Carly Hanna

BSc (Human Nutrition and Psychology)

Before continuing with this article, we suggest reading the first part in the series – How Binge Eating affects our mental and physical health (Part 1).

In this article we will discuss how binge eating can in the long term affect our

- liver and kidney health

- nutrition

- emotional state

and how individuals with a binge eating disorder are more likely to have comorbid anxiety, depression and a higher risk of suicide.

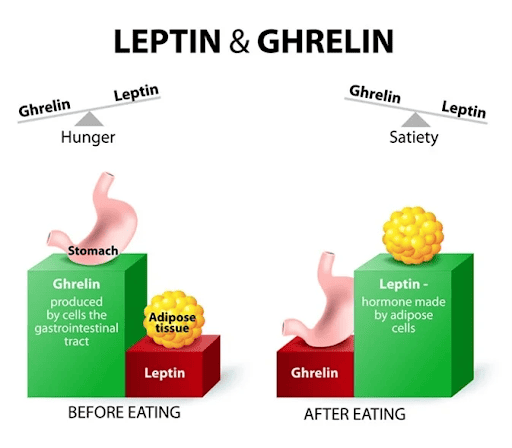

Binge eating negatively affects hunger and fullness cues

With binge eating disorder, it can be hard to recognise the body’s hunger and satiety cues.

Ghrelin is the hormone produced by the gut that signals to the brain that we are hungry. It is also known as the hunger hormone.

Leptin, on the other hand, is a hormone produced by the fat cells that signals to the brain that we are full and should stop eating. It is also known as the satiety hormone.[1]

When ghrelin and leptin signals are ignored, such as when someone is full but continues eating anyway, this means that our hunger and satiety cues are dysregulated.

This makes it hard for the brain and body to decide when it is hungry, to initiate eating, and when it is full to stop eating.[2]

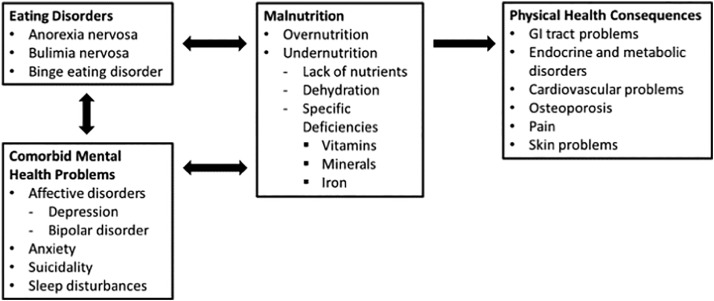

Binge eating can cause malnutrition

Malnutrition can include overnutrition (obesity) or undernutrition (nutrient deficiencies and/or dehydration).

The types of foods that people are most likely to binge eat are energy dense and nutrient poor.

This increases the likelihood of gaining weight, as well as increasing the risk of having several vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

Processed foods are most likely to be consumed in binge eating episodes

Binge eating can adversely affect kidneys and liver

Diabetes, heart disease and hypertension (high blood pressure) are all risk factors for kidney disease and can all be complications as a result of long-term binge eating disorder.

RELATED — Type 1 Diabetes: Autoimmune disease that is on the rise

Kidney disease can also develop as a result of dehydration, calorie restriction or purging, which are also associated with eating disorders such as binge eating.

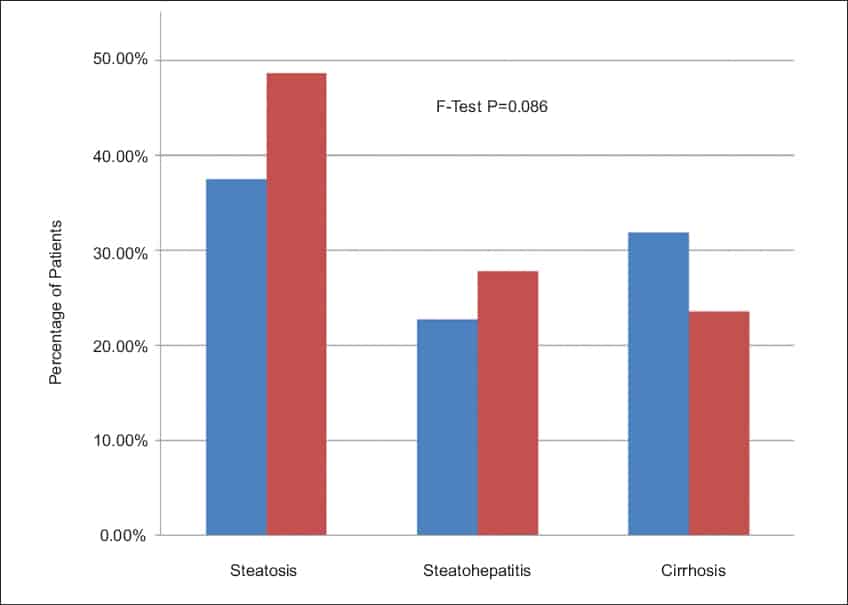

As for our liver health, up to 85% of those with a binge eating disorder develop fatty liver disease.[5]

Source: Zhang, J. Pilot study of the prevalence of binge eating disorder in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. (2017)

This can be a result of having a high BMI and/or adipose tissue surrounding the organs. However, this can be reversed if regular eating patterns are resumed.

