of emptiness that:

- encompassed a decline in will

- disconnection from others

- bleak outlook on the future

- emotional numbness

- feeling of being engulfed by despair

These findings underscore the depth of emptiness as a prevalent and poignant manifestation of depression, highlighting the complex and debilitating nature of this mental health condition.[10]

Related Questions

1. Is depression caused by a chemical imbalance?

The exact cause of depression is complex and not fully understood, but it’s believed to involve a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors, including potential chemical imbalances in the brain.

2. What percentage of depression is genetic?

Meta-analyses, such as Sullivan et al. (2000) estimate major depression’s heritability, often finding genetic factors contribute significantly (30-50% or higher).[11]

3. Is there a depression rating scale?

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are among the most used depression rating scales in clinical practice and research.

If you would like to know more about depression, we suggest reading Introduction to: Depression.

Aysegul is a full member and a registered counsellor for New Zealand Association of Counsellors and is also a member of EMDRNZ (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing New Zealand). She has more than ten years of experience as a counselling psychologist overseas, which today serves as a foundation for her in-depth clinical skills…

If you would like to learn more about Aysegul, see Expert: Aysegul Aktalay.

References

(1) Simon, G. E., Von Korff, M., Saunders, K., Miglioretti, D. L., Crane, P. K., Van Belle, G., & Kessler, R. C. (2006). Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 824-830. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/article-abstract/209790

(2) Prieto Peres, M. F., Mercante, J. P. P., Tobo, P. R., Kamei, H., & Bigal, M. E. (2017). Anxiety and depression symptoms and migraine: A symptom-based approach research. The Journal of Headache and Pain. Retrieved from https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s10194-017-0742-1

(3) Bylsma, L. M., Vingerhoets, A. J., & Rottenberg, J. (2008). When is crying cathartic? An international study. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(10), 1165-1187.

(4) Vingerhoets, A., & Bylsma, L. (2007). Crying as a multifaceted health psychology conceptualization: Crying as coping, risk factor, and symptom. The European Health Psychologist, 9, 76-82. Retrieved from https://ehps.net/ehp/index.php/contents/article/view/ehp.v9.i4.p68/929

(5) Rottenberg, J., Gross, J. J., Wilhelm, F. H., Najmi, S., & Gotlib, I. H. (2002). Crying threshold and intensity in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(2), 302–312.

(6) Fehnel, S. E., Forsyth, B. H., DiBenedetti, D. B., Danchenko, N., François, C., & Brevig, T. (2016). Patient-centered assessment of cognitive symptoms of depression. CNS Spectrums, 21, 43–52. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257073778_Patient-centered_assessment_of_cognitive_symptoms_of_depression

(7) McDermott, L. M., & Ebmeier, K. P. (2009). A meta-analysis of depression severity and cognitive function. Journal of Affective Disorders, 119, 1–8.

(8) Boden, J. M., & Fergusson, D. M. (2011). Alcohol and depression. Christchurch Health and Development Study. University of Otago, Christchurch School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

(9) Fava, M., Hwang, I., Rush, A. J., Sampson, N., Walters, E. E., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). The importance of irritability as a symptom of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(8), 856–867.

(10) Rhodes, J., Hackney, S., & Smith, J. A. (2019). Emptiness, engulfment, and life struggle: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of chronic depression. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 32(4), 390-407.

(11) Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(10), 1552. Retrieved from https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552