Binge eating and tiredness

It takes a lot of energy to digest large amounts of food in one sitting. That is why after binge eating you can feel very sluggish and tired.

Binge eating can cause a wide range of symptoms, such as:

- fatigue

- brain fog

- poor concentration

- sluggishness

Having such feelings often starts to affect both physical and mental health.

Binge eating increases emotional dysregulation

Binge eating can be associated with body image issues, such as body dysmorphia.

Body dysmorphia is a condition where one perceives their appearance differently to what it actually is.

However, in most cases, binge eating is a result of poor emotional regulation. For some, binge eating can be a way of coping with uncomfortable emotions. This can become a vicious cycle when binge eating itself then reinforces feelings of shame, guilt and hopelessness.

This then increases the risk of mental health comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression.

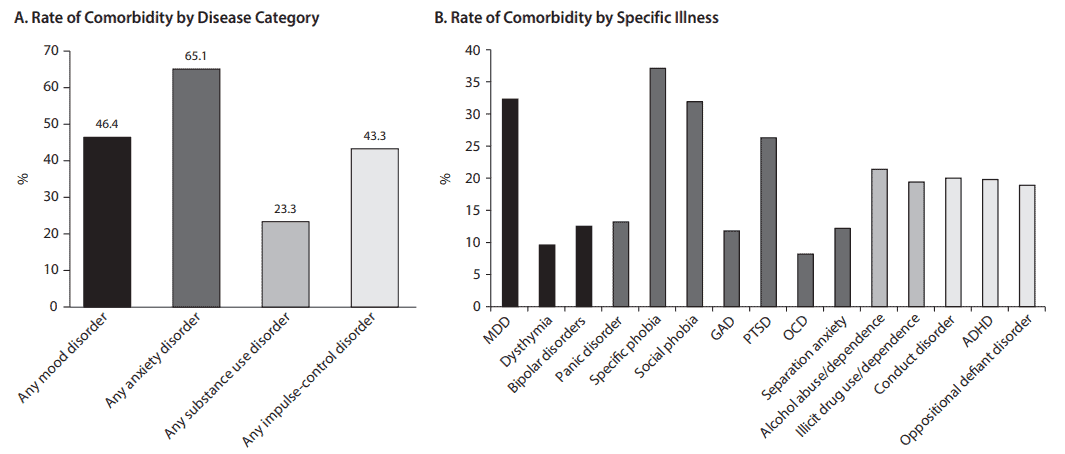

Anxiety levels and binge eating

Some of the characteristics of binge eating include eating alone or feelings of embarrassment and shame when eating around others. This can cause social anxiety, especially when food is such an important part of people’s culture and social gatherings.[6]

Binge eating heightens anxiety

Being unable to control one’s eating habits can cause a lot of stress and anxiety for an individual.

Source: Citrome, L. Binge-Eating Disorder and Comorbid Conditions: Differential Diagnosis and Implications for Treatment. (2017)

Not only can binge eating disorder be a result of underlying anxiety, but binge eating disorder can also be a precipitating factor of an anxiety disorder.

Binge eating increases social isolation and depression

As a result of binge eating behaviour, people may isolate themselves in fear and shame of being around others when they are eating. Along with feelings of hopelessness, guilt and apathy, this can lead to depression.

Comorbid binge eating disorder and depression can cause a cyclic trend of binge eating in order to deal with low mood and end up having negative emotions as a result of the binge eating.[6,7]

This is why social support is such an important factor in binge eating treatment, which will be discussed in future articles.

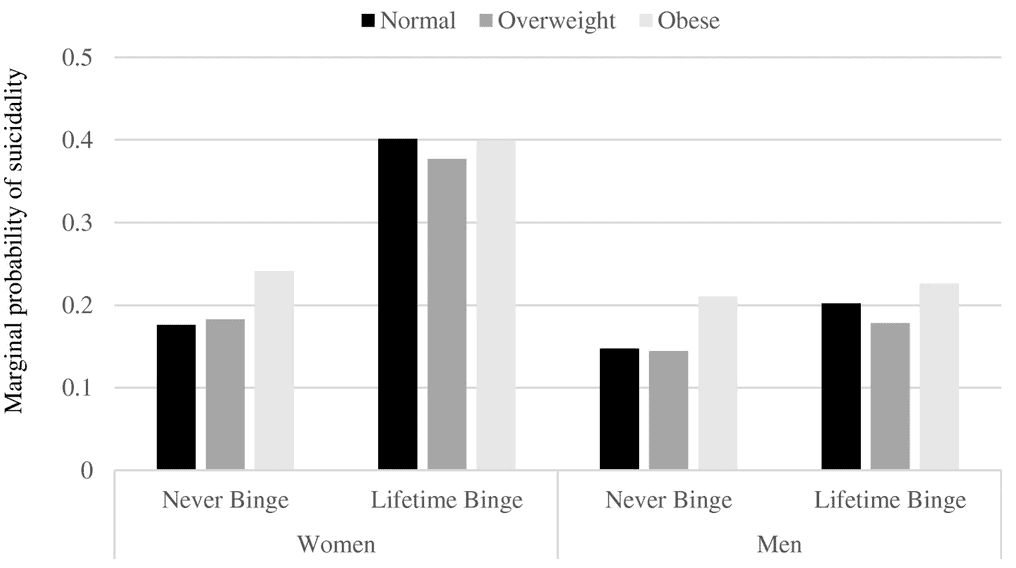

Binge eating increases the risk of suicide

Having an eating disorder, such as binge eating disorder, can be a risk factor for suicide attempts, especially if there is comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety and/or depression.[8]

Some research has shown that those with a history of binge eating have a higher marginal probability of suicide, compared to those who have never engaged in binge eating.

While there are several factors that contribute to suicide risk, the good news is that mental health comorbidities can be reduced/avoided if binge eating is treated.[9]

There are several self-help tips to manage binge eating; this information will come in a future article.

In the meantime, if you are concerned for your own safety, or the welfare of someone else, please reach out for support:

Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time for support from a trained counsellor.

Lifeline – 0800 543 354 (0800 LIFELINE) or free text 4357 (HELP).

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234 or email talk@youthline.co.nz or online chat.

Samaritans – 0800 726 666

Suicide Crisis Helpline – 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO).

Healthline – 0800 611 116

Depression Helpline – 0800 111 757 or free text 4202 (to talk to a trained counsellor about how you are feeling or to ask any questions).

Related Questions

1. Can eating ultra-processed foods (NOVA-3 and NOVA-4) exacerbate binge eating disorder?

Studies have shown that ultra-processed foods (NOVA-3 and NOVA-4) can drive overconsumption and contribute to binge eating.[10]

2. Can binge eating cause heart palpitations?

Periods of starvation are more likely to cause heart palpitations, however, binge eating can cause symptoms of heartburn and indigestion which can often be misconceived as heart palpitations.

3. Is binge eating more serious than bulimia nervosa?

Binge eating is serious when risks of health conditions increase due to being overweight or obese.

Bulimia nervosa can be more serious than binge eating due to purging behaviours, which carry their own health risks.

Having passion for mental health and nutrition, Carly’s goal is to become a registered psychologist with a focus on self-care – food, exercise, and sleep. She has a special interest in various mental health disorders, plant-based diets, and the relationship between food and mood.

Through evidence-based research, holistic approach to health and personal experience, Carly hopes to empower others’ well-being.

Carly is a part of the Content Team that brings you the latest research at D’Connect.

References

(1) Liji Thomas. Ghrelin and Leptin. News Medical. 2021 Feb 17. Accessed online. Retrieved from https://www.news-medical.net/health/Ghrelin-and-Leptin.aspx

(2) National Eating Disorder Association. Health consequences. 2022. Accessed online, retrieved from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/health-consequences

(3) Scribner C. Understanding nutritional needs of patients with eating disorders: implications for psychiatrists. Psychiatric Times. 2016;33(4). Retrieved from https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/understanding-nutritional-needs-patients-eating-disorders-implications-psychiatrists

(4) Himmerich H, Kan C, Au K, Treasure J. Pharmacological treatment of eating disorders, comorbid mental health problems, malnutrition and physical health consequences. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2021 Jan 1;217:107667. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107667

(5) Robert Rister. 4 things you should know about liver damage and eating disorders. Steady Health. 2019 Feb 11. Accessed online. Retrieved from https://www.steadyhealth.com/articles/4-things-you-should-know-about-liver-damage-and-eating-disorders

(6) The Emily Program. Physical effects of binge eating disorder. Jan 31 2022. Accessed online, retrieved from https://www.emilyprogram.com/blog/physical-effects-of-binge-eating-disorder/

(7) Stephnia Watson. Serious health problems caused by binge eating disorder. WebMD. Oct 20 2021. Accessed online, retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/binge-eating-disorder/health-problems-binge-eating

(8) Submission to the New Zealand Government Mental Health Inquiry. Jun 2018. Retrieved from https://www.ed.org.nz/files/EDANZ_Submission_to_Mental_Health_Inquiry.pdf

(9) Brown, K.L., LaRose, J.G. & Mezuk, B. The relationship between body mass index, binge eating disorder and suicidality. BMC Psychiatry 18, 196 (2018). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1766-z

(10) Ayton A, Ibrahim A, Dugan J, Galvin E, Wright OW. Ultra-processed foods and binge eating: A retrospective observational study. Nutrition. 2021;84:111023. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.111023 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33153827/